With homelessness recognized as a growing problem in many developed countries, ‘the homeless’ have become an increasing focus of nutrition research and intervention. Problems of insufficient food access(Reference Antoniades and Tarasuk1–Reference Whitbeck, Chen and Johnson6) and nutritional vulnerability(Reference Cohen, Chapman and Burt7–Reference Wolgemuth, Myers-Williams, Johnson and Henseler15) have been documented among homeless groups in many affluent Western nations. Ethnographic research findings suggest that homeless individuals live a ‘hand to mouth’ existence, locked in a daily struggle to meet their immediate needs for food and shelter(Reference Dachner and Tarasuk16–Reference Wingert, Higgitt and Ristock18). Their nutritional vulnerability has been linked to the inadequacy of meals served in soup kitchens or shelters(Reference Burt, Aron, Douglas, Valente, Lee and Iwen2, Reference Cohen, Chapman and Burt7, Reference Darmon, Coupel, Deheeger and Briend8, Reference Johnson and McCool11, Reference Silliman and Wood19), but there has been little examination of the role of other food acquisition strategies.

In 2003, we undertook a study of 261 homeless youths in Toronto to characterize the extent and nature of their nutritional vulnerability(Reference Tarasuk, Dachner and Li14, Reference Gaetz, Tarasuk, Dachner and Kirkpatrick20, Reference Li, Dachner and Tarasuk21). Most youths interviewed existed outside the ‘social safety net’, obtaining money through the informal (and often illegal) economy and living in public spaces. Dietary assessments (results of which have been reported elsewhere) indicated that most had inadequate intakes of folate, vitamin A, vitamin C, Zn and Mg; additionally, more than half of the young women in the sample had inadequate intakes of Fe and vitamin B12(Reference Tarasuk, Dachner and Li14). Here we examine the relationship between chronic food deprivation and food acquisition practices among this sample to gain a fuller understanding of their vulnerability.

Methods

Sampling and data collection

Data collection occurred between April and October 2003. Youths were eligible to participate if they were: (i) 16–24 years of age; (ii) not pregnant; and (iii) without stable, secure housing arrangements, defined as having spent ten or more of the past thirty nights sleeping in a temporary shelter, indoor or outdoor public space, or friend’s place, because they had no place of their own. Six drop-in centres and twenty-eight outdoor locations where homeless youths ‘hung out’ (e.g. under bridges, in abandoned buildings, parks, garages) in downtown Toronto were identified as recruitment sites. Drop-in centre workers were contacted to obtain estimates of the number of eligible youths using their facilities, and field observations were conducted to estimate the number of homeless youths in each outdoor area. Quotas proportional to these estimates were developed for each site, assuming a target sample of 240 youths (120 male, 120 female). Because the number of homeless youths in any location at any time was relatively small, random sampling was not feasible. Instead, interviewers systematically approached each youth they encountered at each site. Of the 483 youths approached, 170 were deemed ineligible (68 % because they failed to meet the criteria for unstable housing, 24 % because they were over 24 years of age, 4 % because they were pregnant, 4 % for other reasons), forty declined to participate and twelve were subsequently dropped from the study (eleven because they were found to be duplicates and one because of data quality concerns). A final sample of 261 youths was achieved, reflecting an 83 % participation rate. Seventy per cent of the final sample was recruited from outdoor locations.

Participants were interviewed when recruited and the time and location for a second interview was arranged. One hundred and ninety-five participants (75 %) completed second interviews, and 91 % of these occurred within 14 d of the first interview. Both interviews included a multi-pass 24 h dietary intake recall, but the first interview also included an interviewer-administered questionnaire designed to capture sociodemographic characteristics, living circumstances over the past 30 d, frequency of alcohol and drug use over the past 30 d, food security, food acquisition strategies, and strategies used to obtain water to drink. Food security was assessed using the 30-d Food Security Module and a 6-month measure adapted from the Household Food Security Survey Module(Reference Bickel, Nord, Price, Hamilton and Cook22).

