Globally, Africa is among the regions with the highest rate of urban population increase; about 60 % of the population is projected to live in urban areas by 2050(1). Kenya and Ghana exemplify these trends. By 2020, about a third (28 %) and slightly more than half (57 %) of the Kenya and Ghana’s population respectively was urban(2). Rapid and unplanned urbanisation in low- and middle-income countries is associated with urban poverty and various emerging environmental and health hazards(3). It is also linked to changes in social economic and physical food environments and a subsequent nutrition transition(Reference Hawkes, Harris and Gillespie4) characterised by shifts in people’s food habits such as an increase in the consumption of unhealthy foods that are high in calories, fat, salt and sugar(Reference Hawkes, Harris and Gillespie4). Unhealthy diets are estimated to make a greater contribution to the non-communicable disease burden than alcohol, smoking and physical inactivity, combined(Reference Malhotra, Noakes and Phinney5).

Both Kenya and Ghana are experiencing a nutrition transition, and an increasing trend in overweight and obesity(6). Between 2000 and 2016, the prevalence of overweight and obesity combined increased, from 28 % to 45 % and 12 % to 20 % among women and men respectively in Kenya(7). In Ghana, overweight and obesity combined increased, from 38 % to 58 % and 16 % to 27 % among women and men respectively in the same period(8). Studies from these countries indicate a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in women and urban residents(Reference Agyemang, Boatemaa and Frempong9). Further evidence indicates a higher rate of increase in overweight and obesity among the poorest population segments in urban Africa(Reference Ziraba, Fotso and Ochako10). A systematic review of dietary behaviours in both countries also revealed relatively low consumption of healthy foods, such as fruit and vegetables (52 %) and widespread consumption of unhealthy foods such as sugar sweetened beverages (40 %)(Reference Rousham, Pradeilles and Akparibo11).

The social food environment, defined as the food-related interactions between friends, family and peers,(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien12) has a major influence on individuals’ intent and actual food behaviour(Reference Carbonneau, Lamarche and Robitaille13). The social food environment, including social norms, networks and contexts that promote the adoption of unhealthy dietary behaviour, is a potential underlying factor for the development of obesity(Reference Higgs and Thomas14). Understanding the role of the social food environment in influencing dietary behaviour is important to identify effective interventions for the promotion of healthier diets and prevention of diet-related non-communicable diseases, especially in urban contexts(Reference Holdsworth and Landais15). Currently, there is demand for nutrition policies and interventions to be more evidence-based, context and culturally specific, with recommendations for qualitative research to enhance the understanding of social processes that drive dietary behaviours in urban Africa’s social environment(Reference Holdsworth and Landais15). However, the specific social influences of dietary behaviours in urban contexts are not well documented in Africa(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Mohindra and Booth16), despite the increasing urbanisation and growing trends in overweight/obesity.

Hence, this study aimed to explore the perspectives of communities living in urban cities in Kenya and Ghana on the factors in the social food environment that influence their dietary behaviours. The ‘Photovoice’ methodology that uses the support of photography taken by local people to talk about their environment was used to provide the evidence for this aim(Reference Wang and Burris17). Photovoice allows for an emic approach in investigating how local people identify their own food environment and how they perceive it. It also allows the researcher to see issues ‘through the eyes’ of study participants and communities. This methodology has been used in other high- and low-income countries to understand social food environments as perceived by adults(Reference Nowell, Berkowitz and Deacon18), as well as adolescents and youth(Reference Trübswasser, Baye and Holdsworth19).

Methods

Study setting

This study was part of a wider project(Reference Holdsworth, Pradeilles and Tandoh20) conducted in three rapidly growing urban African cities; Accra and Ho (Ghana) and Nairobi (Kenya). The study in Ho was part of a larger project (drivers of food choices) that targeted women of reproductive age only, whereas the studies in Accra and Nairobi were part of the TACLED project, which included both men and women aged 13 to 49 years(Reference Holdsworth, Pradeilles and Tandoh20). The different cities represented different contexts in East and West Africa, and different levels of urbanisation and nutrition transition, including major cities (Accra and Nairobi) and a secondary city (Ho).

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study that employed Photovoice methodology. Photovoice is a community-based participatory and visual research methodology in which participants are given a camera to capture conditions and issues in their environment, through photographs(Reference Mitchell21). The photographs taken then act as a visual prompt for participants, providing them with an opportunity to describe realities, communicate perspectives and raise awareness of complex public health issues in their environments(Reference Wang and Burris17,Reference Nykiforuk, Vallianatos and Nieuwendyk22) .

