Depression and anxiety in children and adolescents have been a frequent focus of research in clinical and psychological studies over the last decade(Reference Pine, Cohen and Gurley1,Reference Kessler and Walters2) . Adolescence as a group of exceptional age, more than any other developmental period, entails experimentation, exploration and risk taking. The adolescent’s physiology and psychology are in a period of maturity and transition(Reference Cillessen and Borch3). Adolescents are often vulnerable to external influences, causing a variety of psychological problems(Reference Oyserman, Bybee and Mowbray4). Specifically, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in adolescents is relatively high(Reference Rice, Harold and Thapar5). Owing to the pressure of the entrance examinations and the domestic one-child structure in China, the incidence of depression and anxiety in adolescents is creeping up(Reference Shen, Hu and Sun6).

Depression and anxiety that occur during the teen years are considered an important public health problem because of the heavy disease burden for the family(Reference Wittchen and Jacobi7). Anxiety and depression are also linked to medical morbidity and mortality(Reference Azzopardi, Sawyer and Carlin8). Although suicide is uncommon in adolescents compared with non-fatal self-harm(Reference Giannetta, Betancourt and Brodsky9), the prevention of suicide in young people is a focus of national strategies for suicide prevention(Reference Taylor, Kingdom and Jenkins10). If the symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents are underappreciated or neglected, the adverse effects may continue into the adult stage(Reference Najman, Hayatbakhsh and Clavarino11).

The consumption of soft drinks is widespread globally(Reference Jebb12). In the USA, the annual consumption of carbonated soft drinks per capita has risen from 47·5 litres (12·5 gallons) in the 1950s to 212 litres (56 gallons) in 2000, and adolescents are the main consumers(Reference Bere, Glomnes and te Velde13). Soft drinks primarily include soda water, syrup, or other carbonated or non-carbonated beverages, and they contain substantial amounts of added sugars(Reference Vartanian, Schwartz and Brownell14). ‘Syrup’ refers to high-fructose corn syrup, which has been increasingly used in soft drinks in the Asian market(15). Added sugars include syrups and other caloric sweeteners such as fructose, glucose, brown sugar, etc., but do not include naturally occurring sugars such as those in fruit or milk(16). Soft drink consumption in developed countries accounted for 7 % of total energy intake in the diet during 2010 to 2012(Reference Malisova, Bountziouka and Zampelas17).

Given the popularity of soft drinks, a growing number of studies have examined the relationship between their use and various health outcomes. Research has shown a correlation between soft drink consumption and diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes(Reference Apovian18). In recent years, the effects of soft drinks on mental health have also attracted research interest. Preliminary evidence suggests a possible link between sugar intake and depression(Reference Westover and Marangell19–Reference Knüppel, Shipley and Llewellyn21). Although studies from Europe and the USA show a consistent link between soft drink consumption and mental health problems among adolescents as well as older adults(Reference Lien, Lien and Heyerdahl22,Reference Guo, Park and Freedman23) , data from the Asian population are rare. In recent years, one study reported that higher levels of soft drink consumption in Chinese adults are associated with increased symptoms of depression(Reference Yu, He and Zhang24).

We conducted a cross-sectional study among a group of first-year college students to investigate the association between soft drink consumption and symptoms of depression or anxiety in Chinese adolescents.

Methods

Study design

A comprehensive university in Changsha, China, with geographically dispersed enrolment policy, was chosen as the sampling unit. All newly enrolled students who consented to participate underwent a health examination (to measure height and weight) as well as completed an online questionnaire survey (to measure soft drink intake, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and other variables) in September 2017. More details of the study can be found in elsewhere(Reference Xiao, Huang and Jing25). The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number 201709993).

Measurements

A web-based questionnaire survey was conducted to measure outcomes and risk factors including soft drink intake. The survey took place on a single day organized by the Department of Student Affairs of the university. The participant freshmen filled out the questionnaire in separate computer rooms where privacy was guaranteed. During the survey, three investigators were assigned to each room to provide technical support.

