A school feeding programme (SFP) is a targeted social safety net intervention that may provide both educational and health benefits to socio-economically disadvantaged schoolchildren(1). The benefits include alleviation of short-term hunger, increasing school enrolment, reducing school dropout and absenteeism(1,Reference Jomma, McDonnell and Probart2) . SFP may encourage girls’ education and narrow sex disparity in school enrolments(Reference Poppe, Frolich and Haile3). Linking home-grown SFP to local agricultural production may boost local economies and increase market opportunities for subsistence farmers(Reference Gelli, Neeser and Drake4).

Globally, nearly 400 million children are fed daily at school. Even in many high-income countries with low prevalence of undernutrition, school feeding remains an important component of national social protection systems(5). However, according to the World Food Program, in the developing world, 66 million schoolchildren attend classes hungry. In Africa alone, the figure is as high as 23 million(6). The coverage of SFP is lowest (18 %) in low-income countries where the need is highest(7).

In Ethiopia, malnutrition among schoolchildren remains a major concern(Reference Hall, Kassa and Demissie8–Reference Wolde, Birihan and Chala10). According to a national survey conducted in 2008, 22·3 % and 23·1 % of primary schoolchildren were stunted and thin, respectively(Reference Hall, Kassa and Demissie8). In Ethiopia, a World Food Program-sponsored SFP was piloted in 1994 in the Tigray region(Reference Poppe, Frolich and Haile3). The national coverage of the programme gradually increased, and in 2016, more than a million children in drought-affected areas were reached(11). Very recently, the SFP expanded to major urban areas including Addis Ababa. The National Nutrition Program(12) and the National School Health and Nutrition Strategy of Ethiopia(13) have identified promotion of home-grown SFP as a key nutrition-sensitive intervention to combat malnutrition.

Despite the assumption that SFP improve the education outcomes of children, empirical evidence is scarce. A recent review documented the positive effects of SFP on school enrolment; however, the impacts on school absenteeism and academic achievement remain equivocal(Reference Jomma, McDonnell and Probart2). In Ethiopia, the few available studies on significance of SFP for school participation reported conflicting findings(Reference Zenebe, Gebremedhin and Henry14–Reference Yohannes16). Further, the studies employed cross-sectional designs and hence are liable to systematic errors. Therefore, the objective of this study was to measure the effect of school feeding on improved class attendance and academic performance of second-cycle primary school (grade 4–8) students in selected food insecure districts of Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study compared class absenteeism and academic performance of students enrolled in SFP beneficiary and non-beneficiary second-cycle primary schools in four rural districts of Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. The study was conducted in the 2017/2018 academic year. Baseline information was gathered at enrolment, and class attendance and academic performance were measured at the end of the first and second semesters of the year.

Study setting

The study was conducted in sixteen schools from four SFP-targeted rural districts (Borecha, Dara, Bona and Loko Abaya) of Sidama zone. Sidama is located approximately 300 km south of the national capital Addis Ababa. The zone covers nearly 10 000 km2 area and is administratively divided into ten districts. In 2017, the zone had approximately four million inhabitants of whom 95 % were rural dwellers(17). Sidama is characterised by three agroecological zones: lowlands (20 %), midlands (48 %) and highlands (32 %). The economy in the area is reliant on rain-fed subsistence agriculture(Reference Regassa and Stoecker18). According to a recent study, 18 % of the households in the area were food insecure and the prevalence of severe food insecurity was as high as 48 %(Reference Regassa and Stoecker18).

In the Ethiopian education system, primary education is divided into first (grade 1–4) and second (grade 5–8) cycles. At the time of the survey, 111 s-cycle public schools (second-cycle primary schools) were functional in the four study districts, of which 27 were targeted by the SFP. Inclusion of schools into the programme is determined based on extent of food insecurity in the school catchment area as judged by administrative bodies and donors. Students enrolled in SFP-targeted schools daily receive a free cooked school meal prepared from cereals, legumes and vegetables. The nature of the SFP implemented in all the schools was more or less the same in terms of food served and frequency of feeding.

