Mortality rates from CVD have halved in Western Europe in the last 20 years(Reference Rayner and Petersen1). Many factors that predispose to the development of CVD have been thoroughly investigated(Reference Yusuf, Hawken and Ounpuu2). Some of these cardiovascular risk factors (CRF) cannot be modified (advanced age, male gender, heredity), while some can be modified (smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, physical inactivity, overweight and obesity). Additional modifiable CRF include specific dietary patterns such as wine, fruit and vegetable consumption as well as physiological factors such as stress.

Europe has been experiencing a marked increase in obesity rates, which have doubled over just a few years(Reference Finucane, Stevens and Cowan3). This continuing trend in obesity is a critical public health threat because of its potential transition into higher prevalences of diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia(Reference Mokdad, Ford and Bowman4). Furthermore, recent national survey data show that hypertension prevalence is much higher in European countries than in North America(Reference Wolf-Maier, Cooper and Banegas5).

Few published data are available to characterize current CRF prevalence and to monitor trends in CRF in the Italian population(6–Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9). The aims of the present study were therefore to assess the prevalence of major CRF in a large community-wide sample of the Italian population and to examine potential differences in the distribution of CRF across Italian macro-areas.

Methods

Study population

The present cross-sectional survey included 24 213 unselected adults (12 626 men and 11 587 women) aged 18 years and older (mean age 56·9 (sd 15·3) years; median (25th, 75th percentile) 59 (46, 68) years), who volunteered to participate in a community-wide screening programme to promote healthy lifestyle (‘Misuriamoci’), organized by the Italian Red Cross and supported by the Italian Ministry of Health. Participants were recruited in 193 Italian towns over a 2 d period in March 2007 in response to an extensive media campaign. Advertising was conducted by radio and television announcements, newspapers, magazines, billboards and bus posters.

Measurements

Standardized methods were used to collect and measure risk factors.

Weight and height were measured without shoes and heavy clothing; a standard electronic scale and a wall height ruler were used respectively for weight and height. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in metres). The classification of overweight and obesity was based on the following categories(10): overweight as BMI = 25·0–29·9 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2.

Waist circumference was measured with an anelastic tape with the participant in standing position, at the level of the umbilicus. According to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria(Reference Grundy, Cleeman and Daniels11), abdominal obesity was defined as waist circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women.

Blood pressure was recorded as the average of two measurements after participants had been sitting for 5 min, applying an appropriately sized cuff on the right arm. The average of the two consecutive readings was used in the analysis. Hypertensive participants were defined as those with systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/≥90 mmHg or on regular antihypertensive treatment(12).

Fasting cholesterol, TAG and glucose levels were determined from finger-prick capillary blood samples using a Multicare® diagnostic device (http://www.multicare.it). High blood total cholesterol was defined as ≥200 mg/dl(13). Hypertriacylglycerolaemia was considered as serum TAG ≥150 mg/dl(Reference Grundy, Cleeman and Daniels11). Lipid-lowering therapy was defined if participants reported taking lipid-lowering drugs. Dyslipidaemia was considered as participants reporting high blood total cholesterol and/or high serum TAG and/or taking lipid-lowering medication(Reference Grundy, Cleeman and Daniels11, 13). Impaired fasting glucose (hyperglycaemia) was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level in the range 100·0–125·9 mg/dl and diabetes was considered as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl or if participants reported taking antidiabetic drugs(14).

For wine, fruit and vegetable consumption, a commonly used serving size was specified and participants were asked ‘if and how often they had consumed that unit’. Current wine consumption was recorded as glasses/week (one glass is defined as 4 fl oz of wine or a drink equivalent). An average daily intake of 1 or 2 drinks for men and 0·5 to 1 drink for women was considered as recommended(Reference Lichtenstein, Appel and Brands15). Daily and/or weekly consumption was asked for fruit and vegetables. An average of 8–10 servings/d for fruit and vegetables was considered as recommended(16).

Current smokers were defined as participants who smoked one or more cigarettes daily.

As regards geographic distribution, data were analysed as a whole and by the following macro-areas (i.e. areas comprising more regions, generally contiguous): North-west (Valle d'Aosta, Piemonte, Liguria and Lombardia); North-east (Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto and Emilia Romagna); Centre (Toscana, Marche, Umbria and Lazio); South (Campania, Abruzzo, Molise, Calabria, Puglia and Basilicata); and Islands (Sicily and Sardinia).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means and standard deviations or as frequencies in presenting continuous or categorical variables, and are adjusted by age, averaging the 5-year age groups and stratifying the data for men and women. All the data have been weighted using the Italy population pyramid for 2005 (US Census Bureau, international database); in particular, we stratified by age and sex and then we performed a weighted average.

