Head Start (HS) is the largest federally funded early childhood education programme in the USA, serving low-income, limited resource, 3–5-year-old children and their families(1). HS reaches more than 1 million children each year making it an ideal setting for implementing obesity prevention programming among children and families who are at increased risk(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,3) . Prior literature has suggested children enrolled in HS are more likely to be obese compared with the general population of preschool-aged children(Reference Tarullo, West and Aikens4). Additionally, a recent study reported that, compared with non-HS preschoolers, 3-year-old children who entered HS with an unhealthy weight status were significantly more likely to enter kindergarten at 5 years of age with a healthy BMI(Reference Lumeng, Kaciroti and Sturza5).

HS began in 1965, when obesity was not common among children, but federal founders of the programme understood the importance of children’s physical health and its influence on their social competence and capacity to learn. As a result, policies addressing prevention of overweight/obesity were embedded within the HS infrastructure(Reference Zigler, Piotrkowski and Collins6). While the Program Performance Standards (PPS) and federal regulations governing HS programmes focus on core developmental domains such as cognitive and socioemotional development, HS programmes are also required to provide programming focused on health and offer meals, snacks and nutrition education(1). It has been theorised that this comprehensive approach to promoting school readiness and health is the reason for observed positive effects on nutrition and physical activity (PA) practices among young children in HS environments(Reference Ritchie, Boyle and Chandran7–Reference Dev and McBride9). Responsible for implementing many of the childhood obesity prevention-related PPS, HS teachers are key partners for expanding efforts to encourage healthy lifestyles among children and families(Reference Benjamin-Neelon10,Reference Lumeng, Kaplan-Sanoff and Shuman11) . Unfortunately, while teachers express the importance of practicing healthy eating and PA behaviours for themselves and the children and families they serve, determinants at the individual, social, economic and environmental levels may impact teachers’ efforts to change their own health behaviours and promote healthy eating and PA in their classrooms(Reference Lynch and Batal12,Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13) .

Due to the large amount of time children spend at school, teachers’ impact on children’s healthy eating and PA levels may be as influential as children’s parents(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14,Reference Larsen, Hermans and Sleddens15) . Unfortunately, early childhood teachers may not eat healthy foods and exercise in their personal lives(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14) calling into question teachers’ ability to effectively role model positive health behaviours to the children and families they serve. High levels of overweight and obesity (> 70 %) exist among HS teachers(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,Reference Song, Song and Nieves16) . Potentially related intake among early childhood teachers includes low intakes of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables, high intake of unhealthy foods and beverages (e.g. sugar sweetened beverages, fried foods)(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,Reference Song, Song and Nieves16) and high levels of sedentary behaviours (4 and 8·6 h/d)(Reference Shen, Mao and Liu17,Reference Thorp, Owen and Neuhaus18) . Some researchers have theorised when teachers realise the importance of their own health behaviours and are provided with appropriate training, they may be better able to successfully model and promote positive health behaviours in their classrooms(Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein19,Reference Derscheid, Umoren and Kim20) . For example, a teacher who is working to improve their own personal eating behaviours may be more likely to role model healthy eating for children in their care(Reference Lebron, Ofori and Sardinas21). However, other researchers have questioned this theory stating an improvement in teachers’ knowledge may not necessarily translate into improved teaching practices(Reference Lanigan22,Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride23) .

Teachers who implement best practices in the classroom, such as enthusiastically role modelling healthy eating, providing nutrition education and avoiding food-based rewards, can help children choose healthier foods when the foods served are of high nutritional value(Reference Ward, Blanger and Donovan24). However, contextual factors may support or work against teachers’ ability to implement these best practices. At the individual level, teachers’ personal health behaviour and status(Reference Song, Song and Nieves16,Reference Ward, Blanger and Donovan24) , knowledge and attitudes(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13,Reference Lanigan22,Reference Dev, McBride and Speirs25–Reference Nahikian-Nelms28) and cultural background(Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride23,Reference Freedman and Alvarez29) may influence teaching practices. At the social level, families may serve as a significant barrier(Reference Fees, Trost and Bopp30–Reference Taveras, LaPelle and Gupta34) leaving some teachers to feel frustrated and discouraged when parents do not support efforts to promote the healthy behaviours learned at school in the home environment. Finally, at the environmental level, policies, staff knowledge and training opportunities, limited time, material resources and funding can also work in support or against teacher efforts to implement best practice in their classrooms(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13,Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride23,Reference Carraway-Stage, Henson and Dipper35–Reference Lisson, Goodell and Dev37) .

Childhood obesity prevention programmes often rely on early childhood teachers to implement the programme because they are responsible for teaching nutrition education curricula and encouraging healthy eating among children across diverse learning environments(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2). Teachers who place emphasis on their own personal health and PA levels may be more likely to promote those same behaviours in their classroom, thus positively affecting child health(Reference Derscheid, Umoren and Kim20,Reference Esquivel, Nigg and Fialkowski38) , but more research is needed to explore the specific determinants that influence teachers’ personal and professional healthy eating and PA behaviours. To date, several studies have separately explored factors that may impact teachers’ personal(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14,Reference Song, Song and Nieves16,Reference Linnan, Vaughn and Smith39) and professional(Reference Lynch and Batal12,Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13,Reference Tovar, Mena and Risica40,Reference Mita, Gray and Goodell41) health behaviours at individual, social and environmental levels. However, to the author’s knowledge, only one quantitative study has come close to exploring teachers’ personal and professional experiences simultaneously(Reference Halloran, Gorman and Fallon26). Further, most qualitative studies are focused on identifying factors influencing the implementation of specific classroom practices, e.g. mealtime, with few studies focusing on understanding the role of the broader context such as personal healthy eating belief and its influence on classroom practices(Reference Lynch and Batal12,Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14,Reference Halloran, Gorman and Fallon26,Reference Mita, Gray and Goodell41) . Taken together, more research is needed to understand the specific determinants that influence teachers’ personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and physical activity. Exploring these factors simultaneously is also needed in order to support an understanding of potential interrelationships between the two socio-ecological structures. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to qualitatively explore teachers’ personal and professional socio-ecological structures while examining HS teachers’ experiences with (1) trying to eat healthy and engage in PA and (2) promote healthy eating and PA in their classrooms.