Study subjects

Students enrolled in sixteen rural second-cycle primary schools (eight schools with SFP and eight schools without SFP) in the aforementioned four districts were eligible for the study. Students registered in SFP-targeted schools were considered as SFP beneficiaries, whereas those enrolled in non-targeted schools were assumed otherwise.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 programme(Reference Faul, Erdfelder and Lang19), assuming that the two primary outcomes (class absenteeism and academic performance) would be compared between the two groups using one-tailed mean difference test. The sample size was computed with 95 % confidence level, 80 % power, one-to-one allocation ratio between the two groups, medium effect size (d = 0·4) and design effect of 2. Further, 20 % compensation for possible dropout was added. Ultimately, the sample size of 480 (240 SFP beneficiaries and 240 non-beneficiaries) was determined.

Sampling technique

From each of the four districts, two SFP-targeted and two non-targeted schools, in total sixteen schools, were included in the study. In each district, two schools with SFP were selected at random among the SFP-targeted schools and matching schools without SFP were identified using predefined matching criteria – being within the same district and having comparable agroecological features. In each school, thirty students were selected from the available sections using a proportional stratified sampling technique. Ultimately, based on class rosters and a table of random numbers, simple random sampling (SRS) was performed to select the students. With the intention of maximising the sample size of the study, at enrolment study, subjects who were not willing to take part in the study were replaced by randomly chosen eligible children from the same section (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the study

Variables of the study

The exposure of interest was SFP status (beneficiary v. non-beneficiary), while the two primary outcomes were total number of school-days missed in the year and average academic score of the students in the academic year. School dropout rate (yes/no) was also considered as a secondary outcome. Factors considered as potential confounders included: age and sex of the child, maternal and paternal educational status, household wealth index, monthly income and food insecurity, head of the household (male v. female) and enrolment of the household in the Productive Safety Net Program.

Baseline data collection

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the study participants and their caregivers were assessed at enrolment using interviewer-administered questionnaires prepared in the local Sidamu Afoo language. The data were primarily collected from the parents of the index children through home interviews by trained and experienced enumerators and supervisors. Household food insecurity was assessed using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale and categorised as food secure or mild, moderate or severe food insecurity(Reference Deitchler, Ballard and Swindale20).

Outcome ascertainment

Class absenteeism rate and academic performance were measured based on school administrative records. Class attendance was measured as the total number of days children were absent from school in the year, while class performance was quantified based on the average score of the students (minimum 0 and maximum 100) for all ten courses they attended in that year. The ten courses were English language, Amharic language, Sidamu Afo language, Mathematics, Social Science, Sport Education, Civics, Integrated Basic Sciences (grades 5–6), Art (grades 5–6), Music (grades 5–6), Physics (grades 7–8), Chemistry (grades 7–8) and Biology (grades 7–8). Each course was rated with a scale ranging 0–100.

Statistical analysis

We used STATA version 14 for data analysis. Principal Component Analysis was performed for computing household wealth index – a composite index of living standard – based on multiple variables including materials used for house construction, access to improved drinking water source and sanitation facilities, and ownership of livestock, private house and agricultural land. Principal Component Analysis was done using varimax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was acceptable (0·64), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant. Only variables that had communality scores above 50 % were retained in the analysis. Ultimately, the factor with the highest eigenvalue was taken and divided into three equal tertiles: poor, middle and rich.

Pearson’s χ 2 or Fisher’s Exact tests were used to check the presence of systematic differences between students retained in the study (n 463) and lost to follow-up (n 17) depending on whether the assumptions of χ 2 test were fulfilled or not. χ 2 test was also performed for comparing SFP beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries based on socio-economic characteristics. Factors that were significantly different (P value < 0·05) between the two groups were statistically adjusted using multivariable regression models.

