In countries such as Australia, the USA and the UK, the majority of school-aged children exceed dietary guideline recommendations regarding the consumption of discretionary foods, that is, those foods higher in salt, sugar and saturated fat(1–3). Unhealthy dietary habits in children increase the risk of a variety of immediate and long-term health conditions, including dental caries, diabetes, obesity and CVD(Reference Armfield, Spencer and Brennan4–Reference Must, Spadano and Coakley7). As such, improving child nutrition has been identified as a global health priority(8).

Children consume approximately one-third of their daily energy intake during school hours(Reference Bell and Swinburn9). Food consumed at school typically comes from either the school’s food service, such as the school canteen or cafeteria, or via a packed lunch(Reference Bell and Swinburn9). In Australia, like the UK(Reference Evans, Greenwood and Thomas10), the majority (>85 %) of food consumed at school is brought from home via a school lunchbox, typically packed by parents(Reference Bell and Swinburn9). In Australia, school lunchboxes have been found to contain an average of 3·5 serves of discretionary choices(Reference Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer11), far exceeding Australian dietary recommendations for primary school-aged children(12), and over 2800 kJ(Reference Sutherland, Nathan and Brown13), equivalent to 40 % of a primary school-aged child’s entire daily energy intake(14). As such, strategies that are successful in achieving even modest improvements in the nutritional quality of foods packed in school lunchboxes could make an important contribution to improving child nutrition(Reference Cochrane, Davey and de Castella15).

The use of text-based messaging via mobile phone applications has the potential to reach large numbers of parents and students at low cost and represents a promising intervention to improve the packing of healthy school lunchboxes(Reference Payne and Lister16). Text message-based interventions have been found to be highly acceptable by end-users(Reference Payne and Lister16), and systematic reviews have demonstrated that text-based messaging can be an effective tool for disease prevention and management across a variety of health behaviours and conditions(Reference Cole-Lewis and Kershaw17). Furthermore, a recent randomised trial utilising text messaging as part of a broader multicomponent intervention found that it was effective in reducing discretionary choices and increasing ‘everyday’ healthy choices in school lunchboxes(Reference Sutherland, Nathan and Brown18).

Whilst there is evidence to suggest that text-based messaging may be effective in improving the nutritional quality of foods packed in a lunchbox, systematic reviews suggest that personalisation, tailoring of message content and message framing may enhance their effects(Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19). Furthermore, the use of behaviour change frameworks in message development can help to identify factors that may improve intervention effects, and their use is recommended in the development of content for text message-based interventions(Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19). The Health Belief Model (HBM) is one behaviour change theory that suggests that health risk behaviour is mediated by individual beliefs and perceptions(Reference Rosenstock20,Reference Becker21) . The HBM has been used as a theoretical model in the development of mobile health or m-health interventions(Reference Cho, Lee and Islam22), and a number of its constructs have been found in meta-analyses to be effective in predicting a range of health behaviours(Reference Carpenter23). The HBM was designed to explain, and so help determine, which beliefs should be targeted in communication campaigns to modify health behaviours. As such, it may be a particularly relevant theory to apply in efforts to further enhance the impact of the text-message based strategies to improve lunchbox packing behaviours given the importance of communication for text-message based interventions.

Text-message based interventions have considerable potential reach(Reference Hall, Cole-Lewis and Bernhardt24) and may represent a lower cost means of delivering information at a population relative to in-person approaches. If delivered at a population level, even small improvements in their effect, achieved through deliberate and data-driven (optimisation)(Reference Wolfenden, Bolsewicz and Grady25) approaches, may yield meaningful impacts at the population level. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess:

-

1. The impact of different m-health message content targeting the same HBM construct on parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox.

-

2. The impact of m-health messages targeting different HBM constructs on parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox.

-

3. Whether the personalisation and credibility of the m-health message source increases parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox.

Method

Study design and setting

This study employed an experimental design. All participants were read one randomly selected message for each of the six domains of the HBM (six messages in total) and additionally one message which was (or was not) personalised and one message which varied based on the suggested source of the information provided (independent variable). After each message, participants were then asked about their intention to pack a healthy lunchbox (dependent variable). The study was conducted via a computerised-assisted telephone interview (CATI) of parents of primary school-aged children, from twelve Catholic primary schools in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales, Australia. The Hunter region encompasses major city and regional areas and is characterised by a high proportion of the population from low socio-economic backgrounds(26).

