Obesity is extremely widespread in many different countries, regardless of the level of economic development(Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson1). Many external and internal factors are known to increase the risk of obesity in modern society. The main external factor is the easy availability of cheap, energy-dense foods (the so-called ‘obesogenic environment’)(Reference Corsica and Hood2). Food addiction (FA) appears to represent one of the internal risk factors for obesity(Reference Volkow and Wise3). The concept of FA is based on the assumption that certain foods, such as high-energy(Reference Pursey, Collins and Stanwell4), fatty, high-sugar(Reference Ayaz, Nergiz-Unal and Dedebayraktar5), hyperpalatable(Reference Gearhardt, Davis and Kuschner6) and/or highly processed foods(Reference Schulte, Avena and Gearhardt7), can cause changes in eating behaviour. People with FA(Reference Gold, Frost-Pineda and Jacobs8) cannot control the consumption of problematic foods and continue to consume them despite the negative physical or emotional consequences. Reports of FA have been shown to be particularly high among overweight/obese people(Reference Gearhardt, White and Masheb9–Reference Gearhardt, Boswell and White11) and individuals who engage in emotional eating(Reference Gearhardt, Roberto and Seamans10,Reference Manzoni, Rossi and Pietrabissa12) . Numerous studies have noted the close relationship between FA and depression(Reference Burmeister, Hinman and Koball13–Reference Burrows, Kay-Lambkin and Pursey16). Some studies revealed associations among late chronotype, poor sleep quality and FA(Reference Kandeger, Selvi and Tanyer17,Reference Najem, Saber and Aoun18) .

It can be assumed that the risk of FA differs in different groups of the population due to the different sociocultural pressures from the obesogenic environment to which these groups are exposed. Causal mechanisms of the relationship between FA and excessive body weight can differ depending on the age. It was previously shown that the FA detection rate shows a significant increase in 17–18-year-old adolescents and reaches maximum values in individuals at the age of 19–20 years(Reference Borisenkov, Popov and Tserne19). Possible reasons for these changes in eating behaviour are significant increases in academic workload caused by preparation for final exams and lifestyle changes caused by starting a life apart from parents. Increased workload, pressure for success, separation from home and post-school plans are sources of stress, anxiety and depression(Reference Beiter, Nash and McCrady20,Reference Farrer, Gulliver and Bennett21) leading to eating disorders such as dietary restraint and binge eating among students(Reference Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner22). Therefore, comparing factors associated with FA among schoolchildren and university students is of great interest.

