The nutrition and health transition

Thailand is one of several South-East Asian countries in transition from an agrarian to an industrial and post-industrial economy. Thai socio-economic change is increasing and international and local supermarket chains have integrated themselves into food retail at an unprecedented speed(Reference Kelly, Sleigh and Banwell1). A nutrition and health transition is underway with mortality, infectious diseases and undernutrition receding while low birth rates, overweight and obesity emerge(Reference Aekplakorn, Hogan and Chongsuvivatwong2). Thais are increasingly urbanized and profound changes in their diet include more sugar, oil, fats and animal meat and less vegetables and fruit(Reference Aekplakorn, Hogan and Chongsuvivatwong2–4). Between 1990 and 2008 the estimated daily energy intake per person in Thailand increased from 9414 to 10 627 kJ (2250 to 2540 kcal)(5) and over just two decades (1983–2006) sugar consumption almost tripled from 12·7 to 33·2 kg/person per year(4). Dietary changes, less physical activity due to urbanization, sedentary recreation and occupational changes(6, Reference Popkin7) are affecting body size.

Thai obesity has increased. The second (1997) and third (2004) National Health Surveys show that the age-standardized prevalence of adult obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) has increased from 25·6 % to 30·3 %(Reference Aekplakorn, Hogan and Chongsuvivatwong2). By 2009 obesity affected 40·7 % of women and 28·4 % of men(Reference Aekplakorn3). Population weight gain is more pronounced in urban areas and in the more economically developed Bangkok and the Central region, and lowest in the poorer North and North Eastern regions(Reference Aekplakorn3, 4). CVD, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, hormone-related cancers and gallbladder disease are all expected to surge(5). Considerable economic and social costs associated with obesity are anticipated, with implications for the health-care system(6). For example, in China and India the costs of obesity and related diseases will outstrip the costs of undernutrition in the next 25 years(Reference Popkin7).

The evolving food retail landscape

Thailand now stands out among other South-East Asian nations for its rapid growth in modern food retail outlets(Reference Mutebi8, Reference Shannon9). Traditionally, at fresh markets or night markets stallholders sold meat, fish, fresh vegetables, fruits and herbs(Reference Lefferts10, Reference Seubsman, Suttinan and Dixon11), and dry goods were bought from locally owned stores. Supermarkets, large self-service retail stores, first appeared in Bangkok in the 1960s(Reference Wigglesworth and Brotan12) and were followed there by an explosion in modern retail formats associated with a booming economy(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13). Later in 1989, 7-Eleven convenience stores arrived, located near commuter stops(Reference Tokrisna14).

With the 1997 financial crisis, partnerships between Thai and foreign firms were dissolved and the foreign partners took control. These transnational food companies proceeded to expand their operations; for example, from eighteen hypermarkets (defined as supermarkets with floor size of 15 000–20 000 m2)(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13) in 1996, to 148 a decade later. Their diffusion into regional centres occurred as rural incomes rose and rural people became more accustomed to urban-style living. The main companies were Tesco (UK), Carrefour (French) and Big C (French)(Reference Kanchoochat15), although Thailand's own CP (Chaoren Pokphand) group owns the 7-Eleven chain(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13) (the market leader in this category)(16) and the Siam Makkro chain. The rapid expansion of supermarkets and hypermarkets(Reference Tokrisna14, Reference Kanchoochat15), and the annual loss of about 25 000 small retailers(Reference Hawkes17), have closely paralleled Thailand's urbanization and industrialization.

Thailand's food retail system now consists of a traditional sector (fresh markets and ‘mom and pop’ stores) that caters to the ‘price sensitive’ and ‘traditional diet’ consumers(18) and a modern sector (hypermarkets, supermarkets and convenience stores) which has dominated the expansionary process since 2000(Reference Kuipers19). The modern retail sector has increased from about 35 % of market share in 1999 to 48 % in 2005(Reference Vandergeest20). In 1996, supermarkets, hypermarkets and convenience stores had 10·5 % of the retail food sales and by 2000 their share had increased to 18·4 %(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13). New legislation and regulations introduced in the 2000s have slowed the growth of foreign-owned supermarkets somewhat(Reference Shannon9). Nevertheless, super/hypermarkets are rapidly gaining ground with their number increasing from 110 in 1997 to 391 in 2007, alongside a sixfold growth in convenience stores(Reference Shannon9). This modern food retail growth has corresponded with a national decline in the number of fresh markets, falling from 160 to fifty in the past decade in Bangkok alone(Reference Sriangura and Sakseree21).