Mixed effects negative binomial regression for count outcome was fitted to measure the effect of the SFP on school absenteeism. Poisson regression for count outcome was not used because the assumption of equidispersion, as evaluated by comparing the mean and variance, was violated. Mixed effects linear regression was performed to assess the effect of the SFP on average academic performance, and the assumptions of the model (normality and homoscedasticity of error terms and linearity of relationship) were assessed using partial plots and found to be satisfied. School dropout was modelled using mixed effects Poisson regression for binary outcome. In all multivariable models, absence of multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factor and found to be within the acceptable range (variance inflation factor < 10). In all the mixed effects models, random intercept was set for schools. In these mixed effects models, we did not consider school-level variables as predictors because all schools had more or less similar profile – all were public schools, second-cycle primary schools and the teacher to student ratio was very comparable.

Results

Baseline characteristics

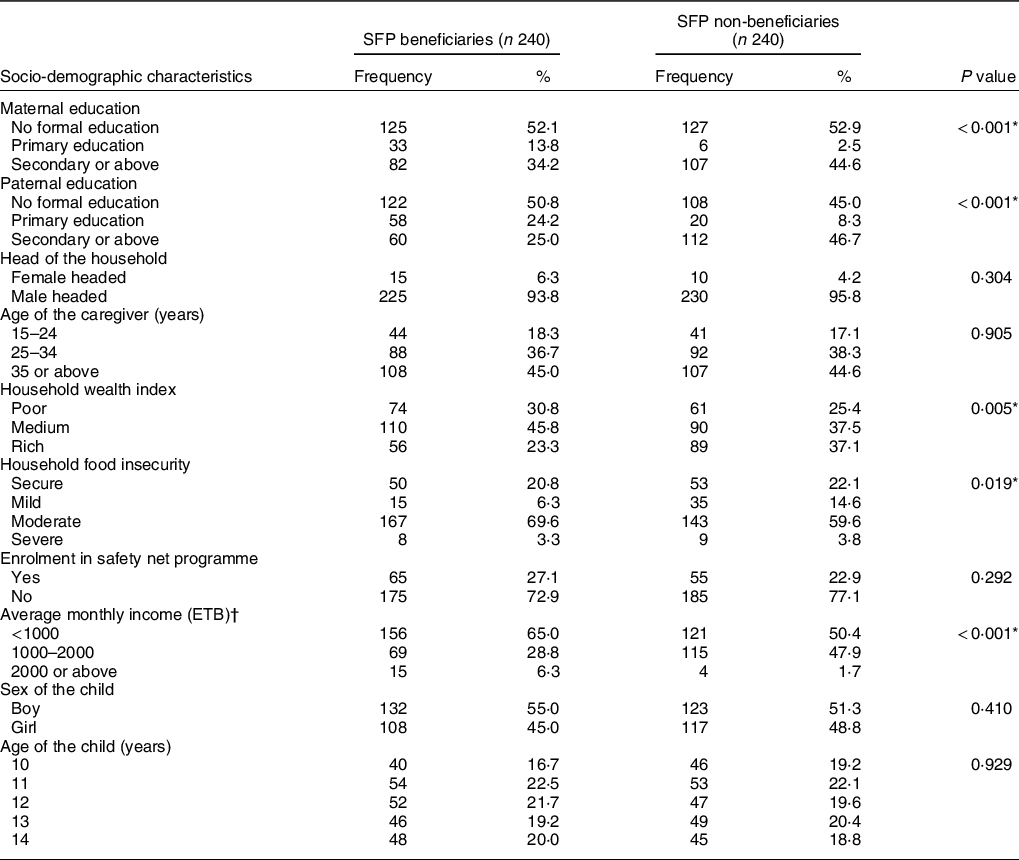

Table 1 summarises the baseline socio-demographic characteristics of the 240 SFP beneficiaries and 240 non-beneficiary children and their caregivers. Comparison between the two groups showed that maternal and paternal educational statuses were significantly better among non-beneficiary children than their counterparts (P < 0·001). SFP beneficiaries were economically disadvantaged as measured by both wealth index and monthly income (P < 0·005). Similarly, 72·9 % of SFP beneficiary children were from households with moderate or severe food insecurity in contrast to 63·4 % among non-beneficiary children (P = 0·019). The two groups were balanced in the other features including age and sex of the child, sex of the household head, maternal age and enrolment in Productive Safety Net Program (Table 1).

