Sociodemographic characteristics(Reference Drewnowski1) and place of residence(Reference Befort, Nazir and Perri2) have a profound impact on diet quality, food security and the prevalence of diet-related diseases. Individuals living in rural areas are at greater risk for obesity(Reference Befort, Nazir and Perri2), as are non-white populations(Reference Caprio, Daniels and Drewnowski3). While data are limited, Native American communities experience staggering health disparities(Reference Sarche and Spicer4), and the present study focused on the Navajo Nation. Located in the Southwest USA, the Navajo Nation is the largest Native American tribe by land-base with 174 000 residents living in 110 chapters (or towns)(5). Over half of Navajo residents live below the poverty line, 42 % are unemployed and one-third live in houses that lack plumbing and electricity(Reference Tarasi, Alexander and Nania6).

According to the US Department of Agriculture, the Navajo Nation is a food desert: the region’s census tracts are low-income where a significant number of residents live over 32·2 km (20 miles) from the nearest supermarket(7). Local studies illustrate a more dire situation, where travelling 72·4–96·6 km (45–60 miles), each way, for groceries is a normal occurrence(Reference Eldridge, Jackson, Rajashekara and Ivers8,9) . Consequently, families shop for groceries only once or twice per month, as was reported by 50 % of nearly 400 individuals interviewed in Eastern Navajo Nation(9). There are thirteen grocery stores across the 69 932 km2 (27 000 mile2) Navajo Nation territory. Families living far from grocery stores have small stores in closer proximity. However, healthy food options at smaller stores are limited and those that are available are often of lower quality and more expensive than those at larger stores(Reference Larson, Story and Nelson10,Reference Kumar, Jim-Martin and Piltch11) . This is particularly concerning in the Navajo Nation where residents experience some of the highest levels of both food insecurity and diet-related chronic diseases in America(Reference Eldridge, Jackson, Rajashekara and Ivers8,Reference Gittelsohn, Kim and He12) . Access to healthy foods in the Navajo Nation is a social and environmental justice issue that has been exacerbated by forced relocation of the Navajo people, colonialism and loss of culture and traditions(Reference Eldridge, Jackson, Rajashekara and Ivers8). Farming had been an integral part of life on the Navajo Nation; however, the above conditions, changing priorities and unfavourable agroecological circumstances have contributed to a marked decline in production(Reference Setala, Bleich and Speakman13). Despite these challenges, there has been a rise in financial and technical assistance aiming to bolster local farming practices that include increasing market access(Reference Demarco14,Reference Moorman15) .

While consuming a healthy diet is influenced by many factors both internal and external to the individual, a health-promoting food environment is one necessary component. However, little is known about the retail challenges and possible facilitators to supplying healthy foods to the most remote regions in the Navajo Nation. Public health initiatives focused on increasing the healthfulness of small store offerings are widely implemented(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn16), including efforts in rural(Reference Pitts, Bringolf and Lloyd17) or Aboriginal(Reference Lee18–Reference Brimblecombe, Ferguson and Chatfield20) communities involving store owners or managers. A study looking at the effects of store manager practices on the diets of local communities in two remote Aboriginal areas of Australia found that store managers had significant power over the food supply(Reference Lee18). The study identified that dedication of store management to community wellness was a critical component to offering healthy foods(Reference Lee18). Additionally, it was found that healthier foods were offered in stores where managers exercised advocacy skills to ensure that high-quality fruits and vegetables (F&V) were delivered and stored properly(Reference Lee18).

The current study expands understanding of the challenges to offering F&V by documenting the perspectives of owners and managers of small stores in the New Mexico region of Navajo Nation. The study was focused in one geographic area of the Navajo Nation due to logistical and resource limitations. The results will inform local programmatic and advocacy efforts. Additionally, findings will add to the limited literature base regarding the challenges of offering fresh F&V in remote and tribal communities. Thus, the primary objective of the present study was to investigate the barriers and facilitators retailers face in offering F&V at small stores in remote Navajo Nation.