The growth of super/hypermarkets may have a role in the Thai nutrition transition through two mechanisms. First, it has implications for food affordability, particularly for the poorer 55 % of the population. In 2004, the average market basket of goods from a traditional market cost 9 % less than the equivalent basket of goods from the three major hypermarket retailers(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13). Recently, in Chiang Mai, it was observed that fresh produce at supermarkets cost between two and four times more than at fresh markets(Reference Isaacs22). Internationally, it is the wealthier, younger, urban middle class who tends to shop at supermarkets(Reference Gorton, Sauer and Supatpongkul23–Reference Figuié and Moustier25).

Second, supermarket expansion could influence food choice, weight and health. Hawkes(Reference Hawkes17) argues that supermarkets can be both positive by making ‘a more diverse diet available and accessible to more people – and negative – supermarkets can reduce the ability of marginalized populations to purchase a high-quality diet, and encourage the consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor, highly-processed foods’ (p. 657). They have an impact on the nutrition transition because overall ‘consumers eat more, whatever the food’(Reference Hawkes17). Currently, both healthy and unhealthy foods are available at supermarkets, fresh markets and other venues for urban Thais. However, small fresh produce providers may disappear as supermarkets drive out competitors and gain market share over time, leaving supermarkets to provide an abundance of cheaper processed foods and more expensive fresh foods.

Drawing on consumer and retailer views we discuss how Thai fresh markets are responding to the growth of supermarkets and what the potential outcomes of their expansion may be. Evidence suggests that the dynamics of the nutrition transition may be influenced, and the health and well-being of poorer Thais may be disproportionally affected.

Study methods

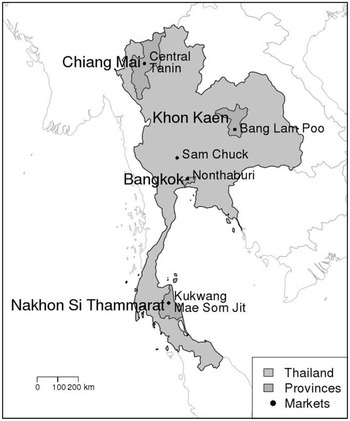

Fieldwork was undertaken progressively between 2006 and 2011 in seven fresh markets located in each of the North, North Eastern, Central and Southern regions (see Table 1 and Fig. 1), which represent major cultural, geographical, culinary and socio-cultural variation in Thailand. Central Thailand is the wealthiest area and the North Eastern or Isan area is the poorest(Reference Seubsman, Suttinan and Dixon11). The fresh markets were located in major regional centres (including the outskirts of Bangkok) and were selected to represent a variety of fresh market types, ranging from mainly retail to wholesale, renovated or not, and car or pedestrian focused.

Table 1 Fieldwork sites

Fig. 1 Map of Thailand showing fieldwork sites

The research team of eight people included bilingual Thai and Australian research assistants, a Thai nutrition epidemiologist, an Australian food sociologist and a medical anthropologist. The Thai assistants worked with local people in each city to set up the interviews and focus groups and were present at the markets. Each market was visited over a period extending from 1 to 4 d but not every team member was present at each market visit.

Rapid assessment procedures(Reference Manderson and Aaby26), consisting of a range of ethnographic research methods adapted for short-term fieldwork including the following, were used (Table 2).

Table 2 Fieldwork methods

Interviews were either (i) audio-recorded in Thai and later translated into English or (ii) Thai researchers provided translations while interviews were occurring which were then spoken into audio-recorders. Participants in focus groups and formal interviews were provided with food and drink. During opportunistic interviews (where prior arrangements had not been made for an interview), English-speaking and Thai researchers jointly interviewed participants and recorded responses in notebooks. The team met at the end of the day to discuss observations, photographs, findings and interpretations. Data were examined for common patterns of responses which were then integrated with researchers’ field notes of observations to identify major themes.

Results

Fresh markets under threat

Two markets in the Central region typify the impact of Thai economic and social trends on fresh markets. They illustrate how local communities and fresh market vendors cannot ignore the economic and cultural consequences of supermarket development.

Nonthaburi, 32 km from Bangkok, has always been farming land and its culture is rooted in home production with a well-established reputation for some of the best tropical fruit in the country. Now, construction sites are being built here as migrants working in Bangkok look for housing. Most farmers have sold their land, local orchards have disappeared, and vegetables and fruits from other provinces have replaced local products in the fresh market.

