While non-communicable diseases (NCD) are a developing global epidemic, the problem is already well advanced in many Pacific Island countries(Reference Coyne1), and they are a growing health, social and economic issue in the region. In Fiji, around 60 % of deaths are due to heart disease, heart failure, stroke and hypertension(2). In Tonga, a recent survey(3) found that 91 % of adults were overweight and 67 % were obese. These problems are also present in the younger population, with a survey of 11- to 16-year-olds finding that 36 % of boys and 54 % of girls were overweight or obese(Reference Smith, Phongsavan and Havea4).

Poor diets are a contributing factor in the increasing NCD problem, reflecting changes in the food systems within the region. Extensive changes in areas such as agriculture, fisheries and trade have altered food supply chains and overall food accessibility and availability(Reference Hughes and Lawrence5, Reference Schoeffel6). Across the region, this has been associated with a move away from the traditional diets and a growing reliance on the imported foods(Reference Hughes7) such as rice, meat products and sugary snacks. Food energy and fat/oil availability have increased considerably in recent decades(Reference Hughes7), and the increasing food imports parallel increasing energy density of the diet(Reference Ulijaszek8).

Efforts are ongoing to improve both diet and lifestyles throughout the region, with many countries developing NCD strategic plans of action. In the area of diet, the focus of these strategies is mainly on education to encourage individuals to change their behaviour. There is little action using broader-based policy interventions(Reference Hughes and Lawrence5, Reference Hughes7) to promote changes in food supply chains and food systems, despite the recommendations at a regional meeting of the Ministers of Health to ‘develop, implement, enforce and evaluate policies’ such as legal and fiscal measures(9) and widespread support of the WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health(10). There is little understanding within the region of the wider policy environment influencing food supply chains.

Policy interventions can have a considerable impact on changing food systems and in turn on the eating habits of the population(11–Reference Adeyi, Smith and Robles13), but have not been widely used(Reference Swinburn14, Reference Lang and Rayner15), particularly in the Pacific(Reference Hughes and Lawrence5, Reference Hughes7). With limited local capacity and resources, countries like Fiji and Tonga require a process that is practical and solution-oriented to identify which new policy approaches have the potential to provide the most benefits to diets. This necessitates an understanding of the local food system in terms of existing policies, potential areas of change and the overall environment that would affect the reality of policy change. The purpose of this research was to implement a systematic evidence-informed process, combined with the stakeholder’s opinion, to enable these countries to identify the most feasible and targeted policy interventions, which would have the most impact on NCDs.

In the present paper, we report the results of this research, and their relevance to the policy and practice. We discuss the lessons learned and implications within the region and elsewhere.