From a review of earlier studies of homeless youths in Canada(Reference Dachner and Tarasuk16, Reference Hagan and McCarthy17, Reference Gaetz and O’Grady23–Reference McCarthy and Hagan26), we identified five means of food acquisition common among this group: (i) purchasing food with money obtained through activities like panhandling; (ii) obtaining food from other people (passers-by or those with whom they had some relationship); (iii) obtaining food free of charge or at nominal cost from charitable meal programmes; (iv) stealing food; and (v) retrieving food that had been discarded by others. To characterize participants’ use of charitable meal programmes, we asked how often in the past 7 d they had obtained meals from a soup kitchen, drop-in centre, shelter or mobile van (the primary routes through which food assistance is dispensed to homeless individuals in Toronto). To determine their use of other strategies, we developed a series of closed-ended questions to ask how often over the past 30 d they had engaged in specific activities to get food when they had no food or money for food; frequency was recorded as ‘never, ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’. The questionnaire was pilot-tested on a sample of twenty-five homeless youths to ensure the acceptability and comprehensibility of all items.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS/PC statistical software package version 9·1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

To classify food security status over 6 months, we applied the thresholds used to classify adult food insecurity in US population surveys(Reference Bickel, Nord, Price, Hamilton and Cook22, Reference Nord, Andrews and Carlson27). Food security over the previous 30 d was assessed in terms of chronic food deprivation, defined as reporting three or more of five conditions (i.e. skipped meals, ate less than you felt you should, felt hungry but did not eat, cut the size of meals, went a whole day without eating) for ≥10 d during this period.

Logistic regression was used to compare food security prevalence rates by gender and identify personal characteristics associated with chronic food deprivation over the past 30 d, considering age (<19 years, ≥19 years), duration of homelessness (<1 year, ≥1 year), education (completion of grade 12 or not), frequent drug use (defined as using crack, cocaine, speed/crystal, opiates, glue, gasoline, tranquilizers, hallucinogens or ecstasy every day or several times per week) over the past 30 d, and consumption of alcohol every day or several times per week over the past 30 d. Logistic regression was also used to examine the association between chronic food deprivation and reported problems obtaining water to drink, the frequency of programme use (considering both rare (≤2 d) and frequent (6–7 d) use over the past 7 d) and the frequent use of other specific food acquisition strategies (defined as ‘often’ using the strategy in the past 30 d). Because youths’ food acquisition patterns and experiences of chronic food deprivation differed by gender, all analyses were stratified.

Results

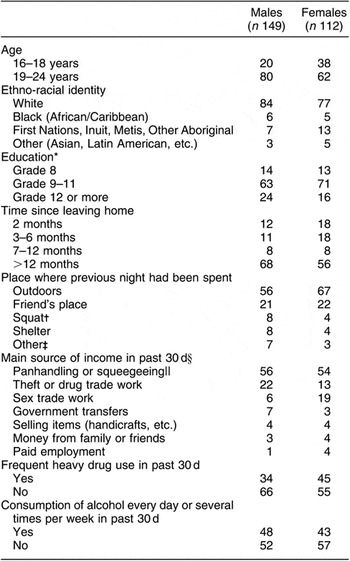

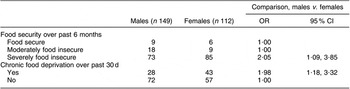

Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Almost all youths were food-insecure over the past 6 months and most experienced severe food insecurity (Table 2). Over the past 30 d, 43 % of females and 28 % of males experienced chronic food deprivation. Severe food insecurity and chronic food deprivation were more prevalent among females.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics and present circumstances (%): homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

*Generally, youths in Canada complete Grade 12 at the age of 18 years.

†‘Squats’ are makeshift shelters in abandoned buildings.

‡Included jail, Internet café, bath house, hotel, ‘with client’ and ‘own place’.

§Two males reported no source of income.

||The practice of washing the windows of vehicles stopped at intersections and then asking motorists for money.

Table 2 Food security status over past 6 months and past 30 d (%): homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

Chronic food deprivation appeared unrelated to youths’ age or education level (data not shown). There was also no relationship between the duration of homelessness and chronic food deprivation among males (OR = 1·59, 95 % CI 0·77, 3·38), but the odds of chronic food deprivation among females who had been homeless for a year or more was 2·87 (95 % CI 1·32, 6·23) compared with those who became homeless more recently. Females who reported consuming alcohol daily or almost daily had higher odds of chronic food deprivation (OR = 2·26, 95 % CI 1·05, 4·86), but no similar association was observed for males (OR = 1·39, 95 % CI 0·68, 2·87). Frequent heavy drug use was not associated with chronic food deprivation (males: OR = 1·15, 95 % CI 0·55, 2·45; females: OR = 0·81, 95 % CI 0·38, 1·72).