Methods

Sampling frame and selection of stores

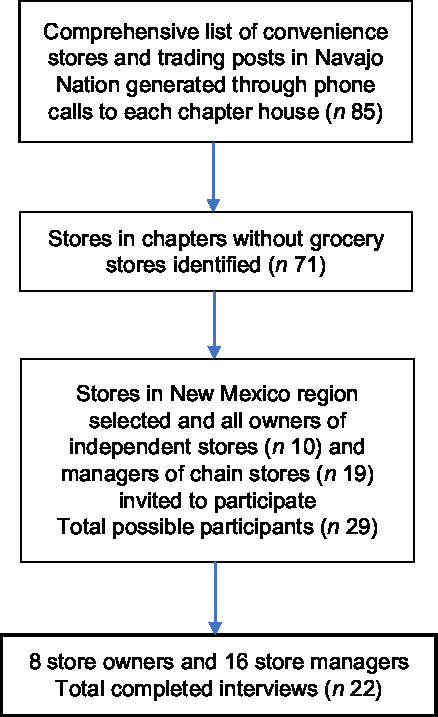

Structured interviews were conducted with store owners and managers of small retail outlets in chapters without grocery stores in the New Mexico region of the Navajo Nation. In collaboration with Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment (COPE), a non-profit organization focused on increasing access to healthy foods in the Navajo Nation, a list of all small stores across the Navajo Nation was compiled by calling each of the 110 chapter houses (or administrative offices). This local knowledge was combined with a list generated through Kumar et al.’s (2016)(Reference Kumar, Jim-Martin and Piltch11) study that utilized an InfoUSA 2011 data set, the Yellow Pages, Google Maps and Navajo Division of Health staff input. In total, eighty-five small stores on the Navajo Nation were identified, seventy-one of which were in chapters without grocery stores, and twenty-nine were in the New Mexico region of the Navajo Nation (Fig. 1). Phone calls were made to store owners (of independently owned stores) and store managers (of regional or national chain stores) to introduce the project and, when there was agreement to participate, schedule a time for an in-person interview. A recruitment script was used to guide the calls. One store was excluded as it was participating in an existing healthy stores initiative and four store owners or managers declined.

Fig. 1 Sampling of store owner and manager interview participants

Survey development and measures

A structured interview guide was developed based on existing studies(Reference Andreyeva, Middleton and Long21,Reference Carty, Post and Ray22) . The authors used a structured, rather than semi-structured, process because the intent of these interviews was to capture a baseline understanding of specific dimensions relevant to offering certain items. Input from COPE staff and partners was incorporated to ensure that information gleaned would be useful for programmatic and policy work. A brief description of the survey sections is provided below and Table 1 is a summary of the dimensions. Most questions asked for brief responses and participants often provided additional context or explanation. The interview guide was pilot tested with store owners in the Arizona region of the Navajo Nation prior to the document being finalized.

Table 1 Topics in interviews conducted with owners or managers of convenience stores and trading posts, Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

* Possible response of strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree and strongly agree.

Background and store characteristics

Store owners and managers were asked if they are Navajo, residents of the community in which the store is located and his/her role at the store. They were also asked if the store they own or operate is a trading post, convenience store or another type of store. Trading posts were historical centres of trade between Navajo artists and outside entities; few are still such centres of trade but operate as independent general stores. Convenience stores are commonly known in the setting as small retail outlets that offer limited food options. Other types of stores included independent small grocery stores or trade centres with laundromats or post offices.

Product selection and sales

Store owners and managers were asked about the foods they offer in their stores, who decides the mix of products and how the decisions are made, if applicable. Participants were asked about the most commonly sold food categories; and if fresh and frozen produce is sold, the most commonly sold types.

Perspectives on accepting SNAP and WIC

Participants were also asked about acceptance of two federal food aid programmes that assist low- and no-income Americans with food purchasing: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). The retailers were asked about the benefits and barriers they have experienced in taking SNAP or WIC.

Stocking and supplying healthy foods

If the retailers offered fresh or frozen produce at their stores, they were also asked for the primary reasons they offer those products and if they experience any challenges in supplying produce. Participants were also asked about their suppliers, the names, types of supplier, and if they do not currently source from Navajo farmers, if they would be interested in doing so. We also asked if they know or have relationships with any farmers.