The outcome variables of the study were symptoms of anxiety and depression, as measured by the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-2) and the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), respectively. GAD-2 and PHQ-2 are the abridged versions of GAD-7 and PHQ-9. The Chinese versions of the tools have been validated previously(Reference Liu, Yu and Hu26,Reference Yu, Zhou and Liu27) .

Frequency of carbonated soda, sweetened tea drink and fruit-flavoured drink intake per week was inquired using the questionnaire. Daily sugar intake (grams) from soft drinks was calculated as: (frequency of carbonated soda per week/7) × sugar content per-serve + (frequency of sweetened tea drink per week/7) × sugar content per-serve + (frequency of fruit-flavoured drink per week/7) × sugar content per-serve. The sugar content in each type of soft drink was described in a previous paper(Reference Huang, Zhang and Li28). Daily sugar intake from soft drinks was further categorized by quartiles (0, 15 and 25 g/d).

The questionnaire was comprised of eighty-four questions, including demographic information (ethnicity, original region, household annual income in yuan), disease history, behavioural characteristics (cigarette smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, soft drink intake, water intake, exercise, etc.). Height and weight were measured by nurses using standardized methods. BMI was calculated as [weight (kg)]/[height (m)]2.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the participants were presented across the groups of soft drink intake frequency. Continuous data were presented as mean and sd, and between-group differences were tested using ANOVA. Categorical data were presented as number and percentage, and between-group differences were tested using the χ 2 test.

Two-level linear models (student as level 1 and province as level 2) were used to estimate the effects of frequency of soft drink intake on anxiety/depression, adjusting for level-1 confounders (age, gender, ethnicity, annual household income, daily water intake, alcohol drinking, passive smoking, frequency of sport, time of sedentary activities per day, BMI) and level-2 confounders (geographic region). Unadjusted and adjusted means of GAD-2 and PHQ-2 scores by groups of soft drink (sugar) intake frequency, and 95 % CI, were estimated from the model and plotted. Mean differences in multiple comparison were tested by the least significant difference t test. The mediation effects of BMI in the associations of sugar intake with anxiety and depression were also tested using structural equation modelling. P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SAS version 9.2.

Results

In total, 8226 students consented to participate, underwent the health examination and completed the questionnaire. Students with hypertension (n 39), hyperlipidaemia (n 6), diabetes (n 1), hyperuricaemia (n 6), polycystic ovary syndrome (n 22), tuberculosis (n 16), hepatitis B (n 23), hyperthyreosis (n 10), hypothyroidism (n 5), rheumatoid arthritis (n 4) and psoriasis (n 9) were excluded from the analysis, leaving 8085 participants in the final analysis.

Characteristics of the participants stratified by the frequency of soft drink (any kind) intake are shown in Table 1. Of participants, 785 (10 %) had soft drinks seven or more times each week. More frequent intake of soft drinks was associated with higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, higher annual household income, higher frequency of sport, more sedentary activities, more passive smoking and alcohol drinking, and higher frequency of defecation.

Table 1 Participant characteristics by frequency of soft drink intake in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017

* North: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia; Northeast: Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang; East: Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Taiwan; Central: Henan, Hubei, Hunan; South: Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hong Kong, Macao; Southwest: Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet; Northwest: Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang.