To provide context for exploring these factors, partners from two North Carolina (NC)-based HS organisations collaborated to implement the evidence-based, hands-on intervention, Families Eating Smart and Moving More (FESMM), with the goal of educating HS teachers to improve their personal healthy eating and PA behaviours. FESMM was developed by NC Cooperative Extension at NC State University and the NC Division of Public Health and is an evidence-based, hands-on intervention targeting the four impact goals of the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP): (1) improve diet quality and PA of the family; (2) improve food resource management skills; (3) improve home food safety practices and (4) decrease food insecurity. Interactive nutrition education sessions were developed based on a community needs assessment of current diet and PA behaviours, food resource management skills, food safety practices and food security practices among low-income, low-resource adults living in NC(Reference Jones, McDonald and Stage42). Each of the six 45 min lessons included food experiences, tastings, demonstrations and opportunities to practice simple PA and hands-on activities to engage participants and increase targeted skills.

Methods

Research design

Researchers used in-depth, semi-structured interviews to examine NC HS teachers’ personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and PA. Researchers designed data collection and analysis methods using a phenomenological approach – a qualitative method that studies common experiences among a group of individuals(Reference Jones, Dunn and Foley43,Reference Moustakas44) . All study materials were approved by East Carolina University’s Institutional Review Board.

Sampling and participants

Researchers utilised purposive criterion sampling to identify eligible teachers across seven centres in two rural eastern NC counties. This method of sampling ensured the creation of a homogenous sample of participants who all experienced the same phenomenon(Reference Jones, Dunn and Foley43–Reference Creswell45). Study inclusion criteria required teachers to be 18 years or older, employed by a NC-based HS programme located in one of two counties in eastern NC, and have completed the EFNEP FESMM curriculum, to ensure teacher participants had prior experience with trying to improve their personal healthy eating and PA behaviours. See Table 1 for additional details.

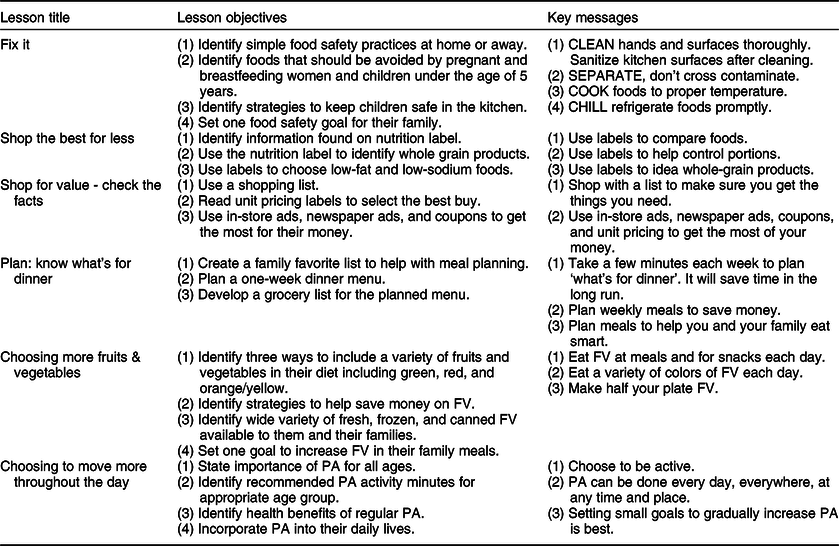

Table 1 Eating smart and moving more 6-lesson series content*

* Lessons where 30–45 min in length and focused on engaging teachers in food experiences, tastings, opportunities to practice simple physical activity, and hands-on activities to engage participants. The series focused primarily on improving teacher’s personal health behaviours and not professional development on how to teach children or families about making healthy eating and physical activity behaviour changes.

Recruitment

At the beginning of the FESMM curriculum, teachers were informed about the opportunity to participate in in-depth telephone interviews that would occur at the end of the programme. Researchers recruited eligible teachers to participate in the interviews by attending the last FESMM lesson, distributing flyers and directly emailing teachers within each HS centre. Researchers also asked partnering HS Health/Nutrition Coordinators to distribute information about the study to teachers in their respective centers.

Data collection and protocols

Researchers developed a semi-structured interview guide featuring a verbal script and interview questions with probes (Table 2). Three trained researchers conducted telephone interviews between March and June 2017. Prior to the beginning of data collection, interviewers were trained in human ethics and qualitative research methods using the Goodell 5-Phase Protocol for training interviewers(Reference Hall, Chai and Albrecht46). This process also served to pilot test the interview guide. Teachers who expressed interest in participating in an interview were contacted via email to schedule an interview time and share a copy of the consent form for review. At the beginning of the interview, the interviewer read the consent form to the participant and obtained verbal consent. The interviewer then signed a hard copy of the consent form on behalf of the participant and returned a scanned copy of the signed document to the participant via email (or mail if requested).

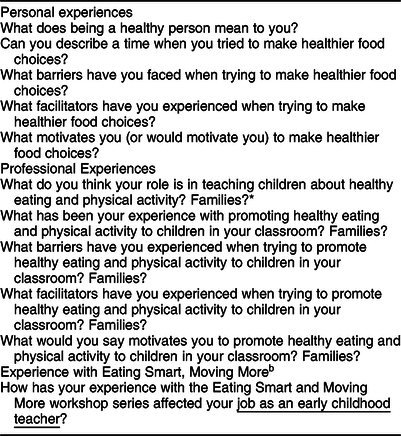

Table 2 Primary in-depth interview questions for Head Start Teachers participating in data collection on teacher’s’ experience with improving their personal healthy eating and physical activity and promoting healthy eating and physical activity in their classroom

* Interviewers were trained to probe further if a participant did not fully answer a question (e.g. addressed their role in teaching about healthy eating, but not physical activity).

During the 45–60 min interviews, researchers encouraged teachers to share their personal experiences/stories related to improving their personal health and their past experiences with promoting healthy eating and PA among children and families. Researchers recorded all interviews in digital audio format. An independent transcription service transcribed the recordings verbatim. As data were collected, the principal investigator engaged in preliminary open coding in order to track saturation. Data collection continued until saturation was achieved(Reference Goodell, Stage and Cooke47). A minimum of ten interviews has previously been cited as appropriate within phenomenological study designs where saturation is achieved(Reference Moustakas44,Reference Creswell45) .

