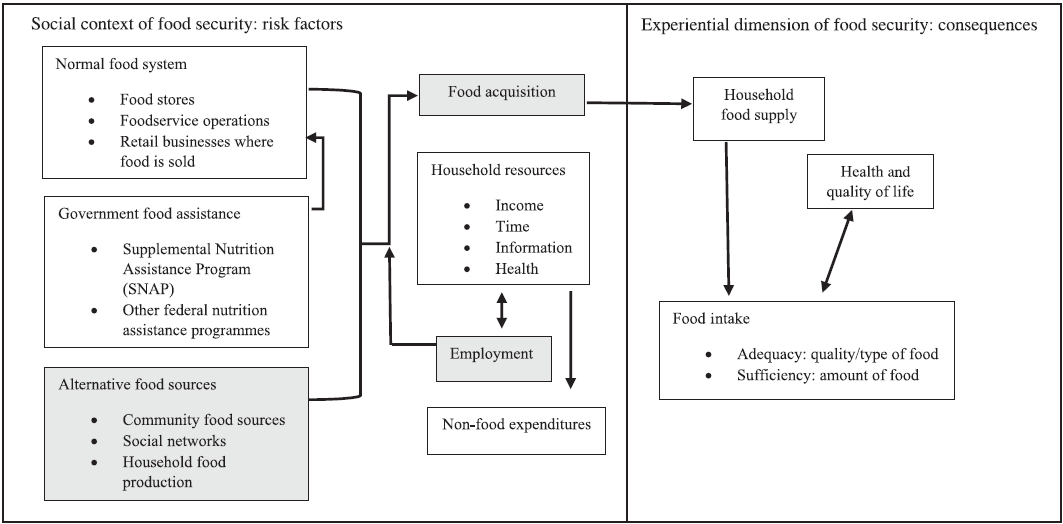

Food insecurity occurs when the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire suitable foods in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain(Reference Klein1). During 2018, 14·3 million (11·1 %) US households experienced food insecurity at some point(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory2). Of all US households, 6·8 % had low food security, while 4·3 % had very low food security(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory2). Low-income households have greater vulnerability to food insecurity due to financial constraints and thus may engage in other food acquisition practices to meet food needs. According to Campbell’s framework for the conceptualisation of food insecurity and its risk factors, households obtain food from three types of sources, defined as (1) food purchased from the normal food system, (2) food facilitated from government food assistance and (3) food acquired through alternative strategies. The normal system refers to food available for purchase at grocery stores, food service operations and other retail businesses(Reference Campbell3). The second source highlighted refers to food facilitated by the multitude of food assistance programmes for vulnerable families in the USA (e.g. the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance for Women, Infants and Children, National School Lunch Program School, School Breakfast Program, and Summer Meal Program, among others)(Reference Campbell3). The third type of food sources is alternative food sources, which allow families to acquire food free of cost from private food assistance, gifts from family and friends, scavenging, gardening, hunting and fishing(Reference Campbell3). A recently modified version of Campbell’s framework (Fig. 1) identified an additional food source for some low-wage workers: (4) food from place of employment(Reference Beck, Quinn and Hill4).

Fig. 1 Modified model of Campbell’s framework for US household food security(Reference Campbell3,Reference Beck, Quinn and Hill4)

Alternative food sources

Alternative food acquisition refers to the resourceful strategies that households use to acquire foods free of cost from formal and informal sources in their environment(Reference Campbell3). Campbell proposes that for most families, purchasing from the normal food system is the primary, socially acceptable source of food and government food assistance is used when household resources are constrained(Reference Campbell3). Structural and financial barriers to food purchasing and government food assistance are commonly considered to be risk factors for household food insecurity(Reference Anater, McWilliams and Latkin5–Reference Walker, Keane and Burke11). However, few generalisable studies address the frequency of alternative food acquisition and whether alternative acquisition strategies are differentially used by food-secure or food-insecure households.