Table 1 Basic characteristics of school feeding programme (SFP) beneficiary and non-beneficiary children and their caregivers, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

* Significant difference at P value of 0·05 (χ 2 test);

† ETB, Ethiopian birr, at the time of the study, 1 USD was roughly equivalent to 30 ETB.

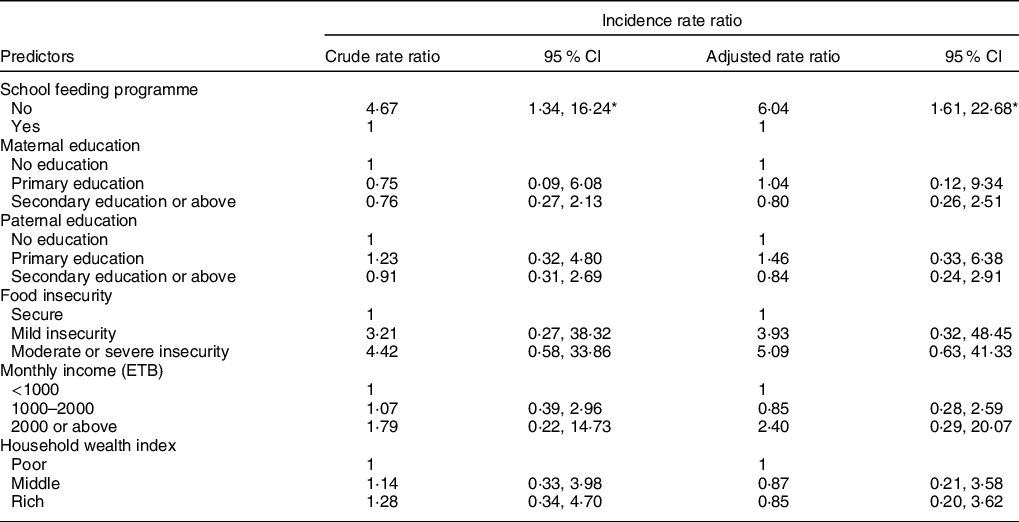

School dropout

Among 480 students enrolled in the study, 17 (3·5 %) dropped out of school over the academic year. Dropout rate was significantly lower (1·3 %) among children participating in SFP compared with non-participants (5·8 %) (P = 0·007) (Table 3). In the multivariable Poisson model adjusted for five unbalanced variables, the risk of dropout was six times higher (adjusted rate ratio = 6·04; 95 % CI 1·61, 22·68) among non-beneficiary children (P = 0·008) than their counterparts (Table 2).

Table 2 Relationship between enrolment in school feeding programme and school dropout among schoolchildren in Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

ETB, Ethiopian birr.

* Significant association at P value of 0·05.