Researchers utilised several techniques to ensure trustworthiness. Strategies included maintaining detailed notes and memos for each interview, audio recordings, peer debriefing, member checking, bracketing to identify potential researcher bias and triangulation of data with HS partners(Reference Bowen48). To triangulate findings, final themes were sent to each participating teacher for review. Teachers were asked to review and reflect on the accuracy of a summary of their individual interview and major identified themes. While only three teachers responded to the request, all reported the summary and themes provided accurately reflected their perspectives and experiences(Reference Creswell45,Reference Bowen48) .

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 22.0 was used to analyse descriptive statistics for basic demographic information. Researchers utilised phenomenological methods to guide data analysis following Moustakas’s structured method for inductive data analysis(Reference Jones, Dunn and Foley43). The principal investigator and one research assistant read all transcribed interviews twice to immerse themselves in the dataset. The team read the transcripts a third time focusing on memoing, development of a coding template and identification of key themes(Reference Jones, Dunn and Foley43). Researchers followed four steps for the in-depth analysis. First, the analysis team developed a list of significant statements about the participants’ experience with the programme (Step 1). Next, the team reduced and eliminated statements that did not represent details necessary for understanding the participant experiences (Step 2). Codes were clustered and reduced into eighteen themes representing teachers’ experiences with the phenomenon of interest (Step 3). Finally, the principal investigator confirmed the presence of each theme by rereading complete transcripts to ensure identified themes accurately represented participants’ words (Step 4). Themes were used to describe ‘what’ was experienced and ‘how’ it was experienced. Written descriptions were used to construct the overall ‘essence’ of teachers’ experiences(Reference Jones, Dunn and Foley43,Reference Moustakas44) .

Results

Participants

Researchers completed fifteen in-depth interviews with HS teachers. Saturation was achieved at nine interviews; however, data collection continued until fifteen to ensure no new information would be obtained with additional interviews. Teachers were 100 % female, an average age of 43 years (sd 9·6) and Black/African American (93·3 %) or Latino (6·7 %). Teachers had 9·9 years (sd 8·1) of teaching experience. A total of 26·7 % of teachers reported they had a 2 year Associates degree and 40 % a 4 year degree in Early Childhood Development.

In-depth interview results

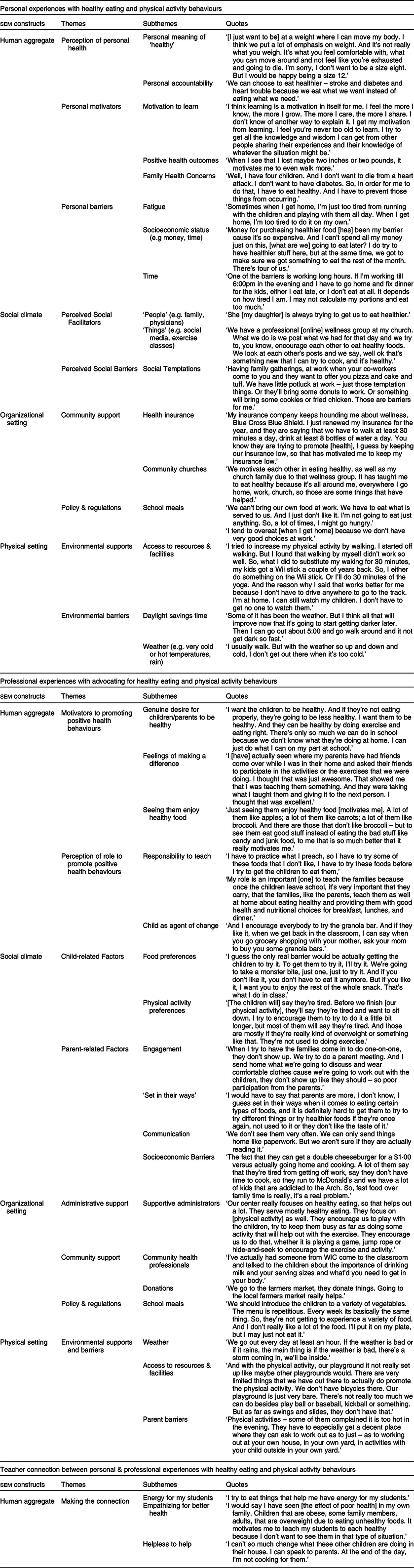

Researchers identified eighteen primary themes related to teachers’ experiences when trying to improve their personal health behaviours and professionally promote healthy eating and PA in their classrooms (Table 3). To better understand the dynamic interrelationships between individual, social and environmental influences on teacher behaviour, researchers inductively organised themes and subthemes under teachers’ personal and professional experiences by the Theory of Social Ecology constructs(Reference Shenton49). The theory identifies four influences related to behaviour including Human Aggregate (e.g. sociocultural characteristics of individuals); Social Climate (e.g. the supportiveness of a social setting); Organizational Setting (e.g. worksite, school) and Physical Setting (e.g. weather and built environments) (Table 3). Finally, researchers explored the interrelationship between teachers’ personal and professional social ecological structures as a separate emergent theme. Figure 1 visually represents the identified themes within the theoretical model.

Table 3 Supportive Head Start Teacher quotations for themes and sub-themes aligned with the theory of social ecology constructs (n 15)

Teachers’ personal experiences with healthy eating and physical activity

Human aggregate

Teachers described sociocultural characteristics that influenced their healthy eating and PA behaviours including their Perception of Personal Health, Personal Motivators and Personal Barriers. When asked to describe what being ‘healthy’ meant to them, teachers described personal health issues (e.g. blood pressure, obesity), physical feelings related to health (e.g. pain, weight status) and/or their philosophy of being healthy (e.g. ‘healthy does not mean being a size four’). The majority of teachers expressed that it was their responsibility to take care of their own health and recognised the importance of learning to lead a healthy lifestyle to prevent disease and/or extend their lifespan.