Perspectives on customers and the community

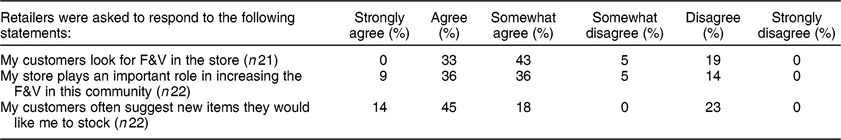

To assess retailers’ perspectives on their customers’ shopping patterns and the role the stores play in the community food environment, questions were asked such as: ‘My customers look for fruits and vegetables (fresh or frozen) in the store’ and ‘My store plays an important role in increasing the fruits and vegetables in this community’. Response options included: ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘somewhat disagree’, ‘somewhat agree’, ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’.

Data collection and analysis

During April–July 2016, twenty-two interviews between 20 and 90 min in duration were conducted (by one author, E.M.P.) at store locations. Interviews began with an introduction of COPE’s Navajo Healthy Stores Initiative: that it assists stores interested in increasing F&V and promoting the products in their stores, and that responses would inform COPE’s projects. The retailers were told that their involvement in the interview was voluntary and that they could skip a question or end the interview at any time. Verbal consent was obtained before the interview commenced and a copy of the consent form was provided. Both the interview guide and verbal consent process were approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. In appreciation of their time, each participant received a basket with fresh F&V (valued at <$US 15). All data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and the statistical software package Stata version 12.1 was used to analyse quantitative data. The survey was developed with the intention of having minimal, to no, open-ended narrative responses. However, some participants chose to provide context for quantitative responses; that information was summarized by question topic. All analyses were conducted by one of the authors (E.M.P.).

Results

Interview participant and store characteristics

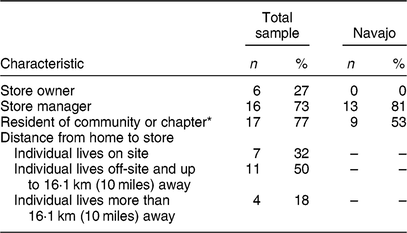

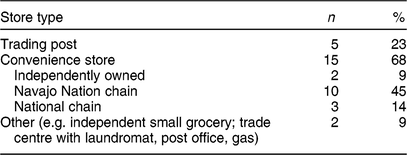

Of the sixteen store managers and six store owners who completed interviews, the mean number of years in his/her respective role was 12·0 (sd 11·6) years, with one manager having just started and one owner having operated his store for 39 years. Almost all store managers reported being Navajo (81 %, n 13) and all store owners were not. Three-quarters of participants reported that they live in the chapter where the store is located (Table 2). Most stores were convenience stores (68·2 %, n 15) with trading posts and other independent stores also represented (Table 3).

Table 2 Characteristics of the store owner or manager interview participants (n 22), Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

* Where store is located.

Table 3 Store types represented in the present study, Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

Product selection and suppliers

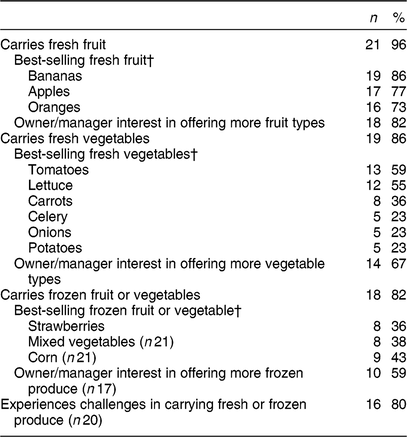

About half (54·5 %, n 12) of participants said he/she is the person who makes the decision about product offerings. Approximately one-quarter (27·3 %, n 6) said that someone else makes the decision and four participants said that it is some combination. The participants who do not make product selection decisions stated that either the chain’s corporate office or the owner of the regional chain was the decision maker. Products were offered based on what customers want and will buy. While many stores source through a food distributor that delivers once or twice per week, some store owners reported being their own suppliers, specifically for fresh F&V. These owners look to supercentres or grocery stores for the best quality and prices to provide to their shoppers. Due to the small volume of perishable items that are sold in the rural areas, some store owners find it most cost-effective to serve as their own suppliers. See Tables 4 and 5 for a complete list of the most commonly sold food types.