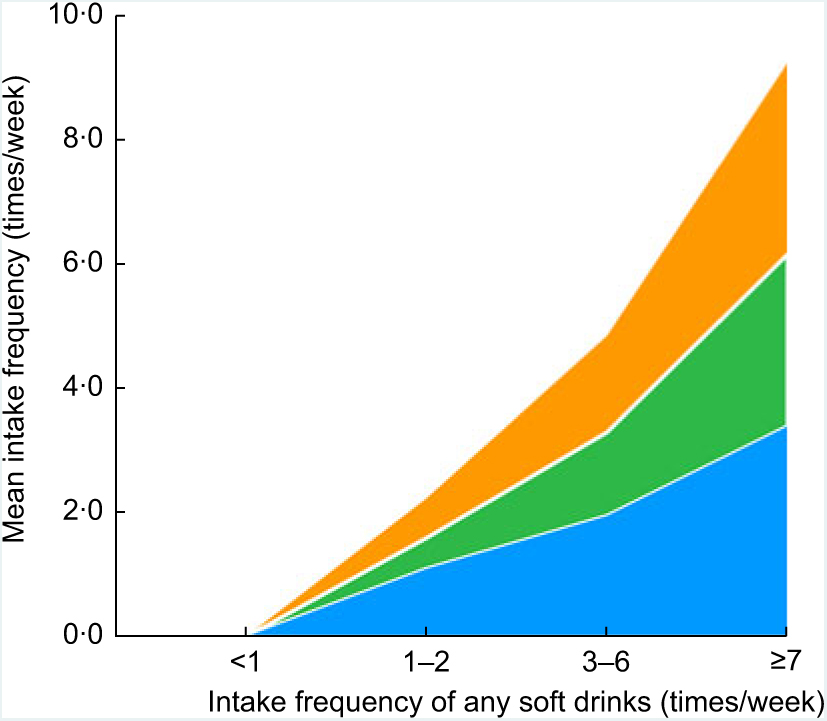

The mean intake frequencies of the three soft drinks across the intake frequency group of any soft drink is shown in Fig. 1. Intake of fruit-flavoured drink accounted for the largest proportion, while the intake frequency of soda was slightly higher than that of sweetened tea drink across the overall intake frequency groups.

Fig. 1 Cumulative area map for the mean intake frequencies of the three soft drinks (![]() , soda;

, soda; ![]() , sweetened tea drink;

, sweetened tea drink; ![]() , fruit-flavoured drink) across the intake frequency groups of any soft drinks in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017

, fruit-flavoured drink) across the intake frequency groups of any soft drinks in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017