Sample

The sampling frame for this study was parents with a child enrolled in Kindergarten to Grade 6 who had previously participated in an m-health randomised controlled trial of a physical activity and healthy lunchbox intervention(Reference Sutherland, Nathan and Brown18) and had consented to be contacted and invited to participate in future child health research studies.

Data collection and measures

Participants, who had consented to being contacted again in the m-health randomised controlled trial (Reference Sutherland, Nathan and Brown18), were telephoned to complete a survey via CATI between October 2018 and December 2018. Telephone interviews were delivered by experienced telephone interviewers.

Participant characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of parents and children assessed as part of telephone interviews conducted during the preceding m-health randomised controlled trial were used in this study, including parent postcode of residence, highest level of education, employment status and sex.

Message development

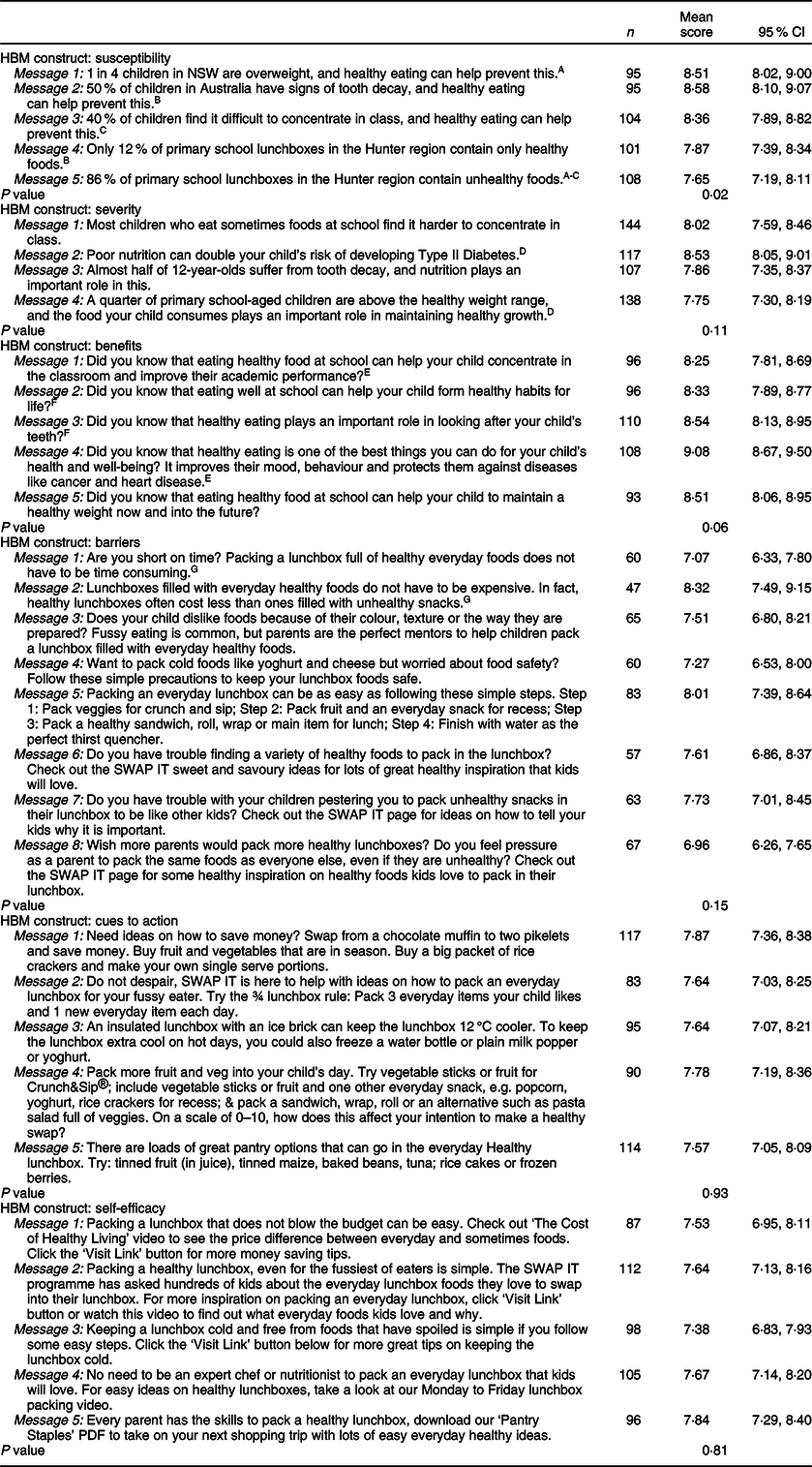

M-health messages were developed by a team of public health nutritionists, behavioural scientists and school education researchers. Content of messages was developed to align with HBM constructs (susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy)(Reference Rosenstock20,Reference Becker21) . Within each HBM construct, a variety of messages were developed addressing topics relating to nutrition of children and lunchboxes, as described in Table 2:

-

1. Perceived susceptibility: defined as the belief that a person will develop a disease or condition(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Five messages were developed targeting each of five common adverse effects of poor dietary intake reported in the literature to represent a concern for parents including child overweight and obesity(5), Type II diabetes(Reference Chiuve, Sampson and Willett6,Reference Must, Spadano and Coakley7) , tooth decay(Reference Armfield, Spencer and Brennan4), dietary impacts on school performance and behaviour at school(Reference Carey, Singh and Brown28). All text messages used published estimates in Australian samples to communicate susceptibility of children to each of the adverse effects of poor child diet, such as the percent of children with overweight or obesity, tooth decay prevalence and risk of Type II diabetes.

-

2. Perceived severity: defined as the belief of the seriousness of a condition or the consequences associated with leaving a condition untreated(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Four messages were developed targeting four of the most severe adverse effects of poor dietary intake reported in the literature including the effects of overweight and obesity(5,Reference Carey, Singh and Brown28) , Type II diabetes(Reference Chiuve, Sampson and Willett6,Reference Must, Spadano and Coakley7) and tooth decay(Reference Armfield, Spencer and Brennan4). All text messages developed reported published statistics for the Australian context(Reference Armfield, Spencer and Brennan4,Reference Sutherland, Nathan and Brown13,Reference Hardy, King and Kelly29) in an effort to communicate the seriousness and severity of conditions associated with poor dietary intake.