We have framed alternative food acquisition around shared characteristics of the food source and categorised these into food acquisition from: (1) community programmes (e.g. food pantries, meal delivery programmes, soup kitchens and place of worship), (2) social networks (e.g. family, friends, neighbours and at work) and (3) household production (e.g. growing food, fishing and hunting).

Community food sources

Community-based food assistance programmes were designed as temporary measures to relieve short-term economic hardship(Reference Biggerstaff, Morris and Nichols-Casebolt12,Reference Weinfield, Mills and Borger13) . However, as income and SNAP benefits are often insufficient in meeting household food needs, food pantries and meal centres have become long-term adaptive strategies used by many vulnerable populations in the USA(Reference Bacon and Baker14). These programmes vary widely in their scope of service (e.g. eligibility, number of persons served and types of foods) and their accessibility (e.g. schedule and location) to low-income households across the USA(Reference Weinfield, Mills and Borger13).

Food from social networks

Social support includes emotional, informational (e.g. providing information about where to find food) or instrumental support (e.g. sharing food) from an individual’s network of connection to others(Reference Chhabra, Falciglia and Lee15). Parents in food-insecure households have identified sending their children to eat at someone else’s house(Reference Wood, Shultz and Edlefsen16) and asking for food or trading food(Reference Gorman, McCurdy and Kisler17) as strategies to cope with food insecurity. However, expectations of food sharing may also lead food-insecure households to give food away, which may further strain their resources(Reference Garasky, Morton and Greder18).

Household food production

Households with access to the necessary resources (e.g. skill, knowledge, physical ability, space, materials and equipment) may produce their food by growing food, hunting or fishing seasonally and storing these foods for later consumption. The literature on household food production primarily focuses on food production as a means for community development and improved dietary intake(Reference Turner, Henryks and Pearson19–Reference Twiss, Dickinson and Duma22). While there is sparse information about the influence of gardening, fishing and hunting on food security in high-income countries, previous qualitative studies have reported positive impacts of household food production on food security in some North American communities(Reference Kortright and Wakefield23–Reference Colón-Ramos, Thompson and Yaroch26).

Much of the research on food acquisition has focused on the resourceful strategies low-income households use to purchase foods (e.g. couponing and bulk purchases) and the contributions of federal food assistance to each household’s food supply(Reference Anater, McWilliams and Latkin5–Reference Walker, Keane and Burke11). In determining whether alternative food acquisition ameliorates food insecurity, previous studies have utilised convenience samples from individuals already using at least one type of federal or community food assistance(Reference Beck, Quinn and Hill4,Reference Biggerstaff, Morris and Nichols-Casebolt12,Reference Chhabra, Falciglia and Lee15–Reference Gorman, McCurdy and Kisler17,Reference Carney, Hamada and Rdesinski24,Reference Kempson, Keenan and Sadani27–Reference Hoisington, Shultz and Butkus34) . To build on these results, we used data from the FoodAPS to characterise the use of alternative food sources in a nationally representative sample of low-income US households. Specifically, we determined: (1) the characteristics of households who use alternative food sources and (2) whether a household’s food security status is associated with the use of alternative food acquisition strategies.

Methods

Sample

This study used data from FoodAPS, which is managed by the Economic Research Service and designed by Mathematica Policy Research (Mathematica). Complex, multistage probability sampling was used to enrol approximately 4600 households. Households were sampled according to the following characteristics: (1) households receiving SNAP benefits, (2) non-SNAP households with income less than the federal poverty line (FPL), (3) non-SNAP households with income from 100 to 185 % of the FPF and (4) non-SNAP households with income greater than 185 % of the FPL.