A survey regression analysis was used for averaged age and gender adjustment for each town unit and then we adjusted for age and gender at the individual level. Separate prevalence results are presented for men and women in single macro-areas and linear and logistic regression models were performed to obtain comparisons and to take into account the role of potential confounders (age and sex).

A post hoc power calculation indicates that the available sample allows analysis of variance comparison tests to detect a difference of 5 % between groups, with power >94 % and α < 0·05.

Analyses were performed using the statistical software package STATA 9·2 SE (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). A P value < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

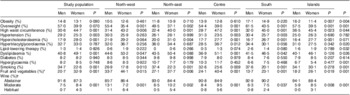

The main demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the study population according to gender and macro-area are shown in Table 1. Overall, average BMI was 26·9 (sd 4·5) kg/m2 and men had a higher mean BMI than women (27·6 (sd 4·1) v. 26·3 (sd 4·8) kg/m2). Men and women on average exceeded the sex-specific waist circumference cut-off (mean: 101 (sd 11) cm in men; 91 (sd 13) cm in women). The average systolic blood pressure value was 134 (sd 19) mmHg and men showed a higher mean value than women (136 (sd 18) v. 132 (sd 19) mmHg). Average TAG level was high (155 (sd 81) mg/dl) and women showed a higher mean level than men (158 (sd 84) v. 152 (sd 78) mg/dl).

Table 1 Main demographic, clinical and metabolic characteristics of the study participants stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007

WC, waist circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; FPG, fasting plasma glucose.

Mean values were significantly different from those of men (survey regression model adjusted for each town unit): *P < 0·05.

†Significantly different among Italian macro-areas adjusted for gender; linear and logistic regression models.

‡Significantly different among Italian macro-areas adjusted for age and gender; linear and logistic regression models.

Figure 1(a) illustrates the number of surveyed towns and macro-areas, and Fig. 1(b) presents data on the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes in each geographical macro-area. Overall, 22·7 % of the population was identified as obese; the highest prevalence of obesity was observed in the South, while the lowest was observed in the North-east macro-area. The overall prevalence of hypertension was 59·6 % and both North-west and North-east macro-areas showed the highest prevalence, while the Islands showed the lowest. The overall prevalence of dyslipidaemia was 59·1 % in the study population; a higher prevalence was observed in the North-west and North-east compared with the South and Islands macro-areas. The overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 15·3 %; the South and Islands macro-areas showed a higher prevalence than the North-west, Centre and North-east macro-areas.

Fig. 1 Maps showing (a) the number of surveyed towns and macro-areas (![]() $$$$, Islands;

$$$$, Islands; ![]() $$$$, South;

$$$$, South; ![]() $$$$, Centre;

$$$$, Centre; ![]() $$$$, North-west;

$$$$, North-west; ![]() $$$$, North-east) and (b) geographical differences in the prevalence (

$$$$, North-east) and (b) geographical differences in the prevalence (![]() $$$$, very high;

$$$$, very high; ![]() $$$$, high;

$$$$, high; ![]() $$$$, low) of cardiovascular risk factors according to macro-area; Italy, 2007

$$$$, low) of cardiovascular risk factors according to macro-area; Italy, 2007

Table 2 shows the prevalence of some CRF in the study population stratified by gender and macro-area. Overall, 56·7 % of the study population had abdominal obesity (waist circumference above the gender-specific cut-off value); the South population showed the highest prevalence (60·4 %), while the North-east population showed the lowest (52·3 %), and men were affected more than women in the study population (57·0 % v. 56·4 %) and in Northern and Islands macro-areas. Smoking habit concerned 19·8 % of the study population and the Islands population showed the highest prevalence (25·9 %), while the North-west population showed the lowest prevalence (15·6 %). Men smoked more than women in both the study population (25·2 % v. 14·0 %) and each macro-area.

Table 2 Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the study participants stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007

†Survey regression analysis adjusted for each town unit for average age and gender.

‡Linear and logistic regression models adjusted for age and gender.

The prevalence of consuming fruit and vegetables 8–10 servings/d was 40·0 % in the general population. The prevalence of people with fruit and vegetable intake in the recommended range was: North-west, 55 %; North-east, 50 %; Centre, 45 %; Islands, 30 % and South, 25 %. Women adhered more than men to the nutritional recommendations, both in the study population and in each macro-area (Table 3).

