In the USA in 2015, the prevalence of food insecurity, or inconsistent access to healthy foods, was 12·7 %, affecting almost 16 million households( Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt and Gregory 1 ). Women, children and people of colour are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity( 2 , Reference Roshanafshar and Hawkins 3 ). Food insecurity has been related to lower productivity( 4 ) and academic outcomes( Reference Jyoti, Frongillo and Jones 5 ), poorer nutritional health( Reference Bhattacharya, Currie and Haider 6 , Reference Chilton, Black and Berkowitz 7 ) and higher rates of chronic disease such as diabetes( Reference Seligman, Bindman and Vittinghoff 8 , Reference Berkowitz, Baggett and Wexler 9 ). Those who struggle with food insecurity often report struggling with mental health( Reference Hromi-Fiedler, Bermúdez-Millán and Segura-Pérez 10 – Reference Weaver and Hadley 14 ).

Concurrent food insecurity and emotional health and well-being has been examined significantly in cross-sectional research. Overwhelmingly, the literature has shown that food insecurity is related to higher levels of depression, stress and anxiety. For example, Hromi-Fiedler et al. reported over 2·5 higher odds of depression among pregnant food-insecure women compared with pregnant food-secure women( Reference Hromi-Fiedler, Bermúdez-Millán and Segura-Pérez 10 ), a finding which is supported by others( Reference Sharkey, Johnson and Dean 11 , Reference Feeny, McDonald and Posso 12 ). Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggest that food insecurity, but not poverty, is associated with higher rates of depression and even suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents( Reference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo 13 ). In a review of the twenty-seven qualitative and quantitative studies from developing nations, Weaver and Hadley reported that food insecurity is related to anxiety, shame, stress, resignation and depression( Reference Weaver and Hadley 14 ). However, a clear understanding on how food insecurity differentially impacts emotional well-being over time in the USA is needed. Food insecurity and emotional well-being may manifest differently in the USA, as access to public programmes and perceptions of health may vary from developing and other high-income nations.

Given that most of the research examining food insecurity and emotional health and well-being is cross-sectional, we need more insight into the causal mechanisms involved in the associations. By understanding the temporality, interventions can be better designed to assist those struggling. As such, the purpose of the present study was to conduct a systematic narrative review of the longitudinal literature assessing the relationship between food insecurity and emotional health and well-being. We limited our search to the USA to inform intervention work for those populations, differentiating the present review from the recent review conducted in developing nations( Reference Weaver and Hadley 14 ).

Methods

A systematic review of recent literature (January 2006–July 2016) was conducted to find articles that addressed food insecurity and emotional health over time. A combination of food insecurity and emotional health key terms (Table 1) was used to create a comprehensive list of articles from MEDLINE (PubMed), PsychInfo, Web of Science and CINHAL databases. English-language studies were screened for food insecurity and emotional health. Studies were included for review if they were observational or intervention studies, and if they had individual or household food insecurity measures, and any measure, positive or negative, of emotional health. Studies were limited to longitudinal designs conducted in the USA. Cross-sectional and qualitative studies were excluded.