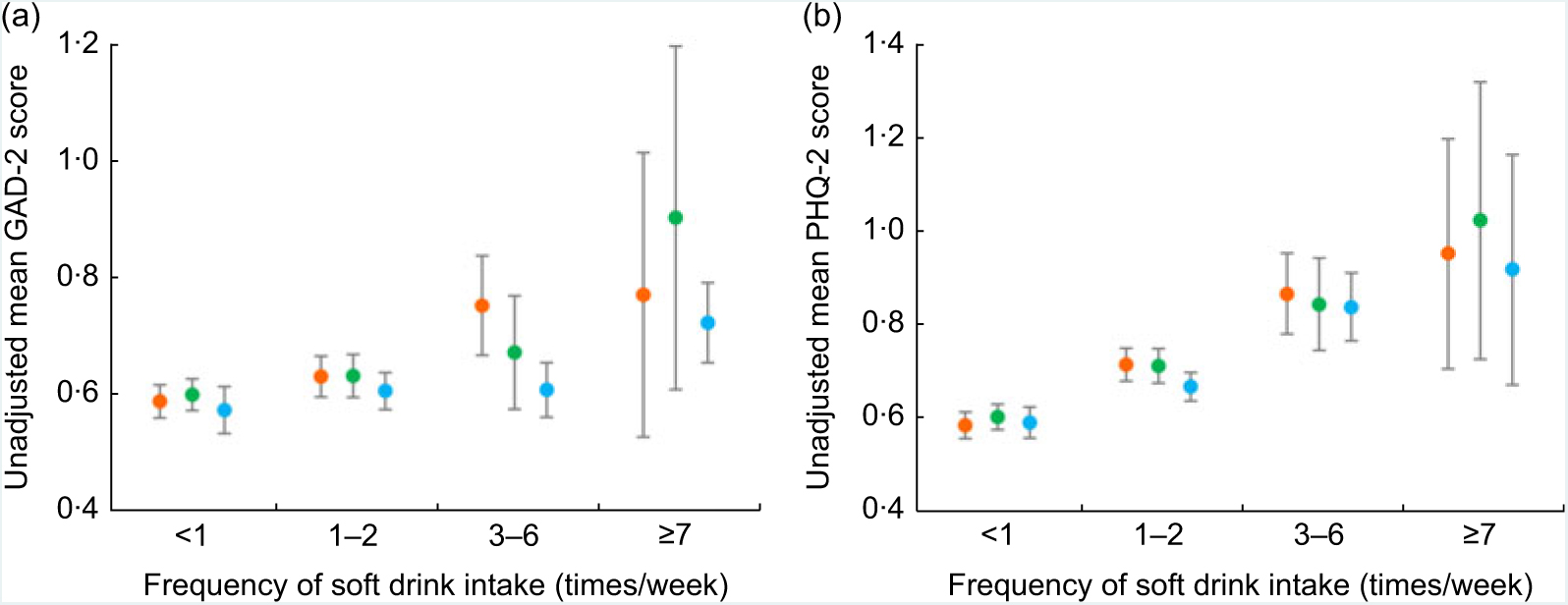

As shown in Fig. 2, GAD-2 and PHQ-2 scores were positively associated with the intake frequency of carbonated soda, sweetened tea drink and fruit-flavoured drink, respectively (all P for trend < 0·01). Multiple comparisons showed larger variations in GAD-2 than PHQ-2. For those consuming soft drinks seven or more times weekly, the CI of the means were wide and overlapped with the CI of less-frequent drinkers. Interestingly, the GAD-2 score among participants consuming soda three to six times weekly (mean = 0·75; 95 % CI 0·67, 0·84) was significantly higher than that among participants consuming fruit-flavoured drink with the same frequency (mean = 0·61; 95 % CI 0·56, 0·65). In contrast, there was no difference when comparing PHQ-2 by the type of soft drinks.

Fig. 2 Unadjusted mean scores of anxiety (measured using the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2)) and depression (measured using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)), grouped by frequency of specific soft drink intake, in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017. (a) GAD-2 mean scores and specific soft drink intake frequency; (b) PHQ-2 mean scores and specific soft drink intake frequency ( , soda;

, soda;  , sweetened tea drink;

, sweetened tea drink;  , fruit-flavoured drink). Means, with their 95 % CI represented by vertical bars, were estimated from two-level linear models with students as level 1 and province as level 2

, fruit-flavoured drink). Means, with their 95 % CI represented by vertical bars, were estimated from two-level linear models with students as level 1 and province as level 2