The Nonthaburi market was rundown and dirty and the Nonthaburi Municipal Office was keen to renovate it; however, renovating fresh markets causes considerable disruption to stallholders who lose their income while improvements are made. Stallholders fear that renovations are an excuse to reclaim the fresh market site and sell it for more lucrative uses. However, without renovations, including access to car parking and a cleaner appearance, such markets have trouble competing with adjacent supermarkets and minimarts. Half of the respondents to the survey of consumers at this fresh market (in the wealthier Central region) also shopped at the large modern supermarkets. This mixed mode of shopping contrasted with fresh markets in other regions where there was less patronage of modern retail outlets.

Sam Chuck fresh market in Suphanburi provides a contrasting history and appearance. For centuries Suphanburi has been a river market town, and has always sold a wide array of produce. In 2003, the 100-year-old wooden market was completely refurbished with a view to becoming a cultural institution and a tourist destination. During the week the major consumers at the market are local residents, while at weekends, tourists arrive in large numbers courtesy of bus tours. The value of the traditional character of the Sam Chuck market is being vigorously protected by stallholders who are threatened by the arrival of a new Tesco Lotus nearby. As in other localities(Reference Isaacs22) they have held public demonstrations against Tesco Lotus and the market site is festooned with a banner objecting to it. Emphasizing the threat to the community rather than the individual, a male vendor said:

I don't mind Lotus coming here: it's air conditioned, fair price and good quality, but I don't want it to come too close. If it's far and does not affect the community's economy, I'm okay, but otherwise it could be a threat.

Thai fresh market vendors, with support from their customers, are attempting to resist and compete with major supermarket retailers by drawing on claims of convenience, quality, value and tradition. At the same time, supermarkets are adopting some attributes of fresh markets in their attempts to gain market share(Reference Isaacs, Dixon and Banwell27).

Competing with supermarkets – what fresh markets do well

The material below encapsulates the key dynamics present across the seven fresh markets as market vendors attempt to compete with modern retailing in the following areas.

A Thai style of ‘convenience’

Fresh market vendors sold pre-cooked and packaged foods, including cooked vegetables, fried goods and bowls of curries, stir fries and local regional dishes. Curry pastes and powders are sold in single meal portions as well as in larger quantities, and some stalls also sold one meal sized plastic bags of fresh vegetables designed for soups. Fish are partially prepared by being de-headed and gutted. Small portions of sweets and desserts were also readily available. ‘Plastic bag housewives’(Reference Yasmeen28) frequently purchased the evening meal in a plastic bag on their way home from work. Vendors sold their produce in flexible amounts, ranging from a 10 kg sack of rice or large tins of oil to a single carrot, thus catering to individuals and families who may only have enough money to buy provisions for one or two meals at a time(Reference Schaffner, Bokal and Fink13) or who have little storage capacity. Many fresh market shoppers typically shopped daily in small quantities, thereby assuring that their food is fresh, easily transportable and affordable. Stallholders agreed that they charge more now per amount than in the past but sell in smaller quantities.

Food safety

Due to the common perception that fresh markets are less hygienic than supermarkets some markets have upgraded their infrastructure, while others are contemplating changes. Local officials monitor standards of hygiene, determining how food can be displayed and issuing instructions to vendors on cleanliness, food handling and storage. For example, at Chiang Mai's Tanin fresh market the public health department visited stallholders every couple of months. Stallholders are taught to wash and soak vegetables for 15 min with a tablespoon of baking powder dissolved in water to clean them and remove pests, before rinsing thoroughly. Surveyed retailers rated food safety, including anxiety about the use of pesticides and other chemicals, as the most important influence on consumers’ food choice. Over the preceding decade considerable improvements have been made to fresh markets to reduce food-borne disease risks(Reference Dixon, Banwell and Seubsman29), with one consumer observing that now ‘sellers are more sanitary in their methods’. Despite these improvements, supermarkets use food safety to claim superiority and create a point of distinction(Reference Goldman, Krider and Ramaswami30), particularly for aspiring middle-class Thais(Reference Isaacs22). They advertise use of the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points system; and their Western appearance, bright lights and polished floors reinforce perceptions that their produce is safe, modern and convenient. However, in the modern-looking, brightly lit and orderly Tanin fresh market, stalls were advertising produce that was certified as organic, a trend that is borrowed from the supermarkets. In other fresh markets many stalls displayed signs saying that they followed food safety standards and occasionally they displayed government certification (usually the Ministry of Agriculture's Good Agricultural Practices) which can inflate the price of a food considerably in both retail formats(Reference Vandergeest20).