Thirty-two per cent of females and 48 % of males reported problems obtaining drinking water. For males, this was positively associated with chronic food deprivation (OR = 2·13, 95 % CI 1·01, 4·51), but no significant association was observed for females (OR = 1·46, 95 % CI 0·69, 3·11). The most commonly reported sources of drinking water were fast-food restaurants and washrooms (Table 3).

Table 3 Reported sources of drinking waterFootnote *: homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

* Because respondents could report more than one source, values do not add to 100 %.

† Data missing for one female.

Relationship between chronic food deprivation and food acquisition strategies

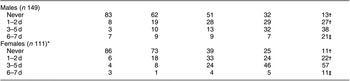

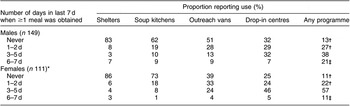

In the past 7 d, 87 % of males and 89 % of females had made at least some use of charitable meal programmes, with drop-in centres the most common source of meals (Table 4). The frequency with which youths used meal programmes was unrelated to their experiences of chronic food deprivation.

Table 4 Frequency of meal acquisition from charitable food assistance programmes over past 7 d: homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

*Missing responses for one female.

†The odds of chronic food deprivation in the past 30 d for youths who used programmes 0–2 d was 1·85 (95 % CI 0·70, 4·89) for males and 0·33 (95 % CI 0·09, 1·18) for females, compared with other youths.

‡The odds of chronic food deprivation in the past 30 d for youths who used programmes 6–7 d was 0·54 (95 % CI 0·21, 1·43) for males and 3·00 (95 % CI 0·85, 10·6) for females, compared with other youths.

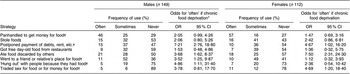

When they needed food over the past 30 d, almost three-quarters of youths panhandled and about half stole food, but neither strategy was associated with chronic food deprivation for males or females (Table 5). Over the past 30 d, 44 % of males and 47 % of females had borrowed money from someone to buy food; the median amount of money borrowed was CAN$ 15·00. The behaviour was associated with chronic food deprivation for females (OR = 2·18, 95 % CI 1·02, 4·68), but not males (OR = 2·01, 95 % CI 0·97, 4·16). Further indication of the pervasive vulnerability associated with indebtedness came from youths’ reports of putting off paying for other things as a way to free up money for food. Almost half reported such behaviours in the past 30 d, and youths who often postponed payments had significantly higher odds of chronic food deprivation (Table 5).

Table 5 Use of food acquisition strategies over past 30 d: homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

*Odds ratio of reporting often using strategy, if classified as having experienced chronic food deprivation over past 30 d.

†Missing data for one male.

‡Missing data for one female.

Approximately half of the youths surveyed had eaten food discarded by others, and almost half reported getting free day-old food from fast-food establishments at some point in the last 30 d. The latter strategy was not linked to chronic food deprivation but, for both males and females, the odds of reporting often eating discarded food increased if they had experienced chronic food deprivation over this same period (Table 5).

At times when they needed food, it was not uncommon for youths to seek out the company of others who could provide it. Approximately half of the youths reported going to a friend or relative’s place to eat, and one-quarter of youths reporting ‘hanging out’ with people just because they had food (Table 5). The frequent use of these strategies was associated with chronic food deprivation for males but not females. Eleven per cent of males and 23 % of females had exchanged sex for food or money for food in the past 30 d, but the frequent use of this strategy was associated with chronic food deprivation only among females (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study of homeless youths was undertaken to characterize the extent and nature of their nutritional vulnerability. The portrayal of food insecurity that emerges from our research differs markedly from the phenomenon commonly assessed among domiciled groups. The youths reported much higher levels of food deprivation than are typically observed in general population surveys(28), highlighting the extreme vulnerability that comes with homelessness and the abject poverty that underscores this condition.