Table 4 Best-selling food categories at the small stores (n 22) participating in the present study*, Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

* Store owner/manager provided the three most popular types.

Table 5 Fruits and vegetables sold at the small stores (n 22) participating in the present study*, Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

* All twenty-two participants responded to each question unless n is otherwise noted.

† Store owner/manager provided the three most popular types.

Perspectives on accepting SNAP and WIC

All retailers accepted SNAP benefits and the majority (77·3 %, n 17) took WIC. It was difficult for many store owners or managers to estimate the percentage of their sales that are made with either programme; however, among the values provided, the median percentage was greater for SNAP (40 %; range 5–80 %; interquartile range 20 %) than for WIC (20 %; range 2–30 %; interquartile range 18·8 %).

Retailers reported that accepting SNAP and/or WIC helps both the low-income customer (in terms of providing a convenience close to home) and the store (in that the programmes increase sales). Survey participants stated that WIC aids sales of fresh F&V and other healthy foods. Disadvantages to participating in the programmes included mention of the unhealthy foods that are purchased with SNAP and the ‘SNAP rules’ regulating what can be purchased using the benefits (e.g. not being able to accept SNAP benefits for prepared foods)(23). Of the retailers that took WIC, eleven spoke of challenges, including meeting WIC requirements such as needing to carry certain foods and quantities of items, even if those items never sell. Another challenge was following pricing guidelines, such as only being able to mark-up WIC items a certain amount that would often be less than the stores usually would. Being cognizant of dates was also a theme. One comment was that the store loses out financially when products expire. Another participant stated that the cashiers must be very attentive to expiration dates on the WIC vouchers. Among the stores not taking WIC, the reasons included: the store does not offer groceries; they would participate in WIC if they were asked to; the ‘product requirements are ungodly’; and similarly, not enough people in the community use WIC.

Stocking and supplying healthy foods

Fresh fruit and vegetable offerings and perspectives on stocking additional types

While almost all stores carried some fresh F&V, there were many explanations for why offerings could be limited. Eighty-two per cent (n 18/21) of participants stated that they would like to offer more types of fresh fruits and 73·7 % (n 14/19) would like to offer more fresh vegetables, but the retailers face a variety of impediments to doing so.

A theme that underlies much of the decision-making process about F&V options was that minimal perceived demand drives the level of supply and that fresh options spoil quickly. Store managers face a variety of additional challenges including the fact that they rely on the minimal options available in suppliers’ order books. Additionally, managers indicated that they would offer more options if it was their decision to make. One manager stated that shoppers ask for a variety of fresh items like celery, tomatoes and carrots, but that her own manager says that the store does not serve the role of a grocery store and thus F&V are not appropriate to offer. The store owners interviewed stated that they would provide more options if local residents communicated that there was a need. Four participants shared that the challenges exist in both supply and in the level of perceived sales.

Retailers reported limited motivation to continue offering items or trying new ones after observing poor sales of introduced F&V lines. Two participants stated that WIC recipients are the main purchasers of fruit; single-serving ready-to-eat fresh fruit (prepared on site) were popular at the two stores where they were offered. One store owner in a very remote region stated that fresh F&V spoil quickly, thus he brings it in about two times per week. Another store owner who is also in an extremely remote region and operates an historic trading post shared that he stopped selling fresh fruit 10 years ago. He explained that the older generation would buy healthy foods and F&V at his store but that his current shoppers come in more for soda and snacks.

Still, some store owners were willing to take steps to offer more F&V varieties: one stated ‘whatever people would want to try’; another stated that her own family grows pumpkins and sells them at hay stacks outside the store; and another suggested specific types of F&V that he would be willing to offer that last longer, such as romaine lettuce and chilli peppers. He went on to share that he ‘has a soft spot for unusual produce types like jicama’ and likes to offer different types of produce to introduce his shoppers to new options.