Teachers generally acknowledged the need to improve their own health behaviours and were motivated by opportunities to learn how. Several teachers stated centre-level activities intended to teach children and families about positive health behaviours were also opportunities for them to learn about healthy lifestyle choices. Most teachers also frequently commented on improving their health to ensure that they could live a long life and/or to ensure they could ‘be there’ for their families. One teacher stated, ‘I want to be able to see my babies have babies and be able to play with those babies. If I continue the path that I’m on, I’m not going to be able to see them grow up’.

Despite describing numerous motivators, teachers also recognised personal barriers to making healthy choices such as fatigue, socio-economic factors and limited time. Some teachers described being too tired to make healthy choices, such as preparing a healthy meal or engaging in PA after work. Teachers described facing similar socio-economic barriers as their HS families, frequently stating that being low income themselves influenced their ability to purchase fruits and vegetables and afford adequate childcare that might support their ability to be more physically active after work. Teachers also described how their busy schedules limited their time to prepare meals at home and/or have sit down family meals often leading to a reliance on fast food.

Social climate

Social characteristics that reportedly affected teachers’ personal healthy eating and PA behaviours were Perceived Social Facilitators and Perceived Social Barriers. Teachers described ‘people’ as supportive of their ability to make positive personal health choices including family members, friends, physicians, fitness instructors and/or their church community. Teachers also described ‘things’ they considered supportive of their personal healthy eating and PA behaviours including health-focused discussion boards/social media with friends (particularly those that share healthy recipes), exercise videos, listening to music during exercise, fun exercise classes and educational opportunities to learn about healthy eating and PA. Social barriers were less frequently described but often centred on temptations to eat unhealthy foods at home and/or social functions at church.

Organisational setting

Organisational characteristics that impacted teachers’ personal dietary and PA behaviours were identified as Community Support and Policy & Regulations. Teachers mentioned community support, such as health insurance wellness initiatives and community churches, as helpful towards helping them making positive health choices. Several teachers discussed the importance of a culture of health in their everyday life to provide support and encouragement for making healthy choices. Policy and regulations were also reported as influential on teachers’ health behaviours, particularly those related to the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) and the HS PPS that require teachers to eat what is served to children. One teacher commented ‘(When I don’t like what is served), I don’t eat anything. A lot of times I just go hungry. When I get off work I tend to overeat because I am so hungry. We don’t have good choices at work’. Teachers expressed concern over the meals being served, often describing the types of foods offered during meals as being of poor nutritional quality and/or limited in variety. These issues created challenges for teachers who were attempting to make healthy dietary choices for themselves.

Physical setting

Characteristics of the natural and built environment that reportedly impacted teachers’ personal healthy eating and PA behaviours were identified as Environmental Supports and Environmental Barriers. Teachers described having access to resources (e.g. activity-based video games) and/or facilities (e.g. access to a gym or walking trail) where they could engage in PA, facilitated their ability to make healthy choices. However, barriers were also described such as daylight savings time and weather.

Teachers’ professional experiences with advocating for healthy behaviour and physical activity

Human aggregate

Sociocultural characteristics that reportedly impacted teachers’ ability to professionally promote healthy eating and PA behaviours among children and families were identified as Motivators to Promote Positive Health Behaviours and Perception of Role to Promote Positive Health Behaviours. All teachers described their genuine desire for children in their classroom to be healthy, feelings of making a difference and seeing children enjoy healthy foods as motivators for promoting positive health behaviours in their classrooms. Most teachers stated that they were also motivated to teach parents about positive health behaviours so that they can serve as role models to their children. Several teachers described feeling like they were ‘making a difference’ helped motivate them to continue teaching children and parents about leading a healthy lifestyle. Most teachers agreed they felt an ‘obligation’ or ‘responsibility to teach’ children and families about making positive health behaviour choices. Approximately half of the teachers described using children as an agent of change for their families by encouraging them to ask their parents to purchase healthy foods. However, other teachers expressed a helpless feeling related to their ability to successfully influence children and/or families health behaviours.

Social climate

Social characteristics that reportedly impacted teachers’ ability to promote healthy eating and PA behaviours were categorised as Perceived Child-related Factors and Perceived Parent-related Factors. Child-related barriers included children’s fear of trying new foods and children’s disinterest in being physically active. All teachers described difficulty in trying to get children to try new foods citing limited prior exposure to healthy foods at home. However, most were able to describe strategies for overcoming these barriers such as using food-based learning experiences, utilising menus and mealtimes for discussion about positive health behaviours, encouraging children to try new foods including the ‘one bite’ rule, role modeling and integrating learning with other subjects (e.g. dental health). Teachers also described children not wanting to engage in physical activities during the day because they are ‘tired and want to sit down’. A few teachers felt the lack of interest in PA among some children may have been due to being overweight. Teachers described strategies for encouraging children to be physically active as role modelling and using music.

Parents presented several social challenges including engagement, communication, and cultural and socio-economic barriers. Some teachers described having difficulty promoting positive health behaviours to families due to lack of parent engagement. Reasons for limited parent engagement often included busy work schedules and/or family transportation challenges. Most teachers expressed concern over the limited communication they have with parents throughout the year. Some children ride a bus to and from school, meaning a teacher would have little to no contact with parents over the school year. These teachers also reported barriers to interacting with parents who drop-off or pick-up their children from school, stating they found it difficult to supervise children in their classroom while trying to hold meaningful conversations with parents about health behaviours.

Many teachers felt parents/families were unwilling to change their personal health behaviours at home because they are ‘set in their ways’, referencing challenges related to cultural and/or generational influences. Teachers also felt that families’ economic status presented greater challenges to making positive health choices, including limited time and/or energy to prepare meals at home and/or have sit down family meals. Teachers perceived parents were more likely to make poor dietary choices by purchasing quick foods (e.g. fast food) and/or giving children ‘bad food’ that they like to eat out of convenience. Despite these challenges, teachers also described parent-focused strategies such as inviting parents to engage in healthy eating and PA opportunities at school (e.g. sharing a meal, family fun nights, attending a planned classroom activity), sending home information (e.g. flyers in backpacks, menus/recipes), participating in home visits and working to establish a strong rapport with parents in an effort to facilitate communication about healthy eating and physical activities.