Households were recruited and interviewed from April 2012 to January 2013. Each sampled household was screened to determine eligibility and to determine the household member responsible for food acquisition (designated as the primary respondent). Primary respondents who qualified for and participated in the survey were trained to document information on the foods all household members acquired over 7 days using a barcode scanner and notebooks. The primary respondent also participated in two in-person interviews and up to three follow-up telephone interviews. Data were collected from 4826 households. The overall response rate was 41·5 %. In accounting for the complex sampling design, weights were created to be representative of all non-institutionalised households in the continental USA and to address nonresponse bias. We included households with incomes at or below 185 % of the FPL (n 2535) and excluded households with incomplete data for all variables of interest (n 1) for a final analytical sample of 2534. Since the FoodAPS data were collected in 2012, the 2012 FPL was used as a cut-off to determine whether households were low income.

Alternative food acquisition (dependent variables)

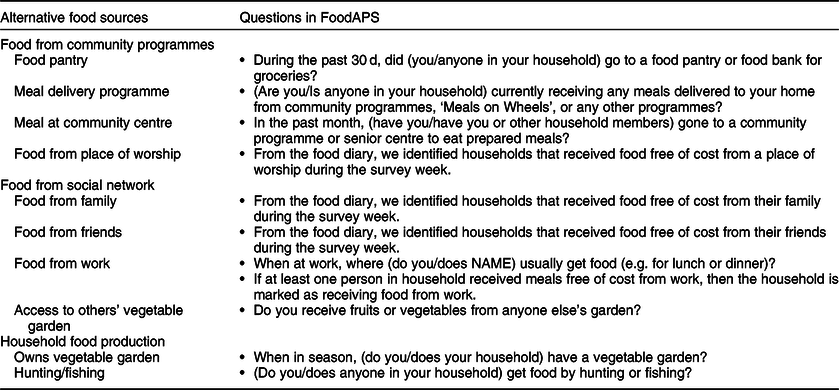

The use of each alternative food acquisition strategy was constructed as a binary variable based on the questions shown in Table 1. A household was categorised as using community food sources if they responded ‘yes’ to (1) currently using a meal delivery service (e.g. Meals on Wheels), (2) received food from a community centre in the past month, (3) attended a food pantry in the past 30 d or (4) received food from a place of worship during the survey week. If they replied ‘no’ to all of these questions, they were categorised as not using community food sources. A household was categorised as receiving food from their social network if they received food free of cost from someone else’s garden when in season or if they received food from their family, friends or workplace at least once during the survey week. If they did not report receiving food from someone else’s garden (in season), or from family, friends, work or during the survey week, they were categorised as not receiving food from social networks. A household was categorised as producing food if they reported having a vegetable garden, going fishing or hunting in season. If they replied no to all of these questions, the household was categorised as not producing food. The alternative food source categories were nonexclusive (e.g. households could receive food from one, two or all three types of food sources). A household was categorised as using alternative food acquisition if they received food from at least one of the three alternative sources.

Table 1 Questions from the FoodAPS used to categorise alternative food acquisition strategies

Food security (independent variable)

The independent variable was household food security status for 30 d prior to the final interview. Food security status was collected using the ten-item USDA Adult Food Security Survey Module modified to use a reference period of the previous 30 d(35). In responding to yes/no and frequency response sets, households that reported no affirmative responses were categorised as food secure, households reporting one or two affirmative responses as marginally food secure, households reporting three to five affirmative responses as having low food security and households reporting six or more affirmative responses as having very low food security.

Covariates

We included covariates that, theoretically, could affect both a household’s susceptibility to food insecurity and their ability to acquire food through alternative strategies. Covariates described both the households’ and the primary respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics. The household-level variables included: percentage of the FPL (range 0–185 % FPL), number of household members, whether there were children in the home (yes/no), homeownership (yes/no), car ownership (yes/no), rurality (yes/no), household members’ participation in at least one of the following federal food assistance programmes: SNAP, Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance for Women, Infants and Children, National School Lunch Program or School Breakfast Program (yes/no). Primary respondent characteristics included: race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, or other race/ethnicity), country of birth (USA/non-USA), sex (male/female), marital status (married/not married), age group (18–35, 36–59 or 60+ years of age) and educational attainment (less than high school, high school/GED, some college, or Bachelor’s degree and higher). The most parsimonious model is presented and includes the following variables: percentage of the FPL, born in the USA, age group, household size and homeownership.