Table 3 Prevalence of fruit and vegetable consumption within the recommended range and wine consumption higher than the recommended intake in the study participants stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007

†Survey regression analysis adjusted for each town unit for average age and gender.

‡Linear and logistic regression models adjusted for age and gender.

§Fruit and vegetable consumption within the recommended range of 8–10 servings/d.

∥Wine consumption higher than the recommended intake: moderate, 1–2 drinks/d for men and 0·5–1 drink/d for women; habitual, >2 drinks/d for men and >1 drink/d for women.

Concerning wine consumption, it was higher than the recommended intake in 6 % of the study population (North-west, 8 %; North-east, 7 %; Centre, 7%; South, 4 %; Islands, 3 %). Women showed a higher prevalence than men both in the study population and in each macro-area (Table 3).

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of participants showing none, one or more CRF in the study population stratified by gender. As risk factors we analysed: (i) obesity, overweight and high waist circumference; (ii) hypertension; (iii) dyslipidaemia; (iv) diabetes and hyperglycaemia; (v) smoking; (vi) fruit and vegetable consumption lower than the recommended intake; and (vii) wine consumption higher than the recommended intake. The prevalence of having between two and five CRF was 84 %.

Fig. 2 Prevalence of (from zero to seven) cardiovascular risk factors (CRF; obesity/overweight/high waist circumference, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes/hyperglycaemia, smoking, fruit and vegetable consumption lower than the recommended intake, wine consumption higher than the recommended intake) in the overall population (![]() $$$$) and by gender (

$$$$) and by gender (![]() $$$$, men;

$$$$, men; ![]() $$$$, women); Italy, 2007

$$$$, women); Italy, 2007

Table 4 describes the prevalence of having zero to seven CRF (obesity/overweight/high waist circumference; hypertension; dyslipidaemia; diabetes/hyperglycaemia; smoking; fruit and vegetable consumption lower than the recommended intake; wine consumption higher than the recommended intake) among Italian macro-areas and the effect of macro-area on the distribution of CRF in the study population.

Table 4 Prevalence (%) of (from zero to seven) of cardiovascular risk factors (CRF; obesity/overweight/high waist circumference, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes/hyperglycaemia, smoking, fruit and vegetable consumption lower than the recommended intake, wine consumption higher than the recommended intake) in the study participants stratified by macro-area; Italy, 2007

Effect of macro-area on the distribution of CRF in the Italian study population: P < 0·001 among macro-areas, adjusted for age and gender.

Consistent with previous studies(Reference Miccoli, Bianchi and Odoguardi17, Reference Hu, Qiao and Tuomilehto18), when stratifying our data into three age groups, i.e. 18–39, 40–65 and >65 years, we observed an increased prevalence of some CFR with age. Particularly, the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, wine consumption and fruit and vegetable consumption increased with age, while smoking decreased with age and dyslipidaemia reached a peak in the 40–65-year age group (see Appendices 1 to 3).

Discussion

The present study provides novel evidence about the current prevalence and distribution of major CRF in a large community-wide sample of the Italian adult population, including 24 213 participants. Altogether the findings are worrisome and clearly indicate that obesity and hypertension represent a relevant public health problem in Italy. However, results should be interpreted with caution because of self-selection bias; this may be a possible source of discrepancy with other national results.

There was a consistent north-to-south increasing gradient in the prevalence of obesity, diabetes and smoking, while a consistent south-to-north increasing gradient was found in the prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia (Table 2, Fig. 1). Wine and fruit and vegetable consumption was significantly higher in the northern macro-areas than in the south (Table 3).

Comparing our results with data from the National Institute for Statistics (ISTAT) survey in 2007(7) reveals that the prevalence of obesity has increased considerably over the last few years (overall 22·7 % v. 9·8 %), while the prevalence of overweight has increased by a smaller degree (overall 44·7 % v. 34·2 %). This discrepancy in obesity prevalence may be due to self-reported data collected by ISTAT, compared with direct measurements used in our study. In fact, obese individuals tend to overestimate their height and to underestimate their weight, leading to an underestimation of obesity prevalence in studies based on self-report measurements(Reference Visscher, Viet and Kroesbergen19). Moreover, comparing our data with previous studies(8, Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9, Reference Berghöfer, Pischon and Reinhold20) using direct measurements, almost the same prevalence of obesity and overweight was found. According to previous reports the prevalence of obesity was quite similar between men and women, while the prevalence of overweight was nearly double in men compared with women(7, Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9). Recent changes in lifestyle in Western and developing countries, such as physical inactivity and unhealthy eating habits, are likely to account for the increasing prevalence of obesity. Nowadays, women have more stringent weight standards and engage in more efforts to avoid being overweight(Reference Hedley, Ogden and Johnson21).