Organisational setting

Organisational characteristics that reportedly impacted teachers’ professional healthy eating and PA advocacy behaviours were described as Administrative Support, Community Support and Policy & Regulations. Teachers described administrative support in their programmes as encouraging teacher–child play, including nutrition education and PA in their lesson plans, and providing healthy meals. However, some teachers discussed having limited time available to concentrate on nutrition education topics due to other instructional requirements. Community support came from local health professionals coming in to teach children about nutrition and PA and in the form of fruit/vegetable donations for food tastings. Finally, policies and regulations were cited as organisational characteristics that reportedly impacted teachers’ efforts to promote positive health behaviours. Teachers described not being able to bring in outside food into the classroom and having a lack of control over the foods being served. Many teachers expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of meals served. One teacher commented, ‘We can’t bring our own food to work; we have to eat what is served to us. Even though I try to promote it to the kids, I just don’t like it’.

Physical setting

Characteristics of the natural and built environment that reportedly impacted teachers’ professional healthy eating and PA advocacy behaviours were described as Environmental Supports and Barriers. Teachers commonly described the weather as influencing the type and environment for PA. For example, a rainy day meant that children must engage in physical activities indoors v. outside. Some teachers discussed having access to indoor child-size exercise equipment that children could play on when the weather is not suitable; however, other teachers reported they did not have access to these types of resources. Finally, teachers reported parents often describe their home environments as being a barrier to engaging in healthy eating and PA. For example, when the weather is too hot or they do not have a place to exercise and/or play safely, it limits opportunities for PA.

Making the connection between personal health experiences and professional health promotion

Finally, teachers described connections between their personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and PA. Connections directly acknowledge by teachers included Energy for my Students, Emphasizing for Better Health and Helpless to Help. Approximately half of the teachers made clear connections between their own health behaviours and classroom practices. These factors were only observed at the Human Aggregate level of the Theory of Social Ecology (Table 2). Several teachers described the importance of making positive dietary and PA choices so they would ‘have energy to keep up with my students’. One teacher stated she had observed how eating poorly affected her physical health. This negative experience motivated her to promote healthy eating and PA among the children in her classroom because she did not want to see them ‘in the same type of situation’. Many teachers also expressed a desire for children and families to be healthy so that they would not have to face the same challenges the teachers personally faced and described the FESSM as helpful towards achieving this goal. One teacher stated, ‘(FESSM has) helped me give information where it’s needed to parents and even to coworkers. We still talk about our classes that we had. (It has helped us a lot) to get information to our parents. And we talk to our children about how healthy it is to eat good things’.

Not all teachers made a connection between their health behaviours and their classroom practices. When asked directly about how participating in the FESSM intervention impacted their classroom practices, one teacher stated, ‘I don’t think it has yet, I don’t think more than I normally would do prior to taking the class’. Similar statements were made by a small number of teachers. These teachers were more likely to state they felt parents had a greater influence on the children than they did, and often described how parents worked against their efforts by not engaging in health promotion activities offered by the teacher and or promoting negative health behaviours. Several teachers cited a helpless feeling when it came to encouraging children and families to change their health behaviours. Poor parent contact and communication throughout the year appeared to make this situation worse.

Discussion

This study conducted a qualitative exploration of HS teachers’ lived experiences with (1) trying to eat healthy and engage PA and (2) promote healthy eating and PA in their classrooms (Fig. 1). Study findings provide unique insight into individual, social and environmental determinants that may influence teachers’ health behaviours and health promotion practices after participating in a healthy eating and PA intervention. Further, the study explores the interrelationship between the personal and professional social ecological structures as directly acknowledge by teachers’ themselves.

Fig. 1 Theoretical model presenting relationships between Head Start teachers’ (n 15) individual, social, and environmental influences

Personal experiences with healthy eating and physical activity

Teachers expressed a desire to make positive health choices, recognising the impact their decisions had or would have on their health and their family members. Similarly, teachers described taking responsibility for their health and health behaviours and were motivated to learn how to improve them(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2). Therefore, teachers were also eager to serve as positive role models for children in their immediate family. Unfortunately, while teachers’ overall outlook towards making positive health choices were optimistic, prior research has indicated that they may need more support in this area as evidenced by limited personal nutrition knowledge and struggles with healthy eating(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13) .

When compared with women from similar socio-demographic backgrounds, HS teachers are more likely to be overweight or obese(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2,Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride23) , have higher rates of diabetes and high blood pressure, and poor mental health(Reference Whitaker, Becker and Herman27). While HS teachers may be motivated to serve as positive role models, their own health behaviours may first need improvement(Reference Moos, Cohen and Adler50). Our findings add to the literature suggesting HS teachers are optimistic and motivated to make positive health choices; however, it is important to remember that teachers who participated in this study had recently completed the FESMM intervention. As a result, teachers may have felt more confident in their personal nutrition knowledge and may have been more motivated to make positive health choices at the time of their interview compared with teachers interviewed in prior studies.

For HS teachers, our findings suggest that social and environmental influences play an important role in their everyday personal health choices. For example, teachers often discussed the socio-economic barriers they faced when trying to make positive dietary and PA choices. Like the background of HS families, teachers are likely to be low income(Reference Sharma, Dortch and Byrd-Williams2). In addition to modest pay, early childhood positions also often include limited benefits such as paid sick and vacation time(Reference Ward, Vaughn and Story51,Reference Carson, Baumgartner and Matthews52) . Teachers’ shifts are frequently long and structured, often not allowing for the flexibility to meet personal needs such as seeking health care(Reference Lessard, Wilkins and Rose-Malm53). These factors can lead to high absenteeism, employee turnover and burnout(Reference Ward, Vaughn and Story51). A recent review of the health status of childcare workers further revealed teachers personally struggle with healthy eating, PA and mental health (stress and depression)(Reference Carson, Baumgartner and Matthews52). Early childhood teachers reportedly face many additional barriers when it comes to making positive dietary and PA choices including being tired at the end of the day, having limited time and numerous after-work responsibilities (e.g. caring for own child, preparing meals)(Reference Lessard, Wilkins and Rose-Malm53). Taken together, these challenges can serve as a roadblock for teachers intending to make positive health behaviour choices, as well as their ability to effectively promote healthy eating among young children(Reference Benjamin-Neelon10,54) .