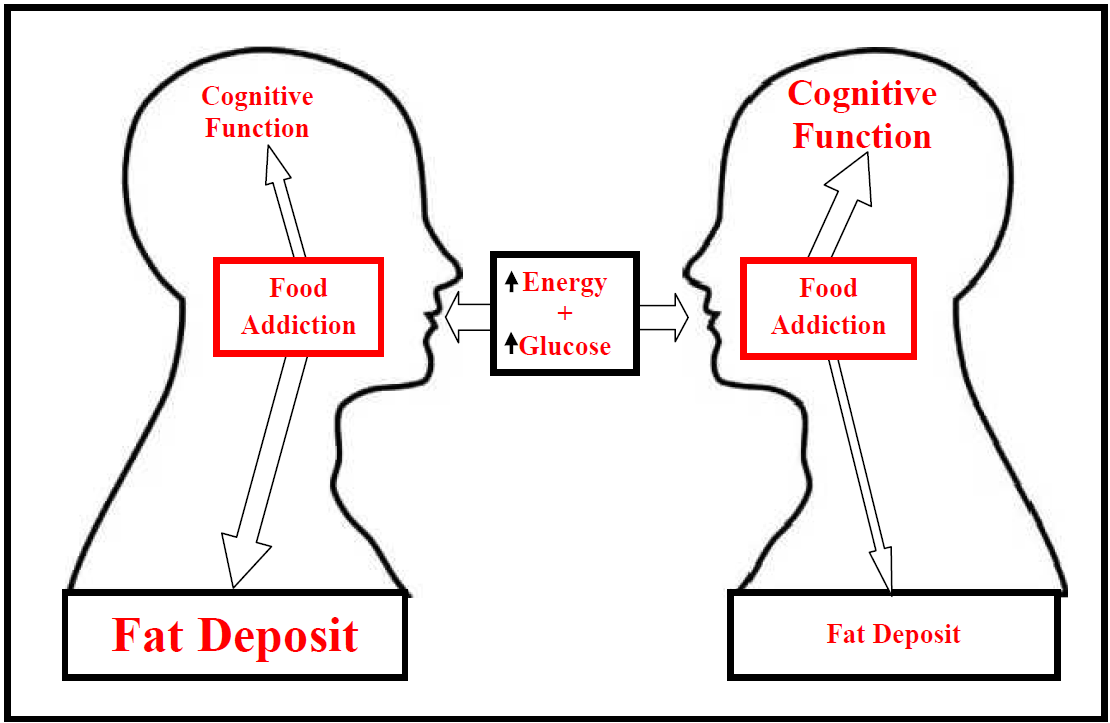

Mental activity and its energy supply have some important features. First, mental activity is a highly energetically expensive process. The brain makes up 2 % of the body weight but consumes 20 % of the available energy at rest(Reference Müller and Geisler23). Second, glucose is the main source of energy for brain function(Reference Benton, Parker and Donohoe24). These two characteristics of mental activity and energy supply overlap with some of the characteristics of eating behaviour in individuals with FA. According to the recent data(Reference Pursey, Collins and Stanwell4,Reference Schulte, Avena and Gearhardt7,Reference Burrows, Hides and Brown25) , high-energy foods rich in carbohydrates and fats predominate in the diet of individuals with FA.

It is known that obesity in humans is associated with suppressed cognitive function(Reference Smith, Hay and Campbell26); obese children show reduced executive function, including a worse working memory, and reduced problem-solving abilities, inhibitory control, flexible thinking and planning ability. These functions are critically important for academic performance(Reference Best, Miller and Naglieri27). Therefore, a negative relationship between successful mental work and BMI is expected, and a positive relationship between FA and BMI has been observed(Reference Borisenkov, Tserne and Bakutova15).

To our knowledge, no studies investigating the relationship between FA and BMI have been conducted in people who engage in intensive mental work. Only a few studies of FA and BMI in schoolchildren and students have been undertaken(Reference Pursey, Collins and Stanwell4,Reference Borisenkov, Tserne and Bakutova15,Reference Ahmed and Sayed28,Reference Ahmed, Sayed and Mostafa29) , none of which considered the relationships between these indicators and academic performance. A number of studies have reported no association, or only a weak association between FA and BMI(Reference Gearhardt, Yokum and Orr30–Reference Meule and Kübler32). Some authors(Reference Gearhardt, Yokum and Orr30) have attributed the presence of FA in individuals without signs of obesity to the fact that the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) allows for the detection of FA in individuals before the appearance of body weight disorders. However, the weak association between FA and BMI may be due, in part, to the influence of intense mental work.

The purpose of this study was to compare the frequency of detection of FA in schoolchildren and university students from India and Russia and to test the hypothesis that people engaged in mental work have an increased frequency of detection of FA without signs of obesity. The subjects of this study were schoolchildren and students. The intensity of mental work in the study participants was assessed by academic performance. FA was assessed using the YFAS, and body composition was assessed by BMI.

Methods

Study participants

The study involved the voluntary and anonymous participation of 3426 schoolchildren and university students from Russia and India. In Russia, the study was conducted between May 2017 and December 2019. Schoolchildren were informed of the study via school psychologists, and university students were informed via university professors and received course credit for completing the study. The study included 1212 schoolchildren from fourteen secondary schools in Syktyvkar and 1350 students from universities located in four cities. A total of 277 (12·8 %) questionnaires filled out with errors or omissions were excluded from the analysis. Participants were healthy individuals who gave verbal informed consent to participate in the study. Verbal informed parental consent was obtained from the parents of schoolchildren. Secondary-school students filled out paper questionnaires, and university students filled out a battery of tests online.

In India, the study involved schoolchildren from five secondary/higher secondary schools and students at the University of Mizoram, all situated in Aizawl city. The study was conducted between June 2018 and October 2019. Schoolchildren were informed of the study via school teachers, and university students were informed via university professors. The study included 427 school students (9th–12th grades) and 437 university students (postgraduate students). 87·2 % of participants from India belonged to the Mizo ethnic group. All the participants were informed about the objectives of the study, and consent was obtained from the participants and, for the school students, their parents. Short characteristics of the settlements are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Short characteristic of settlements

Lat., latitude; Long., longitude; ln(population), natural logarithm of population.