Sampling and data collection

As this study focused on lower income groups, a list of all deprived neighbourhoods in the selected cities (excluding slums) was compiled. This list was further restricted by retaining neighbourhoods that were deemed to be safe to work in by the research team. One neighbourhood in each city was then randomly selected using a manual lottery method: James Town (Accra), Dome (Ho) and Makadara (Nairobi).

Within the selected neighbourhoods, participants were purposefully recruited using quota sampling based on key characteristics (i.e. age, gender, BMI, socio-economic level, and education level and occupation status) (Supplementary file 1). This was to ensure breadth in the range of views, perspectives and environments that participants were exposed to. The Photovoice study was carried out on a random sub-sample (i.e. a third) of the overall study population of the wider project (target sample: n 64 in Accra, n 32 in Ho and n 48 in Nairobi; total n 144). Recruitment took place through the communities, schools and health services. Additional information on the sampling and recruitment strategy can be found elsewhere(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23).

Data collection

The Photovoice activity was conducted between September 2017 and June 2018. The format of the Photovoice prompt and interview guide used for this study was adapted from the conventional format proposed by Wang (1999), to suit the research context. The main adaptation that was made for this project was to conduct one-to-one interviews instead of the more collective workshop or focus group discussion approach that is normally used in Photovoice. The individual approach was used because our initial community engagement activities suggested that most of the targeted participants in urban areas were busy with work or school, and it would be hard to bring them together at the same time. In addition, the safety of group gatherings was considered a problem since Kenya was experiencing political instability at the time of data collection.

Prior to the start of data collection, the Photovoice open-ended interview guide was piloted (Accra (n 3), Ho (n 3) and Nairobi (n 4) and subsequently amended. The amendments mainly included simplifying the guiding questions (Photovoice prompts) and rephrasing of sentences to suit the local contexts. During the period of taking photographs, participants were visited four times in their homes by trained research assistants on a day that was most convenient to them. In the first visit, participants were taken through (i) the consent process, (ii) the Photovoice methodology, (iii) the use of a camera to take different types of photographs and (iv) photo ethics including the no face or identification details’ protocol to ensure anonymity of people or places. Participants were then requested to take five photographs during one week that best represented (i) a place where you eat food and/or beverage from; (ii) something that makes healthy eating difficult for you; (iii) something that makes healthy eating easy for you; (iv) something that influences what you eat in your (local) area; and (v) a person that influences what you eat in your (local) area. Two follow-up visits were made by research assistants during the week, to check on the progress and address any issues arising with the photography activity.

After one week, follow-up in-depth interviews to discuss the photographs were conducted, in which the participants told the ‘stories’ of the five photographs they had selected and provided a short caption to describe their favourite photograph. The in-depth interviews were conducted by research assistants, using the Photovoice open-ended interview guides (Supplementary file 2). The interviews were conducted mainly in local languages (Swahili for Kenya, & Twi, Ga and Ewe for Ghana) or (less often) in English. The prompts and interviews guides used were translated into local languages by accredited translators, and then back translated into English, to ensure that meaning was not lost. Interviews were digitally recorded and lasted between 45 and 60 min.

Data analysis and synthesis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy and coded in NVivo 11 by at least two members of the research team in each study site (MNW/RP/AT/SK/FG/AI). All coders were extensively trained, and double coding of 25 % of the transcripts (n 36) was performed to ensure consistency when applying the codebook. Any discrepancies identified during the double coding process were discussed and resolved. External opinion was also sought from another member of our research team (PG) to discuss any unresolved coding approaches.

The approach taken for the development of the codebook and subsequent thematic analysis was both theory-driven, using a priori themes compiled using existing socio-ecological models of dietary behaviours(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien12,Reference Gissing, Pradeilles and Osei-Kwasi24) and data-driven (grounded), to allow for themes emerging from the data.

The socio-ecological model highlights factors influencing dietary behaviours across four levels: individual (preferences, knowledge, socio-demographic characteristics); social (family, friends, and peers); physical (the home, workplace, schools, restaurants, supermarkets) and macro (food marketing, food production, distribution systems)(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien12). All the interviews were coded for individual level factors, social environment factors, physical food environment factors and macro-level factors. This manuscript reports a synthesis of the themes and subthemes on factors in the social food environment that are perceived to influence dietary behaviours in the three cities (Accra, Ho and Nairobi). The findings on the role of the individual- and physical-level food environments on dietary behaviours have been published elsewhere(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23).