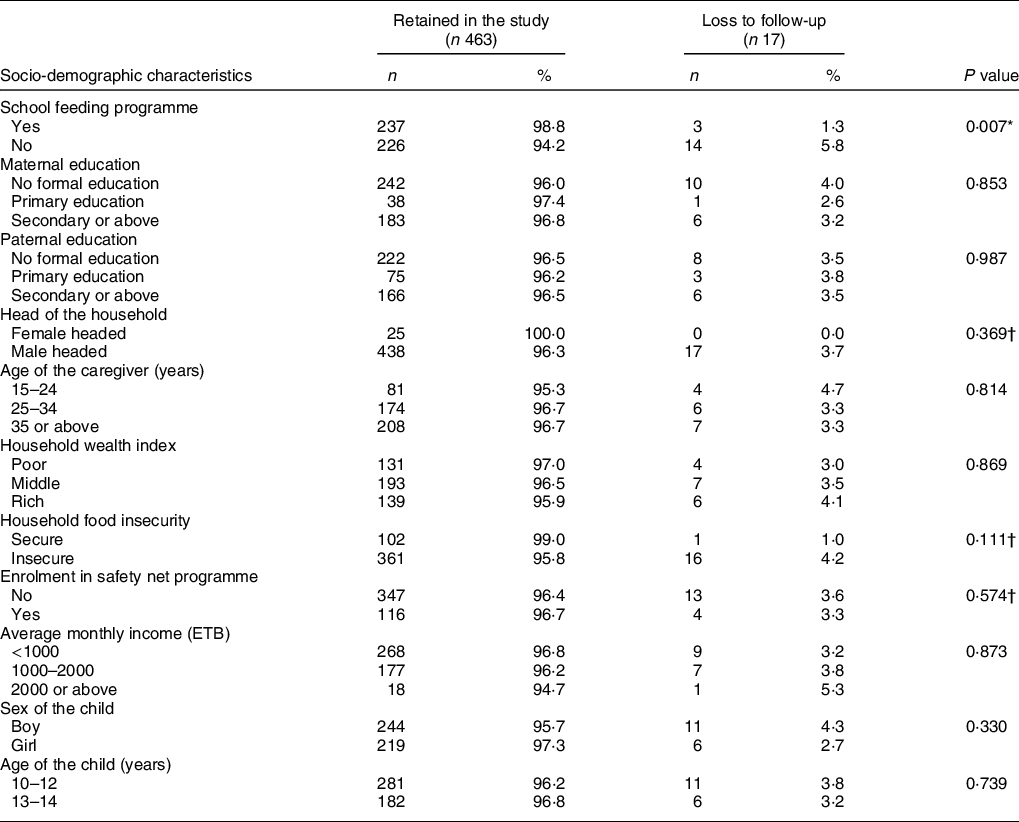

School attendance and academic performance

Data on school attendance and academic performance were available for 463 children (237 SFP beneficiaries and 226 non-beneficiaries). Children retained (n 463 (96·4 %)) and lost to follow-up (n 17 (3·5 %)) were not significantly different in basic socio-demographic and economic characteristics except enrolment status in SFP (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison of the basic characteristics of children lost to follow-up and retained in the study, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

ETB, Ethiopian birr.

* Significant difference at P value of 0·05.

† Fisher’s exact test; others χ 2 test.