Measures

Each study participant indicated their age, sex, height and weight; provided information on their academic performance; and also completed the YFAS. Some of the study participants also completed the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Self-reported height and weight values were used to calculate BMI. Four BMI categories (BMIc) of individuals were identified according to WHO criteria(33) as follows: underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese. The average values of the measured indicators of the study participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Characteristics of study participants

SC, symptom counts; FA, food addiction.

Academic performance

To assess academic performance, all Russian participants were asked the following question: ‘What was your average grade (GPA) for the quarter/session preceding the study?’ The reliability students’ academic performance records were checked as described in Supplementary Material. We then assigned each participant’s raw GPA score to either a low (GPAL), average (GPAM) or high (GPAH) category. In Russia, a unified grading system for schoolchildren and university students is used; therefore, scores were assigned to categories according to the following scheme: GPAL = a score of 3–3·5, GPAM = 3·6–4·5 and GPAH = 4·6–5.

In India, academic performance was assessed in terms of cumulate GPA. Students’ academic records were verified with school/university records. Because different grading systems are used for schoolchildren and university students, we converted the raw GPA scores of schoolchildren and university students separately into three categories as follows: for schoolchildren, GPAL = a score ≤7·7, GPAM = 7·8–8·9 and GPAH = ≥9; for university students: GPAL = a score of 5–6·7, GPAM = 6·8–7·9 scores and GPAH = ≥8.

Food addiction

The YFAS(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell34) and YFAS for children (YFAS-C)(Reference Gearhardt, Roberto and Seamans10) were used to evaluate the incidence of FA in young adults and adolescents aged <18 years, respectively. The YFAS provides the following two scoring options: the symptom count, which is equal to the sum of confirmed symptoms (range, 0–7); and a dichotomous measure of FA. The Russian study participants filled out questionnaires that were translated into Russian. Brief psychometric descriptions of the YFAS-Rus(Reference Borisenkov, Popov and Pecherkina35) and YFAS-C-Rus(Reference Borisenkov, Tserne and Bakutova15) are published. Schoolchildren and university students in India are fluent in English, so the original version of the YFAS was used to assess the incidence of FA in Indian study participants. Cronbach’s α for this sample was 0·846. The validity of the data collected in India was confirmed by the existence of a significant association (logistic regression, n 236; OR: 1·88, 95 % CI 1·50, 3·07, P < 0·012) between FA and the Emotional Eating subscale of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire(Reference Van Strien, Frijters and Bergers36). A similar association has been previously described(Reference Gearhardt, Roberto and Seamans10,Reference Borisenkov, Popov and Pecherkina35) .

Statistical analyses

The sample size necessary and sufficient to obtain reliable results was estimated based on the rule for qualitative analyses(Reference Schreiber, Nora and Stage37), according to which there should be at least ten people per studied parameter. In our case, ten analyses were planned, each of which had one dependent variable and six independent variables. Thus, the sample size should be at least 700 people.

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationships between the studied indicators. In the first model, ‘FA’ (Codes: 0 = No FA, 1 = FA) was specified as the dependent variable and sex (Codes: 0 = males, 1 = females), age, BMIc, country (Codes: 0 = Russia, 1 = India), latitude and ln(population) were specified as independent variables. In the second model, ‘GPA’ (Codes: 0 = GPAL + GPAM, 1 = GPAH) was specified as the dependent variable and the factors listed in Tables 1 and 2 were specified as independent variables. The code ‘0’ was used in both models as the comparison group. Only significant factors were included in the final models. We assessed multicollinearity among the predictor variables via the variation inflation factor. Predictors were excluded from the analysis if the variation inflation factor was ≥5. Based on this criterion, ‘latitude’ was excluded from the models.

Results

FA was identified in 14·6 % of the study participants from India. The average number (sd) of FA symptoms was 3·4 (s d 1·5). In Russia, FA was detected in 8·7 % of the study participants and the average number of FA symptoms was 2·1 (s d 1·6) (Table 2). According to the logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for related factors, the incidence of FA in schoolchildren and university students from India was twice as high as that in their peers from Russia (model 1, Table 3). In addition to the country of residence, the frequency of FA detection was significantly and positively associated with age, sex, BMI and the population of the city in which the study was conducted (model 1, Table 3).