Results

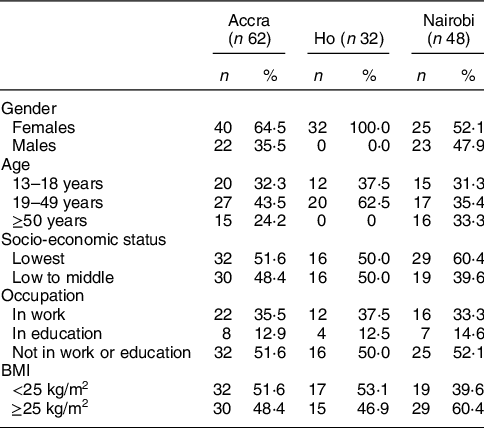

A total of 142 participants from Nairobi (n 48), Accra (n 62) and Ho (n 32) participated in this study, slightly lower than the targeted sample of 144 participants. Overall, 68·3 % of participants were female and nearly half were 19–49 years old. With regard to participants’ occupation, 35·2 % were in work, 13·4 % in education and 51·4 % not in work nor education. The proportion of participants with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was higher in Kenya (60·4 %) than in Ghana (Accra: 48·4 % and Ho: 46·9 %) (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

The themes emerging on the influence of social environment on the participant’s dietary behaviour included (1) family members’ food preferences, (2) family members’ health and nutrition needs, (3) social support by family and friends, (4) provision of nutritional advice and modelling food behaviour by parents and health professionals, and (5) food vendors’ services and social qualities.

Family members’ food preferences

Food preferences for different household members were central to the decisions that participants made on foods purchased, eaten or prepared for the entire household. For instance, in all the three cities, participants acknowledged buying or preparing foods that their children liked or could easily eat or take to school. Among married couples, the food preferences of one spouse influenced their partner’s food choices. Women across all cities reported considering their husbands’ preferences while making decisions on the foods prepared for the family. In Nairobi, some male participants indicated that their food consumption was solely dependent on the foods that their wives cooked for them. Further, some participants from households that had vegetarians or young children reported to mainly cook vegetarian meals or foods that young children could easily eat. Preparing common meals that everyone in the household could eat was seen as convenient, saving time and resources (Table 2).

Table 2 Narratives and photographs on the theme ‘household members’ food preferences’

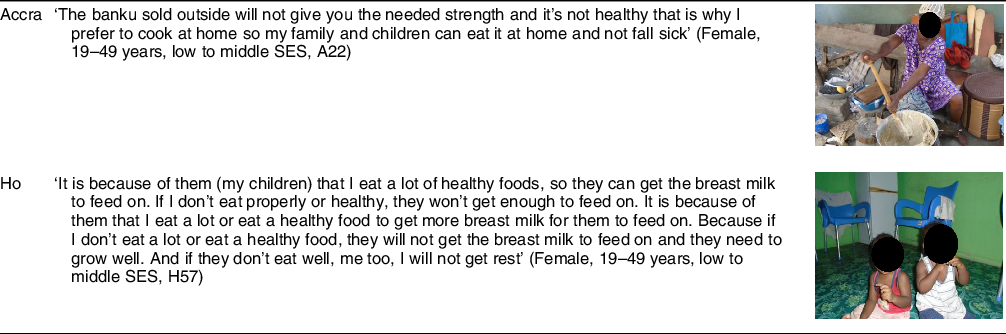

Health and nutritional needs of family members

Considerations for the health and nutrition of various family members influenced the foods purchased, prepared or eaten at home by the rest of the family. In Ghana (Accra and Ho), female participants, mainly in their role as mothers reported preference for foods perceived to promote their children’s health over those that were considered unhealthy. In Accra (but not Ho and Nairobi), there was a preference for preparing meals at home, citing the reasons that home prepared food is healthier, prevents children from falling sick and is cheaper so children can have enough food to satisfy them (Table 3).

Table 3 Narratives and photographs on the theme ‘ health and nutritional needs of the family members’

Social support

Social support, by way of eating together, providing pleasant company during mealtimes and providing support with food provision and preparation emerged as a key influence on participant’s dietary behaviours.