Statistical analyses

For all analyses, we used weights provided by Mathematica to correct for differential selection probabilities and to adjust for nonresponse. The masked variance unit variable and the stratum variable were used to estimate variances with the Taylor series linearisation to account for the complex sampling design used to collect FoodAPS data. We calculated weighted percentages, means and 95 % CI to describe demographic characteristics of the total sample, alternative food acquisition users and non-users. We tested for differences among users and non-users by performing χ 2 analyses for proportions and t tests for means and standard errors.

Logistic regressions were used to examine the odds of using alternative food acquisition strategies (dependent variable) for households of varying levels of food insecurity compared with fully food-secure households (independent variable). A backward stepwise model was used to select the final list of covariates included in the model. F-partial statistics were examined at an alpha-to-remove value of 0·10. Additionally, covariates were removed if there was evidence of multicollinearity. Multicollinearity was examined by exploring the condition indices and variance inflation factors. A cut-off of 30 was used for condition indices and 5·0 for variance inflation factors. We corrected for multiple comparisons with a Bonferroni Correction (an alpha of 0·5 divided by three tests = 0·017). All statistical analyses were completed using SAS 9.4v.

Results

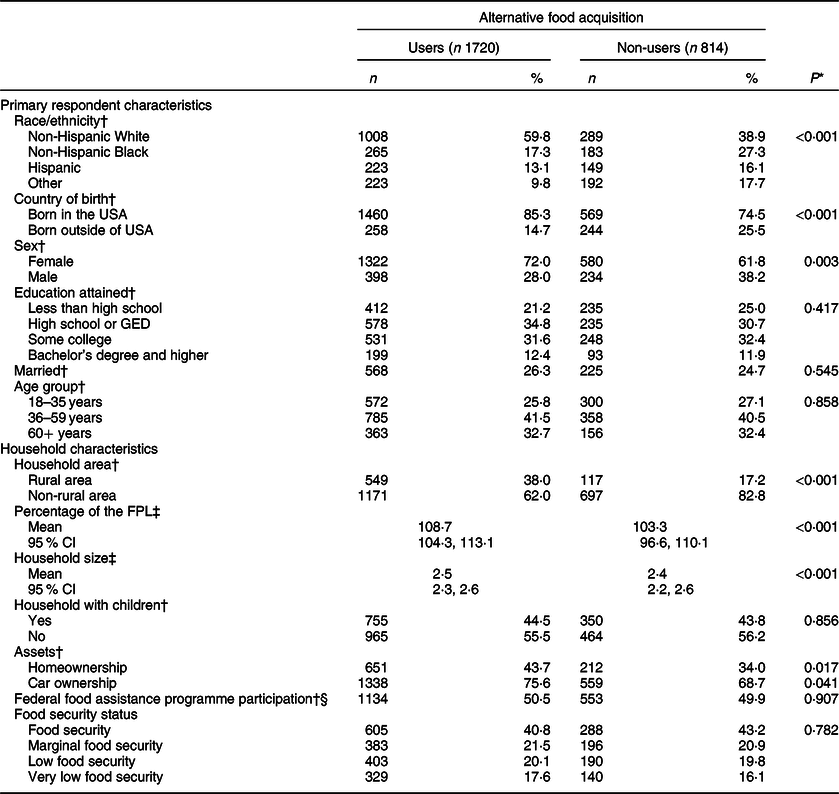

We examined the use of alternative food acquisition among low-income households in the USA. Table 2 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of low-income households and primary respondents. Among our sample, 69·6 % engaged in some form of alternative food acquisition strategy. Households using alternative food acquisition strategies were more likely to have a primary respondent who was non-Hispanic White, born in the USA, female, and living in a rural area, had higher income and owned a home compared with households that were not using alterative food acquisition strategies.

