Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide and will impose a great burden on health-care systems in future decades( Reference Roger, Go and Lloyd-Jones 1 , Reference Smith, Horgan and Sexton 2 ). Despite numerous epidemiological data on stroke prevalence in the USA and Western countries( Reference Roger, Go and Lloyd-Jones 1 , Reference Smith, Horgan and Sexton 2 ), little information is available from population-based studies in developing countries( Reference Hata and Kiyohara 3 ). Findings from prior investigations in Iran have revealed that the incidence of stroke is greater than in most Western countries, with stroke occurring at younger ages and ischaemic stroke being more prevalent than other subtypes( Reference Azarpazhooh, Etemadi and Donnan 4 ). Therefore, primary prevention of stroke is of great priority in these countries.

Dietary intake of several nutrients and foods has previously been linked to stroke; therefore, dietary modification may be a crucial way to reduce risk of stroke. Meat is widely used in the diet globally and is a main source of protein and some other nutrients in most diets. Earlier evidence from epidemiological studies has indicated that high consumption of red meat, particularly processed meat, might contribute to cancer( Reference Egeberg, Olsen and Christensen 5 ), CHD( Reference Ashaye, Gaziano and Djousse 6 ), type 2 diabetes( Reference Lajous, Tondeur and Fagherazzi 7 ) and the metabolic syndrome( Reference Azadbakht and Esmaillzadeh 8 ). High intake of red meat is also significantly associated with the prevalence of hypertension( Reference Tzoulaki, Brown and Chan 9 ) and dyslipidaemia( Reference Azadbakht and Esmaillzadeh 8 ), two well-known risk factors for stroke.

Epidemiological data on the relationship between red meat consumption and stroke are sparse and inconsistent( Reference Larsson, Virtamo and Wolk 10 – Reference He, Merchant and Rimm 13 ). A published meta-analysis of cohort studies reported no significant association between consumption of red and processed meats and stroke( Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian 14 ); whereas findings from another recent meta-analysis of five cohort studies revealed that high red meat intake is associated with a 9 % increase in the risk of stroke( Reference Chen, Lv and Pang 15 ). Each of these two meta-analyses included only one investigation conducted in an Asian population, which may not reflect the associations that typically exist in the Middle Eastern region. In a prospective cohort study of 51 683 Japanese adults( Reference Nagao, Iso and Yamagishi 16 ) that was not included in the previously mentioned meta-analyses( Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian 14 , Reference Chen, Lv and Pang 15 ), the authors found no link between moderate consumption of meat (including beef, pork, poultry, liver and processed meat) and mortality from stroke. Therefore, further evidence is required to clarify the possible relationships.

Almost all previous studies on the relationship between red meat intake and stroke have been done in developed countries, where dietary intakes of red and processed meats are high. Data in this regard are lacking from developing nations, in particular from the Middle Eastern populations whose dietary intakes of meat might be low to moderate. Moreover, the major sources of red meat intake in these countries are different from those developed countries, where pork is a major source of red meat intake. Some studies have indicated that the source of red meat intake may contribute to the association between red meat intake and CVD events( Reference Takata, Shu and Gao 17 ). Furthermore, the dietary intakes of Iranians are greatly different from those in Western countries( Reference Esmaillzadeh and Azadbakht 18 ) and investigating the red meat–stroke association in this diversified mixed diet might provide additional information. Since findings from epidemiological studies are better replicated in a different range of dietary intakes in different populations, we hypothesized that red meat intake might contribute to the increasing prevalence of stroke among the Iranian population. Given the paucity of data on diet–disease relationships in the understudied population of the Middle East, we examined the association between red meat consumption and stroke in a group of Iranian adults.