-

3. Perceived benefits: defined as the belief of potential positive aspects by partaking in a health action(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Five messages were developed that highlighted five benefits of improved dietary intake for children, commonly reported in the literature and by formative evaluation with Australian parents including benefits of healthy eating at school and improved performance at school(Reference Carey, Singh and Brown28), formation of healthy habits throughout all life stages(12), child tooth development(Reference Armfield, Spencer and Brennan4), impacts on mood and behaviour(Reference Carey, Singh and Brown28) and maintenance of a healthy weight(12). Each topic was chosen to complement topics covered in messages aligned to the perceived susceptibility and severity constructs.

-

4. Perceived barriers: defined as the belief of the costs (both tangible and psychological) of partaking in a health action(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Eight messages were created targeting the most common parental barriers in packing a healthy lunchbox based on formative evaluation with Australian parents in the current literature. Each message reflected one parental barrier including time constraints(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32), cost(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32), fussy eating(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32), food safety(Reference Bathgate and Begley30,Reference Hawthorne, Neilson and Macaskill31) , knowledge(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32), peer and parental influence(Reference Hawthorne, Neilson and Macaskill31).

-

5. Cues to action: defined as factors or strategies that trigger action or readiness to change(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Of the five messages developed, each message described simple strategies parents could use to improve the nutrition of school lunchboxes aligned to perceived parental barriers. The cues to action complemented the parental barriers of cost, food safety, knowledge and convenience(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32).

-

6. Self-efficacy: defined as the belief or confidence in a person’s ability to take action(Reference Glanz, Marcus Lewis and Rimer27). Five messages were developed that included ‘how-to’ information relating to parental barriers of packing a healthy lunchbox, in particular, cost, food safety, knowledge and skills, to complement cues to action messages(Reference Bathgate and Begley30–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman32).