Table 2 Characteristics of low-income (<185 % FPL) US households by use of alternative food acquisition; FoodAPS (n 2534)

FoodAPS, National Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey; GED, general education development; FPL, federal poverty line.

* P-values correspond to χ 2 analyses for proportions and t tests for means and standard errors.

† For categorical variables, the unweighted counts and weighted percentages are provided.

‡ For continuous variables, means and 95 % CI are provided.

§ Participation in at least one of the following: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children, National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, and Summer Meal Program.

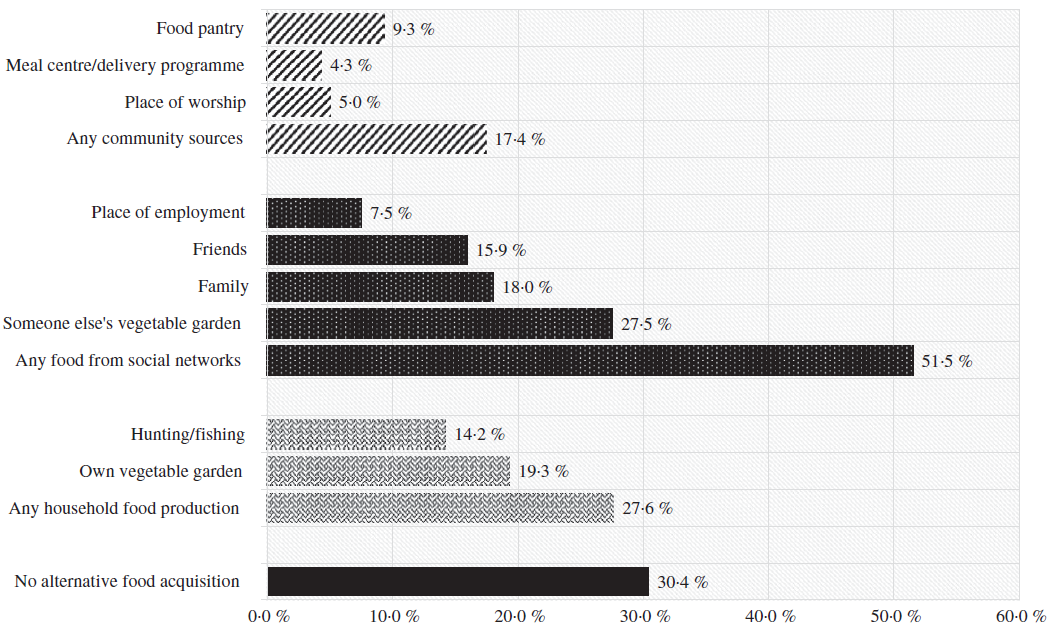

A total of 17·4 % of all households reported using at least one community food source in the previous month, 51·5 % reported receiving food from their social networks either in the recent week or from someone else’s garden during harvest season, and 27·6 % reported seasonal household food production (Fig. 2). Data describing sociodemographic characteristics by food acquisition strategies are available in the supplemental tables. While there was no difference in food security status among users of alternative food acquisition strategies compared with non-users overall, households using community food sources were more likely to have low food security (24·2 %) or very low food security (28·3 %) than households not using community sources (19·2 and 14·9 %, P < 0·01, respectively). Similarly, primary respondents using community sources were more likely to be 36–59 years old (51·2 %) and more likely to participate in federal food assistance programmes (58·9 %) than households not using community food sources (39·3 and 47·6 %, P < 0·01, respectively).

Fig. 2 Percentage of low-income US households using alternative food sources (n 2534). ![]() , Community food sources;

, Community food sources; ![]() , Social networks;

, Social networks; ![]() , Household food production

, Household food production

The prevalence of specific sources within each alternative food acquisition strategy category is shown in Fig. 2. The most commonly used community food source was food pantries (9·3 %). The most commonly used social networks were getting food from someone else’s garden during harvest season (27·5 %). For household food production, the most common source was owning a vegetable garden (19·3 %, Fig. 2).

