The determinants of obesity are multifaceted and complex( Reference Huang, Drewnowski and Kumanyika 1 ). Explanations for the causes of and solutions to obesity are political, social and highly debated; the framing of this issue varies across stakeholders( Reference Kwan 2 ). Framing has been defined as ‘the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue’( Reference Chong and Druckman 3 ). Framing involves the selection, salience or omission of certain information, and includes values and moral judgements( Reference Entman 4 – Reference Lawrence 7 ). Importantly, frames can help shape perceptions and parameters of health issues among the public and policy makers, ultimately influencing policy development and enactment( Reference Kwan 2 , Reference Chong and Druckman 3 , Reference Gollust, Niederdeppe and Barry 8 ). The reframing of tobacco from an individual problem to a public one that held the tobacco industry accountable is one example of an effective use of framing( Reference Nathanson 9 , Reference Smith, Dorfman and Freudenberg 10 ). Many other public health examples illustrate the influence framing can have on public opinion and policy( Reference Siegel and Lotenberg 11 ).

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) proposed regulations for nutrition labelling provide a timely opportunity to understand message framing as it relates to obesity prevention. Much research on the framing of obesity has focused on analysis of news and media accounts( Reference Lawrence 7 , Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne 12 – Reference Ryan 17 ). A growing body of research has documented a ‘public health’ frame for obesity, typically focused on systemic forces that contribute to obesity (e.g. the obesogenic environment characterized by the accessibility of low-cost, energy-dense foods; industry marketing practices) and preventive and structural approaches to address the issue( Reference Lawrence 7 , Reference Hawkins and Linvill 18 – Reference Pomeranz and Brownell 22 ). There has also been growing interest in understanding public health framing in the context of health policy making. As one example, Jenkin et al. analysed submissions to the 2006–2007 New Zealand Inquiry into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes( Reference Jenkin, Signal and Thomson 23 ). Their investigation revealed a prominent difference between the framing of the food/marketing industry and the public health sector in New Zealand, with industry exhibiting a more individualistic frame that put responsibility on individuals and public health exhibiting a more systemic frame that put emphasis on the role of structural factors in shaping obesity. Very little research has focused on understanding public health framing with respect to specific legislation in the context of obesity.

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated that nutrition and energy (calorie) information be provided in restaurants and other ‘similar’ food establishments. The ACA menu-labelling policy was proposed to apply to all food establishments with twenty or more locations, and was estimated to reach approximately 300000 establishments nationwide. In 2011, the FDA released the notice of proposed rulemaking for public comment (i.e. ‘notice and comment period’). The comment period is the main vehicle for participation in regulatory policy, giving the whole process a sense of democratic oversight( Reference Shapiro 24 , Reference Ellig 25 ). Federal agencies (e.g. FDA) are required to consider all comments before issuing final regulations and to provide a public record responding to the arguments raised by commenters. This process requires the FDA to support every policy decision with plausible reasoning and evidence( Reference Ellig 25 ), and recent studies have found some evidence of policy impact from public comments( Reference Shapiro 24 , Reference Yackee 26 ). We conducted a content analysis of public comments submitted in response to this policy to understand the key message framing techniques used by the private industry sector v. the public health sector in this context, with the aim of informing and improving future public health messaging, framing and advocacy.

Methods

The policy

On 6 April 2011, the FDA published a proposed rule that fulfilled the ACA nutrition-labelling mandate: ‘Food Labeling; Nutrition Labeling of Standard Menu Items in Restaurants and Similar Food Establishments’ (21 CFR Part 101). The FDA accepted written public comments on the proposed policy via Regulations.gov, the online platform for public involvement in federal regulation development. The comment period closed on 5 July 2011, after which the FDA reviewed and responded to all comments received, issuing the final regulatory action on 1 December 2014. See the online supplementary material for details about the main policy points in the proposed and final rule.