Consistent with the ISTAT data(7), the Southern population showed the highest prevalence of obesity in the present study while the lowest prevalence of overweight was found in the North-east population. We believe that excessive total energy intake and a low degree of physical activity may account for the high prevalence of obesity in the Southern population(Reference Miccoli, Bianchi and Odoguardi17, Reference Barbagallo, Cavera and Sapienza22, Reference Giampaoli and Vanuzzo23).

By comparing our results with data from the Italian Epidemiologic Cardiovascular Observatory (OEC) as part of the Progetto CUORE(8), we found an increase in the mean waist circumference value both in men (101 v. 95 cm) and women (91 v. 85 cm). This agrees with a positive trend of the waist circumference gradient observed over the last few years(Reference Ike, Chandra and Boev24). The prevalence of abdominal obesity was higher in the South than in other macro-areas and in men than women in the general population; however, according to previous studies the prevalence of abdominal obesity was higher in women than men in the Centre macro-area(Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9, Reference Miccoli, Bianchi and Odoguardi17).

A striking finding of the present study is the high prevalence of hypertension (59·6 %) in our population, which is much higher than in previous reports of both ISTAT (12·9 %; 13·6 %)(6, 7) and OEC (48·5 %)(8). However, ISTAT surveys analysed a wide age range (0 to >80 years) and used self-reported data which may underestimate the prevalence of hypertension, failing to detect hypertensive people who are not aware of their condition. Moreover, according to more recent guidelines(12), we used cut-off points for hypertension lower than those used in previous studies(6–8). Interestingly, when analysing our data using the cut-off of ≥160/95 mmHg similar to OEC(8), we found comparable prevalence figures for hypertension prevalences in both genders (men: 34 % v. 33 %; women: 28 % v. 28 %). Based on current guidelines(12), the prevalence of hypertension has raised in our population.

We found differences in the prevalence of dyslipidaemia between genders, with a higher prevalence of men on pharmacological treatment than women (Table 2). In particular, high TAG levels are commonly observed in individuals with abdominal obesity(Reference Bard, Charles and Juhan-Vague25). In parallel to the rise in prevalence of overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity, the prevalence of hypertriacylglycerolaemia was almost doubled in our study compared with a previous study(8). This could be the result of unhealthy eating habits in the Italian population and increased intakes of fast foods and other foods with high fat content, over the last years. On the contrary, in our study the prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia was lower than in a previous survey(8), but almost comparable to that in a more recent study(Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9).

Also the prevalence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia was almost double compared with previous surveys(7, 8), but the prevalence of diabetes was similar to that in a more recent study(Reference Donfrancesco, Lo Noce and Brignoli9). The growing prevalence of diabetes in our study population and especially in the Southern population is likely due to the increased prevalence of obesity(Reference Giampaoli and Vanuzzo23, Reference Wild, Roglic and Green26). In addition, consistent with previous studies(8, Reference Miccoli, Bianchi and Odoguardi17, Reference Verhave, Hillege and Burgerhof27), men showed a higher prevalence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia than women, while women showed a higher prevalence of dyslipidaemia than men(Reference Sofi, Innocenti and Dini28).

Over the last 50 years, many studies have evaluated the associations between food groups and chronic diseases or weight gain, with an increasing recognition of the role of nutritional factors in the aetiology of these diseases(Reference Joshipura, Hu and Manson29, Reference Buijsse, Feskens and Schulze30). A low incidence of CVD in the Mediterranean countries, mainly due to the typical nutritional model, has been demonstrated(Reference Keys, Menotti and Karvonen31). Unfortunately, in Italy there has been a gradual abandonment of this nutritional model during the past few decades(Reference Trichopoulos and Lagiou32, Reference Centritto, Iacoviello and di Giuseppe33). Actually, nutritional recommendations for fruit and vegetable consumption have been raised from 5 servings/d to 7 (or 9) servings/d(16) in order to prevent the major chronic diseases. In our study population, many participants (60 %) were far from reaching the optimal intake for these foods(16). Even by considering the recommended range as between 3 and 5 servings/d(34–37), only 69 % of the study population reached the optimal intake for fruit and vegetables(Reference Sofi, Innocenti and Dini28). Unexpectedly, in South and Island macro-areas, the cradle of the Mediterranean diet concept, we found the lowest prevalence of people reporting fruit and vegetable consumption in the recommended range. Although we did not have data concerning the participants’ socio-economic status, we believe that these findings could be related to low household income in the South and Islands macro-areas(Reference Giskes, Turrell and Patterson38).