Materials and methods

Participants

The current hospital-based case–control study included 195 stroke patients and 195 hospital controls. All participants were recruited from Alzahra University Hospital, Isfahan, Iran. Data about all cases and controls in the study were collected between January and December 2008. Data on each pair of cases and controls were collected at the same time. Cases were selected through a convenience non-random sampling procedure. They were stroke patients who were hospitalized in the neurology ward of Alzahra University Hospital. Controls were selected from hospitalized patients in orthopaedic or surgical wards of this centre. They were without a prior history of cerebrovascular accident or any neurological disorders and were not hospitalized owing to vascular-related conditions. The participation rate in the study was 100 % for cases and 93 % for controls. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Assessment of dietary intake

A validated 168-item FFQ was used to assess the intakes of foods usually consumed by the participants over the previous year( Reference Esmaillzadeh, Kimiagar and Mehrabi 19 ). All questionnaires were administered by trained dietitians. The quantity of the food consumed was assessed by asking a standard common portion size. As brain damage or impaired memory is the most common sequela of stroke and recalls of dietary intakes from these patients might be distorted, we asked their family members to help complete the FFQ. The reported frequency as well as the portion size was double checked with the person responsible for cooking at home. The daily frequency of foods was calculated by dividing weekly frequency consumption by seven and monthly frequency by thirty, and the average daily intake of foods and beverages was calculated by multiplying the portion size by the daily frequency of consumption. Total energy intake was calculated by summing up energy intakes from all foods. Total red meat consumption was calculated by summing up the consumption of red meat (beef, veal, mutton, lamb), processed meat (sausages, hamburgers, hot dogs) and visceral meats (lamb’s liver, kidney, heart).

Assessment of stroke

Patients aged >45 years with first ever symptomatic acute stroke diagnosed by a neurologist and confirmed by brain computerized tomography scanning or MRI were included. Patients with head trauma, primary intracranial haemorrhage, or subarachnoid or subdural haemorrhage were excluded. Data were collected by prospective chart review from January 2008 to December 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Bioethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Assessment of other variables

Required information on non-dietary variables such as socio-economic and demographic characteristics (sex, age, education and occupation), past and family medical history, physical activity and smoking status was collected by the use of questionnaires. Height measurement was done in bare feet, weight measurement was done in light clothing and, finally, BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight divided by height squared.

Statistical methods

To ensure normal distribution of variables, we applied the Kolmogrov–Smirnov test. We used two approaches in data analysis: (i) all comparisons were done between cases and controls; and (ii) all comparisons were also performed across tertiles of red meat consumption. Student’s t test was used for comparing the means of continuous variables between cases and controls. The χ 2 test was applied to the compare distribution of participants between the two groups in terms of categorical variables. Energy-adjusted amounts of red meat intake were calculated using the residual method. Then, tertile cut-off points of energy-adjusted red meat intake were used for categorizing participants. General characteristics and dietary intakes of participants between cases and controls as well as across tertiles of red meat intake were compared by the use of ANOVA and the χ 2 test, where appropriate. All dietary intakes were obtained using general linear models with age and total energy intake as covariates. The logistic regression method was used to examine the associations between red meat consumption and risk of stroke. Estimates are presented in four models. The first model was adjusted for age (continuous), sex (categorical) and total energy intake (continuous). In the second model, we controlled for physical activity (continuous) and smoking (never, ex-smokers, daily smokers). Additional adjustments were made for dietary intakes (including whole and refined grains, vegetables, fruits, low-fat and high-fat dairy, hydrogenated vegetable oil, butter and margarine, nuts and legumes, sugar-sweetened beverages and potato, all as continuous variables) in the third model. Finally, we further adjusted for BMI (continuous), diabetes (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no) and hyperlipidaemia (yes or no) in the fourth model. When the analyses were done across tertiles of red meat intake, the first tertile of red meat consumption was considered as the reference. The overall trend of odds ratios across tertiles of red meat consumption was examined through the use of tertile categories as an ordinal variable in the model. Statistical analyses were performed by using the statistical software package SPSS version 16·0. For all analyses, a value of P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

All participants with energy intake less than 3347 kJ (800 kcal) or more than 17 573 kJ (4200 kcal) were considered as under- and over-reporters, respectively. Overall, eleven participants could be excluded due to being under- and over-reporters. As in our preliminary analysis the exclusion of this small group of participants did not significantly influence our findings, we decided not to exclude any FFQ.