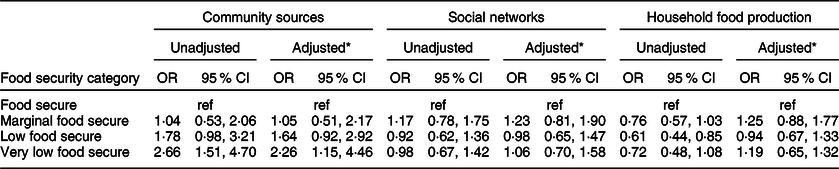

We subsequently determined the association between food security and receiving food from community sources, social networks and household food production (Table 3). Very low food security was positively associated with using any community sources in both the unadjusted (OR = 2·66, 95 % CI 1·51, 4·70) and the adjusted model (aOR = 2·26, 95 % CI 1·15, 4·46). We found no significant associations between marginal or low food security and community sources. Food security was not associated with receiving food from social networks, while low food security was inversely associated with household food production in the unadjusted model (OR = 0·61, 95 % CI 0·44, 0·85) only. We evaluated interactions between food security and income, food security and gender, and food security and having children in the household and performed stratification of the analysis (by income, gender and children in the household), and there was no significant effect modification in the association between alternative food acquisition and food security.

Table 3 Logistic regression results of the association between food security status (independent variable) and alternative food acquisition (dependent variable) among low-income USA households, FoodAPS (n 2534)

* Model was adjusted for the following characteristics: percentage of the FPL, born in USA, age group, household size and homeownership.

Discussion

We examined the alternative food acquisition among low-income households in the USA and its association with food security. Very low food-secure households were twice as likely to report using community food sources than food-secure households. This finding is similar to studies that have shown that because households with greater food precariousness may gain the most from using food banks and other meal programmes, these types of programmes are more likely to be used by food-insecure households(Reference Duffy, Zizza and Jacoby36,Reference Greder, Garasky and Klein37) . While community programmes may improve food access for the most vulnerable, we did not find an association between accessing community sources and higher levels of food security. Longitudinal studies should evaluate the extent to which households use community sources as a remedial strategy to alleviate existing hardship.

Overall, community food sources were the least used alternative food acquisition strategy for low-income households. Other studies have documented the discouraging obstacles to food pantries or soup kitchens, such as providing paperwork to prove eligibility, inconvenient locations, inconvenient and limited operating hours, and waiting in line to receive food(Reference Bhattarai, Duffy and Raymond8,Reference Fong, Wright and Wimer38–Reference Vissing, Gu and Jones41) . The social stigma of accessing food assistance in the USA has been well documented and is a primary barrier to many households, particularly those in close-knit communities (e.g. rural communities, college campuses)(Reference Fong, Wright and Wimer38,Reference Kindle, Foust-Newton and Reis40–Reference El Zein, Mathews and House44) . While we were unable to evaluate obstacles to strategy use in this study, we did find that only very low food-secure households were more likely to use these resources. On the other hand, low and marginally food-secure households did not use these strategies, despite potentially benefitting from participation in community food assistance programmes.