Additional messages were also developed to test the effects of different sources of information and personalisation of messages. Messages were developed varying the source of information as being from either an academic institution (the University of Newcastle) a local health service (Hunter New England Health, Health Promotion team), dietitians, or their local school, based on literature suggesting that educational systems, health services and health professionals are a trusted and credible source of information(Reference Dutta-Bergman33) as seen in Table 4. In addition, personalised messages were developed using the child’s name and school grade level v. messages that did not use the child’s name or grade level. Personalisation of messages using the participants or child’s name or other socio-demographic features has been reported in the literature as being considered more meaningful and may lead to higher engagement with content(Reference De Leon, Fuentes and Cohen34). Examples of messages are highlighted in Table 4.

Instrument development and experimental manipulation

Each parent was randomly assigned one lunchbox message per HBM construct and one message each in relation to the credibility of the source and child’s age and name personalisation. After interviewers read each message, participants were asked about their intention to pack a healthy lunchbox on a ten-point scale (0; no intention to pack a healthy lunchbox to 10; every intention to pack a healthy lunchbox). Intention was used as an indicator for packing a healthy lunchbox as it demonstrates a parent’s reflective motivation to perform a behaviour or action, in this case, the packing a healthy lunchbox for their child(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West35). Survey questions were developed by a team of public health nutritionists, behavioural scientists and school education researchers based on similar items commonly used to assess behavioural intention(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West35,Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston36) . Questions were pilot tested for comprehension and understanding and reviewed by experienced telephone interviewers.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9·3) statistical software. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. Residential postcodes of parents were used to classify participants as residing in lower or higher socio-economic areas using the median score for the state of New South Wales according to the 2016 Socio-Economic Index for Areas(37). Parents postcodes were also used to characterise the geographic locality of participants, as either rural or urban using the 2016 Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia(37). For each HBM construct, a linear mixed regression model was used to determine if there were was a significant variation in behavioural intention scores between messages targeting that construct. Where significant effects (P < 0·05) were reported, using those same models, post hoc pair wise comparisons were undertaken to identify between which specific messages behavioural intention scores significantly differed. To assess differences in behavioural intention scores between each construct, a mean behavioural intention score for all messages in each construct was calculated, and linear mixed regression model was also used to compare these across constructs. Where significant effects (P < 0·05) were reported, post hoc pair wise comparisons were undertaken to identify between which constructs mean behavioural intention scores significantly differed. All models included a random effect for school to account for potential clustering. Statistical tests were two-tailed with an alpha of 0·05.

Results

Sample

From the original study, 790 (98 %) parents agreed to be contacted for future studies. There were no significant differences on any socio-economic characteristics between parents who did and did not agree to be contacted. In total, 511 parents completed the CATI. Of the consenting and participating parents, 91 % were female, 82 % were from major cities, 85 % were employed and 88 % had an educational level of a certificate or diploma or higher. The characteristics of the consenting parents are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Sample characteristics

Impact of messages targeting the same Health Belief Model constructs on parents intention to pack a healthy lunchbox

Linear mixed regression analyses identified significant differences in behavioural intention scores between variant messages targeting the behavioural constructs of ‘susceptibility’, ‘severity’, ‘benefits’ and ‘barriers’ but not ‘cues to action’ or ‘self-efficacy’ (Table 2). Post hoc pair wise comparisons of the effects of individual messages within each construct revealed the following significant differences. For the HBM construct of ‘susceptibility’, messages reporting susceptibility statistics regarding tooth decay, overweight and obesity and poor classroom concentration linked to unhealthy food intake had higher behavioural intention scores than messages reporting statistics regarding discretionary foods (P < 0·05) typically packed in children’s lunchboxes. Behavioural intentions scores among parents receiving messages reporting susceptibility statistics on tooth decay were also significantly higher than those receiving messages regarding healthy foods typically packed in student lunchboxes (P = 0·04). For the HBM construct of ‘severity’, messages linking nutrition to diabetes risk had significantly higher behavioural intention scores than messages targeting overweight (P = 0·02). In relation to ‘benefits’ messages about protection against chronic disease scored higher messages regarding the benefits of good nutrition on academic performance (P = 0·008). For the HBM construct of ‘barriers’, the message reporting healthy lunchboxes often cost less than ones filled with unhealthy snacks had behavioural intention scores higher than messages suggesting that packing a lunchbox full of healthy everyday foods does not have to be time consuming (P = 0·03). Results relating to parent’s intention to pack a healthy lunchbox based on the same HBM construct are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2 M-health messages targeting the same Health Belief Model (HBM) constructs on parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox

A-GSimilar subscripts delineate messages were significantly different to each other, at P < 0·05. Participants were asked about their intention to pack a healthy lunchbox on a ten-point scale (0; no intention to pack a healthy lunchbox to 10; every intention to pack a healthy lunchbox).