Methods

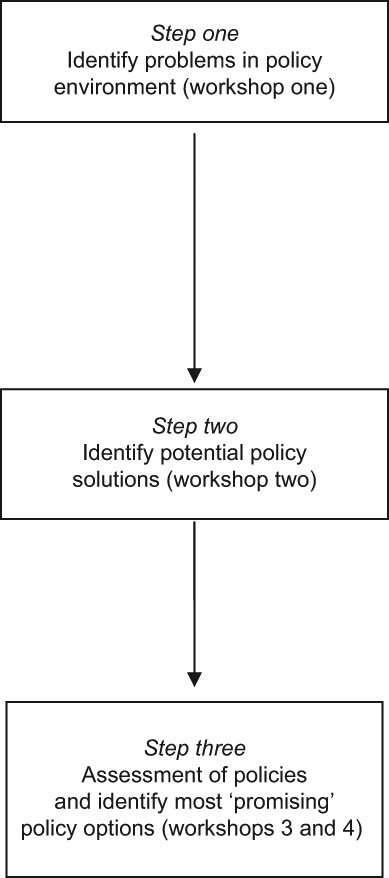

A participatory approach was developed based on an informed multisectoral stakeholder group. Policy advisors from organisations such as the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture, Commerce and the private sector and civil society were recruited in both Fiji and Tonga in 2007. Ethics approval was obtained from the national ethics committees and from Deakin University, and informed consent was obtained from all stakeholder group members. Structured around a series of short 1–2 d workshops in each country, stakeholders were led through a series of processes to identify the problem policy areas, potential policy solutions and then to prioritise those solutions (see Fig. 1). The participatory methods used were slightly different in the two countries, but achieved the same outcomes. In-depth research between workshops was used to accumulate detailed information on identified policies, food supply, diets and NCD problems. Information was sourced from the local departments, stakeholders, internet sources and the local media. This was disseminated to stakeholders during the workshops and via email between sessions to support evidence-informed decision-making.

Fig. 1 Outline of research process

In Step one, the policy problems were identified. Policy problems are defined in this research as existing weak policies, existing policies that are detrimental to health (barriers) and areas where no policy exists (gaps). A modified problem-tree approach(Reference Snowdon, Schultz and Swinburn16) was used in Fiji to develop an understanding of the current policy environment affecting food system and diets. An alternative approach in Tonga used the food supply chain and government and non-government sectors to identify policy problem areas. A simple scoring and logic theory was then used to assess the possible impact of the identified policy problems and policy gaps on NCD. In Step two, potential solutions were developed to each problem(Reference Snowdon, Schultz and Swinburn16), and the logic theory was again used to assess the potential impacts of these solutions on NCD.

In Step three, the policy change options were assessed to identify those that represented the preferred interventions for each country. This considered how likely the policy change was to occur, the potential impacts on NCD and on the community in general(Reference Snowdon, Potter and Swinburn17). The likelihood of policy change was assessed using a multicriteria decision-making approach, and considered political and cultural (community) acceptability, technical and cost feasibility and legal feasibility with regard to existing trade agreements. A simple weighting scheme(Reference Wilson, Rees and Fordham18, Reference Baltussen and Niessen19) was used to allow greater emphasis to be placed on more influential factors. Wider community implications such as unintended negative effects elsewhere were assessed using a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) screening tool (outlined in more detail previously(Reference Snowdon, Potter and Swinburn17)). Potential impacts on NCD were assessed through a participatory process(Reference Snowdon, Potter and Swinburn17) and also through cost-effectiveness modelling. Due to time limitations, only a shortlist of policy options underwent modelling (the shortlist was developed by stakeholders based on a preliminary prioritisation process).

On the basis of the results of these evidence-informed assessments, the stakeholders then categorised the policy options into one of the three categories:

1. Recommended for action: expected to be effective, cost-effective, feasible and acceptable.

2. Not recommended as priority actions: show some promise, but action needs further consideration as it has some problems, e.g. acceptability, cost, technical capacity and side-effects. Further consideration could be used to assess how likely the potential problems were. In the short term, however, implementing the policies in the ‘recommended for action’ category would be the priority.

3. Not recommended action: these policies had serious problems, and should not be implemented.

Evaluation forms were completed by the stakeholders at the end of the final workshop to provide feedback on the process. The process was completed in Fiji late in 2008 and in Tonga in March 2009.

Results

Process evaluation showed a high stakeholder support for this research across all sectors. Missing members were followed up post-workshop in one-to-one meetings to gain their input into the research process; this helped to maintain the involvement of the key sectors throughout.

Policy problems

In both countries, stakeholders’ expertise and local knowledge enabled the groups to develop extensive lists of policy problems which could contribute to poor diets. In Fiji, e.g. around eighty policies were identified ranging from import taxes to poor land use policies, and around sixty were identified in Tonga. These were grouped into six core areas, as illustrated in Table 1, which includes representative examples. In both countries, the initial identification included a number of policies or gaps that, after further assessment, were considered to be unlikely to contribute significantly to the NCD problem. This was more apparent in Tonga, where around a third of the policies were assessed as unlikely to affect NCD, e.g. ‘no requirement for rice fortification’ in Fiji and ‘regulation of bread size’ in Tonga. This assessment of relevance to NCD was guided by the problem trees in Fiji and the development of the logic models in Tonga.