General characteristics of the study participants based on case and control groups as well as across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intake are indicated in Table 1. Participants with stroke were more likely to be male (60 % v. 47 %, P<0·05) and older (67·9 (se 1·0) years v. 61·5 (se 0·8) years, P<0·001) than controls. They had lower weight (69·5 (se 0·9) kg v. 72·4 (se 1·1) kg, P<0·05), BMI (25·2 (se 0·3) kg/m2 v. 28·5 (se 1·0) kg/m2, P<0·05) and were less likely to be obese (11·3 % v. 29·2 %, P<0·001) compared with controls. Hypertension was more prevalent among those with stroke than among controls (65·8 % v. 27·2 %, P<0·001). In addition, compared with those in the lowest category, participants in the highest category of red meat consumption had higher weight and were more likely to be male, physically active and current smokers. No significant differences were found in terms of mean BMI and prevalence of obesity across tertiles of red meat intake. The use of medication among cases was listed as follows: aspirin 12·0 %, persantine 1·3 %, warfarin 5·2 %, plavix 1·5 %, antihypertensives 26·3 %, statins 7·7 %, oral hypoglycaemic agents 8·8 %, insulin 2·1 %, other drugs 19·8 %.

Table 1 General characteristics of the study participants based on case and control groups as well as across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intakeFootnote *; Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008

MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

* Data are means and their standard errors unless indicated otherwise. P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

† BMI≥30·0 kg/m2.

‡ Obtained by the use of ANOVA or the χ 2 test, where appropriate.

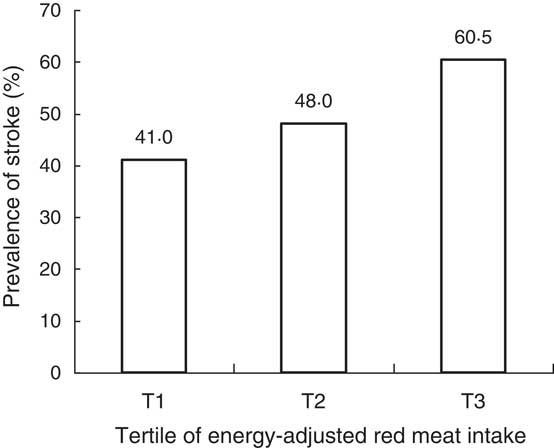

The prevalence of stroke across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intake is shown in Fig. 1. Red meat intake was associated with high prevalence of stroke; such that individuals in the top tertile of red meat intake had higher stroke prevalence compared with those in the bottom tertile (60·5 % v. 41·0 %, P=0·007).

Fig. 1 Prevalence of stroke across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intake among group of Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008 (P=0·007, ANOVA)

Dietary intakes of the study participants based on case and control groups as well as across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat consumption are provided in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Cases with stroke had higher intakes of high-fat dairy, fruits, legumes and nuts, and lower intake of low-fat dairy than the controls. Higher consumption of red meat was associated with higher intakes of energy, fruit and vegetables, low-fat dairy, sugar-sweetened beverages, nuts and legumes, and grains. No significant differences were found for other dietary variables across tertiles of red meat intake.

Table 2 Dietary intakes of the study participants based on case and control groupsFootnote *; Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008

* Data for energy intake are adjusted for age. Data for other dietary variables are adjusted for age and total energy intake. P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

† Obtained by the use of ANCOVA.

Table 3 Dietary intakes of the study participants across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intakeFootnote *; Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008

* Data for energy intake are adjusted for age. Data for other dietary variables are adjusted for age and total energy intake. P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

† Obtained by the use of ANCOVA.