Table 1 Food insecurity and emotional well-being key terms

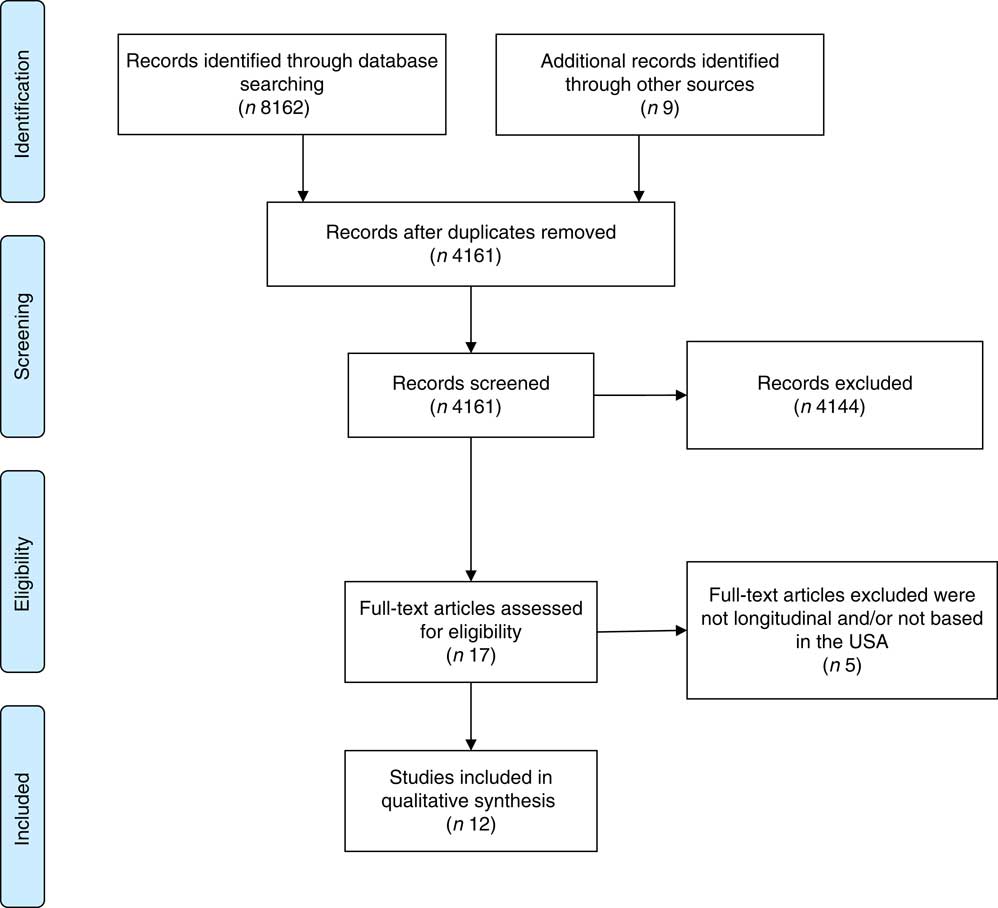

Articles were reviewed in the following order: title, abstract, methods and full manuscript. M.B. and L.M.D. reviewed all titles and abstracts and identified articles that met the inclusion criteria. J.B.R.C. reviewed all identified articles and settled disagreements between M.B. and L.M.D. Data extraction for each article meeting the inclusion criteria was completed by the three researchers independently and compared for full accuracy. Extracted data included: authors’ names, year of publication, data source, year of data collection, study time points used for the analysis, country of study, sample demographics, populations included in the study as stage of the life cycle, relevant food insecurity and emotional health measures, directionality of the relationships, outcomes related to food insecurity and emotional health, and limitations as identified by the author. The reference lists of articles meeting inclusion criteria were screened for additional studies. We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist for the systematic review.

Results

In total, after duplicates were removed, 4161 articles were screened at the title and abstract levels (see Fig. 1). Of these, only seventeen articles were screened at the full-text level. The present literature review includes the findings from twelve longitudinal studies assessing measures of food insecurity and emotional well-being (Table 2). While all but two of the twelve studies examined the longitudinal relationships between food insecurity and emotional well-being in households with children, only one study examined child emotional well-being outcomes( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ). Descriptions of measurements and data sources are included in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of peer-reviewed literature examining the longitudinal relationship between food insecurity and emotional well-being

Table 2 Data extraction of longitudinal US studies that examine the relationship between food insecurity (FI) and emotional well-being

NA, not available; FPL, federal poverty level; NH, non-Hispanic; AA, African American; HoH, head of household; USDA, US Department of Agriculture; HFSSM, Household Food Security Survey Module; HFS, Household Food Security; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; SF-36,36-Item Short Form Survey; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; aβ, adjusted β coefficient.

* Calculated from weighted averages.

† Adjusted estimate: indicates if models controlled for sociodemographics and/or other confounders.

Effect of emotional well-being on food insecurity

Three articles looked solely at the relationship between depression at baseline and food insecurity at follow-up( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 – Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ). All three measured food security status via the eighteen-item US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Survey Module (USDA HFSSM); although the measure for depression differed between the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) twenty-item scale( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 ), the CES-D twelve-item scale( Reference Garg, Toy and Tripodis 17 ) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF)( Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ). Among the three articles, samples of parents with young children were drawn from three different data sources( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 – Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ). The analyses by Hernandez et al. and Garg et al. focused exclusively on maternal depression( Reference Garg, Toy and Tripodis 17 , Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ) whereas Hanson and Olson examined depression among parents( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 ). The mean sample size among the three studies was 1611 (range: 225–2917).