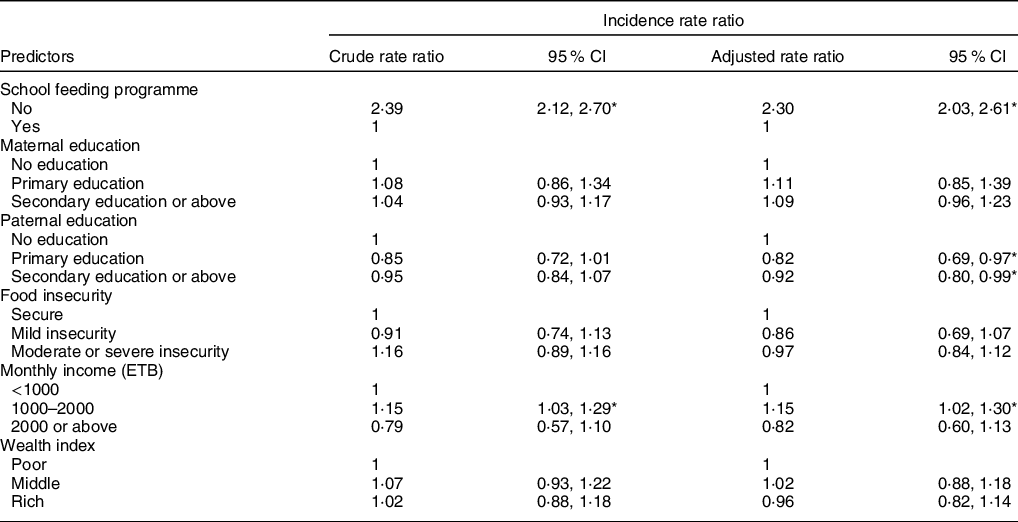

The mean (sd) number of days children were absent from school was 4·0 (sd 1·5) and 9·3 (sd 6·0), among SFP beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (t = 13·524, P < 0·001). The medians (interquartile range) of number of days of absenteeism were also 4·0 (interquartile range = 2) and 8 (interquartile range = 9), respectively, for the two groups. In the multivariable negative binomial model adjusted for five possible confounders, schoolchildren who were not covered by the SFP had two times (adjusted rate ratio = 2·30 (2·03–2·61)) greater risk of class absenteeism than their counterparts (P < 0·001) (Table 4).

Table 4 Association between enrolment in school feeding programme and school absenteeism, in Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

ETB, Ethiopian birr.

* Significant association at P value of 0.05.

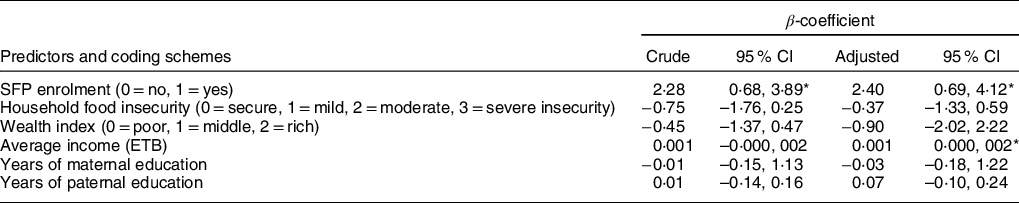

Among SFP beneficiary children, the average (sd) score (%) for ten courses taken in the academic year (63·8 (sd 8·8)) was significantly higher than the corresponding figure among non-beneficiary students (61·5 (sd 7·7)) (t = 2·973, P = 0·003). In the multivariable linear regression model, a significant but small mean difference of 2·40 (0·69–4·12) percentage points was observed in favour of SFP beneficiaries (P = 0·006) (Table 5).

Table 5 Association between enrolment in school feeding programme and academic performance among schoolchildren in Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

ETB, Ethiopian birr.

* Significant association at P value of 0·05.

Discussion

The study demonstrated that the SFP, which is primarily implemented as a targeted social protection intervention, advances multiple educational outcomes among socio-economically disadvantaged children in Southern Ethiopia. School feeding substantially reduced dropout and class absenteeism of children and improved academic scores. The finding suggests that scaling up the SFP to other food insecure settings would serve as an instrument for advancing multiple education and learning outcomes.

We observed that the school dropout rate over an academic year was almost six times higher among non-SFP beneficiary children. A study in Borcha district, Southern Ethiopia, found slightly lower dropout rate in SFP beneficiary schools (0·9 %) than the non-beneficiaries (1·7 %)(Reference Zenebe, Gebremedhin and Henry14). Similarly, in Bangladesh, provision of a mid-morning snack at schools reduced the chance of dropping out of school by about 8 %(Reference Ahmed21). According to a study in Ghana, the national SFP has contributed significantly for improving pupils’ retention compared with the period before the initiation of the programme(Reference Yendaw and Dayour22). In drought-affected areas covered by SFP, children who otherwise dropout of school for various reasons may stay in school with the intention of maintaining access to school meals.