Table 1 Core areas of policy problems identified, with representative examples from Fiji and Tonga

VAT, value-added tax.

Potential policy solutions

The initial solution development produced considerable numbers of potential changes to existing policies and new policies, related to the extensive policy problems identified in Step one. In Fiji, around 100 policies were identified, and more than eighty policies were identified in Tonga. The majority was targeted at specific problems identified in Step one, but some were ‘floating’ solutions; they were associated with a dietary problem area, but not with a specific problem policy. For example, ‘regulating drink vending machines in all public buildings’ in Fiji and ‘food policy for the government-funded workshops’ in Tonga. Representative examples of the solutions generated are shown in Table 2 using the same core areas as in Table 1.

Table 2 Core areas of potential new policy solutions identified, with representative examples from Fiji and Tonga

Those indicated with an * are modifications to existing policies.

After initial generation of a policy option idea, the definition was tightened. This often resulted in a number of slightly different versions being developed. For example, regarding fish imports, versions included reduction in import duty for tinned fish from either 20% to 10% or from 20% to 0%, or a reduction in import duty for all types of fish.

Assessment of policies

This part of the research, where each policy option was assessed for feasibility and impact, was the most time-consuming process for the stakeholders and the research team. Despite the range of sectors involved, consensus was rapidly reached most of the time. Only a few of the assessments were more contentious, but these were resolved through extended discussion between stakeholders.

In both countries, the feasibility weightings selected by the stakeholders were similar for the categories: cultural, political, technical, cost and legal-related issues. The greatest dominance over the feasibility was given to political acceptability, and the least to cultural acceptability. The feasibility of the total-weighted scores ranged from a low feasibility of two out of four (‘banning sale of high-fat potato chips’) to high feasibility of four out of four (‘school food policy’).

The HIA screening tool was completed for each policy option; this revealed extensive potential side-effects for many of the policies, both positive and negative. For example, while ‘reducing import duty on vegetables’ could enhance sales and turnover for stores selling imports, it could reduce sales of vegetables grown by local farmers.

Assessment by stakeholders of potential impacts identified that some policies were less likely to be successful in achieving dietary change, or were likely to have only a small effect. For example, increasing the import duty on mutton flaps (a fatty meat offcut) from 15 % to 20 % was considered unlikely to affect diets, as the price change would be so small.

An initial shortlist of twenty-five to thirty policy options of most interest was selected at this point to undergo cost-effectiveness modelling. The costs to government for implementing each policy change were assessed, and the potential reductions in NCD mortality were modelled based on the likely effectiveness on diets.

Identification of the ‘most promising’ policy options

On the basis of the results of all the assessments, including the modelling, the stakeholders identified a shortlist of specific preferred policy options for implementation. The shortlist consisted of twenty-three and forty-one policies in Fiji and Tonga, respectively (many of which were complementary measures). They included tax-related changes, price control changes, advertising controls, school food policies and enhanced support for the local food production and marketing. In all, 43 % of the recommendations were related to altering prices of foods and drinks, 19 % to increasing access and availability of local fresh foods and 16 % to controlling the marketing of less healthy foods and drinks and enhanced health promotion. A summary is shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Shortlist of policy options selected by Fiji and Tonga

VAT, value-added tax.

*Specified by nutrient profiling system(Reference Rayner, Scarborough and Boxer22, 23).

Those indicated with † are modifications to existing policies.

