The positive association between breakfast consumption and improved mental health status has been observed in adults(Reference Smith1) and young adults(Reference Smith2). However, breakfast may be especially important for children and adolescents who are not fully grown, as they have a larger brain to liver ratio than adults and therefore do not have the same ability to store required nutrients for periods of fasting(Reference Pollitt, Leibel and Greenfield3). Previous research reported by Lien(Reference Lien4) from the Oslo Health Study found that adolescents who ate breakfast daily were significantly less likely to be mentally distressed and more likely to have better school grades. However, the effect of breakfast quality on mental health in adolescence is yet to be reported. A review of breakfast quality and academic performance in children suggests that a good-quality breakfast with a variety of foods from different food groups can positively impact cognitive function(Reference Rampersaud, Pereira, Girard, Adams and Metzl5). Despite this potential benefit, prospective data suggest that the quality of breakfast declines as children move into adolescent years, where quality is defined by a lower consumption of core food groups at breakfast time(Reference Lytle, Seifert, Greenstein and McGovern6). Breakfast studies in children and adults indicate that not eating any breakfast, or consuming a poor-quality breakfast without items from core food groups, may contribute to dietary inadequacies that are not compensated for at other meals(Reference Nicklas, Bao, Webber and Berenson7, Reference Kerver, Yang, Obayashi, Bianchi and Song8) and may lead to higher consumption of energy-dense snacks later in the day(9).

Suboptimal nutrient intake or meal skipping has been associated with adverse effects on brain function in different population groups for areas such as attention and memory(Reference Wesnes, Pincock, Richardson, Helm and Hails10), mood(Reference Benton, Griffiths and Haller11) and behaviour(Reference Simeon and Grantham-McGregor12), suggesting a possible link with overall mental health. Investigating links between mental health and nutrition in young people is especially important as adolescence is a crucial period for the development of behavioural patterns and social skills that will influence the individual’s later adult functioning(Reference Bellisle13). Half of all lifetime cases of psychological disorders emerge by age 14 years(Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin and Walters14), making early adolescence an appropriate stage to examine factors associated with mental health.

The aims of the present study were to evaluate breakfast consumption patterns in early adolescence and to investigate the cross-sectional association between breakfast quality and mental health scores, using data from the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study. The Raine Study provides an ideal opportunity to investigate this relationship as it is a large, population-based cohort with data available on physical, socio-economic and lifestyle factors. We hypothesize that the consumption of a higher-quality breakfast is associated with better mental health status in adolescence.

Methods

Subjects

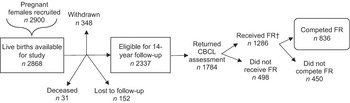

The Raine Study recruited 2900 pregnant women between 16 and 20 weeks’ gestation from May 1989 to November 1991 through the public antenatal clinic at King Edward Memorial Hospital and private clinics in Perth, Western Australia. Of the initial cohort, 2868 live births were available for follow-up. Study enrolment methods have been reported elsewhere(Reference Newnham, Evans, Michael, Stanley and Landau15). In the current paper we report cross-sectional results collected from the 14-year follow-up (mean age 14·0 (sd 0·2) years, range 13·0–15·0 years), as this follow-up was the first to comprehensively assess dietary intake and allow assessment of breakfast-eating habits. Derivation of the study sample from the overall Raine Study cohort is depicted in Fig. 1. Parents or primary caregivers completed the assessment of mental health using the Child Behaviour Checklist tool for 1784 adolescents. Of these, 1286 attended the assessment at the research centre and received a 3 d food record to assess breakfast intake. A total of 836 adolescents returned completed food records for a response rate of 65 % (836/1286). The ethics committees of King Edward Memorial Hospital and Princess Margaret Hospital approved the protocol for the Raine Study. Each adolescent plus their parent or guardian provided written consent for participation in the study.