Teachers also often described they were more successful when environmental supports were available to help support their choices to make positive health behaviours. For example, teachers described having support systems through family, friends or local community groups that helped them remain accountable and encouraged them continue making positive choices. A potential missed opportunity may be the use of the workplace setting to provide teachers with a prospect for both individual-level behaviour and environmental change. Past research has demonstrated that dietary behaviours can be positively impacted through employee wellness programmes that focus on education and healthful modifications in the work environment(Reference Whitaker, Dearth-Wesley and Gooze55–Reference Tamers, Beresford and Cheadle61). A few prior studies have explored the promising approach of employee wellness programmes in the preschool setting(Reference Esquivel, Nigg and Fialkowski38,Reference Sorensen, Linnan and Hunt59,Reference Gosliner, James and Yancey60) ; however, findings are mixed. Esquivel and colleagues found positive results after implementing the Children’s Health Living Program, a multi-component intervention that included an employee wellness component, in twenty-three HS classrooms (eleven intervention, twelve delayed intervention). Teachers reported improvements in PA levels, weight control, dietary behaviours, skills and knowledge about nutrition(Reference Esquivel, Nigg and Fialkowski38). However, Linnan and colleagues reported less promising outcomes for Caring and Reaching for Health (CARE), a multi-level, theory-guided intervention designed to improve early childhood teachers’ PA (main outcome) and several other health behaviours (e.g. diet, stress). The intervention was not successful at improving teachers’ PA levels, but researchers did observe significant improvements in dietary outcomes (e.g. fruits and vegetables, sugar sweetened beverages). These significant differences were no longer observed after controlling for multiple comparisons. In post-interviews with teachers, participants expressed a desire for more personal or ‘high-touch’ interactions including more personal communication such as text messaging and in-person events with coworkers and/or research staff(Reference Linnan, Vaughn and Smith39).

Utilising employee wellness programmes within HS programmes may be a chance to effectively create the culture of health teachers in the current study described as being an important facilitator of their choice to personally practice and professionally advocate for positive health behaviours. However, more research is needed to explore the efficacy of implementing a wellness programme in the HS setting, including evaluation of the National Head Start Association’s Nurturing Staff Wellness toolkit, a seven-step guide designed for HS programmes interested in implementing a wellness programme(Reference Gosliner, James and Yancey60). Future research should also identify and reduce organisational and environmental barriers to change, address social contextual factors that drive behaviours and build expanded networks of community partnerships that may be supportive of employee wellness programming(Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein19,Reference Whitaker, Dearth-Wesley and Gooze55) .

Professional experiences promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviours among children and families

Teachers in our study reported that they had a responsibility to provide education about healthy eating and PA to the children and families they serve. Similar findings have been observed in other studies with preschool teachers reportedly perceiving themselves as ‘parents at school’ and expressing a desire to positively impact children’s current and future well-being(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14,62–Reference Tucker, Irwin and He64) . Recognising children as potential agents of change, current study teachers often reported that they encouraged children to ask parents about buying healthy foods or doing physical activities at home. All teachers described challenges with getting children to try new foods. Preschool children’s willingness to try new foods is impacted by several factors including neophobia (‘unwillingness to eat novel foods’) and pickiness; both are common among preschool-aged children(Reference Shriver, Hildebrand and Austin65). Interestingly, teachers in the current study were able to describe several evidence-based strategies for overcoming this challenge indicating they felt prepared to address the issue when it arose in their classroom.

Like the findings of Derscheid(Reference Song, Song and Nieves16), Ajja(Reference Galloway, Lee and Birch66) and Swindle(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14), teachers also often described menus as a barrier to health promotion in their classroom. Teachers expressed a lack of control over menu items served. Teachers reported food items featured on menus not only impacted their ability to promote healthy foods provided during meals and snacks but also inhibited their ability to make healthy dietary choices themselves. Swindle & Phelps(Reference Ajja, Beets and Chandler67) interviewed twenty-eight early childhood teachers (fifteen were employed in HS centres) who also described the foods served during mealtime as unhealthy and/or foods they did not enjoy. These teachers reported using coping skills such as pretending to eat, telling children their physician told them not to eat the food, cutting food into smaller pieces and allowing food to sit in front of them without eating it.

Federal Performance Standards require HS programmes to participate in either the CACFP or the National School Lunch Program(Reference Whitaker, Gooze and Hughes8,Reference Swindle and Phelps68,69) . Andreyeva and colleagues(Reference Swindle, Patterson and Boden70) found that CACFP participating centres demonstrated more positive outcomes related to teacher behaviour during meals (e.g. role modelling, creating a positive mealtime environment)(Reference Dev, Speirs and McBride23,69) , nutritional characteristics of foods served and quality of children’s dietary intake at school. However, our study findings and others(Reference Derscheid, Umoren and Kim20,Reference Andreyeva, Kenney and O’Connel71,Reference Dev and McBride72) suggest HS programmes should consider teacher food preferences and/or teacher participation in the menu planning process as strategy for ensuring promotion of healthy foods served during meals and snacks. Owing to the recent (October 2017) national implementation of the updated CACFP meal pattern requirements, additional studies are needed to determine teachers’ perspectives about trying foods based on the updated requirements. Understanding these issues is critical as teachers may be more likely to serve as positive role models for children in the mealtime setting when foods are ‘healthy and appealing’(Reference Ajja, Beets and Chandler67).

Making the issue more complicated, HS PPS requires teachers to be served the same foods as children during mealtimes (45 CFE 1304·23vii). Prior research has indicated HS teachers not only have lower quality diets but also experience higher rates of food insecurity. HS is currently the only early childhood programme type in the United States that also consistently provides teachers with daily meals and snacks(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14). Researchers have theorised that this policy may be an opportunity to improve dietary quality and food insecurity among HS teachers(Reference Markides, Crixell and Thompson73). However, teachers in our study reported not eating at all throughout the day due to ‘poor quality’ meals (HS policy also prevents them from bringing in outside food), later causing them to overeat. It is unclear whether teacher dissatisfaction with meals being served in the HS centre was related to teacher food preferences, actual poor nutritionally quality of food being served or a mix of both. Regardless, if teachers are consuming less due to these factors, poor quality menus could do more harm than good towards improving teachers’ health behaviours and decreasing rates of food insecurity.