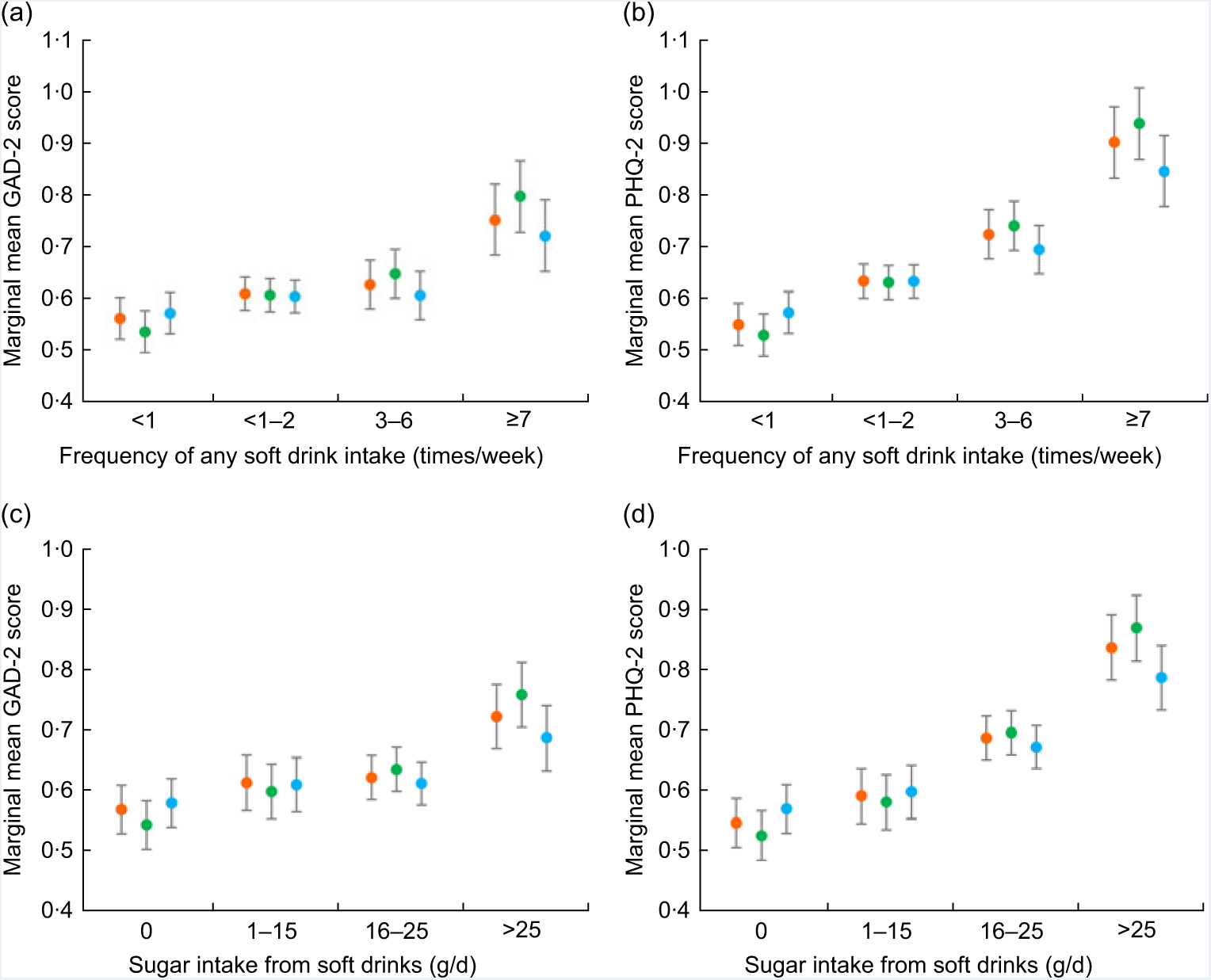

The intake frequency of all soft drinks was then combined for further analysis. As shown in Fig. 3(a) and (b), the frequency of soft drink intake was positively associated with GAD-2 and PHQ-2 scores in a dose–response manner (both P for trend < 0·001). After adjustments for demographic and behavioural factors, the results remained consistent. In multiple comparisons, those consuming soft drinks seven or more times weekly had significantly higher marginal mean scores of GAD-2 (mean difference = 0·15; 95 % CI 0·07, 0·23) and PHQ-2 (mean difference = 0·27; 95 % CI 0·19, 0·35) compared with those barely consuming soft drinks, adjusted for demographic and behavioural factors. Soft drink intake showed larger effect size for PHQ-2 than GAD-2. Analysis with sugar intake quartiles showed consistent results (Fig. 3(c) and (d)): those consuming >25 g of sugar from soft drinks daily had significantly higher GAD-2 (mean difference = 0·11; 95 % CI 0·04, 0·18) and higher PHQ-2 (mean difference = 0·22; 95 % CI 0·0·15, 0·29) scores compared with non-consumers.

Fig. 3 Unadjusted and adjusted mean scores of anxiety (measured using the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2)) and depression (measured using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)), grouped by frequency of any soft drink intake or quartile of sugar intake from soft drinks, in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017. (a) GAD-2 mean scores and frequency of any soft drink intake; (b) PHQ-2 mean scores and frequency of any soft drink intake; (c) GAD-2 mean scores and quartile of daily sugar intake from any soft drinks; (d) PHQ-2 mean sores and quartile of daily sugar intake from any soft drinks ( , means estimated from unadjusted model;

, means estimated from unadjusted model;  , means estimated from model adjusted for demographic factors;

, means estimated from model adjusted for demographic factors;  , means estimated from model adjusted for demographic and behavioural factors). Means, with their 95 % CI represented by vertical bars, were estimated from two-level linear models with students as level 1 and province as level 2. Demographic factors include age, gender, ethnicity and annual household income. Behavioural factors included daily water intake, alcohol drinking, passive smoking, sport, sedentary activities, defecation and BMI

, means estimated from model adjusted for demographic and behavioural factors). Means, with their 95 % CI represented by vertical bars, were estimated from two-level linear models with students as level 1 and province as level 2. Demographic factors include age, gender, ethnicity and annual household income. Behavioural factors included daily water intake, alcohol drinking, passive smoking, sport, sedentary activities, defecation and BMI

In addition to soft drink intake, higher GAD-2 and PHQ-2 were also found to be significantly associated with less sport participation, longer sedentary activities, alcohol drinking, passive smoking, less water intake (except drinks) and irregular defecation habit, according to the two-level multiple linear models (data not shown).