Perspectives on offering frozen fruits and vegetables

The majority of store owners or managers (81·8 %, n 18) stated that they offer at least some frozen F&V. However, six participants stated that frozen F&V do not sell well, and some store managers stated that the selection of items they offer is limited by the few options of their supplier. Other comments made included: not having a freezer or space within the freezer for F&V; that he would supply more frozen F&V if shoppers bought them; and that items like frozen mixed fruit are desirable to offer but too expensive. One store owner shared that she had not tried offering frozen F&V but liked the idea and would consider it in the future. She went on to say that it can be stored longer than fresh and can be healthier than canned. A manager at another store stated that she tries to have the frozen F&V placed next to more popular frozen items, but even this nudge does not influence purchasing patterns.

Reasons for offering fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables

Retailers reported demand for fresh or frozen produce (50·0 %, n 11); that WIC or the Healthy Diné Nation Act (HDNA) requires the items (40·9 %, n 9); that offering them increases healthy purchasing patterns and decreases health issues in the community (36·4 %, n 8); and that the store provides a convenience to shoppers (22·7 %, n 5). Other responses focused on specific populations like the importance of offering healthy options for youth (n 2): ‘because the schools are around, there are kids to provide it to’. Two spoke of more value-driven explanations like ‘it’s the right thing to do’. Two others said that it is determined through the corporation’s main office and not a decision made by the manager interviewed. Of note, while the HDNA was reported as a reason that some retailers offer fresh or frozen F&V, the HDNA did not require produce be sold but imposed a 2 % sales tax on minimal- to no-nutritional-value food items(24).

Challenges with vendors and transportation

There are many limitations and challenges with the vendors utilized by the stores. For example, one participant stated that there are two mark-ups because of how the distribution works. The F&V go through a larger distributor first and then a smaller one and that there are extreme fees to pay for utilizing certain distributors. Some distributors require a minimal amount spent by the store in order for delivery to be feasible. Another stated that 10–15 years ago, he had more options of suppliers that had routes near his store. A manager expressed a similar sentiment: that the corporate office does not have many places from which stores can order. Moreover, managers reported that a new supplier servicing the area had limited offerings but there was optimism that more options might become available as additional stores signed on. One store owner lamented that F&V suppliers are different from suppliers of other products: ‘for milk, bread and potato chip supplies, if they [the distributer] sees expired items on the shelf, they’ll give credit on the next order. If this was done for F&V [by the distributer], that would be amazing.’ Another store owner stated that his distributor has a certain strategy for how fresh F&V are transported on the truck and that this strategy does not seem to work: by the time F&V have got to the store, they have already become bruised. The specific strategy was not provided; however, the message was clear that there are challenges with transportation of certain types of produce to the store.

Perspectives on collaborating with Navajo farmers

Fourteen store owners and managers (63·6 %) said that they were interested in purchasing fresh F&V from Navajo farmers. One participant mentioned that she currently offers F&V brought in by local growers; one was not interested in pursuing such a partnership; and six said that it was not his/her decision to make.

Among the nine trading post owners or primary decision makers who participated in an interview, all but one expressed interest in purchasing F&V from Navajo farmers. One stated that ‘it would be awesome’ and that the local growers would simply need to let management know what they have. For example, this owner mentioned that one employee has chickens and sells their eggs at the store. Community members also bring in pinion nuts and Navajo tea that the store is willing to sell. Another trading post owner said he had no problem buying products from local growers if the items were of good quality and reasonably priced. Another owner mentioned that the growing season is short and could be a limiting factor. He went on to say that he would need to get to know people who grow food in the community for this to occur. Another owner stated that the farmers in the region are primarily Caucasian and not Navajo.

Among the ten study participants who are managers at regional chain stores, half stated that they would like to purchase F&V from Navajo farmers and the other half said that they do not make the decision about where the products are purchased for their stores. Among those who said they were interested, further discussion revealed similar sentiments to the others: that despite their interest, decisions about product sourcing must go through their main office. Managers communicated varying degrees of self-efficacy regarding the steps to take in partnering with local food producers. One manager stated: ‘we’re not allowed to, [the] owner and district manager decide and it’s all about cost, how much he’ll pay and receive, profit.’ Another manager from the same chain said: ‘I would love to, hoping to push for it but not sure how to organize it yet.’ That manager went on to say that there are a couple of growers in the community and that they would have to go through the company headquarters to pursue selling those products. Still another manager was interested in the concept of connecting with Navajo farmers but said that there were not any in the area.