No recent surveys have examined wine consumption according to the recommended amount(Reference Lichtenstein, Appel and Brands15). In the last few years there has been a steady decline in wine consumption, whereas the consumption of other alcoholic beverage types (e.g. beer) has increased(39). Interestingly, a very low prevalence of habitual wine consumption (6 %) was found in the general population. However, although moderate wine consumption is considered part of healthy lifestyle, the prevalence of current wine abstainers was very high (76 %) in our population. Moreover, consistent with ISTAT data(6), we found a south-to-north increasing gradient in the prevalence of people showing high wine consumption.

Trends of smoking prevalence are declining as supported by our data (19·8 %) and findings from previous studies such as OEC (25·5 %) and ISTAT (23·9 %; 21·7 %)(6–8). In particular, the proportion of people who have quit smoking has increased over the last few years(7), after the banning of smoking in public places with the introduction of the Italian anti-smoking legislation in January 2005(Reference Cesaroni, Forastiere and Agabiti40). However, consistent with previous studies(6–8), men smoked more than women in the present survey; the South and Islands macro-areas showed the highest prevalence of smokers(8).

As hypertension, obesity/overweight/high waist circumference, dyslipidaemia and diabetes/hyperglycaemia occurred frequently in the study population, it is not surprising that we found 84 % of people having between two and five CRF and 90 % of people showing more than one CRF (Fig. 2). These findings are deeply alarming. Even if the co-prevalences of CRF were quite similar among the Italian macro-areas, the South and Islands seemed to be the highest-risk macro-areas because of showing the highest prevalence of participants having between two and five CRF (Table 4).

Study strengths and limitations

The major strength of our study is the wide community sample across several Italian macro-areas. Furthermore, anthropometric measurements were made by direct examination according to standard protocols. In addition, we analysed several classical and new CRF.

However, there are some limitations to our study, which should be considered for the interpretation of the present results.

First, surveys based on volunteers may be affected by selection bias. Volunteers with unhealthy lifestyle habits may be more motivated to perform the screening programme, resulting in the screening detecting a high prevalence of CRF in this population. However, selection bias may also operate in the opposite direction, whereby the more educated and health-conscious (and likely healthier) individuals of the population may volunteer for screening, resulting in the screening detecting a low prevalence of CRF in this population(Reference Froom, Melamed and Kristal-Boneh41). Moreover, because participants were recruited in 193 Italian towns in response to an extensive media campaign, the rural population may be not adequately represented.

Second, a further limitation of the study is the absence of data on previous personal history of CVD and of data concerning socio-economic status, physical activity levels, insulin resistance, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and minor CRF.

Third, fruit and vegetable consumption, wine intake and cigarette smoking are based on self-reported data and thus the observed prevalence may have been affected by recall bias. In particular, it is known that the intake of health promoting foods such as fruits and vegetables is over-reported by individuals and their consumption is known to remain seasonal in many countries in spite of the spread of the global economy. Self-reported wine consumption is likely to underestimate the real level of consumption. Estimates for cigarette smoking were not validated by biochemical tests.

Conclusions

The present study provided novel evidence on current prevalences and geographic variations for major CRF in Italy. Data are worrisome and suggest a high prevalence of obesity/overweight and hypertension in the Italian population.

Although the decreased cardiovascular mortality in Italy(Reference Palmieri, Bennett and Giampaoli42) has been attributed to improved medical therapies and changes in major CRF, CVD prevalence remains high. Therefore, there is a pressing need for targeted prevention programmes aimed at modifying the lifestyle and eating habits of the Italian population to reduce the risk of CVD. Our results will provide the evidence base to inform effective prevention programmes, which must also take into account the differences in the prevalence of CRF among Italian macro-areas.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by ‘la Federazione nazionale dei titolari di farmacia italiani’ (FEDERFARMA), Takeda Italia Farmaceutici, Multicare, FederFARMACO, Pacini editore and the Italian Ministry of Health. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contributions were as follows: study design, B.G., R.L., B.M.; statistical analysis, A.P.; collecting data, C.F.; data processing, R.L., B.G., S.S.; writing, R.L., B.G., L.B., S.S. The authors thank Dr Giuliano da Villa and Brunella Maruotto for their assistance in the collection of the data presented in this paper.

Appendix 1 Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the study participants aged 18–39 years stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007

Appendix 2 Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the study participants aged 40–65 years stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007

Appendix 3 Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the study participants aged 65 years and over stratified by gender and macro-area; Italy, 2007