Because soft drink intake was also associated with higher BMI, we tested the mediation effects of BMI in the associations of sugar intake with anxiety and depression. According to Fig. 4, BMI showed a significant but small (7·4 %) mediation effect on GAD-2. By contrast, BMI had no mediation effect on PHQ-2; sugar intake independently increased the level of depression. The mediation analysis was further performed by the type of soft drinks (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1). BMI mediated 0–4 % of the effect of a certain soft drink on GAD-2 or PHQ-2. The effect size was negligible despite statistical significance.

Fig. 4 Mediation effects of BMI on the associations of daily sugar intake from any soft drinks with anxiety (measured using the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2)) and depression (measured using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)) in the sample of students (n 8085) newly enrolled in a comprehensive university in Changsha, China, 2017. (a) Total effects of sugar intake; (b) direct effects of sugar intake and mediation effects of BMI

Discussion

Our study revealed a dose–response relationship between soft drink intake and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents. Those consuming soft drinks ≥7 times/week, or consuming >25 g sugar/d from soft drinks, had significantly higher GAD-2 and PHQ-2 scores, compared with those barely consuming soft drinks. BMI slightly mediated the association of sugar intake with GAD-2, but the effect size was clinically negligible. Soft drink intake brought an independent risk for symptoms of anxiety and depression after adjustments for demographic characteristics, obesity and behavioural risk factors.

Soft drinks contain large amounts of sugar, which has been found to be associated with a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety(Reference Shi, Taylor and Wittert29). Several possible mechanisms linking sugar consumption and anxiety/depression are assumed, including oxidative stress response(Reference Maes, Kubera and Obuchowiczwa30) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT or serotonin) mechanism(Reference Fakhoury31). A high-glycaemic-load diet is associated with higher level of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation associated with oxidative stress. Increased inflammation and circulating cytokines have been linked to anxiety and depression in a wide range of studies. Therefore, a possible biological explanation for the link between soft drinks and anxiety/depression is related to the endothelial dysfunction or a higher level of inflammation.

In mechanistic studies with murine models, researchers showed that long-term diet rich in sugar is associated with decreased effectiveness of somatodendritic serotonin-1A receptors, which provide feedback control over the synthesis and release of serotonin (mood regulator) in the hypothalamus(Reference Inam, Jabeen and Haleem32). Hypothalamus serotonin plays an essential role in the occurrence of mental illness. The decrease of serotonin in man increases the possibility and vulnerability of anxiety and depression(Reference Lindseth, Helland and Caspers33). Tryptophan is the sole precursor of peripherally and centrally produced serotonin. It was reported that fructose malabsorption is associated with lower tryptophan levels that may play a role in the development of depressive disorders(Reference Ledochowski, Widner and Murr34). In fructose malabsorbers, fructose remains unabsorbed in the intestine after consumption of foods or sweeteners with high ratio of fructose to glucose, as occurs in high-fructose corn syrup, apples or apple juice, pears, watermelons and mangoes. Researchers hypothesized that the unpaired excess free fructose that remains in the intestine of fructose malabsorbers reacts with l-tryptophan (via the Maillard reaction). This interferes with l-tryptophan’s absorption, availability and metabolism, which in turn reduces the biosynthesis of serotonin.