Fig. 1 Derivation of the study sample from the overall Raine Study cohort; 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia (CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist; FR, food record). †Food records and the accompanying measuring utensils and instructions were handed out only to subjects who attended the in-person follow-up session at the Telethon Institute for Child Health Research in Perth, Western Australia. Some follow-up items including the CBCL were completed through the mail; for these items subjects were not required to attend the follow-up session at the Institute

Assessment of breakfast

The 3 d estimated food record in household measures was chosen to assess breakfast intake as the 3 d record has shown good validity in a child population(Reference Crawford, Obarzanek and Morrison16). A standard 3 d food record booklet with instructions was provided to participants who attended the 14-year follow-up assessment at the Telethon Institute for Child Health Research in Perth, Western Australia. A set of metric cups and spoons was provided to each study adolescent. Food records were completed by the adolescents themselves, with parental support if requested. The completed food records were individually checked by the study dietitian as they were returned, with clarification of data over the telephone where required(Reference Di Candilo, Oddy, Miller, Sloan, Kendall and de Klerk17).

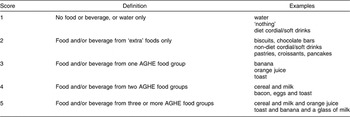

Breakfast was defined as the food and/or beverage items documented in the food record booklet under the breakfast heading, listed as the first meal of the day. The breakfast score described by Radcliffe et al.(Reference Radcliffe, Ogden, Coyne and Craig18) was used as the basis of our breakfast quality variable. This score is based on the five core food groups as defined by the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib19): (i) breads and cereals (including breakfast cereals, bread and rice); (ii) vegetables; (iii) fruit; (iv) dairy products (including soya milk products); and (v) meat and meat alternatives (including eggs, vegetarian meat alternatives and nuts). These food groups supply different nutrients essential to health and development, and adequate intake from all groups on a daily basis is recommended. Food or drink items which are not categorized into one of the core food groups are classified as ‘extras’, as they provide some nutrients but are not considered to be good sources of essential nutrients; this category includes items high in sugar and/or saturated fat such as soft drinks, biscuits, cake, pancakes and chocolate bars, as well as high-fat savoury goods such as pastries and sausage rolls(Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib19). Each breakfast listed in the food record was evaluated according to the number of core food groups consumed at that meal to create a breakfast quality score. The breakfast quality score ranged from 1 point, representing no food or drink, to 5 points, representing foods from three or more different food groups (Table 1). A breakfast of ‘extras’ was ranked above no food or drink, but less than a core food group. In instances where subjects consumed ‘extras’ in addition to core food groups, the ‘extras’ did not contribute to the score. This was because the breakfast quality score was intended to represent the intake of required nutrients as provided by the core food groups, rather than representing excess intakes of fat, sugar and salt. For example, if a subject ate foods from two food groups plus ‘extras’ foods, the score of 4 reflected intake of the two food groups only. Scores over the three days were averaged to create an overall breakfast quality score for each participant.

Table 1 Scoring system used to assess breakfast quality as determined by core food groups consumed(Reference Radcliffe, Ogden, Coyne and Craig18); 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia

AGHE, The Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib(19).

Assessment of mental health

Mental health was assessed using the 118-item Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL/4-18) for Ages 4–18 years, a validated measure of behaviour by parent or primary caregiver report(Reference Achenbach and McConaughy20). The CBCL provides a dimensional measure of child and adolescent behaviour and is used to assess mental health over the preceding six months. The CBCL produces a raw score which can be converted into three summary T-scores, referred to as ‘scores’ in the current paper: total behaviour, internalizing behaviour and externalizing behaviour. The internalizing behaviour score incorporates syndromes of withdrawal, somatic complaints and anxious/depressed; the externalizing behaviour score incorporates syndromes of delinquency and aggression(Reference Achenbach and McConaughy20). Three remaining syndromes of social, thought and attention problems contribute to the total behaviour score but not to the internalizing or externalizing scores. Higher scores are associated with more disturbed emotions and behaviours, with a total T-score of 60 or above classified as the clinical range for mental health morbidity(Reference Achenbach21). Use of the CBCL as a mental health assessment tool in both clinical and community settings has been supported in a recent meta-analysis(Reference Warnick, Bracken and Kasl22) and the CBCL has been shown to have good test–retest reliability in a Western Australian child population(Reference Zubrick, Silburn, Gurrin, Teoh, Shepherd, Carlton and Lawrence23). The internal consistency for the CBCL is r = 0·94 (Cronbach’s α = 0·97) for the total score, r = 0·91 (Cronbach’s α = 0·90) for the internalizing score and r = 0·92 (Cronbach’s α = 0·94) for the externalizing score(Reference Achenbach21).