The study found that non-beneficiary children had two times increased probability of missing classes than their counterparts and the SFP increased class attendance by approximately 5 d over the year. The finding is supported by studies conducted in Ethiopia and other low- or middle-income countries(Reference Zenebe, Gebremedhin and Henry14,Reference Ahmed21–Reference Jacoby, Cueto and Pollitt25) . A comparative cross-sectional study from Southern Ethiopia reported significant differences in school absenteeism rates among beneficiary (1·3 d) and non-beneficiary children (2·6 d) in the 2 weeks prior to the survey(Reference Zenebe, Gebremedhin and Henry14). A study from Debere Libanos, Northern Ethiopia, concluded likewise(Reference Assefa23). In Bangladesh, class attendance was increased by 1·3 d/month due to school feeding(Reference Ahmed21). In Jamaica, marginal improvement in attendance rates was observed among children receiving school breakfast(Reference Simeon24). In Peru, SFP increased attendance rates by 0·58 percentage points(Reference Jacoby, Cueto and Pollitt25). The findings of these studies imply that in food insecure settings, feeding programmes motivate parents to make sure that their children attend classes regularly.

We observed a significant 2·4 percentage point difference in the average academic performance of the students in favour of the SFP beneficiaries. Similar positive effects were also reported in other low-income settings(Reference Yohannes16,Reference Simeon24,Reference Chakraborty and Jayaraman26–Reference Metwally, El-Sonbaty and El Etreby29) . A study in Addis Ababa showed that the SFP had a small but positive effect on academic achievement of students(Reference Yohannes16). Studies from Jamaica(Reference Simeon24), India(Reference Chakraborty and Jayaraman26) and Uganda(Reference Alderman, Gilligan and Lehrer27) concluded likewise. SFP may improve school performance of vulnerable children through multiple pathways including improving class attendance and motivation, alleviation of hunger and promoting attention span. School feeding may also improve cognitive functions including memory at schools especially among undernourished children(Reference Jomma, McDonnell and Probart2,Reference Grantham-McGregor, Chang and Walker28,Reference Metwally, El-Sonbaty and El Etreby29) . Despite the fact that the 2·4 percentage point difference in the average academic performance between the two groups is statistically significant, it is important to note that the effect size is small and the practical significance of the difference is likely to be limited.

The major strength of this study is that it employed a prospective cohort design and thus is less likely to be affected by systematic errors than the existing cross-sectional studies previously conducted in Ethiopia. We have also taken multiple educational and learning outcomes into consideration including dropout, absenteeism and academic performance. However, the following limitations should be taken into consideration. As the study was not a randomised trial, systematic baseline differences between the two groups cannot be excluded. For instance, as schools were enrolled into SFP based on severity of food insecurity in their catchment area, SFP beneficiaries are more likely to be from socio-economically disadvantaged families. This may result in underestimation of the effect of the SFP because such children are more prone to dropout, absenteeism and poor academic performance than those from better-off families. Though we have attempted to statistically offset socio-economic differences between the groups, residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Another limitation is that we did not assess the effect of school feeding separately among undernourished children due to sample size concerns. Previous studies suggested the educational and learning benefits of school feeding tend to be larger among malnourished children(Reference Jomma, McDonnell and Probart2,Reference Grantham-McGregor, Chang and Walker28) . Furthermore, we only followed the students for one academic year and were not able to evaluate the long-term benefits of the intervention. Finally, while we evaluate the effect of SFP on the academic performance of students, we only considered the aggregated academic results of the students and did not treat the score for each subject as a distinct outcome variable. This was because we had no strong reason to assume that the effect of the programme would vary across different subjects.

Conclusion

School feeding substantially reduced dropout and absenteeism of socio-economically disadvantaged schoolchildren and improved academic scores. Scaling up the programme to other food insecure settings may yield multiple educational and learning benefits.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to all study participants, data collectors and supervisors involved in the study. Financial support: The study was supported by Hawassa University – Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) programme. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: T.A.D. implemented the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. S.G. formulated the research question, designed the study, supervised the study and finalised the manuscript. F.R.A. formulated the research question and designed the study. B.J.S. formulated the research question, designed and supervised the study and finalised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version for submission. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the institutional review board of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Hawassa University. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.