Even though approximately half of the low-income households used social networks to obtain food, we did not find that food-insecure households were more likely to use social networks than food-secure households. This may be partially explained by results from another study of 400 SNAP-participating families in which food-secure households were more likely to report strong, generous networks they could turn to during food hardship for monetary or instrumental support compared with food-insecure households(Reference Edin, Boyd and Mabli45). Contrary to our findings, some qualitative studies have found that when public assistance was not sufficient, households sought help from social networks before resorting to community-based food assistance(Reference Chhabra, Falciglia and Lee15,Reference Ahluwalia, Dodds and Baligh29,Reference Davis, Grutzmacher and Munger30,Reference Hamelin, Beaudry and Habicht46) . Others have shown that receiving support from social networks can be stressful, as individuals may want to reciprocate, but may not have the resources to do so(Reference Ahluwalia, Dodds and Baligh29,Reference Davis, Grutzmacher and Munger30,Reference Ajrouch, Reisine and Lim47) . If food exchange may strain households with limited resources, such strain could also partially explain the lack of association between food security and receiving food from social networks observed in this study. We found that receiving food from someone else’s vegetable garden and growing food in one’s garden were the most commonly reported food acquisition strategies. However, there was no significant association between food security and household food production after adjusting for covariates. Families reporting access to their own or someone else’s vegetable garden may have little control over the availability and stability of the food supply, thus potentially limiting its usefulness for consistent or sufficient access during periods of food insecurity. The viability of household food production is often constrained by seasonal availability, and the amount produced may be affected by extraneous factors such as weather, pests or available resources (e.g. gardening inputs, space to grow food and fishing/hunting equipment)(Reference Kigutha, Van Staveren and Veerman48–Reference Rosenzweig, Iglesius and Yang50). Also, variation in the amount of food a household produces from, for example, a small herb garden compared with a larger vegetable garden, may vary the impact of gardening on food insecurity. In contrast to our findings, other studies have identified vegetable gardens as essential tools to improve a household or community food security(Reference Meenar and Hoover51,Reference Brown and Jameton52) . Qualitative studies have found that home and community gardens not only improve household and community food availability, they also increase the availability of culturally appropriate foods(Reference Carney, Hamada and Rdesinski24), strengthen social networks(Reference Glover21,Reference Alaimo, Reischl and Allen53) and give households a sense of pride and self-reliance(Reference Kortright and Wakefield23). Increasing access to household food production for low-income households may be an important step to strengthening informal food safety nets of vulnerable populations at risk of food insecurity.

Study limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the FoodAPS data limited our ability to determine the temporality of the alternative acquisition in relation to food security status. However, it is reasonable to infer that the temporal relationship between need and acquisition reflects the likelihood that food insecurity led households to visit food pantries, rather than the possibility that visiting food pantries or other community programmes caused a household to become food insecure. Second, our focus for this study was limited to whether or not households of varying food security status use alternative food acquisition strategies. Future studies should evaluate the quantity, quality and frequency of food acquired as they relate to food security. Third, questions asking about the use of alternative food sources were framed with different recall time frames: whether households received food from community sources the last 30 d, from family and friends during the previous week, from their own or others’ gardens, or through hunting and fishing ‘in season.’ Thus, these time frames may not coincide with the 30-d food security questions. These data do, however, provide reasonable estimates of the regular use of alternative food acquisition strategies. Fourth, FoodAPS also had a moderately low response rate. To determine whether the low response rate may bias results, Mathematica completed a two-step nonresponse bias analysis. Twenty-five variables were associated with both nonresponse and key study variables; these variables were used to construct the sampling weights for the study. We used these sampling weights in the analysis to account for the complex sampling design and nonresponse. Finally, families experiencing housing instability or houselessness may be underrepresented in the sample. Their unique experiences using alternative food sources should be a focus of future studies.

Conclusion

A majority of households reported using at least one type of alternative food acquisition strategy, but only very low food security was positively associated with using community food sources. Despite being commonly reported, household food production and receiving food from social networks did not differ by food security status. To better understand the role of alternative food acquisition among low-income households, further research should explore the social acceptability of various strategies, the amount and types of foods acquired from alternative food sources, the mechanisms by which households acquire these foods, and the frequency of acquisition.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: M.C., PhD, RD worked to conceptualise and design the study and formulate research questions as part of her dissertation work. She completed data analysis, contributed to interpretation of results, wrote the first drafts of all sections and undertook major revisions. S.G., PhD substantially contributed to the study conception and design and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, language and formatting throughout its development. E.S., PhD, RD substantially contributed to the study conception and design, guided and revised data analysis and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content throughout its development. All coauthors approved the version submitted for review. Ethics of human subject participation: The current article does not involve human subjects under the regulations set forth by the Department of Health and Human Services 45 CFR 46.