Confounding variables included in the model

Physical measurements

Weight status may influence aspects of mental health such as depression in adolescents(Reference Rierdan and Koff24). Height and weight measurements were taken by a trained research assistant using standard calibrated equipment to calculate BMI as [weight (kg)]/[height (m)2]. BMI categories of underweight, normal weight overweight and obese were defined using standard criteria for this age group(Reference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson25, Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz26): (i) underweight, BMI ≤ 16·41 kg/m2 in males and ≤16·88 kg/m2 in females; (ii) normal weight, BMI = 16·42–22·61 kg/m2 in males and 16·89–23·33 kg/m2 in females; (iii) overweight, BMI = 22·62–27·62 kg/m2 in males and 23·34–28·56 kg/m2 in females; and (iv) obese, BMI ≥ 27·63 kg/m2 in males and ≥28·57 kg/m2 in females.

Sociodemographic and family characteristics

Socio-economic factors such as family income have been associated with both child behaviour problems(Reference Bor, Najman, Andersen, O’Callaghan, Williams and Behrens27) and breakfast frequency(Reference Gleason28). Evidence suggests that family characteristics may also affect the behaviour of children in the family(Reference Najman, Behrens, Andersen, Bor, O’Callaghan and Williams29). Information regarding maternal age at conception, maternal education, current family income, family structure and family functioning were obtained by parent report. Maternal age at conception was classified as: (i) <20 years; (ii) 20–29 years; or (iii) ≥30 years. Maternal education was assessed by the highest school year completed, with responses grouped as: (i) grade 10 or less; (ii) grade 11; or (iii) grade 12. Current family income was defined as the annual income for the household before tax at the time of the survey and was assessed categorically in three groups as follows: (i) <$AU 35 000; (ii) $AU 35 000–70 000; and (iii) >$AU 70 000 per annum. Family structure was assessed as either yes or no for living in a single-parent family. The General Functioning Scale from the McMaster Family Assessment Device was used to assess family functioning(Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop30). This short-form scale consists of twelve statements that were derived from an item analysis of the complete sixty-item scale, and includes questions on family communication, affective responsiveness and behaviour control. Lower scores on the General Functioning Scale represent poorer family functioning and higher scores represent better family functioning. This scale has been shown to be reliable (r = 0·83) and internally consistent (r = 0·86)(Reference Byles, Byrne, Boyle and Offord31).

Lifestyle factors

In addition to increasing dietary energy requirements, increased regular physical activity may assist in the management of mild-to-moderate mental health problems(Reference Paluska and Schwenk32). Likewise, sedentary behaviour may have the opposite effect. The lifestyle factors included in analysis for the present study were physical activity in leisure time and computer or television screen usage. In addition, an estimate of overall diet quality was also chosen as a confounding variable to adjust for usual nutrient intake over the whole day. Education level was not included as a confounding variable as school education in Western Australia is mandatory until age 15 and all adolescents in this study were aged 13·0 to 15·0 years.

To determine physical activity level, adolescents were asked how often they exercised outside of school hours per week, where exercise was defined as activity causing breathlessness or sweating. These data were converted into an ordinal variable with three levels: (i) exercise <1 time/week; (ii) exercise 1–3 times/week; and (iii) exercise ≥4 times/week. As a proxy measure of sedentary behaviour, adolescents were asked about their television or video viewing and computer use, measured as hours per day of combined screen use. This data was categorized into three levels: (i) <2 h/d; (ii) 2–4 h/d; and (iii) >4 h/d.

We collected information on overall diet using a 221-item FFQ provided by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation that has been validated in adults and previously applied in children(Reference Baghurst and Record33, Reference Rohan, Record and Cook34). To represent the overall nutritional value of individual diets, a diet quality score was developed based on similar scores published in the international literature(Reference Haines, Siega-Riz and Popkin35). The diet quality score consisted of thirteen dietary components, including both nutrients and food groups, with each component given a score out of 10 based on degree of compliance with Australian dietary recommendations(Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib19), for a total possible score of 130.