Later, a series of studies examined the associations of excess free fructose with chronic diseases. Differential associations between soft drinks and asthma were observed among drinks with similar sugar content yet different proportions of free fructose in epidemiological studies(Reference DeChristopher, Uribarri and Tucker35,Reference DeChristopher, Uribarri and Tucker36) . DeChristopher proposed the hypothesis that fructose malabsorption or intake of foods with high fructose-to-glucose ratio may contribute to gut formation of immunogens that promote chronic respiratory conditions(Reference DeChristopher37). Another potential mechanism involving gut microbiota was summarized by Marsland et al. in a review(Reference Marsland, Trompette and Gollwitzer38). Epidemiological studies also addressed the association of excess free fructose with asthma(Reference DeChristopher39,Reference DeChristopher and Tucker40) . This is consistent with our finding that participants consuming soda 3–6 times/week had higher GAD-2 compared with those consuming fruit-flavoured juice with the same frequency. High-fructose corn syrup has been predominantly used as the added sugar in soda, while fruit drink may have a lower fructose-to-glucose ratio. Unfortunately, we did not inquire specific details on fruit drink (e.g. apple juice v. orange juice), so it was not possible to make this inference.

While there is experimental evidence, human data regarding the association are sparse. To our knowledge, the present study is among the first linking soft drink consumption with mental disorders in Asian adolescents. The results are consistent with those in European adolescents(Reference Lien, Lien and Heyerdahl22). Adolescents are the major group of soft drink consumers; therefore, it is of great significance to investigate the relationship between soft drink consumption and mental symptoms and to suggest preventive strategies. From the perspective of public health, less frequent intake of soft drinks should be considered as a dietary suggestion for adolescents. Young people carry the hope of the family and society, and if symptoms of anxiety and depression arise for a variety of reasons, the effect on the family and society can be burdensome. Severe anxiety and depression may even result in self-injury and suicide among adolescents(Reference Tang, Yu and Wu41).

The present study has limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study and the causality could not be inferred from the observed associations. Second, the representativeness of the sample might be limited owing to the selection bias in monocentric research. We will expand the sampling units in the near future. Third, we did not perform food frequency investigation and total sugar/energy intake from foods was unknown. Finally, face-to-face diagnosis of anxiety and depression was not performed because of limited feasibility. However, GAD-2 and PHQ-2 had good sensitivity and specificity according to previous research. Beside the limitations, the study had a large sample size, an extremely high response rate and completeness of questionnaires, because the survey was organized by the Department of Student Affairs.

In summary, there is a dose–response relationship between soft drink intake and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents. Those consuming soft drinks seven or more times weekly, or consuming more than 25 g of sugar daily from soft drinks, are likely to have higher levels of anxiety and depression compared with non-consumers. Obesity is not likely to mediate the associations. Less frequent intake of soft drinks is suggested to prevent anxiety and depression in adolescents.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would thank the following investigators who participated in the field survey (in order of family name): Lei Cai, Duling Cao, Qin Cao, Chao Chen, Menglin Chen, Jia Guo, Yeye Guo, Rui Hu, Xing Hu, Kai Huang, Xinwei Kuang, Li Lei, Jie Li, Keke Li, Yayun Li, Dihui Liu, Nian Liu, Panpan Liu, Runqiu Liu, Zhongling Luo, Manyun Mao, Qunshi Qin, Lirong Tan, Ling Tang, Ni Tang, Tianhao Wu, Yun Xie, Siyu Yan, Lin Ye, Yi Yu, Hu Yuan, Rui Zhai, Mi Zhang, Jianghua Zhang, Jianglin Zhang, Zhibao Zhang, Shuang Zhao, Yaqian Zhao and Youyou Zhou. Financial support: This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (grant numbers 2015FY111100 and 2016YFC0900802) and the Department of Science and Technology of Hunan Province (grant number 2018SK2086). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declared no conflict of interest. Authorship: X.Z., X.H., Y.X., Y.H., D.J., L.C. and M.S. participated in the field survey and data collection. X.Z. drafted the manuscript. M.S. analysed the data. X.Z., X.H. Y.X., and M.S. designed the questionnaire. D.L., X.C. and M.S. designed the study, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. X.C. obtained the funding. All authors gave final approval to the version submitted for publication. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the institutional research ethics boards of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number 201709993). Written informed consent was obtained from all students before the investigation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001009

Author ORCID

Minxue Shen, 0000-0003-0441-9303.