Impact of messages targeting different Health Belief Model constructs on parents intention to pack a healthy lunchbox

Linear mixed regression analyses identified significant differences in mean behavioural intention scores across HBM constructs (P < 0·001). The findings of post hoc pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 3. The highest mean behavioural intention score was for ‘benefits’ (8·57 (8·34; 8·80)), whilst the lowest mean score was ‘barriers’ (7·55 (7·32; 7·79)). ‘Severity’ and ‘susceptibility’ both scored significantly higher than ‘barriers’ (0·48, P < 0·001 and 0·63, P < 0·001), ‘cues to action’ (0·32, P = 0·007 and 0·47, P < 0·001) and ‘self-efficacy’ (0·41, P < 0·001 and 0·56, P < 0·001). There were no significant differences between ‘barriers’, ‘cues to action’ and ‘self-efficacy’, or ‘cues to action’ and ‘self-efficacy’ on behavioural intention scores.

Table 3 Post hoc pairwise analyses comparing mean behavioural intention scores (to pack a healthy lunchbox) for Health Belief Model (HBM) constructs

* Significant difference to each other, at P = 0·001.

† Significant difference to each other, at P < 0·001.

‡ Significant difference to each other, at P = 0·007.

Impact of personalisation and credibility of source of messages on parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox

There were no significant differences in behavioural intention scores of parents receiving messages from a dietitian, a university, a health promotion team or the school (P = 0·37). Behavioural intention scores did not differ on items in which messages were personalised based on the child’s name or grade level (Table 4).

Table 4 M-health messages targeting personalisation and credibility of source on parent’s intention to pack a healthy lunchbox

Discussion

The study found that the use of different HBM constructs in developing message content influenced parent’s intention to pack a healthy lunchbox. Message content focussed on the benefits of packing healthy lunchboxes appeared to have particularly strong effects on behavioural intentions relative to messages related to other HBM constructs. Differences were also found in behavioural intention scores between messages assessing the same HBM construct. Personalisation of messages based on child name or school grade or altering the stated source of information provided in the message did not significantly influence parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox. The findings suggest that theoretically guided approaches in the development of text message-based intervention are likely to be effective in optimising the impact of such interventions in improving the foods consumed by children at school.

The study found that HBM constructs of ‘benefits’, ‘susceptibility’ and ‘severity’ were more influential than ‘cues to action’, ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘barriers’. Lower behavioural intention scores on ‘cues to action’, ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘barriers’ suggest that such messages may have less salience. The findings may reflect parent’s belief that they are already packing a healthy lunchbox for their children or that they already have the skills and capacity to do so(Reference Adamo and Brett38). If this is the case, incorporating a form of individualised feedback demonstrating the opportunity for improvement in packing of healthy lunchboxes, such as self-assessment tools, may improve the potential impact of messages targeting these constructs. Alternatively, the findings may reflect the limited ability of text messages aligned to these constructs (relative to others) to enhance behavioural intentions for the packing of healthy lunchboxes, suggesting that other strategies may be required.

Messages relating to benefits of healthy lunchboxes scoring higher than all other HBM constructs have been reported in other health promotion studies in parents. A study conducted in 2018 reported that messages relating to the reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages in children that were positive or ‘gain-framed’ had higher motivation scores in parenting practices than those that were negative or ‘loss-framed’(Reference Zahid and Reicks39). Similarly, a meta-analysis conducted in 2014 which included 94 studies reported that gain-framed messages were significantly more likely to encourage health prevention behaviours than loss-framed messaging(Reference Gallagher and Updegraff40). The use of the HBM construct of benefits in framing messages may therefore highlight an impactful way to improve parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox.