Statistical analyses

Breakfast quality was analysed as both a continuous and categorical variable. For the categorical variable, no breakfast and ‘extras’ only were combined due to low subject numbers in these groups. The χ 2 test was used to investigate associations between potential risk factors and breakfast quality. Pearson’s correlation was used to determine the association between breakfast quality and overall diet quality. ANOVA was applied to assess differences in mean mental health score between breakfasts of differing core food groups, with Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test used for post hoc analysis. A general linear model was applied to examine the relationship between breakfast quality and mental health adjusted for confounding variables; variables were entered simultaneously. Independent t tests and χ 2 tests were used to examine differences between adolescents who completed the food record and those who did not. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) statistical software package version 15·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The mean total mental health score as assessed by the CBCL was 45·24 (sd 11·29), with mean internalizing behaviour score of 45·87 (sd 10·53) and mean externalizing behaviour score of 46·58 (sd 10·52). Within the study group, 11·0 % of adolescents were categorized in the clinical range for mental health morbidity.

For breakfast quality, the mean score was 3·70 (sd 0·75). Skipping breakfast on at least one of the three days was reported by 14·6 % (n 122) of adolescents; overall, 1·1 % (n 9) reported skipping breakfast each day over the 3 d period. An average breakfast of ‘extras’ food alone over the 3 d period was reported by 5·6 % (n 47) and food from one food group was reported by 27·9 % (n 233). The majority of adolescents (54·0 %, n 452) consumed a breakfast consisting of food from two different food groups over the three days, while a high-quality breakfast consisting of three or more food groups was consumed by 11·4 % (n 95). Milk, followed by fortified breakfast cereals and bread, were the food and beverage types most commonly consumed by the adolescents for breakfast.

Breakfast quality was positively associated with overall diet quality (r = 0·28, P < 0·001). Adolescents who reported lower breakfast quality scores were significantly more likely to be female, have mothers with a younger maternal age and a lower level of maternal education, come from lower-income families, have higher screen use and be less physically active than adolescents who reported higher breakfast quality scores (Table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of study adolescents for each breakfast quality level; 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia

†Defined according to BMI classification groupsReference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson(25, Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz26).

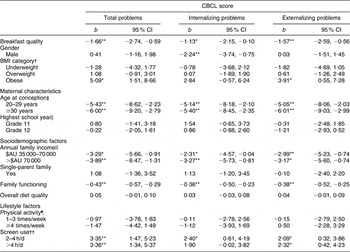

There was a stepwise decrease in total mental health score for each increase in breakfast quality ranking (P = 0·009, Fig. 2), representing improved mental health. A multivariable general linear model incorporating potential confounding factors showed that a higher breakfast quality score was significantly associated with a lower total CBCL score (b = −1·66; 95 % CI −2·74, −0·59; P = 0·002; Table 3), equating to a decrease in the total CBCL score of 4·8 from no food groups eaten at breakfast to three or more food groups eaten at breakfast. A higher breakfast quality score was also significantly associated with lower internalizing behaviour scores (b = −1·13; 95 % CI −2·15, −0·10; P = 0·031) and lower externalizing behaviour scores (b = −1·57; 95 % CI −2·59, −0·56, P = 0·002).

Fig. 2 Total mental health scores, as assessed by the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL), for the varying breakfast categories based on core food groups (ANOVA test for trend P = 0·009); 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia. Values are means with their 95 % confidence intervals represented by vertical bars. a,bMean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05, post hoc analysis using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test)

Table 3 Adjusted regression coefficients in the multivariate general linear model for mental health, as assessed by the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL); 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia

Association was significant: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†Defined according to BMI classification groupsReference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson(25, Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz26); reference category: normal weight.

‡Reference category: mothers aged <20 years at conception.

§Reference category: grade 10 or less.

||Reference category: annual family income <$AU 35 000.

¶Reference category: <1 time/week.

††Reference category: <2 h/d.

The characteristics of the study sample were compared with the other adolescents in the 14-year Raine Study follow-up who did not complete a food record (Table 4).

Table 4 Frequency characteristics for study participants who completed the CBCL and the food record (n 836) compared with the study participants who completed the CBCL but did not complete the food record (n 948); 14-year follow-up of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, Perth, Western Australia

CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist.

Differences between subjects who did and did not complete the food record were significant: *P < 0·05.

†n 805 for subjects who did not complete the food record.

‡Defined according to BMI classification groupsReference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson(25, Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz26).