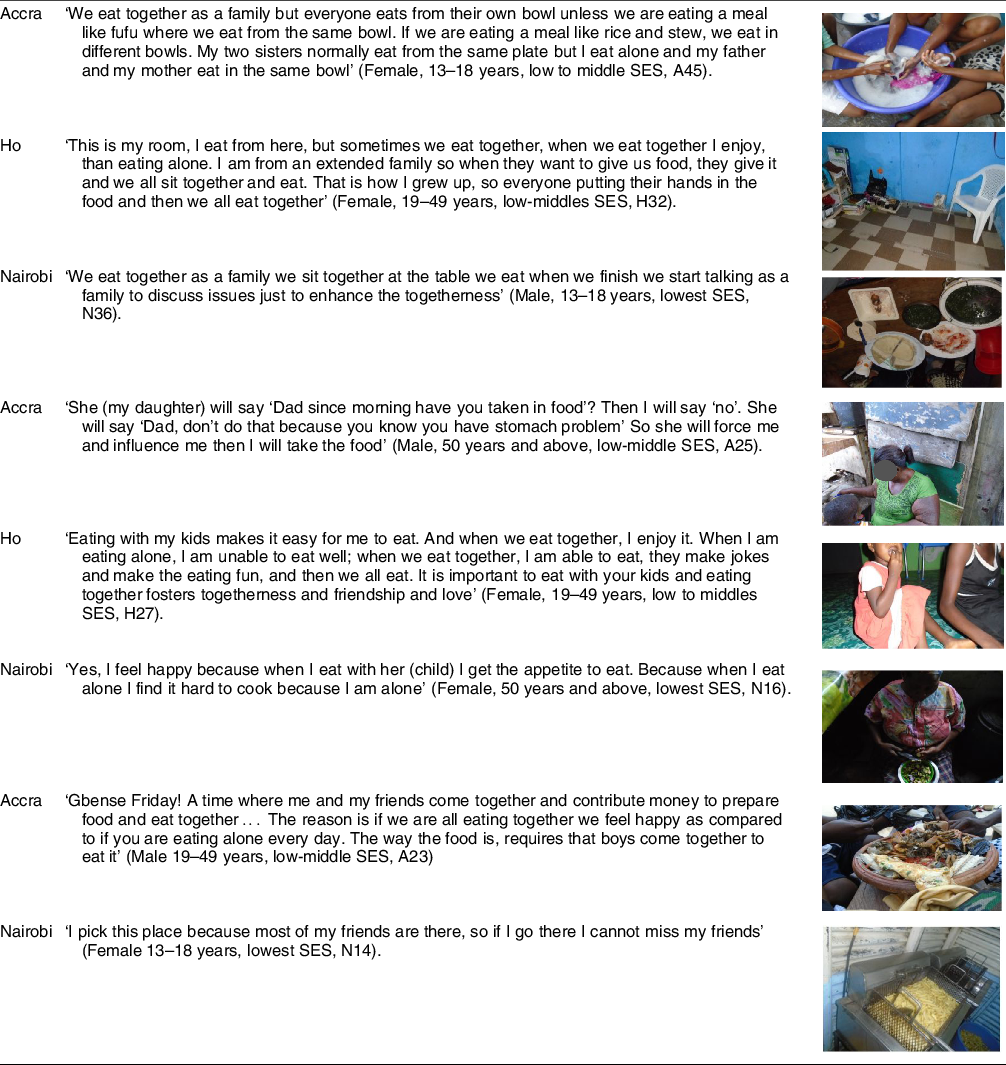

Eating together and company during mealtimes

Eating together habitually as a family was regarded as a moment of joy, bonding, fun, an easy and interesting time or a healthy practice. Some participants also reported that eating with family members facilitates ‘eating well’. Further, eating together was seen as an opportunity where family members connect. In Nairobi, breakfast or dinner was the meals that most families reported eating together, while in Accra, eating from the same bowl was a common family practice, but was not commonly mentioned in Ho or Nairobi.

Some of the participants acknowledged that they enjoyed eating in the company of their family as it improved their ‘appetite’ and fostered love and unity in the family

Older participants in all the three cities particularly reported that their children influenced their dietary behaviour by encouraging them to eat and providing pleasant company during mealtimes. Among the younger participants, in Nairobi and Accra, but not Ho, friends were also reported to provide pleasant and enjoyable company during mealtimes (Table 4).