Data set

The public comments posted on Regulations.gov were used as the primary data for the current analysis. Four hundred and thirty public comment submissions to the proposed food-labelling policy were extracted from Regulations.gov on 15 December 2014, excluding submissions withheld because they contained private or proprietary information or inappropriate language, or were multiple copies of mass-mail letters. Of the 430 submissions, ninety-seven were submitted on behalf of companies, agencies and organizations from the private industry sector (n 64) or the public health sector (n 33), and were included. To be included, comments had be submitted specifically as an attached document on an organizational letterhead and signed by one or more organizational representatives. Comments from individual stakeholders not explicitly affiliated with an organization (n 285) and anonymous submissions (n 32) were excluded. Duplicate (n 11) and unrelated or inaccessible (n 5) submissions were also excluded. Submissions ranged from 1 to 28 pages, with the average length at 11·5 pages per submission. All submissions are publicly available on Regulations.gov via Docket ID FDA-2011-F-0172. For the current analysis, ‘private industry sector’ was defined as commercially operated companies involved in the manufacture or sale of foods and beverages and related trade associations. ‘Public health sector’ was operationalized as government agencies, research institutions, non-government organizations and professional organizations with a focus and/or mission related to improving health at the population level, not just the individual/clinical level. Tables 1 and 2 provide information about the data set.

Table 1 Numbers of comments included/excluded and criteria for exclusion in the data set of comments from Regulations.gov

Table 2 Numbers of comments representing private industry and public health stakeholders in the data set of comments from Regulations.gov

Analysis

A total of ninety-seven documents were coded and analysed (public health, n 33; private industry, n 64). Documents were analysed by three study investigators (R.C.S., J.C., G.L.) using an immersion and crystallization process and thematic content analysis( Reference Borkan 27 ). Analyses followed a systematic process whereby documents were independently read through by coders as text for general familiarity with content.

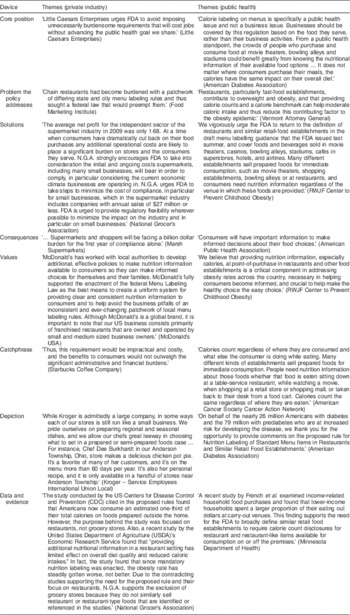

Consistent with prior frame analysis( Reference Kwan 2 ), we examined and coded the texts using a framing matrix. In a framing matrix, devices are used to convey the signature elements of a frame. The devices for the framing matrix were based on commonly identified devices that have been applied previously in the policy context( Reference Jenkin, Signal and Thomson 23 , Reference Gamson and Lasch 28 ); we refined and adapted this framing matrix to reflect our data based on pilot-testing with twelve documents from the data set (see Table 3). The broad codes that guided our analysis map on to the key devices of a frame, which included: core position, problem the policy addresses, policy solutions, policy consequences, values, data/evidence, catchphrase and depiction (see Table 3 for definitions).

Table 3 Framing matrix presenting private industry and public health frames, organized by devices and key themes

FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Texts were then subjected to systematic, line-by-line coding; and within each device, we identified key themes and illustrative quotes. Each document was analysed independently by two investigators. An iterative approach was taken in which the coding scheme remained flexible and open to accommodate the expansion of codes( Reference Van Gorp 29 , Reference Glaser and Strauss 30 ). Disagreements on coding were resolved through consensus among the investigator team. While some passages may have been coded using multiple devices based on their content, we present them in the ‘Results’ section under the device that was most salient in our analysis. Coding and analysis were facilitated by the use of Dedoose qualitative software.

Results

Key findings from the analysis are presented below and are summarized in Table 3, with themes for private industry and public health presented under each device. Illustrative quotes are also provided in Table 4.

Table 4 Framing matrix with examples of illustrative quotes from private industry and the public health sector

FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; RWJF, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Core position (overall stance on the policy issue)

Private industry

Overall, private industry perceived excessive government regulation of menu labelling to be burdensome, and argued that it should be minimal. While some large chain restaurants and businesses supported menu labelling in principle (e.g. to ‘level the playing field’) and had advocated for a national policy to help address disparate local/state labelling laws, industry consistently sought to lessen the scope and perceived ‘burden’ on businesses. They argued that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to policy implementation was not feasible or fair given the diversity of businesses affected. On the extreme end of this perspective, organizations such as entertainment complexes argued that the regulations should not apply to establishments whose primary purpose is not selling food: ‘Nobody goes to a traditional movie theater for the primary purpose of eating, which is why cinemas should be excluded under FDA’s proposed rule.’