The one participant who expressed disinterest in partnering with Navajo farmers said that his insurance requires US Department of Agriculture approval of the foods he sells. Two owners stated that they would purchase from the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry, with one stating that it was the only local agriculture he knew of. Two of the participants who were willing to sell locally produced products also mentioned the need for agricultural inspections and perceived requirements of certain size and weight labels from the farms. Another said that while it is rare, some local growers offer to sell their F&V and he has considered it. That owner went on to say that ‘they’re mostly ranchers who produce food for their animals. It’s dry farming, very little irrigation. They use the food personally and don’t produce to sell.’

Perspectives on customers and the community

About three-quarters of participants (76·2 %, n 16) agreed, to any extent, that customers look for fresh or frozen F&V in the stores and three-quarters (72·7 %, n 16) agreed, to any extent, that his/her store plays an important role in increasing F&V access in the community. About three-quarters (77·3 %, n 17) of individuals interviewed agreed, to some degree, that their customers suggest new items they would like stocked in the stores (Table 6).

Table 6 Responses to three statements about whether or not customers look for fruits and vegetables (F&V) in the store, if the store plays an important role in increasing F&V in the community and if customers recommend items they would like stocked at the stores, Navajo Nation, New Mexico, USA, April–July 2016

Discussion

The present study reports store owner and manager perspectives on selling F&V in remote Navajo Nation. The retailers interviewed had varied perceptions on F&V demand at their small stores. Most owners and managers felt that their stores play an important role in increasing F&V in the community, that they would like to offer more F&V and that their customers do look for these items in the stores. However, for stores to increase the variety of F&V they offer, demand would need to be higher and suppliers would need to offer more options, two dimensions also identified in rural areas in a review article by Pinard et al. (2016)(Reference Pinard, Byker Shanks and Harden25). Further study detailing the perceived low demand for F&V at small stores on the Navajo Nation juxtaposed with true demand is needed if efforts to increase F&V in remote regions are to be successful. Moreover, the complex determinants relevant to F&V purchasing at small remote Navajo stores merits further study. A large randomized trial in remote Indigenous Australia found that discounting F&V by 20 % saw a population-level increase in purchases(Reference Brimblecombe, Ferguson and Chatfield20); thus fiscal interventions (although resource intensive) could be one strategy for increasing demand in the potential absence of increased supply. Conducting consumer surveys in parallel with retailer surveys would help inform this interplay.

Another important theme identified in the present study was the willingness of retailers to respond to shoppers’ requests. There may be need for assistance in facilitating opportunities for store personnel and shoppers to meaningfully collaborate on increasing supply and purchasing of F&V at the small stores. This topic has been highlighted in corner store initiatives throughout the country and summarized by Gittelsohn et al. (2014)(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn16). Lessons learned from healthy store initiatives nationally acknowledge the potentially complex relationships that exist among retailers and their customers. It was found that ‘relationship quality was moderated by whether there was a shared language and heritage’ (p. 310)(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn16). The store owner participants in our study were Caucasian, with manager participants, and the shoppers they service, primarily Navajo. Successful healthy corner store initiatives that could be modelled have engaged youth in advocacy efforts(Reference Pinard, Byker Shanks and Harden25) and have partnered with local community residents on culturally appropriate marketing campaigns, linking store initiatives with other community revitalization efforts(Reference Ortega, Albert and Sharif26). Providing locally meaningful ways for shoppers and retailers to collaborate could increase the likelihood that shoppers request new items, store owners provide those items and that shoppers close the loop by making the purchases.