Table 4 Narratives and photographs on the sub-theme ‘eating together and company during mealtimes’

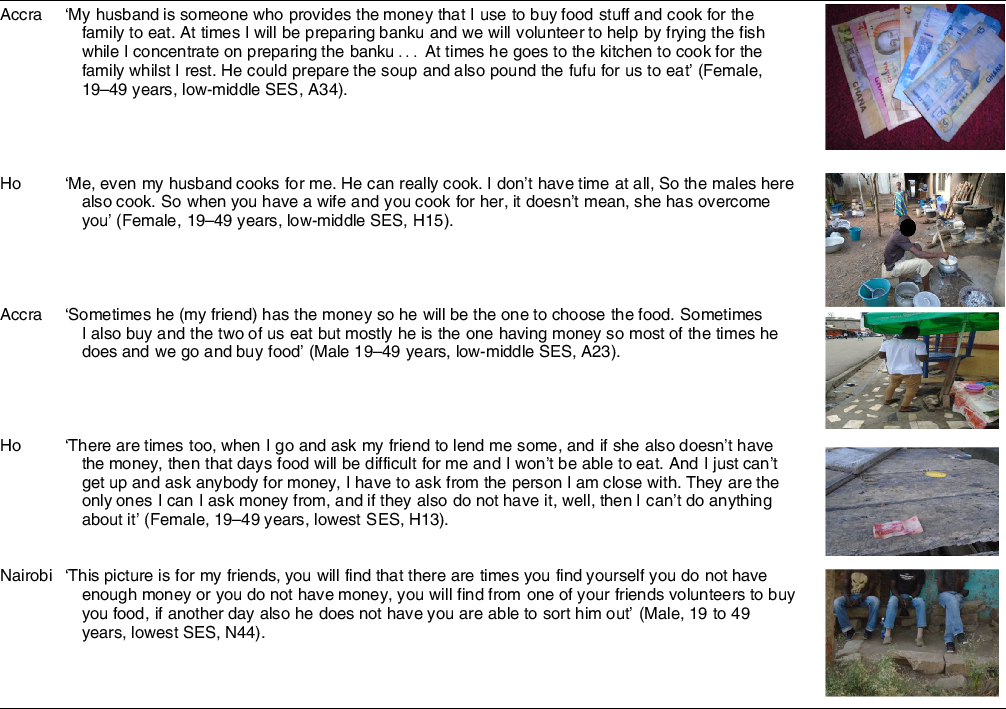

Support with food provision and preparation

Husbands were identified as influencers of dietary behaviours, since they provided money for food purchase and, on some occasions, assisted with food preparation. In both Accra and Ho, female participants reported receiving support from their spouses, with food preparation, but this was not reflected in the narratives from Nairobi.

Younger participants in all three cities also highlighted that their friends influenced their dietary behaviours by buying food for them or by lending them money to buy food (Table 5).

Table 5 Narratives and photographs on the sub-theme ‘support with food provision and preparation’

Nutrition advice and modelling foods behaviours

Parents were commonly mentioned as influencing their children’s food behaviour through providing advice on optimal amounts of food to consume, healthy places to buy food and types of foods to eat and those to avoid, particularly during sickness, pregnancy or lactation. This was more common in Accra and Ho, but less in Nairobi. In addition, parents were reported to model food practices, in Accra and Nairobi (but not Ho), with some participants acknowledging that their preferences of certain foods were based on the foods that they observe their parents eating, preparing, liking or disliking. Some of the younger participants in all the cities further reported that their dietary behaviours were exclusively based on the foods prepared for them by their parents and particularly their mothers, a few reported going along with their parents’ decisions and preferences for family meals even when it was against their own preferences.

Health professionals (nurses, nutritionists and doctors) appeared to influence mainly pregnant women and those with young children, in Nairobi and Accra. This was not reflected in Ho. When visiting health facilities, health professionals advised and encouraged participants to eat certain foods in order to be healthy or promote optimal development for their children. However, a participant in Accra also reported that community nurses advised on food and nutrition targeting children, but not enough for the adult population.

Friends were also mentioned as influencers of younger participant’s dietary behaviour and choices, by advising or encouraging them to eat certain foods (Table 6).

Table 6 Narratives and photographs on the theme ‘support with nutrition advice and modelling food behaviours’

Food vendors’ services and social qualities

In all three cities, the social qualities of local, mainly informal food vendors, largely influenced participants’ decisions on the places where they purchased food. Most participants preferred purchasing from food vendors who are friendly and hospitable, and avoided those who were impolite. Cleanliness of food vendors (referring to their appearance or how they dressed or smelt) and their food handling practices were key considerations by participants when making decisions on where to buy food. Participants in the three cities preferred food from vendors with whom they had established a good relationship, as it led them to trust the quality of foods sold. Food vendors providing credit services were also preferred by most participants, as they would always have access to food even when they did not have enough money. In Accra and Nairobi, provision of additional food services such as cutting /chopping vegetables and packaging were a consideration during food purchasing (Table 7).