Discussion

This research represents the first systematic, evidence-informed assessment of policy changes to control diet-related NCD in Fiji and Tonga. The participatory approach enabled evidence and informed stakeholder opinion to be used in the process. The method has identified policies that are likely to be effective, targeted and are feasible locally. This will ensure that efforts to implement these changes are more likely to result in success. The research included agreement on the necessary actions to ensure that policy change occurs, which will build on existing national strategies and committees on NCD and nutrition, and will utilise the stakeholder group further. The clear basis and justification for each policy change will also be important in advocacy for action. In addition, clear documented reasons for non-selection (e.g. low technical feasibility or poor likely effectiveness) will be utilised to ensure that inappropriate policy changes are not pursued.

The range of policy changes recommended in each country covers many issues. There was considerable emphasis in both countries on altering the relative prices of healthier and less healthy options, with recommendations to implement policies together to further increase the price differential between the healthier and less healthy options. This reflects the concern that the healthier options are currently often more costly than the less healthy ones, and that the demand is strongly affected by the price. The second area of emphasis was on increasing availability and access to local fruits and vegetables and fish, in part to reduce reliance on imports, and therefore to increase the food security. Policies to control the marketing and promotion of less healthy foods and drinks and enhance health promotion were also focused upon.

This participatory research process and its findings have considerable advantages for Fiji and Tonga. The analysis of the existing policy environment has enabled the identification of a more defined, targeted and relevant set of policy objectives for implementation. In addition, the research process could be easily repeated at future dates to update the findings in view of likely ongoing policy and political changes. Its linkage with the NCD strategic plans will increase the likelihood of policy implementation, and will ensure the documentation of areas of responsibility to ensure action. A number of the policy change recommendations were complementary to existing activities or to other policy recommendations, and this should also enhance implementation and effectiveness. The research process had the additional benefit of developing local capacity, and enhancing the knowledge of policy advisers from across the sectors of the impact of their sector on diets and NCD. This will facilitate the implementation of policy changes and also enhance cross-sectoral collaboration in the future. Ultimately, the benefits of this research cannot be fully realised until the policy change occurs. Long-term evaluation of this project has been planned and will enable an assessment of the factors involved in policy uptake or non-uptake.

The research process and its implementation have their limitations, particularly in terms of its reliance on only one stakeholder group in each country. It is possible that repeating the process with different members could generate different findings. The process, however, included a comprehensive range of senior individuals and was able to develop consensus, and it is likely that the results would be broadly applicable. Nevertheless, further consultation on some policy options might be beneficial to support adoption, and this is planned. An additional limitation is that only some of the policy options were modelled for cost-effectiveness, and this could have led to the exclusion of non-modelled policies from the shortlist. Ideally, all of the policy options would have been modelled, but this would have been difficult because of time limitations and also insufficient data availability in these two countries. The overall process used is also based on an assumption that policy development can be informed by evidence and a systematic process. Therefore, a limitation of this research design is that the evidence-informed approach to gaining consensus at meetings (and policy formulation) competes with the socio-political and economic forces(Reference Marmot20, Reference Davies and Nutley21).

The results of each step of the research in Fiji and Tonga have similarities, but it is clear that the research needs to be implemented at national level, as there were significant intercountry differences. However, there is scope for collaboration and knowledge transfer within the region, based on other countries’ assessments. The research process could be easily transferred to neighbouring Pacific Island countries, and is also likely to be applicable in other small developing countries.

Conclusion

This research has shown that the participatory approach method is well suited to the food policy research in the Pacific Islands. It has highlighted the importance of developing an understanding of the food system locally, before attempting to modify that system in the pursuit of improved health. The results have also emphasised the impact of non-health policies on diets, and the importance of considering health when policies are developed across sectors. This research has highlighted the potential for evidence-informed public health decision-making.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: This research was funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and by Deakin University. The support of the Governments of Fiji and Tonga is gratefully acknowledged. The involvement and commitment of the stakeholder group members is deeply appreciated. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Contributions of authors: W.S. is the primary author of the present paper. She developed the methods and led the research. M.L. and B.S. contributed to the method development. J.S. and P.V. supported the implementation of the research.