Public health

Public health commenters virtually all supported the policy in principle and applauded the FDA’s efforts to implement a policy that seeks to provide more nutritional information to the public, facilitate healthier informed food choices among children and families, and ultimately reduce risk of obesity and other chronic diseases. Some public health commenters argued that the proposed rules should be expanded to include alcohol and retail establishments where families consume food, and expressed concern that excluding these entities would send the message that the calories consumed at these facilities ‘don’t count’.

Problem the policy addresses (why the policy is needed)

Private industry

Most of the private sector’s comments focused on the patchwork of state and local menu-labelling regulations impacting them, noting that some chain restaurants had urged Congress to pass a uniform national law to address this patchwork. A few private sector commenters acknowledged obesity and calorie overconsumption as underlying problems giving rise to regulations. Some spoke more generally about consumer health and the importance of improving consumer knowledge.

Public health

Public health commenters focused on issues related to obesity, overweight and overeating as key drivers of menu-labelling regulations. The public health sector also attributed high caloric intake to sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and the increase in meals outside the home. Public health commenters further argued that there is a lack public awareness about the caloric content of their diets. They commented on the challenging obesogenic environment as well, including the confusing lack of uniformity of calorie postings and poor access to nutritious food among low-income populations. Most public health commenters framed this as strictly a ‘public health’ issue: ‘Calorie labelling on menus is specifically a public health issue and not a business issue.’

Solutions (the solutions proposed or emphasized as a response to the issue)

Private industry

Private industry emphasized the critical role of industry self-regulation in promoting consumer health; some grocery stores and chain restaurants asserted that they were already labelling food or providing nutritional information to consumers (e.g. on websites or posters) and do not need strict oversight. A key theme among the private industry sector was the need for more flexibility and understanding in policy implementation, including how to present nutrition information in a ‘clear and conspicuous’ way, how frequently to update nutritional information and how to enforce compliance with the law. Almost all private industry interests requested that the FDA delay the time frame for implementation.

Public health

The majority of public health commenters agreed the FDA should implement the rules as proposed, although they also requested that the FDA provide additional guidance or clarification on several aspects of the regulations (e.g. font size of postings, inclusion of advertising and delivery menus, entities responsible for enforcement). Most argued to broaden the definition of covered entities to include more venues (e.g. entertainment venues, convenience stores) and to include alcoholic beverages in the regulations. A few commenters also suggested that the FDA should require posting of additional kinds of nutrition information on menus (e.g. fat and trans-fat content, sodium). Many others advocated for related additional efforts to support the policy once it is in place, including a database of covered entities, training and technical assistance for covered entities, public educational campaigns and a plan for enforcement.

Consequences (the likely consequences that will ensue from the policy)

Private industry

Private sector commenters discussed numerous logistical and operational consequences of the policy proposed, particularly for grocery stores. They argued that ‘hundreds of signs in every store will need to replace at great cost’, ‘voluminous’ record-keeping will be needed, thousands of food items will have need to have calories calculated, menus will need to be constantly updated, service will be slower, labs that provide signs and calorie testing will be overwhelmed, and substantial training will be required for employees and franchisees.

Private industry commenters also emphasized negative consequences for consumers, especially the ‘confusion’ that would result from the cluttered menus and ‘misleading’ information about the relative calorie content of different foods. Industry also cited indirect negative consequences for consumers, often providing humanizing examples (e.g. product offerings will have to be removed, robbing consumers of choices). Financial consequences were repeatedly mentioned in nearly all of the comments, with anticipation that sales would drop and cause a financial burden to both retailers and consumers. Many of the comments about the financial consequences were made by ‘small businesses’ who felt the regulations were ‘unfair and unjustified’. Several organizations felt that ‘the rule will drastically curtail an entrepreneurial culture that exists’ and would do so disproportionately within industry. Many of the private industry commenters were concerned about the potential negative legal consequences of the regulations, such as fines for non-compliance or conflicts with existing local and state laws.