Table 7 Narratives and photographs on the theme ‘food vendors’ services and social qualities’

Discussion

This study set out to explore the factors in the social food environment that influence dietary behaviour in urban cities, in Kenya and Ghana. The findings highlight the important role played by the social environment in shaping individual’s dietary behaviours.

Family plays a critical role throughout Africa and is seen as a source of identity and support(25). The impact of family relations including parents, spouses, children, grandparents and siblings on individuals’ health behaviour and wellbeing is documented in other settings(Reference Thomas, Liu and Umberson26). Family socialisation and habits were strong influencers of individual members’ food habits in disadvantaged communities in the United Kingdom(Reference Hardcastle and Blake27), and food selection for the family in urban Ethiopia(Reference Berhane, Ekström and Jirström28). Family members and household structure have also been shown to previously influence food choices and sourcing among Ghana’s urban poor communities(Reference Boatemaa, Badasu and De-Graft Aikins29).

In this study, considerations for specific member’s food preferences were a major influencer on the household’s food purchase, preparation and consumption. For instance, women in their role as ‘mothers’ or ‘wives’ were seen as key influencers of family members’ dietary behaviour by incorporating the nutritional needs and preferences of their family members in food preparation and purchase decisions or by providing nutrition advice to their children. Similarly, women in Singapore reported to consider the health and nutrition needs of their children, and also the food preferences of various family members, especially their children and spouses, while making decisions on food purchase and preparation(Reference Wang, Naidoo and Ferzacca30). In Ethiopia, women acknowledged that they give in to their children’s food preferences as a way of encouraging them to eat(Reference Berhane, Ekström and Jirström28). Results from this study (published elsewhere) further indicated that family food preferences were also shaped by the family’s food access and availability(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23), which explains the preference for foods that most family members liked or could eat, which was seen as convenient, time and resource saving.

Younger participants acknowledged to have their dietary behaviour shaped by their parents’ choices on foods purchased, prepared and consumed by the family. Other studies indicate that parents influence their children’s behaviour through providing food, modelling dietary behaviour or encouraging specific dietary patterns(Reference Cardoso, Santos and Nunes31–Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino33). This influence may also be through exerting authority in food provision in the household or negotiating with children on the foods prepared or available at home(Reference Cardoso, Santos and Nunes31), providing information on food selection and guiding them on good nutrition or preventing them from consuming hazardous food(Reference Korkmaz, Yücel and Yaman32,Reference Banna, Buchthal and Delormier34) . In Accra, it has been reported that mothers influence their children’s food behaviour by teaching them how to cook and choose the foods to eat(Reference Boatemaa, Badasu and De-Graft Aikins29). Health professionals to a lesser extent also influenced individual health and dietary practices, through provision of information and advice, mainly to pregnant and lactating women. Our findings are similar to another study among young adults in Ghana’s Accra city which found that health professionals were among the key sources of nutrition information and were also perceived as the most credible sources of information(Reference Quaidoo, Ohemeng and Amankwah-Poku35). In the smaller city of Ho in our study, this influence was found to be less common. This finding suggests that there is more opportunity for health professionals to influence healthy nutrition in urban populations, especially in smaller city contexts and to broaden nutrition information offered beyond pregnancy and the early years of life(Reference Beagan and Chapman36).

Social relations and support plays an important role in health and diet behaviour. In this study, children and friends appeared to be an important factor among the older and younger participants respectively through provision of food and pleasant company during meals. Eating together as a family was also seen a time for family bonding and interactions. Similarly, in the USA, social support mediated the effect of nutrition interventions in improving dietary behaviour in middle aged and older adults(Reference Yoshikawa, Smith and Lee37) while families that reported to eat their meals together exhibited a higher healthy index score(Reference Schnettler, Lobos and Miranda-Zapata38). A study in South Africa further concluded that individuals who experienced support from their friends and family in adopting a healthy diet were more likely to be motivated to identify healthy eating as their autonomous goals(Reference De Man, Wouters and Delobelle39).