Despite their different measures and samples, these three articles showed the same general outcome pattern: depression at baseline is associated with food insecurity at follow-up. To illustrate, Hernandez et al. found that households in which mothers experienced depression were twice as likely to experience food insecurity (OR=2·03; P<0·001) compared with households in which mothers did not experience depression( Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ). This relationship also remained after controlling for intimate partner violence (adjusted OR=1·97; P<0·001)( Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 ). Similarly, in the article by Garg et al. maternal depression at baseline predicted household food insecurity at follow-up (adjusted OR=1·50, 95 % CI 1·06, 2·12) after controlling for sociodemographics and maternal self-reported health status( Reference Garg, Toy and Tripodis 17 ).

In the article by Hanson and Olson, compared with respondents having no years at risk for depression, respondents with 2 years of depression risk were significantly more likely to have persistent food insecurity (food insecurity for three straight years) than to have no food insecurity (OR=4·28; P<0·01) or discontinuous food insecurity (food insecurity for 1 or 2 years, OR=3·65; P<0·05)( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 ).

Effect of food insecurity on emotional well-being

Five studies hypothesized that food insecurity was a factor driving emotional well-being( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 – Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). The populations examined in these analyses covered virtually all periods of the life course, from pregnancy/postpartum, toddlers and adolescents to the elderly( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 – Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). The mean sample size for these analyses was 4755 (range: 416–9481). The most commonly used tool to measure food insecurity was the USDA HFSSM( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 , Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 , Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). Other food insecurity measures included the Core Food Security Module( Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 ) and questionnaires generated by investigators( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ).

For emotional well-being, most studies measured the mothers’ depression levels( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 , Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 ). Several studies examined anxiety( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ) and stress( Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 , Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). Two studies also included measures for children’s emotional well-being by measuring the children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviours( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). Internalizing behaviours included withdrawn or sad behaviours, and externalizing behaviours included aggressive behaviours such as disobedience, anger and defiance( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). Emotional health was measured using a wide variety of tools: CES-D eight-item scale( Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 ); CES-D twenty-item scale( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 ); Child Behavior Checklist for anxiety/depression, withdrawn and aggressive subscales for mothers and children( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ); ten-item Perceived Stress Scale( Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 ); Emotional Wellbeing: Toddler Attachment Sort-45( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 ); and the thirty-two-item Behavior Problem Index for internalizing and externalizing behaviours( Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ).

Each study drew samples of adults and children from different sources: Health and Retirement Study (HRS)( Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 ); Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD)( Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 ); Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study (FFCWB)( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ); Pregnancy, Infection and Nutrition (PIN) study( Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 ); Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B)( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 ); and Child Development Supplement (CDS) to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID)( Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ).

The overall results supporting the hypothesis that food insecurity drives depression levels were mixed. Over half (60 %) of the studies found that food insecurity at baseline is associated with emotional health at follow-up( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 – Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 ). This can be illustrated by Laraia et al., who found that women who were exposed to any level of food insecurity during pregnancy and postpartum had high levels of perceived stress at 3 and 12 months postpartum (β=3·36, 95 % CI 0·79, 5·92; β=3·67, 95 % CI 0·94, 6·41, respectively)( Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 ). Likewise, Kim and Frongillo found that among one group of younger elders (mean age=60·8 years), those who were food insecure were more likely to show signs of depression compared with those who were food secure (β=0·16; P<0·013); however, among a population of older elders (mean age=79·6 years), the relationship was not significant (β=0·15; P=0·185)( Reference Kim and Frongillo 20 ). Household food insecurity was also associated with subsequent maternal depression (adjusted β=0·183; P<0·001) and was mediated by positive parenting practices( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 ).

In the remaining studies, the association between food insecurity and subsequent emotional well-being was null or was lost after adjusting for additional variables( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 , Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ). For instance, Zilanawala and Pilkauskas found in their cross-sectional analysis that food insecurity was positively associated with children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviours, but longitudinally this association did not persist( Reference Zilanawala and Pilkauskas 15 ). Huang et al. also reported that food insecurity was associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviours, but after adjusting for parental characteristics, the relationship was no longer statistically significant( Reference Huang, Matta Oshima and Kim 22 ).