Table 3 Results of logistic regression analyses*

β, regression coefficients; FA, food addiction; GPA, academic performance; ln(population), natural logarithm of population.

* Two series of binary logistic regression analyses were performed.

† In the model 1, we used ‘FA’ (Codes: 0 – No FA; 1 – FA) as dependent variable, ‘sex’ (Codes: 0 – males, 1 – females), ‘age’, ‘BMIc’, ‘country’ (Codes: 0 – Russia, 1 – India), ‘In(population)’ as independent variables; in models 1a and 1b, the same analyses were repeated as in model 1, on the group of schoolchildren and university students separately, respectively; in the model 2, we used ‘GPA’ (Codes: 0 – GPAL + GPAM, 1 – GPAH) was specified as dependent variable, factors listed in Tables 1 and 2 were specified as independent variables; in models 2a and 2b, the same analyses were repeated as in model 2, on the group of schoolchildren and university students separately, respectively.

‡ Code ‘0’ is used in the models as a ‘group of comparison’.

§ Only significant factors were included in the final model.

According to the logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for related indicators, the frequency of FA detection among Russian university students was 3·5 higher than in schoolchildren (OR = 3·50, 95 % CI 2·47, 4·97, P < 0·0001), and 1·9 times higher in Indian university students than in schoolchildren (OR = 1·86, 95 % CI 1·26, 2·74, P < 0·002) (data not shown in Table).

An analysis of factors associated with FA among the schoolchildren and university students separately (models 1a and 1b, respectively; Table 3) showed that in both cases, FA was associated with BMI and place of residence (higher in India). The schoolchildren also showed a positive association between FA and age, and the university students showed a positive association between FA and sex (higher in females) (models 1a and 1b, Table 3).

Academic performance in the combined sample was significantly higher in schoolchildren and university students living in large cities, women, persons with FA and persons without signs of being overweight or obese (model 2, Table 3, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Association between academic performance, incidence rate (%) of overweight/obesity (![]() , ov/ob) and food addiction (

, ov/ob) and food addiction (![]() , FA) in schoolchildren and university students

, FA) in schoolchildren and university students

An analysis of factors associated with GPA among the schoolchildren and university students separately (models 2a and 2b, respectively; Table 3) showed that only schoolchildren had a significant association between academic performance and FA and BMI.

Discussion

We noted a higher incidence of FA in overweight individuals and females. Data on the nature of the relationship between FA and the anthropometric and demographic characteristics of adolescents are consistent with the results of previous studies(Reference Meule31,Reference Mies, Treur and Larsen38) . We collected and analysed the data on the incidence of FA in schoolchildren and university students from India. Our findings showed that the frequency of FA detection in this population is 14·6 %. A comparative analysis showed that the incidence of FA in study participants from India is two times higher than in schoolchildren and university students from Russia.

Currently, there are two papers on the frequency of FA detection in residents of India(Reference Ghosh, Sarkar and Tilak39,Reference Wiedemann, Lawson and Cunningham40) . Ghosh and coauthors(Reference Ghosh, Sarkar and Tilak39) showed that the incidence rate of FA in 18–20-year-olds was 13·3 %, which practically coincides with our data. Wiedemann and coauthors(Reference Wiedemann, Lawson and Cunningham40) showed that the incidence of FA among Indian adults was 32·5 %. The reasons for these large differences in the data are unknown due to the limited number of studies carried out in India.

The association between the population size and the frequency of FA detection described in our study is of interest. These data are consistent with the view that the level of urbanisation is an independent risk factor for obesity(Reference Ogden, Fryar and Hales41). In large cities, high-energy foods are readily available, inexpensive and aggressively advertised in the media. All these factors, called the ‘obesogenic environment’(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza42), seem to have a stronger influence on urban residents, increasing the risk of developing FA and, as a consequence, obesity.

We have shown for the first time that there is an increased frequency of FA detection in adolescents with high academic performance. At the same time, a negative relationship was observed between academic performance and BMI. Thus, our findings support the hypothesis that people who exhibit a high academic performance have a combination of these two characteristics, reflecting the need of people engaged in intense mental work for high-energy foods that are rich in carbohydrates. A distinctive feature of high-performance individuals is normal or even low weight; obesity is known to inhibit human cognitive function(Reference Smith, Hay and Campbell26,Reference Best, Miller and Naglieri27) . A recent large meta-analytic review incorporating sixty studies with over 164 thousand participants revealed a mild, although significant, association between higher BMI and lower academic achievement(Reference He, Chen and Fan43). This relationship was significantly influenced by region and study grades. The review also proclaimed a need for further studies investigating factors that may potentially moderate this relationship.