Crude and multivariable-adjusted odds ratios for stroke based on case and control groups as well as across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intake are indicated in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Red meat intake was significantly associated with the risk of stroke; such that each tertile of red meat intake was related to 90 % increased odds of stroke, after adjustment for confounders (OR=1·90; 95 % CI 1·71, 2·85). Moreover, in the crude model, individuals in the highest tertile of red meat intake were 119 % more likely to have stroke (OR=2·19; 95 % CI 1·33, 3·60) compared with those in the lowest tertile. After controlling for age, sex and total energy intake, the association between red meat consumption and stroke was strengthened (OR=2·72; 95 % CI 1·53, 4·83). This association remained significant even after further controlling for physical activity and smoking as well as dietary intakes. Additional adjustments for BMI, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia did not influence the association significantly; such that participants in the highest tertile of red meat consumption had 151 % greater odds of stroke than those in the lowest tertile (OR=2·51; 95 % CI 1·19, 5·09).

Table 4 Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for stroke based on case and control groupsFootnote *; Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008

* P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

† Adjusted for age, sex and energy intake.

‡ Further control for physical activity and smoking.

§ Further adjustments for whole and refined grains, vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy, high-fat dairy, hydrogenated vegetable oil, butter and margarine, nuts and legumes, sugar-sweetened beverages and potato intake.

|| Additionally adjusted for BMI, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Table 5 Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for stroke across tertiles of energy-adjusted red meat intake; Iranian adults aged >45 years, January–December 2008

* Adjusted for age, sex and energy intake.

† Further control for physical activity and smoking.

‡ Further adjustments for whole and refined grains, vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy, high-fat dairy, hydrogenated vegetable oil, butter and margarine, nuts and legumes, sugar-sweetened beverages and potato intake.

§ Additionally adjusted for BMI, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

|| Obtained by the use of tertile categories of red meat intake as an ordinal variable in the model. P<0·05 was considered as statistically significant.

Discussion

In the present case–control study, we found that consumption of red meat was significantly and positively associated with the risk of stroke among a group of Iranian adults. This unfavourable relationship was significant after controlling for different confounding variables, indicating a covariate-independent association. To the best of our knowledge, the current investigation is the first one reporting the association between red meat intake and risk of stroke in a Middle Eastern population.

Stroke is an important cause of mortality and disability globally. Among various dietary components suggested as important modifiable risk factors for stroke, red meat consumption is inconsistently associated with stroke( Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian 14 – Reference Nagao, Iso and Yamagishi 16 ). While earlier studies have found a positive association between red meat intake and increased risk of stroke, even at a low intake of one serving per day( Reference Larsson, Virtamo and Wolk 11 , Reference He, Merchant and Rimm 13 ), red meat intake was not significantly related to incident stroke in other investigations( Reference Sauvaget, Nagano and Allen 12 , Reference Takata, Shu and Gao 17 ). Our study indicated that high consumption of red meat is significantly associated with greater odds of stroke. This is in line with a recently published meta-analysis that summarized the existing evidence from epidemiological studies in North America, Europe and Japan. Findings from the meta-analysis revealed a 15 % increased risk of stroke for red and processed meat intake, 9 % for red meat intake and 14 % for processed meat intake( Reference Chen, Lv and Pang 15 ). Such findings have also been reported in prospective cohort studies. In the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, high consumption of both processed and unprocessed red meat was associated with a greater risk of stroke( Reference Bernstein, Pan and Rexrode 20 ). The positive association between red meat intake and stroke has not been indicated in all previous studies. In a meta-analysis in 2010, a null association between red meat intake and risk of stroke was suggested( Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian 14 ). However, in this meta-analysis only three cohort studies, containing small number of stroke cases (n 2300), were included. A large prospective cohort study conducted among the Japanese population also reported no association between moderate amounts of meat consumption, up to 100g/d, and stroke( Reference Nagao, Iso and Yamagishi 16 ). These investigators had included unprocessed poultry in the total meat calculation; however, high intake of poultry was associated with a lower risk of stroke( Reference Bernstein, Pan and Rexrode 20 ). Therefore, lack of a clear description of types of meat might contribute to the discrepancies observed between studies.