Discussion

Our results support the hypothesis that higher breakfast quality is associated with better mental health in adolescence. Compared with skipping breakfast, eating a breakfast with foods from three or more core food groups was associated with a decrease in total CBCL total score of 4·8 points, approximately 10 % of the mean CBCL score. The difference in score was independent of confounding factors and is potentially clinically meaningful. Of particular interest in our results was the stepwise decrease in total mental health score with increasing breakfast quality, suggesting a possible dose–response relationship.

Previous studies have found a similar relationship between mental health and breakfast cereal consumption in populations of adults(Reference Smith1) and young adults(Reference Smith2), and with breakfast regularity in adolescents(Reference Lien4). The present research takes the relationship one step further by showing an association between the quality of breakfast and mental health. The breakfast quality of boys in our study was significantly better than for girls, a trend that has also been found in terms of breakfast consumption or quality in other adolescent population groups in Spain(Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem, Ribas and Pérez-Rodrigo36), Belgium(Reference Matthys, De Henauw, Bellemans, De Maeyer and De Backer37) and Norway(Reference Lien4).

Breakfast can potentially influence mental health in a number of ways. In terms of nutrient intake, milk, fortified breakfast cereals and bread, the most common foods consumed for breakfast by the Raine Study adolescents, are good sources of nutrients that affect brain function, including carbohydrate, Ca, B vitamins, Fe and folate. As the association with breakfast and mental health was independent of our indicator of overall diet quality, the consumption of these breakfast foods at the start of the day may be particularly beneficial.

All core food groups except meat and meat alternatives supply carbohydrate which is converted to glucose, the metabolic fuel required for brain function. Blood glucose concentrations are closely regulated by the body; however, short-term variation of glucose availability can affect the brain even when adequate nutritional status exists(Reference Bellisle13). For example, a double-blind trial by Benton et al.(Reference Benton, Brett and Brain38) found that ingestion of a glucose drink two hours after lunch improved attention and reaction to frustration in children. When blood glucose concentrations fall below normal, hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol are released which are associated with feelings of agitation and irritability; symptoms such as difficulty concentrating and destructive outbursts can also occur(Reference Fishbein and Pease39). The breads and cereals food group is the most carbohydrate-dense of the food groups and incorporation of these foods into breakfast, in suitable portion sizes, may help to avoid low blood glucose concentrations. These behaviours of aggression and delinquency were encompassed into the externalizing mental health score, which showed a stronger association with breakfast quality in our study than the internalizing mental health score, which included syndromes of depressive behaviour and withdrawal.

As well as carbohydrate, intake of vitamins and minerals also affects brain function. A variety of vitamins and minerals assist with optimal functioning of neurotransmitters, chemicals used to communicate information between neurons in the nervous system. Neurotransmitters are directly responsible for aspects such as behaviour, mood and intellectual function. Although severe malnutrition would be required to cause neurotransmitter deficits serious enough to result in neurological impairment, changes in everyday diet may result in subtle changes(Reference Fishbein and Pease39). Milk, the most popular breakfast item consumed by the Raine Study adolescents, provides Ca which is involved in the release of neurotransmitters(Reference Kaplan, Field, Crawford and Simpson40). Milk also contains tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin and a neurotransmitter involved in psychological processes. Breads and fortified breakfast cereals are good sources of the B vitamins thiamin and pyridoxine. These vitamins assist in attentional processes, synthesis of neurotransmitters and carbohydrate metabolism(Reference Blokland41, Reference Hartvig, Lindner, Bjurling, Långström and Tedroff42). As B vitamins are water-soluble, body stores are relatively small and can decline over a period of a few weeks in the absence of sufficient dietary intake. Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies show that thiamin supplementation improves composure, mood and clarity of thought, even in subjects who are classified as having adequate thiamin status(Reference Benton, Griffiths and Haller11, Reference Benton, Haller and Fordy43). Fortified breakfast cereals are also good sources of folate and Fe, which are used in the synthesis of serotonin(Reference Young44) and other neurotransmitters(Reference Hutto45); Fe is additionally used to bind neurotransmitters to receptors in the brain(Reference Jimenez Del Rio, Velez Pardo, Pinxteren, De Potter, Ebinger and Vauquelin46).