Bidirectional effect of food insecurity and emotional well-being

Four articles examined the bidirectional relationship between emotional well-being and food insecurity( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). Three of these studies examined maternal populations( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ), and the last examined HIV-infected homeless people in San Francisco( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). All four studies examined depression using the CES-D( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ) or the Beck Depression Inventory( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). One study also examined overall mental health( Reference Lent, Petrovic and Swanson 24 ); the three studies that used the CES-D assessed maternal depression( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ). Food insecurity was determined with the USDA HFSSM in three studies( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ), while one study measured food insecurity with the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). The sample size in these studies was in the range of 29–346 with a mean sample size of 218.

Huddleston-Casas et al. examined non-imputed and imputed relationships. In the non-imputed findings, time 1 food insecurity was not significantly related to time 2 depression (β=0·077; P=0·132), but time 1 depression was significantly related to time 2 food insecurity (β=0·212; P<0·001)( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 ). In imputed models, both the relationship between food insecurity and subsequent depression (β=0·082; P=0·023) and the relationship between depression and subsequent food insecurity were found to be statistically significant (β=0·193; P<0·001)( Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 ).

Lent et al. reported that lower mental health scores at time 2 were significantly related to food insecurity at time 3 (P=0·01)( Reference Lent, Petrovic and Swanson 24 ). Post hoc χ 2 analyses showed a non-significant relationship between food insecurity and continuation of depressive symptoms at time 3 among the participants who scored at risk of depression at time 1 (P=0·62)( Reference Lent, Petrovic and Swanson 24 ). Doudna et al. also examined food insecurity and emotional well-being across two time periods( Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ). The results from their study indicated statistically significant associations between food insecurity at time 1 predicting time 2 depressive symptoms (β=0·221; P<0·001), and depressive symptoms at time 1 predicting time 2 food insecurity (β=0·116; P=0·027)( Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ). These authors also examined how community resources may have mediated the bidirectional models, and found that knowledge of community resources was not protective in either relationship( Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 ). Finally, Palar et al. examined the bidirectional relationship between the severity of food insecurity (mild v. moderate v. severe food insecurity) and depression( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). Moderate and severe food insecurity were significantly related to higher depression scores and greater odds of depression later, after adjusting for time 1 depression (P<0·01)( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). In lagged models to control for the potential of reverse causality, only severe food insecurity was associated with depression (P<0·001), suggesting possible reverse causality for mild and moderate food insecurity and depression severity( Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ).

Discussion

The majority of studies included in the present review show significant associations between poor mental health and food insecurity, and suggest a bidirectional association whereby food insecurity increases the risk of poor emotional health, and poor emotional health increases the risk of food insecurity. Two-thirds (66·7 %) of the nine studies assessing food insecurity at baseline found positive associations with poor emotional health at follow-up( Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps 19 – Reference Laraia, Vinikoor-Imler and Siega-Riz 21 , Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 , Reference Doudna, Reina and Greder 25 , Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ). Likewise, 100 % of the seven studies measuring poor emotional health at baseline showed positive associations with food insecurity at follow-up( Reference Hanson and Olson 16 – Reference Hernandez, Marshall and Mineo 18 , Reference Huddleston-Casas, Charnigo and Simmons 23 – Reference Palar, Kushel and Frongillo 26 ).

These findings, while perhaps not surprising, are indeed alarming. Poor emotional health is an adverse outcome within itself and greatly impacts quality of life. Independently, poor emotional health can lead to poor physical health outcomes, including CVD, type 2 diabetes, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, physical disability, unintentional and intentional injury, impaired child growth and development, and infant mortality( Reference Prince, Patel and Saxena 27 ). Similarly, food insecurity has been associated with asthma, anaemia, birth defects, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, poor sleep outcomes and oral health problems( Reference Gundersen and Ziliak 28 ). When both poor emotional health and food insecurity are experienced by the same individual, these effects on physical health may be interactive and multiplicative. It is therefore necessary to identify those individuals, families and communities that are at risk for poor emotional health, food insecurity, or both. For example, federally funded food programmes such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) – whose purpose is to help lift Americans out of food insecurity – can also promote mental and emotional well-being through social marketing campaigns and messaging, screenings and referrals. In fact, some WIC programmes in California and Washington, DC have already successfully integrated postpartum depression screening and referrals into their nutrition intake and assessment protocol( Reference Pooler, Perry and Ghandour 29 , Reference Fritz 30 ). The prevention of poverty and other efforts to address materially impoverished conditions among at-risk groups would likely improve both food insecurity and emotional well-being.