Improved freshness and appearance

At the Chiang Mai Gate fresh market, one focus group stallholder said ‘if the vegetables don't look good, customers don't eat’. Thus, stallholders attempted to provide good-looking fresh produce. However, some vendors argued that the demand for produce that was blemish-free has led to the overuse of pesticides and the use of food colourings and additives. In this regard, many vendors and consumers thought that food may look better but not taste as good as in the past.

Protecting regional culinary culture

Fresh markets sell regional products. Sticky rice, which is regarded as ‘heartful’ (filling) in the north, is available in Chiang Mai markets; while in the south, hot and spicy curries are sold. Vendors and purchasers frequently expressed a preference for their regional foods while buyers often sought specific local vegetables(Reference Bunyannupap31). Stallholders also noted that markets were increasingly attracting Thai and international tourists who were looking for authentic Thai foods including regional products. Markets also play an important part in the ritual and symbolic routines of regional Thai life(Reference Bunyannupap31). When we visited the southern regional city of Nakhorn Sri Thamarat, the activities associated with an important festival at a nearby Buddhist shrine (the 10th month merit-making festival) were supported by the sale of festival foods in the market. Pramahathat, pagoda-shaped decorated food offerings, sat alongside various types of Kanom or pastries that stay fresh longer than other foods. These are offered to monks at the second of the three-month Buddhist period of restraint because the monks rely on foods that store well.

Fresh markets compete with supermarkets as local tourist attractions(Reference Isaacs22, 32) with the latter clearly recognizing the importance of the cultural dimension by selling regional produce and participating in local festivals. Thai families visit supermarkets on weekends often after payday. Children are given rides or treats while parents buy bulk quantities of mainly dry goods, laundry items, toiletries and clothes.

Implications of supermarket dominance for the Thai nutrition transition, health and well-being

Research elsewhere(Reference Reardon, Henson and Berdegue33) shows that ‘as supermarkets “take over” food retailing they become drivers of the overall food system’ (p. 415). This shift in power has implications for health and for local food environments.

Thais become increasingly exposed to obesogenic foods

Super/hypermarkets have proliferated in Thailand, increasing the availability, accessibility and affordability of energy-dense foods(Reference Hawkes34), because they sell processed foods more cheaply than traditional retailers although fresh foods were more expensive(Reference Vinkeles, Gomez and Colagiuri35). Supermarket shoppers are inclined to value foods such as Western-style bakery products(Reference Isaacs, Dixon and Banwell27) whereas fresh market-based respondents rarely ate Western foods.

A potential loss of accessible, plant-based, dietary diversity that is healthy and priced for poorer segments of the population

Fresh markets have traditionally sold locally harvested Thai plants in small quantities at affordable prices(Reference Dixon, Banwell and Seubsman29) with credit given to regular shoppers. Recently, an even greater profusion of imported, nationally and locally produced fruit and vegetables has become available in fresh markets(Reference Dixon, Banwell and Seubsman29). Local Thai vegetables and greens are displayed next to carrots from Australia and apples from China. A wider range of red and white meat now complements the traditional protein source of fish. Other traditional fresh produce and wild protein sources (lizards, insects, frogs) are now farmed and sold in fresh markets but are rarely sold in super/hypermarkets.

Loss of social capital connected to fresh markets

All sampled fresh markets illustrated the complex ways that fresh markets are integrated into daily rituals and in the process anchor a way of life for many consumers and for vendors. Reflecting on the attributes of the market in comparison to supermarkets, informants commented: ‘This is a way of life: always been like this’; ‘It's a great atmosphere’; ‘It brings great relations between producers and consumers’; ‘We bring a brother–sister relationship between buyers and sellers … it's still present, but not as much as the past’; and ‘People of my age, love the relationship with the sellers’. Consumers become interconnected with market vendors by making daily visits on their way home from work or other activities. As a result, they consolidated relationships with their preferred traders and established social networks based on familiarity and mutual benefit, which is similar to what Kirwan(Reference Kirwan36) described as ‘regard’.

A loss of livelihood particularly for women market retailers

Most fresh market stallholders, and roughly half the wholesalers, are women(Reference Jaibun37). They are often closely connected by intertwined kinship, friendship and commercial networks. Stalls were passed down through generations (often from mother to daughter), stallholders bought from and sold to each other, and consumers became part of these networks over many years. Market women's close relationships evolve into support roles which may include: financial sharing and support programmes, sickness benefit support, counselling services, assisting abused women and sharing market information(Reference Jaibun37). Thus women are particularly vulnerable to changes in retail food environments.