An increased intake of valuable vitamins and minerals at the start of the day, resulting from consumption of a breakfast with a variety of food groups, may partially explain the relationship with better mental health that was observed in our study. Other explanations may include regular eating leading to improved quality of sleep(Reference Tanaka, Taira, Arakawa, Masuda, Yamamoto, Komoda, Kadegaru and Shirakawa47) or fibre from breakfast cereal assisting with bowel function and reduced fatigue(Reference Smith, Bazzoni, Beale, Elliott-Smith and Tiley48). A behavioural clustering effect may also be present: a positive association between breakfast quality and our indicator of overall diet quality was found in our study, and Lien(Reference Lien4) notes that adolescents who eat breakfast and other meals regularly are more likely to display other healthy behaviours, such as a good diet, lower alcohol consumption and abstinence from smoking.

Our study had three notable strengths. The first was the large population-based cohort and assessment of a wide array of variables, including lifestyle factors, BMI, and family and sociodemographic characteristics. Poor breakfast quality was shown to be associated with adverse mental health independently of these factors and therefore independent of the established relationship between low socio-economic status and poor nutritional intake(Reference Shahar, Shai, Vardi, Shahar and Fraser49) and between poor family functioning and mental health problems(Reference Bond, Toumbourou, Thomas, Catalano and Patton50). The second strength of our study was the use of the CBCL, a well-researched and validated measure of mental health morbidity that has shown good sensitivity in the diagnosis of adolescent psychopathology(Reference Warnick, Bracken and Kasl22). The third strength of the study was the use of 3 d food records which were checked by a trained dietitian for precise determination of breakfast quality(Reference Di Candilo, Oddy, Miller, Sloan, Kendall and de Klerk17).

Interpretation of our study results are limited by the cross-sectional design. The association observed may also be due to poor mental health leading to a lower-quality breakfast. For example, some people experiencing emotional distress such as depression may lose their appetite or report a craving and preference for sweet carbohydrate- and fat-rich foods(Reference Christensen51). These comfort foods, such as chocolate, stimulate endorphin release in the brain to elevate mood(Reference Benton and Donohoe52). In addition, positive mental health behaviours may be a result of overall higher self-efficacy and self-esteem rather than as a result of dietary factors. Good dietary patterns have been linked with other positive healthy lifestyle behaviours(Reference Liebman, Pelican and Moore53), a trend that was also observed in our study, with higher breakfast quality scores significantly associated with increased levels of physical activity.

The prevalence of clinical mental health morbidity in our subject group was 11·0 %, slightly lower than the national estimate of 13·1 % obtained from the national mental health survey of 13–17-year-old adolescents(Reference Sawyer, Miller-Lewis and Clark54). Generalization of the results from our study to the wider adolescent population must be done with caution, due to the differences existing between those adolescents who completed the food record compared with those who did not. Adolescents who took the time to complete the food record and return it were less likely to have mental health problems (Table 4). In addition, adolescents who completed the food record were more likely to have better overall diet quality, be less obese, have older and more educated mothers, a higher family income and a two-parent family. Nevertheless, the variance within the subject group was still large enough to observe a significant association between breakfast quality and mental health in the Raine Study.

In summary, our study supports the concept that breakfast quality is a significant component in the complex interaction between lifestyle factors and mental health in adolescence. We found that a higher-quality breakfast, consisting of foods from multiple food groups, was significantly related to better mental health scores in adolescents after adjustment for a number of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. Intervention studies will also help to further define this relationship, particularly through examination of meal patterns and nutrients that may exert an influence on externalizing behaviours. Potential public health implications of this and future research include the development of adolescent-focused education on the importance of breakfast, particularly for girls, and the incorporation of breakfast programmes into high schools.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Chief Investigators of the Raine Study, the Study Executive and Study Staff for their ongoing commitment to data collection. We would especially like to acknowledge Kathryn Webb as the Raine Study dietitian from 2004 to 2006, and Professor Nick de Klerk for statistical advice. Special thanks go to the Raine Study adolescents and their families for their participation in the research.

Sources of funding: The Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study is funded by the Raine Medical Research Foundation at The University of Western Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Telstra Research Foundation, the Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation, and the Australian Rotary Health Research Fund.

Conflict of interest declaration: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship contributions: Planning research (W.H.O., G.E.K., M.M., S.R.S.); executing research (W.H.O., G.E.K., M.M., S.R.S.); analysing data (M.R., T.A.O’S., P.J., W.H.O.); interpreting data (T.A.O’S., M.R., P.J., W.H.O.); and writing (T.A.O’S., M.R., W.H.O., S.S.).