Public health

Public commenters focused almost exclusively on the positive consequences of implementing the menu-labelling policy, including honouring Congressional intent and providing consumers the caloric information they need and want to make informed dietary decisions. Public health commenters also discussed potentially negative consequences of adopting a narrow interpretation of the policy or unclear nutrition labelling, including consumers’ inability to make informed choices, overconsumption, and more limited reach and impact.

Values (the core values and principles that underpin a frame)

Private industry

Many comments from private industry placed a high value on flexibility, transparency and efficiency in the language and implementation of the policy. The values of proportionality and fairness arose often: ‘this requirement would be impractical and costly, and the benefits to consumers would not outweigh the significant administrative and financial burdens’. Many argued that businesses should be protected from unnecessary financial burdens, prioritizing economic growth and cost savings. Many industries anticipated massive financial burden and job loss to implement regulations, with costs passed on to consumers. Industry valued entrepreneurship and protection of ‘small businesses community’ and family-owned businesses, particularly since the nation was facing high economic uncertainty and unemployment at the time. Finally, some private industry comments expressed their strong commitment to promoting consumer health.

Public health

Common values were justice and social responsibility related to improving population health, especially for racial/ethnic minority groups, low-income populations and children. Similarly, the prevention of chronic disease (e.g. CVD, diabetes) and promotion of public health were highly valued.

Data and evidence (the selection and presentation of data and evidence to support or rebut claims)

Private industry

Commenters often cited information about costs of compliance (unreferenced data), ineffectiveness of labelling and consumer desires/preferences (e.g. consumers do not want calorie information). Citations related to the costs included descriptive data about the types of businesses affected (e.g. size, revenue and employment) from the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) tax code. The sources they cited were diverse, numerous and tended to be non-academic, with the exception of the academic peer-reviewed studies finding no effect of labelling on consumer behaviour. Sources included consumer surveys by businesses about consumer preferences (e.g. Darden, McDonald’s, etc.), reports by federal agencies and industry trade groups, think tank studies, surveys conducted by market research firms, newspapers and dictionaries. Legal sources were also cited (e.g. court cases; texts of existing state and local laws; Obama’s Executive Order 13563 on minimizing regulatory burdens). These sources reflected industry commenters’ greater focus on regulatory and administrative complexity and the negative consequences of the policy.

Public health

The data cited by public health commenters reflected their focus on the underlying causes of obesity as the problem the policy was designed to address. They more often cited data on food consumption patterns, the role of high-calorie foods in obesity prevalence and the epidemiology of obesity. Topics included consumer spending, consumption patterns, as well as the effects and necessity of menu labelling. The topics were more academic and health-related, including the epidemiology of obesity and health-care costs related to obesity. They cited many scholarly peer-reviewed journals, textbooks and publications from public health agencies, research organizations/think tanks and federal agencies (e.g. US Department of Agriculture; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FDA).

Catchphrase (succinct and memorable words, phrases and slogans)

Private industry

The words ‘costs’ and ‘burden’ were ubiquitous. Particularly prominent was the idea of an ‘unnecessary burden’ that outweighs benefits for affected businesses. One primary ‘financial burden’ would be significant ‘job loss’ and increased costs passed on to consumers. Many highlighted the ‘impossibility’ of implementing the proposed policy, including the steep learning curve and significant resources involved in policy implementation. The phrase ‘common sense’ was also repeated, in relation to the need for the FDA to take a less restrictive, more flexible approach when determining the extent of the regulations.

Public health

Public health catchphrases were predominantly health-related. One common catchphrase was ‘all calories count’ and ‘calories count the same’, regardless of the setting or where they are consumed. Other repeated phrases related to ‘informed choices’ and ‘healthy choices’ about consumed foods and beverages, and obesity as a ‘devastating public health epidemic’.