Causal mechanisms of the relationship between cognitive function and excessive body weight can differ depending on the age(Reference Veit, Kullmann and Heni44). Structural brain changes in the prefrontal cortex(Reference Hamer and Batty45,Reference Laurent, Watts and Adise46) and diminished executive functions, such as working memory(Reference Laurent, Watts and Adise46), were found in adolescents and even in children with excessive body weight. BMI was most strongly associated with changes in orbitofrontal cortex areas, known to be involved in food choice and hedonic valuation(Reference Kringelbach47,Reference Volkow, Wang and Tomasi48) . Obesity-prone individuals have increased activation in the prefrontal cortical region and failed to show attenuation in the neuronal responses to food cues. In schoolchildren, obesity may differentially impact the attainments of girls and boys in certain disciplines, such as mathematics(Reference Martin, Booth and McGeown49).

Mental processes have been assumed to require physical energy and, therefore, would seem to decrease cognitive control(Reference Ampel, Muraven and McNay50). Impaired performance monitoring as a part of cognitive control has been previously found in people who meet the YFAS criteria for FA(Reference Franken, Nijs and Toes51). Therefore, the obtained data might suggest that adolescents with high academic performance find it more difficult to resist food temptations, possibly because intense mental work may deplete executive functions, including inhibitory control. In addition, intense academic activity by successful students may induce psychosocial distress. Emotional distress has been previously shown to be associated with loss of control eating(Reference Tanofsky-Kraff, Shomaker and Olsen52).

The age-related changes in the association between FA and GPA are probably explained by the fact that during the transition from secondary school to university, there is a selection of people who are psychologically more adapted to the educational process. Universities mainly enrol people who are more resistant to the effects of academic stress, in whom the stress factors of the educational process do not increase the risk of developing FA.

Strengths and limitations

This independent, multicentre study involving students from two countries located in different climatic and geographical areas of the Earth made it possible to evaluate the contributions of various external and internal factors to the frequency of FA detection in humans. There are some limitations in this study. First, the relatively small sample size we used in India does not allow us to confidently extend the study’s findings to the entire Indian population. In the future, it is necessary to study factors affecting the incidence rate of FA in the Indian population in more detail. Second, self-reported data on academic performance and anthropometric characteristics were used in this study, which significantly reduced the reliability of the results obtained. To avoid this limitation concerning academic performance, the results provided by the participants were cross-verified with the school/university records. Third, the cross-sectional design of this study did not allow us to evaluate causal relationships among the studied parameters.

Conclusion

A comparative analysis showed that the frequency of detection of FA in schoolchildren and university students from India is two times higher than in their peers from Russia. In two countries, the frequency of FA detection in university students was found to be higher than in schoolchildren. In the pooled sample, a positive relationship was found between the frequency of FA detection and academic performance and a negative relationship was found between BMI and academic performance. The data obtained suggest that more successful students find it more difficult to resist food temptations possibly because intense mental work may deplete executive function, including inhibitory control. On the other hand, more successful students are likely to be more organised and disciplined. In this case, the lack of cognitive control cannot explain their higher food dependence. Therefore, in the future, it is important to understand how successful and unsuccessful students differ in their cognitive control functions. Our findings are important, as they suggest that successful students are a vulnerable group that requires special attention given that modern society faces epidemic-like trends in obesity.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The YFAS scale and scoring instruction were kindly provided by Dr. Ashley Gearhardt. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: T.A.T.: conducting a survey. M.F.B.: designing the research, analysing the data, writing – original draft. S.V.P.: supervision, project administration. L.A.B.: data collection and analysis. L.J.: conducting a survey, data collection and analysis. A.K.T. supervision, data analysis. D.G.G.: supervision. A.A.P., O.I.D., E.A.M., V.I.V., S.V.S., L.A.D. and E.F.T.: conducting a survey. E.E.S. project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research participants were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Physiology, Komi Science Center the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Verbal informed consent was obtained from university students participated, and verbal informed parental consent was obtained from the parents of schoolchildren. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021002160