The younger participants in our study reported enjoying the company of their friends, highlighting that it ‘felt good’ eating together and ‘sharing’ some foods, than eating alone. In the same vein, a qualitative study in Lima Peru identified peers as among the key influencers of adolescents dietary behaviour, through sharing of foods such as energy dense snacks and sweetened beverages(Reference Banna, Buchthal and Delormier34). In Indonesia, eating together at school was considered an important social activity in forming and maintaining friendships and peer groups(Reference Roshita, Riddell-Carre and Sjahrial40). A review by Stok et al.(Reference Stok, de Vet and de Ridder41) revealed that peer social norms influence food behaviour and that manipulation of these norms to promote certain food behaviours could yield significant beneficial results. Integrating social support in interventions targeting individual’s nutrition is therefore prudent. Interventions targeting adolescents and youth could also incorporate peer groups as avenues for delivering interventions to promote healthy dietary behaviour in these population groups.

Men in their role as ‘husbands’ or ‘fathers’ were sometimes referred to as providing supportive roles in food provision, purchase and preparation. This indicates that men may have ultimate influence on the food purchased and consumed in the household. A major difference, however, between the Kenya and Ghana cities was the influence that husband or male involvement had on family members’ dietary behaviour, through support with food preparation as reported in the data from Accra and Ho but not in Nairobi. The Nairobi findings are similar to those in previous studies in Uganda, Malawi and Ethiopia, where the role of men is depicted mainly as providing finances for food purchase(Reference Berhane, Ekström and Jirström28,Reference Kansiime, Atwine and Nuwamanya42,Reference Mkandawire and Hendriks43) , with little or no involvement in decision making on foods prepared or consumed in the household. This could be because food preparation and purchase are traditionally viewed as the primary role of women in the African culture. A study in Malawi highlights the challenge of men feeling stigmatised if they are seen to be taking up ‘women’s’ traditional roles, such as food preparation(Reference Mkandawire and Hendriks43). The Malawi study however revealed a progressive shift in gender roles from the perceived traditional role of men as merely ‘financial’ food provision to actively supporting women in food preparation, sourcing and purchase, which aligns with situation observed in Ghana in the current study. Development and enforcement of government policies to encourage greater male involvement in food and nutrition issues as well as gender equality advocacy programmes were some of the strategies employed in central Malawi, to enhance men involvement in food and nutrition issues(Reference Mkandawire and Hendriks43), which could also be applied in other settings.

It was apparent in this study that food vendors have influence on individuals’ choices on food sourcing and provisioning. Food vendors play an important role in urban food systems, since a significant proportion of the food consumed by the urban poor is retailed by street vendors(Reference Tukolske, Kwaw and Blekking44). In a review by Pawel et al. (2012), characteristics of food sellers, including their friendliness and courteous service, were identified as determinants of the place of food purchase by consumers(Reference Paweł and Sikora45). In our study, food safety, especially hygiene and sanitation in the food outlets, was raised as a concern by the study participants as discussed in a separate publication(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23) which may explain the preference for food vendors who appeared clean and prepared their foods hygienically. A Photovoice study with adolescents in urban Ethiopia also highlighted food vendors hygiene as a major consideration and influencer of their dietary behaviour(Reference Trübswasser, Baye and Holdsworth19). Other studies document that consumers’ relationship with food suppliers influences their choice of food purchase; long-term relationships and food supplier’s reputation are among the key considerations of clients(Reference Grunert46). In Accra, consumers have been reported to be motivated by relationships with food vendors and good customer care practices when making food purchase decisions(Reference Antwi-Agyei, Peasey and Biran47). Urban low-income settings in Ghana and Kenya are prone to food insecurity(Reference Tukolske, Kwaw and Blekking44,Reference Kimani-Murage, Schofield and Wekesah48) , and buying food through credit is a common coping strategy for food insecure households in urban settings(Reference Asesefa Kisi, Tamiru and Sinaga49,Reference Drysdale, Moshabela and Bob50) . In addition, results from this study also highlighted economic barriers to food access and overpricing of food products by some of the local food vendors as a potential hindrance to healthy eating(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23). This may explain the preference for food vendors who offer goods and services on credit in this study. In Ethiopia, buying food from food vendors who provide services such as packaging food in small and cheaper portions, and also credit services were reported as coping strategies for families experiencing food insecurity(Reference Berhane, Ekström and Jirström28). Developing, implementing and enforcing hygiene and safety regulations for food outlet owners were recommended by the participants in this study to ensure that food vendors maintained cleanliness as highlighted in a previous publication(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23). In addition, inclusion of food vendors in interventions aimed at improving populations’ dietary behaviour through provision of and increased access to healthier, hygienic and safer foods, will be prudent, given their influence on food purchase and dietary behaviour.