Conversely, physicians, mental health professionals, social workers, registered dietitians and hospitals should include individual and household food security screenings as part of their intake and admissions protocol. Hager et al. have validated a two-item food security screening tool that can serve as a quick and easy screen for food insecurity risk among low-income families with young children, which has subsequently been used and validated in adults and youth( Reference Baer, Scherer and Fleegler 31 , Reference Gundersen, Engelhard and Crumbaugh 32 ). It is important that positive screening is followed with an appropriate intervention. For patients with a positive screen, health-care professionals can then make appropriate and timely referrals to federally funded food programmes that patients may be eligible for, including SNAP, WIC, school meals programmes, and local pantries and soup kitchens. Additionally, hospitals can conduct on-site SNAP enrolment, serve as a WIC site, operate food pantries and summer meals programmes, and offer access to fresh fruits and vegetables via farmers’ markets and hospital gardens( 33 ). Intervention studies are needed to assess if programmes addressing food insecurity improve mental health and vice versa. Research on the long-term additive effect of food insecurity and poor emotional well-being on quality of life and interpersonal relationships is also needed. To support this study and the study among low-income countries( Reference Weaver and Hadley 14 ), similar studies are needed across more middle-income countries.

Despite the consistent patterns found among most of the studies reviewed, a few limitations that should be noted. First, several studies included small or homogeneous samples, limiting generalizability within studies. However, across the twelve studies, sample sizes ranged from 29 to 9481, and samples varied by age and geographic location within the USA. It is important to note that many of the studies included in the present review were secondary data analyses, and therefore were not designed to rigorously examine the relationships between food insecurity and emotional well-being. Most of these studies examined maternal populations. As such, we need a better understanding of how food insecurity and emotional health impact other populations such as children and older adults. Often, in those studies where the relationship between food insecurity and emotional well-being was of primary interest, the studies were small and may have been underpowered. Despite this, the results were consistent across populations and across study design limitations. Additionally, we limited our search to the past 10 years to gain an understanding of the relationships post-recession; there may be additional relevant studies conducted prior to this period. Another limitation lies in the large number of measurement tools and outcome measures analysed by the studies, which unfortunately does not allow for meta-analysis. For example, while food insecurity was most commonly measured by the USDA HFSSM, some studies determined food hardship or hunger using different instruments. Similarly, emotional health outcomes included depression, anxiety and perceived stress, among others, and each of these outcomes was measured with several different scales. Such diversity in outcomes and measures makes it difficult to compare findings across studies. Still, trends in the longitudinal associations between poor emotional health and food insecurity (and vice versa) appear consistent regardless of these differences.

Notably, all twelve studies focused on the association between food insecurity and negative emotional health outcomes (depression, stress, anxiety, etc.). Despite our range of emotional health search terms, not one study meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria measured positive emotional health outcomes, such as happiness, satisfaction or contentment. While it may be assumed from the current review that these emotions would be inversely associated with food insecurity, there is a need for research to study these relationships. Focusing solely on negative emotions overlooks the potential for building on strengths and resiliency of the populations being studied. Conversely, other phenomena that may impact the health and well-being of populations struggling with food insecurity, such as racism, discrimination, abuse, stigma and social support, are worth exploring.

Conclusions

The present systematic narrative review identified a bidirectional relationship between poor mental health and food insecurity. Public health practitioners addressing mental health may consider screening for food insecurity for at-risk populations and vice versa. Better-constructed studies are needed to follow cohorts at risk for both food insecurity and poor emotional health to further understand the mediators and moderators of the relationships. Intervention studies designed to mitigate or reverse risks are also needed to determine best evidence for practice and policy.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose. Authorship: All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript. J.B.R.C. compiled the titles. All authors reviewed titles, abstracts and full-text articles. All authors were involved in the analysis and writing of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: As a systematic review, no new human subjects’ data were collected.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002221