While study participants expressed willingness to augment offerings, challenges with food suppliers and distributors persist. There are few food suppliers that carry F&V and have routes to these remote areas. As the present study took place, one of the main food distributors, primarily utilized by regional chain stores, closed; thus the perspectives presented should be interpreted knowing that it was a unique time to be discussing the topic. It is well established that how and from where stores source their F&V directly impact the price and quality of the items(Reference Hadwin27). If small stores in the Navajo Nation are interested in exploring new strategies for sourcing F&V, they could consider recommendations identified through key informant interviews with experts in the small store and food distribution spaces(Reference Hadwin27). One recommendation that could align well with technical assistance COPE is already providing to stores is to research and share the distributor options that exist, including any minimal ordering size and product availability(Reference Hadwin27). It is also important to consider how best to reduce the financial risk to store owners, especially if they are encouraged to try stocking new items. Another potential strategy is for multiple small stores in the Navajo Nation to purchase F&V collaboratively and request partnering with the nearest grocery store to obtain the wholesale pricing of a larger distributor(Reference Hadwin27).

Whether stores are independently owned, or regional or national chains, each store has unique assets and challenges that would make offering more F&V types difficult. When working with store owners and managers on healthy store initiatives, a critical step is understanding who all the players are and how they engage with one another. For example, owners of trading posts might employ managers who are closely connected to the local community. Similarly, regional or national chain stores commonly have store managers who live in the local chapter and are well acquainted with frequent shoppers. We learned that store managers may view their roles and levels of influence differently, even within the same regional or national chain. Thus, a potentially critical role for academic or non-profit staff who provide technical assistance to stores is as convener and facilitator. For example, with regional chain stores, the technical assistance could focus on collaborating with the owner, understanding the current roles and expectations of the managers, and identifying leadership and advocacy skills that could be built among managers. In advocating for more F&V at national chain stores, it is necessary to identify who, within the corporate management structure, would be receptive to discussions about product augmentation.

Setala et al. (2011) interviewed Navajo farmers in Arizona and identified three primary barriers they had with selling to local small stores. Those included: having a limited harvest, lack of crop transportation and the price that local stores were willing to pay(Reference Setala, Gittelsohn and Speakman28). From the store owner and manager perspectives, our study identified that store owners were not aware that local growers existed in the community. There were also concerns about need for US Department of Agriculture certifications. New Mexico State University is supporting small-scale efforts in food production along a north–south corridor convenient to many small stores that participated in the present study(Reference Moorman15). A next step that COPE could take would be to collaborate with New Mexico State University in providing training to both store personnel and local growers on food safety requirements. It is also possible that additional food producers near small stores on the Navajo Nation could be identified through discussing possible collaborations at chapter meetings. As relationships are built between store owners and food producers, discussions about pricing and transportation logistics could be collaboratively pursued.

A considerable amount of pertinent and actionable information was gleaned through the present study. Moreover, we documented perspectives from an owner or manager at the majority of stores in chapters in New Mexico without grocery stores. Given the time and resource limitations of the study, the intention was to speak with one person in a management role at all stores in the geographic region. Our findings point to a need for interviews of both owners and managers of a given store in order to understand the opportunities and limitations of each position in relation to relevant dynamics. While the majority of stores in the region were represented in the present study, the sample was too small to enable comparing perspectives between store owners and managers.

Additionally, funding limitations did not allow for multiple data coders and reviewers. However, this was a minor issue since the majority of each interview was quantitative and/or questions that required very brief narrative responses. Another limitation was that participants knew that they were helping to inform future work increasing healthy food access in the Navajo Nation. Thus, it is possible that responses were influenced towards supporting the work. Still, participants provided candid responses about the challenges they face with supply, perishability and the lack of demand. The present study is the first of its kind documenting perspectives from such a large proportion of possible retailers in the region and can be the basis for further study on supply-chain dynamics and investigating the supply and demand balance in remote Navajo Nation.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the store owners and managers who participated in interviews for this study as well as COPE staff who contributed to this work, including: Carmen George, MS, Memarie Tsosie and Taylor Wilmot. Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agriculture and Food Research Initiative – Food, Agriculture, Natural Resources and Human Sciences Education and Literacy Initiative (AFRI ELI) (E.M.P., award number 2016-67011-24675, 2016) and cooperative agreement number 6 NU58DP005874-03, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (S.S.S.). The USDA NIFA AFRI ELI had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Similarly, the manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: E.M.P., S.S.S., R.F.H. and T.G. all contributed to the design of this study. E.M.P. conducted the interviews, entered and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided comments on multiple drafts and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board and the Tufts University Institutional Review Board. Verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Verbal consent was witnessed and noted.