Strengths and limitations

It is recommended that repeated group discussions are conducted throughout a Photovoice project to facilitate the community’s full engagement in the research. In our project however, only individual in-depth interviews were conducted due to logistic constraints of it being too difficult to find convenient times when a group of the urban low-income participants could come together frequently given other constraints on their time. We acknowledge this as a limitation, but we strived to ensure community engagement via separate community events. For example, a photography exhibition was held in each city to raise awareness of the drivers of unhealthy food consumption in the targeted low-income communities. The photography exhibitions served as a platform for community dialogue between study participants, the media and local government officers, during which, issues in their food environment and policy implications were discussed(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23). The qualitative study we conducted focused on understanding individual, social, physical and macro-level drivers of dietary behaviours. One paper combining all levels and describing the interactions between these four levels would have provided valuable information. However, we conducted 142 in-depth interviews across the three cities and gathered a large volume of data and photographs which provided a detailed, rich and comprehensive account of the drivers of dietary behaviours in the targeted African cities. As such, we wanted to describe in an in-depth manner those influences and pathways through which these factors may influence dietary behaviour and hence the choice to split the different components of the study into different papers(Reference Pradeilles, Irache and Wanjohi23).

A key strength of this study is that it provides empirical findings from three cities in two African countries. Using the Photovoice methodology allowed participants to visually present social issues that influence their dietary behaviour. It also allowed active participation of respondents in the data collection, not only as mere respondents but playing an active role in identifying, capturing and describing the social influencers of their dietary behaviour that they perceive as important. The photographs taken by the participants allowed the research team to better appreciate the issues presented and hence facilitate richer discussions on these issues. This approach was enriching to the quality of the data collected and presented in this paper.

Policy implications

In cognisance of the role that the family plays in influencing individual members’ dietary behaviours, interventions focusing on enhancing dietary behaviour at the individual level should consider and leverage the existing household and family structure, and their interconnectedness to be successful. In addition, friends and peers were common influencers of food consumption behaviour among younger participants. As such, peer groups may be considered as effective avenues for delivering interventions targeting adolescents. Food vendors influence food purchase behaviour. Empowering them to provide healthier and safer food options could also enhance healthier food sourcing, purchasing and consumption in African low-income urban communities. Healthcare workers influence nutrition knowledge, through provision of nutrition advice predominantly to pregnant and lactating mothers and mothers with young children, revealing a gap in the interaction with healthcare workers regarding diet for those not falling into these categories. The aspects of the social food environment highlighted in this study, how they influence dietary behaviour, and the population groups that they are most relevant to, should be considered when developing context and population-specific interventions to enhance healthier dietary behaviour.

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the data collection and management team, the community mobilisers and the study participants from Nairobi, Accra and Ho. Financial Support: This work was supported by two funders. The ‘Dietary transitions in Ghana’ project was funded by a grant from the Drivers of Food Choice Competitive Grants Programme [grant number OPP1110043], which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Seattle, WA and the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, and managed by the University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health, USA. The TACLED project was funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) Foundation Award led by the MRC [grant number MR/P025153/1], and supported by Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research (BBSRC), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). The funders played no role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report or the decision to submit for publication. Authorship: M.H., P.G., N.B., M.G., A.L., F.Z., E.K.M., E.K.R., M.B., K.M., R.Ak, R.Ar and R.P. designed the research study. All authors were involved in designing the data collection approach and tools. M.N.W., A.T., S.K., N.C. collected and transcribed the data. M.N.W., P.G., R.P., A.T., S.K., A.I., and F.G. analysed the data. M.N.W. wrote the first draft of the paper with critical input from P.G., R.P., M.H. and G.A. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (references: GHS-ERC 07/09/16 and GHS-ERC 02/05/17) in Ghana and the African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF) (reference: ESRC P365/2017) in Kenya. The ethical committees granted permission for photographs re-use in scientific outputs. Approvals from UK research institutions included The University of Sheffield, Loughborough University (R17-P142) and the University of Liverpool (1434 and 2288). Written informed consent was obtained from participants who were aged 18 years or older and assent from legal guardians of participants aged 13 to17 years. A photograph release form was used to request consent to take photographs if a person’s face was visible, and participants consented to photographs being used in scientific outputs.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in the manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022002270