Depiction (characterization of themselves and their opponents)

Private industry

Many private industries depicted themselves as supporting the goal of healthy, educated consumers; in effect, they agreed with the FDA on the goals, but not necessarily the means. Many grocery stores, restaurants (e.g. Panera, Starbucks, McDonald’s) and associations (e.g. American Beverage Association) emphasized that they were already providing nutrition information to their customers and historically have been leaders in menu labelling. Many depicted themselves in personal terms, not as large corporations but a collection of small businesses, families or individuals.

Many portrayed themselves as vulnerable businesses that could not handle the additional costs.

Public health

Health-related non-governmental organizations highlighted their large constituencies that represented many health professionals and consumers. They reported on protecting the health of Americans, particularly vulnerable populations (e.g. low-income, minority, children, diabetic).

Discussion

The present paper sought to understand how national menu-labelling legislation is framed by public health and private industry sectors through the forum of public comments. Although we found some similarities between the public health and industry frames (i.e. a strong focus on consumers and consumer health, agreement on need for more clarification of the law and some overlap in the data and sources cited), we identified marked differences in the frames used by public health and private industry. These frames often mirrored frequently competing frames of market justice v. social justice that have been identified in prior literature( Reference Dorfman, Wallack and Woodruff 31 , Reference Beauchamp 32 ). Market justice framing is oriented towards values of self-determination, limited obligation to the collective good and limited government intervention( Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne 12 , Reference Dorfman, Wallack and Woodruff 31 , Reference Beauchamp 32 ). Social justice framing iterates shared responsibility, strong obligation to the collective good and cooperation( Reference Dorfman, Wallack and Woodruff 31 , Reference Beauchamp 32 ).

Industry has been a powerful force that shapes the frames that influence obesity policy( Reference Freudenberg 33 ). Prior research has also demonstrated the impressive ability of food companies to organize and advocate through trade associations – effectively engaging in lobbying and public relations to exercise political influence( Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne 12 , Reference Gupta and Brubaker 34 , Reference Spillman 35 ). While our analysis adds rich detail in the context of a specific national obesity prevention policy, the industry frame we identified was similar to the market justice frame identified in prior studies( Reference Kwan 2 , Reference Jenkin, Signal and Thomson 23 , Reference Roberto and Pomeranz 36 , Reference Donaldson, Cohen and Truant 37 ). Across private industry, there was uniformity about the importance of minimizing government regulation and the need for the least burdensome, most flexible methods of compliance with the regulations. Industry focused on the negative consequences of the policy and the critical importance of flexibility to reduce the burden of compliance. Industry used emotional appeals and often took a humanizing perspective in its discussion of consequences, and all solutions were geared towards minimizing costs and logistical burdens. Most private sector interests focused on communicating values and consistently depicted themselves as a ‘vulnerable’ collection of small, family-run businesses that supported healthy and informed consumers. Consistent with prior content analyses( Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne 12 , Reference Roberto and Pomeranz 36 ), many private sector restaurants congratulated themselves on advancing public health through current policies and many advocated for voluntary self-regulation related to menu labelling. This is consistent with a recent content analysis of the food and beverage industry’s framing of obesity in the news, which identified a shift in recent years away from framing obesity as an issue of personal responsibility and towards the message that the food and beverage industry wants to be ‘part of the solution’( Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne 12 ). Public health should be wary of industry claims of self-regulation, as research suggests that these self-regulatory programmes have not been very impactful( Reference Powell, Harris and Fox 38 , Reference Castonguay, Kunkel and Wright 39 ). Furthermore, some of the arguments made against the policy on behalf of industry (e.g. too much regulation, will hurt businesses and especially small businesses, industry already taking steps to make consumers healthy) mirror those found in a content analysis that identified arguments made against the sugar-sweetened beverage portion limit policy( Reference Roberto and Pomeranz 36 ).

Our research identified a unified public health frame that was supportive of the menu-labelling policy. Public health commenters largely took a social justice perspective( Reference Jenkin, Signal and Thomson 23 ), focusing on the critical importance of protecting the public’s health, identifying specific vulnerable groups that are affected and emphasizing the positive consequences of the law. While the public health framing was unified, there are several critiques and potential opportunities for improving messaging. Most saliently, the public health sector tended not to address the common arguments presented by industry, particularly in terms of the impact and cost burden that the regulations will have on industry. As such, public health may have been unnecessarily narrow in its framing and not explicit enough about the role of industry in contributing to an obesogenic environment. Furthermore, the public health sector did not take full advantage of many of the framing devices including metaphors, humanizing techniques or anecdotes that may enhance the emotional appeal of its argument. Public health commenters should consider integrating such devices to make their case stronger and more salient( Reference Shapiro 24 – Reference Yackee 26 ).