Surprisingly, the personalisation of messages with children’s names and grade levels had no effect on parents’ intention to pack a healthy lunchbox, which has commonly been found in other studies(Reference Cole-Lewis and Kershaw17,Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19) . A systematic review on the efficacy of text-based message interventions in health promotion conducted in 2013 reported that messages that were targeted and tailored were significantly associated with intervention efficacy with a greater effect size(Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19). The review reported that tailoring of messages occurred in studies in a variety of ways including demographic and psychosocial tailoring(Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19). The resulting no effect of personalisation of messages based on children’s names or grade levels in our study may, therefore, be due to the level of tailoring and personalisation being too crude in only the name or grade level of the child changing in each message. More sophisticated approaches in the tailoring of lunchbox messages may provide better effects on behavioural intentions in the future. However, ethically obtaining and using personalised child information for the purpose of delivering health interventions may represent a considerable challenge for the application of such text-message based interventions. Similarly, the study found no effect on different information sources on intention to pack a healthy lunchbox. This may have been due to all sources of information included in the study considered to be credible(Reference Dutta-Bergman33).

The strengths of this study include the use of an experimental design in which parents were randomly allocated a series of messages. The use of an experimental design strengthens the internal validity of the findings. Messages were also developed by an expert team of public health nutritionists, behavioural scientists and school education researchers using the current evidence base in relation to school lunchboxes and health behaviour risks. Nonetheless, the study had several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. Participants in the study were predominantly university educated from major cities. Additionally, the sampling frame was composed of parents who had previously participated in a physical activity and lunchbox intervention and may be more health oriented and motivated to improve health behaviour than the community at large. Such participant characteristics reduce the generalisability of the study findings. In addition, data on the ethnicity of parents were not collected which make it difficult to ascertain the representativeness of the sample. The use of a CATI in which parents were read out lunchbox messages instead of parents being able to visually see and read messages may have impacted on the validity of results. Differences exist in the attention, understanding and response to information presented in visual v. verbal formats(Reference Kiat and Belli41,Reference Knoll, Otani and Skeel42) . As such, the effects of verbally delivered messages on behavioural intentions reported in this study may not generalise to delivery of the same message via text. Furthermore, in practice, the delivery of text-message based interventions also provides the opportunity to link users with other resources and information sources. This may be particularly important for HBM constructs such as barriers and cues to action where practical resources may be particularly helpful. Testing the effects of messages in a more naturalistic context, and in a form for which they may most optimally influence behaviour, may provide the most useful evidence to assess their effects. In future, recruiting parents from general community samples and testing the effects of messages with embedded links to further resources or information as appropriate may be a more applicable means of assessing their potential.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the study limitations, the study provides useful insights that can assist in the development of text-based messages in an effort to improve the nutritional quality of school lunchboxes. Optimising the potential impact of messages in this way represents an efficient means of maximising the potential effects of such interventions prior to the conduct of large-scale randomised trials. Nonetheless, future randomised trials are required to confirm the effect of changes in message content on lunchbox packing behaviour of parents and dietary intake of children. Furthermore, a range of opportunities are available to enhance the impact of text message-based interventions beyond message content. For example, the timing and frequency of messages may influence its effects, as may embedding other multimedia content or other strategies to enhance user experience and engagement(Reference Head, Noar and Iannarino19,Reference Grady, Yoong and Sutherland43) . The use of adaptive trial designs may be particularly useful in improving the efficiency and maximising the impact of text message-based interventions(Reference Pallmann, Bedding and Choodari-Oskooei44).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Not applicable. Financial support: The work was supported by Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI), Hunter Children’s Research Foundation (HCRF) and Hunter New England Population Health. R.S. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) TRIP Fellowship (grant number APP1150661); N.N. is supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (grant number APP1132450) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; LW is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (grant number APP1128348), a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (grant number 101175) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship. Funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: A.B., R.S., N.N. and L.W. conceived and designed the study. A.B., R.S., L.W., L.J., N.H., A.C., R.R., A.W. and K.R. designed the intervention. K.R. managed data collection. A.B. assisted with data cleaning. C.L. led statistical analysis. A.B. drafted the manuscript, with all other co-authors contributing to drafts of the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 06/07/26/4.04), the University of Newcastle (reference number H-2008-0343) and the Maitland Newcastle Catholic Schools Office. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.