A Health/Nutrition Manager is generally responsible for developing school menus in HS programmes. This individual does not have to be a Registered Dietitian/Nutritionist (RDN) or have a nutrition background, but they must ‘seek consultation from an RDN or nutritionist’ (8 CFE 1302·91iii) for programme support. The degree to which an RDN provides input on the quality of meals served likely varies by HS programme. More research is needed to understand the role of RDN in this capacity, the magnitude of HS programmes who utilise their services and what additional benefits they may be able to provide programmes. CACFP training resources focused on menu development are available for HS programme administrators and teachers at state and federal levels(Reference Loth, MacLehose and Fulkerson74,75) ; however, the extent to which this training is attended, who attends the training and how lessons learned are implemented into menus need further exploration. One study reported <24 % of staff from CACFP-funded centres attended yearly professional development(76), while other studies reported 68 % and 92 % of programmes provide for staff about nutrition, respectively(Reference Halloran, Gorman and Fallon26,Reference Signman-Grant, Christiansen and Fernandez77) .

Finally, teachers reported parent-related challenges, particularly regarding engagement, communication and socio-economic challenges. Prior research has indicated parental influence on children’s behaviour is critical(Reference Gooze, Hughes and Finkelstein78,Reference Alkon, Crowley and Neelon79) . For this reason, parent engagement is a primary focus in HS(Reference Dwyer, Higgs and Hardy80). Federal Program Performance Standards require HS programmes support family engagement in children’s learning and development through parent–child activities, parent education, family goal setting and more(Reference Spinks, Macpherson and Bain81). HS programmes decide locally on how parent engagement will occur. Some programmes may require teachers to do home visits or attend parent meetings, while others do not. The later approach may leave little opportunity for teacher–parent interaction. Similar to findings from Sisson et al., teachers in the current study also expressed concern about the socio-economic status of families and the potential impact on children’s access to healthy foods(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13). Like another study(82), teachers reported sending materials home for parents to read but noted that they do not know if parents receive and/or read these materials. Expert recommendations encourage teacher engagement with parents in promoting positive health behaviours; however, teachers in the current study and others described barriers to promoting positive health behaviours among families when communication channels were related to indirect communication (e.g. handouts) v. direct communication (e.g. in-person meetings, workshops)(Reference Benjamin-Neelon10,Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein19,82–Reference Trost, Messner and Fitzgerald87) . Past studies have also implied teachers may also struggle to communicate information to families about healthy eating and PA due to inadequate personal knowledge and training in the area(Reference Lynch and Batal12,Reference Lindsay, Salkeld and Greaney31–Reference Taveras, LaPelle and Gupta34,Reference Tucker, van Zandvoort and Burke88) , or a fear of offending parents(Reference Taveras, LaPelle and Gupta34).

Further complicating the issue, our study findings also suggest that the level of interaction a teacher has with parents throughout the course of the year is highly variable. This outcome is concerning as teachers in our study and one other have described parent engagement as an important source of teacher motivation. Sisson et al. reported teacher motivation waned and levels of frustration increased when parent support is limited(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13). Effective strategies supportive parent–teacher interaction, and communication is needed in order to improve the promotion of healthy eating among young children(Reference Johnson, Ramsay and Shultz89). HS teachers may need additional support from staff focused on family engagement to develop strong partnerships with families(Reference Lynch and Batal12,Reference Tucker, van Zandvoort and Burke88) , and training focused on communication skills to ensure messages about diet and PA are communicated to families(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13,Reference Lebron, Ofori and Sardinas21) . Health promotion programmes in HS using teachers should carefully consider these challenges and design evidence-based strategies to improve teacher–parent interaction and relationship building(82,Reference Foster, Contreras and Gold86,Reference Ross, Macia and Documet90) .

Making the connection between personal health experiences and professional health promotion

A unique aspect of this study was the ability to look across teachers’ personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and PA. Interestingly, many teachers clearly made connections between their personal and professional experience with healthy eating and PA at the Human Aggregate. Similar to Lebron et al. (Reference Lebron, Ofori and Sardinas21), teachers described the importance of role modelling healthy behaviours for the children in their classroom after receiving an intervention focused on improving their personal health behaviours. While not explicitly acknowledged by teachers, looking across the data, additional connections can be observed across the Social Climate, Organizational Setting and Physical Setting levels. For example, teachers described several personal barriers (social temptations, weather, time) and supports (people, social media, resources and facilities to support exercise, opportunities to learn) that were helpful towards supporting their ability to make positive dietary and PA choices. Studies have shown parents of preschool children share many of these same barriers and supports(Reference Tucker, van Zandvoort and Burke88,Reference Ling, Robbins and Hines-Martin91) .

Professionally, teachers also described barriers to engaging children in healthy eating and PA such as poor-quality meals, weather and limited facilities/resources for PA. Teachers described poor quality school meals as negatively impacting their ability to eat healthy during the school day. Improvements in school meals may work to improve teachers dietary intake and food insecurity(Reference Swindle, Ward and Bokony14). Engaging teachers in the development of menus may help them feel supported by administration in their efforts to make positive dietary choices, while also supporting their ability to create positive mealtime environments and role model eating healthy foods. As previously mentioned, studies have also reported that early childhood teachers may spend a large portion of the day engaging in sedentary activities(Reference Shen, Mao and Liu17,Reference Thorp, Owen and Neuhaus18) . Teachers may not take advantage of opportunities to engage in PA when they arise. Instead of engaging in PA along with children when playing outside, Sisson et al. reported teachers instead viewed this time as an opportunity to take a break or socialise with other teachers. Researchers theorised this was a potential barrier for role modelling(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13). These factors demonstrate that environmental factors in the childcare setting may influence teachers’ behaviours. It may be useful to provide teachers with training on how to advocate for healthy meal options and how to engage children in PA (indoors and outdoors) throughout the day while also helping the teacher to eat healthy and remain physically activity.