In addition to problems of food deprivation, many youths reported problems accessing drinking water. Similar findings emerged from a recent study of street-based sex workers in Miami(Reference Kurtz, Surratt, Kiley and Inciardi29). Without housing and with insufficient funds to purchase bottled water, homeless people are forced to rely on public sources of water or negotiate access to private supplies. In urban settings such as Toronto, access to public washrooms and drinking fountains has become increasingly limited because of concerns about cost and liability. Thus inadequate and insecure access to drinking water is an added dimension of food insecurity among homeless populations.

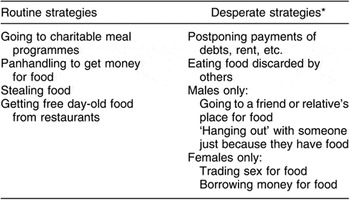

The ways in which homeless youths endeavoured to manage their food needs reflect a ‘hand to mouth’ existence, characterized by the use of a wide diversity of strategies to obtain small amounts of food for immediate consumption. Many of these strategies were stigmatizing and unsafe; some were illegal. Our examination of the relationship between youths’ use of specific food acquisition strategies and their level of food deprivation suggests that some strategies such as eating food discarded by others are acts of extreme desperation, whereas other behaviours like panhandling and stealing food are routine (Table 6). Although other researchers have not differentiated homeless youths’ food acquisition behaviours in this way, the fact that similar behaviours have been reported by others(Reference Hagan and McCarthy17, Reference Wingert, Higgitt and Ristock18, Reference McCarthy and Hagan26) suggests that our findings are characteristic of homeless youths in this country.

Table 6 Strategies employed to acquire food routinely or in times of desperation: homeless youths, Toronto, Canada, 2003

*Food acquisition strategies associated with significantly increased odds of chronic food deprivation over the past 30 d.

Although many youths in this study routinely used charitable meal programmes, this practice did not protect them from chronic food deprivation, nor did it obviate the need for them to acquire food in other ways as well. These findings highlight the need for a better ‘safety net’ to help youths meet their basic needs. In our qualitative research with homeless youths, they complained about the infrequent service, limited meal hours, and need to travel considerable distances to attend different charitable meal programmes at different times of the day or week(Reference Dachner and Tarasuk16, Reference Gaetz, Tarasuk, Dachner and Kirkpatrick20). Our subsequent inventory of local charitable food provisioning efforts (to be reported elsewhere) confirmed that meal services for those outside the shelter system are, for the most part, intermittent and uncoordinated, and the food served is generally of limited quantity and nutritional quality(Reference Tse and Tarasuk30). While the establishment of ad hoc, charitable food programmes for homeless individuals is a strong testament to community concern and resourcefulness, our research results argue strongly for a more coherent response.

Our examination of youths’ food acquisition strategies highlights the gendered nature of homelessness, a phenomenon documented elsewhere as well(Reference Khandor and Mason5, Reference Gaetz24, Reference McCarthy and Hagan26, Reference Ensign and Bell31, Reference Roy, Haley, Lemire, Boivin, Leclerc and Vincelette32). Other research with street youths has found that males generally earn more than females and are more likely to operate independently, whereas females tend to engage collectively, both in money-making and in living arrangements(Reference Gaetz24). Consistent with this research, we found that using social relationships as a means to acquire food was routine for females, but such behaviour indicated desperation for males. None the less, female youths may engage more in high-risk, exploitive relationships, trading sex for food when they are desperate.

In conclusion, the pervasiveness and severity of food insecurity experienced by homeless youths in the present study and their desperate means of food acquisition highlight the urgent need for more effective responses to food insecurity among this group. While more work could be undertaken to improve youths’ food access through charitable meal programmes in the community, we worry that this would amount to ‘treating the symptom’ rather than the problem. Homeless youths’ food acquisition behaviours reflect the extreme desperation of their situations, providing a moral and public health imperative to find solutions to the problem of youth homelessness in Canadian cities.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). In receiving this funding, the authors did not engage in any financial or other contractual agreements that caused or could be perceived to cause conflicts of interest. None of the authors has any other conflicts of interest to declare. All authors participated in the conceptualization of the research questions and study design, and aided in the interpretation of the results. V.T. conducted the statistical analysis and developed the manuscript. The authors are indebted to Mark Nord for assistance with the food security measure and to Tony Jinguang Li for preliminary data analysis.