The current research is useful in anticipating opposition frames and addressing the common tension between individual choice and market freedom v. protection of public health by government. Public health should be more prepared to address this tension and consider some of the lessons learned from some of the denormalization strategies that have been successful for tobacco( Reference Leatherdale, Sparks and Kirsh 40 ). This may require messaging that more explicitly makes corporations responsible for their actions and highlights the industry’s use of social responsibility programmes as disingenuous, as has been done in the context of tobacco( Reference Leatherdale, Sparks and Kirsh 40 , Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman 41 ). While some argue that public health would benefit from rooting its language and framing in values more strongly in a social justice framework( Reference Dorfman, Wallack and Woodruff 31 , Reference Lakoff 42 ), others argue that the language of collectivity is less compelling in US political discourse. This perspective asserts that the market justice frame presented by industry is more dominant in the USA( Reference Dorfman, Wallack and Woodruff 31 , Reference Wallack and Lawrence 43 ). It is not clear what the right balance between social justice and market justice framing should be in public health messaging in the obesity policy context. One recent study suggests it may be advisable for public health advocates to incorporate messages about personal responsibility into their framing, since several studies suggest that failure to recognize individual responsibility in narratives about the social determinants of obesity may undermine the persuasion of policy narratives( Reference Niederdeppe, Roh and Shapiro 44 ). Other studies suggest that messages that do not present both sides of a message (e.g. articulates a position and refutes opposing arguments) may face greater opposition( Reference Aday 45 ). More research is needed to better understand the impact of market justice v. social justice framing on behalf of public health advocates in the context of specific obesity prevention policies.

Limitations of the study should be acknowledged. Public health and industry framing may be different in this context from framing in the media or during legislative testimony or debate, or around a different proposed policy solution. Furthermore, our analysis focused on a relatively small sample size and concerns only a selection of the regulatory debate, as we did not have access to comments that were not available through the public data set from the FDA, and those comments may have used different framing from the comments we analysed. We also chose to exclude individual commenters because it was not possible to connect them with a specific sector (public health or industry), but recognize it is possible that individuals making comments could have also represented private industry or public health perspectives. However, this data set of voluntary, public submissions yielded a range of views and rhetoric representing the interests of a diverse array of stakeholders( Reference Jenkin, Signal and Thomson 23 , Reference Wilkinson 46 ). We acknowledge that there are limitations of a consensus approach, including the limited generalizability of our findings( Reference Hussein, Hirst and Salyers 47 ). Finally, we were not able to make any causal claims about how the framing of these issues by either sector influenced policy makers in determining the final rule, and future research should explicitly test the effectiveness of some of the framing techniques suggested here.

Following the industry and public health commentaries, the final regulations were released on 1 December 2014. The final rule was even stronger than the proposed regulation and considered a public health success( Reference Goldman 48 ). However, the FDA has agreed to delay required implementation of the policy until 5 May 2017, to allow businesses sufficient time to comply with the regulations, and the details of enforcement are still unclear. Given that recent bills have come up through the House to repeal the policy (e.g. The Common Sense Nutrition Disclosure Act) and numerous delays in implementation, it is certain that public health will have future opportunities to engage with industry on these issues.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health for support in carrying out this study. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health helped support some of the time of the authors to facilitate the research project. Conflict of interest: No conflicts of interest were identified by the authors. Authorship: R.C.S. helped formulate the research question, design and carry out the study, analyse the data, and took the lead in writing the article. J.C. assisted in designing and carrying out the study, analysing the data and writing the article. G.L. assisted with carrying out the study and analysing the data. M.T. assisted with writing the article. G.M.W. assisted with writing the article. Ethics of human subject participation: No data on human subjects were involved, given that this was a publicly available data set available through the FDA, and no identifying information was collected or included about individuals.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016003025