Limitations and strengths

The current study had limitations and strengths that should be acknowledged. Considering the qualitative nature and limited geographic scope of the study, findings may not be generalised to other HS teachers. Teachers in this study were 100 % female and primarily African American, demonstrating limited gender and ethnic diversity among the perspectives expressed. Additionally, recruitment was limited to teachers who had recently completed the FESMM intervention. The views of these individuals may be different from other HS teachers, even within eastern NC. With this being said, demographics are similar to those reported by other studies of HS teachers employed in NC(Reference Carraway-Stage, Henson and Dipper35,62,Reference Stage, Wilkerson and Hegde92) . Future research should explore individual, social and environmental influences of teachers’ health behaviours in more diverse populations (e.g. gender, ethnicity, type of early child and education care setting) and geographic locations. Semi-structured interviews following completion of the FESMM completion could be subject to social desirability bias. Some of the topics discussed in the interviews were sensitive in nature and may have resulted in skewed participant responses regarding their personal and professional experiences. Additionally, participants may have felt socially obligated to provide positive responses after being provided the opportunity to engage in FESMM. To reduce the likelihood of this outcome, none of the individuals who delivered the FESSM interventions were involved with data collection. To decrease the likelihood of this limitation, interviewers were trained to minimise this type of bias by remaining open to teachers’ perspectives by remaining unbiased and nonjudgmental(Reference Hall, Chai and Albrecht46). It is important to recognise that the interviews in the current study were conducted prior to implementation of CACFP changes in 2017. It is possible teacher perceptions related to school meals have changed as result of these improvements and the passage of time. Finally, the primary theme of ‘Making the Connection’ was emergent from the data. As an unexpected phenomenon, limited questions were asked in the interview guide that promoted teachers to directly reflect on their perceptions of interrelationships they see between their personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and PA. Future research should explore the interrelationship between teachers’ personal health behaviours and their health promotion practices in the classroom. The study also had many strengths. Researchers used a rigorous approach in the data collection and analysis, including stakeholder engagement to inform the study protocols, pilot testing the interview guide, strong methods of trustworthiness, a standardised approach to training interviewers and coders(Reference Hall, Chai and Albrecht46), drawing from a sample of teachers who all experienced the same intervention focused on improving their healthy eating and PA behaviours.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of considering personal and professional determinants of health when working with early childhood teachers. To the author’s knowledge, it is one of the first studies to explore both teachers’ experiences with their personal health and their health promotion practices in the classroom allowing researchers to observe where the two worlds intersect. Understanding how teachers view their personal health behaviours in relation to their role as a teacher to promote healthy behaviours may help researchers identify opportunities for strengthening interventions to promote teacher health and consequently children’s healthful behaviours(Reference Song, Song and Nieves16).

Teachers want to improve health behaviours personally and professionally; however, well-described barriers exist at all levels influencing their ability to improve their own health and facilitate positive behaviours among the children/families they serve. Findings from the current study and others suggest that the early childhood setting itself may make it difficult for teachers to improve their personal health behaviours (e.g. poor quality meals, limited PA throughout the day), which may later impact teachers’ professional practice through role modelling and child/parent education efforts. Administrators and teachers should be provided with professional development on how to implement policy and best practices in healthy eating and PA that are also supportive of teachers’ personal health goals, as well as the children and families served. More research is also needed to understand influential contextual factors (e.g. background, prior experiences, personality types, attitudes, values) among teachers who have positive v. negative views about their ability to make an impact on the health behaviours of the children and families they serve.

Many prevention/intervention efforts are founded on the assumption that increasing knowledge and awareness among providers will result in positive behaviour changes in the classroom. However, findings from the current study and others suggest researchers should not assume that providing teachers with healthy eating and PA education is enough to build their efficacy to pass on that knowledge and experience to children and families(Reference Lanigan22,Reference Freedman and Alvarez29,Reference Erinosho, Vaughn and Hales93) . Some teachers may need more support in understanding the connection between their personal and professional experiences, recognising opportunities to advocate for healthy eating and engage in PA throughout the day, and support families in their efforts to make positive health choices. Finally, if we desire teachers to help families make actual behaviour changes, professional development in creating strong teachers–parent partnerships around healthy eating and PA topics may also needed. If a teacher perceives it to be her responsibility to get families to change their behaviours, and fails, this could augment feelings of discouragement and helplessness reported by some teachers in the current study and others (Sisson et al., 2017)(Reference Sisson, Smith and Cheney13,62) .

The success of obesity prevention programmes in the HS setting is dependent on teachers embracing and implementing developed programming into their classrooms(Reference Lumeng, Kaplan-Sanoff and Shuman11). As researchers and interventionists, we should be clear about teachers’ role expectations (e.g. education or helping make behaviour changes) and provide professional development accordingly(Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein19). Teachers with limited nutrition background are unlikely to implement and support effective healthy eating and PA programming in childcare settings without additional support(Reference Dunn, Burgermaster and Adams94). Teaching teachers how to promote healthy eating and PA may help them serve as more positive role models for children and parents and strengthen teachers’ ability to promote healthy behaviours(Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein19); however, more research is needed to fully understand the impact of teachers’ personal health behaviours on the strategies they use to promote health in their classrooms. Understanding the determinants of health that influence their personal and professional experiences with healthy eating and PA and the connections between is a step in that direction.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the HS centers and teachers who participated in the study. Additionally, the authors thank the research staff who supported the data collection process: Faiza Mustafa, Kristina Bandy and Joshua Butler. Permission was requested and granted from all persons acknowledged. Financial support: This work was supported by the East Carolina University Engagement of Scholarship Academy. East Carolina University Engagement of Scholarship Academy had no role in the design analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: V.C.S. conceived the study, took lead in its design, conduct, coordination and data collection. L.S.G. and L.J. supported the study design by reviewing protocols and the interview guide. V.C.S. and J.B. led the qualitative analyses. V.C.S. led the alignment of themes and subthemes with the Theory of Social Ecology with support and feedback from J.B., L.S.G., D.D. and V.C.S. led the writing of the manuscript while D.D., L.J., A.H., J.B. and L.S.G. contributed editing of the entire paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the East Carolina University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.