Undermining highly valued regional culinary cultures

Respondents proposed that fresh markets were the commercial repository of local and regional produce and dishes. In our surveys, safety, health and price were the first consideration in food preferences. ‘Culture’, meaning regional ingredients and dishes, rated second. Sellers and consumers conceded that recently there was some blurring of the boundaries with other regions and Western dishes being sold.

Discussion and conclusion

There are many features of fresh markets that super/hypermarkets cannot replicate. Thais shop and eat at fresh markets, often buying small amounts of mainly fresh foods daily at affordable prices and building health protection through the social capital that follows from strong social ties(Reference Kawachi, Kennedy and Lochner38). The markets supply tens of thousands of often independent livelihoods, particularly to women(Reference Jaibun37). In contrast, supermarkets do not establish a strong relationship between staff and consumers and they rely less on local produce. They are less adaptable as evidenced by the 2011 Thai floods when they ran out of stock quickly while fresh markets continued to operate. Nor are they as attractive for local or international tourists looking for an authentic culinary experience.

A limitation of the present study is that we have not yet directly investigated Thai health outcomes associated with supermarket growth. The current ready access to fresh markets appears to favour poorer Thais, who have lower BMI than wealthier and more urban Thais(Reference Banwell, Lim and Seubsman39, Reference Lim, Kjellstrom and Sleigh40), and the increase in hyper/supermarkets in Thailand is matched by the rapid growth of obesity(Reference Kelly, Sleigh and Banwell1). Longitudinal data from our 2005 cohort(Reference Sleigh, Seubsman and Bain41) along with ethnography of food retail environments and food consumption will be used to examine these relationships more closely.

It is uncertain whether fresh markets will continue to dominate the sale of fresh vegetables in Asia(Reference Goldman, Krider and Ramaswami30, Reference Reardon, Henson and Berdegue33, Reference Gorton, Sauer and Supatpongkul42) in the future. Globally, super/hypermarket chains have been successful at gaining market share over time with mixed public health and economic gains and losses. High-fat, sugary and salty foods become more accessible and affordable(Reference Hawkes17), and may usurp the place of raw staple foods in individual diets(Reference Vinkeles, Gomez and Colagiuri35). However, results depend on the existing food retail environmental and cultural context of supermarket growth(Reference Shannon9, Reference White43). In Guatemala frequent supermarket shopping is associated with increased purchases of processed foods associated with increased BMI(Reference Asfaw44), whereas diet quality improved slightly for the well-off in Tunis who used supermarkets(Reference Tessier, Traissac and Maire45). Supermarkets stock large volumes of processed foods and narrow the range of nearby competing food retailers which may sell cheaper, fresh food(Reference White43). A source of fresh, affordable food for poorer Thais may disappear along with fresh markets’ contributions to Thai culinary culture and to an esteemed and socially valued way of life (social capital) that contributes to positive social health status(Reference Kawachi, Kennedy and Lochner38). Poorer market vendors may suffer financial risk and eventually close as markets attempt to compete with supermarket claims of greater cleanliness, hygiene, food safety and the appeal of modernity itself. Eventually, if fresh markets disappear, Thai supermarkets may follow the Western pattern where they supply healthier diets to the educated and wealthy who can afford them, and cheaper, highly processed foods to the poor, thus increasing health inequalities.

National and particularly foreign-owned supermarket growth has been contentious in Thailand. Responding to their growth in more vulnerable regional centres, Mutebi(Reference Mutebi8) argues for greater policy intervention in addition to recent government regulations imposed on hyper/supermarkets limiting growth, location and trading hours. There should also be positive protection for fresh markets with financial assistance for infrastructural upgrades, cheap credit to stallholders(Reference Figuié and Moustier25), and more government promotion of fresh markets as safe, healthy food retail outlets.

Ultimately, the decrease in fresh markets would put food security (dietary needs and food preferences)(46) at risk, particularly for poorer Thais. Other Asian countries, which are also anticipating rapid increases in obesity and weight-related diseases, will be monitoring Thai policy responses and health outcomes closely.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: This study was supported by the International Collaborative Research Grants Scheme with joint grants from the Wellcome Trust UK (GR071587MA) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; 268055), and a global health grant from the NHMRC (585426). Conflicts of interest: There is no conflict of interest for any author. Authors’ contribution: All authors were involved in fieldwork. C.B. and J.D. took the lead in writing the paper and other authors contributed to revisions. Acknowledgements: The authors thank Ivan Hannigan for the map; the staff at Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University (STOU) who assisted with student contact and the STOU students who are participating in the 2005 cohort study; and Dr Bandit Thinkamrop and his team from Khon Kaen University for guiding them through the complex data process. Ethics clearance for the Thai health-transition study was obtained from STOU.