In the current study, we had only nineteen cases of haemorrhagic stroke and the other 176 cases had ischaemic stroke. When we excluded cases with haemorrhagic stroke from the analyses, the results strengthened (top v. bottom tertile of red meat intake: OR=2·97; 95 % CI 1·41, 6·24, P=0·004). Most previous studies have suggested that meat consumption is associated with ischaemic stroke, not with haemorrhagic stroke( Reference Chen, Lv and Pang 15 ). The different aetiologies of stroke subtypes may be linked differently to risk factors including dietary factors. In addition, the number of patients with haemorrhagic stroke included in most studies was smaller than the number with ischaemic subtype, and thus may limit statistical power and the ability to detect a modest association between meat intake and haemorrhagic stroke. In terms of the types of red meat intake, earlier studies have found stronger associations with processed meats than with unprocessed meats( Reference Chen, Lv and Pang 15 , Reference Bernstein, Pan and Rexrode 20 ). In the present study, the red meat category was computed by summing up both processed and unprocessed red meats. We did not include poultry and fish intake in this computation. However, as consumption of processed meats was low (mean: 2·24 g/d), we did not consider that as a separate category.

Several potential mechanisms may explain the adverse effect of red meat consumption on stroke. Red meat is a major source of haem Fe. In an experimental study, the intracellular Fe chelator, desferrioxamine, has been suggested to inhibit inflammation and atherosclerosis, suggesting a potential role of Fe in atherosclerosis( Reference Zhang, Wei and Frei 21 ). Elevated haem Fe stores may cause oxidative injury. Epidemiologically, Fe intake has been associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis( Reference Wolff, Volzke and Ludemann 22 ), insulin resistance( Reference Jiang, Manson and Meigs 23 ), type 2 diabetes( Reference Jiang, Manson and Meigs 23 ) and CHD( Reference Micha, Wallace and Mozaffarian 14 ); all may contribute to the increased risk of stroke. Processed and unprocessed red meats contain high amounts of dietary cholesterol, which has been shown to have adverse effects on serum lipid profiles and subsequently may increase the risk of stroke( Reference Wolff, Volzke and Ludemann 22 ). Furthermore, consumption of red meat was positively associated with risk of hypertension( Reference Tzoulaki, Brown and Chan 9 ), the strongest well-known risk factor for stroke. Na content of processed meats may also explain the positive association observed between meat consumption and risk of stroke( Reference Strazzullo, D’Elia and Kandala 24 ).

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of potential limitations. Due to the case–control design of the study, causality cannot be inferred. Misclassification of the study participants, as a result of using an FFQ for dietary assessment, could be considered a concern, as it is in most nutritional epidemiology studies. However, the FFQ had previously been validated( Reference Esmaillzadeh, Kimiagar and Mehrabi 19 ). In addition, due to using an FFQ for assessing intakes, we could not exactly measure individuals’ salt intake in order to include it in principal component analysis or make adjustment for it. As we used hospital-based controls in the study, we cannot claim with certainty that controls are representative of healthy adults. In the present study, we did not collect data on cooking methods that might alter health effects of red or processed meats( Reference Bogen and Keating 25 ). Despite the comprehensive adjustment for confounders in our analyses, some other confounders such as waist circumference and family history of stroke could not be considered due to the lack of data in this regard. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. Finally, since we did not perform scanning or imaging in control participants, some controls who might have experienced a silent asymptomatic ischaemic stroke could not be excluded. However, they had no such history, and their examinations were normal.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that consumption of red meat was associated with greater odds of stroke in a group of Iranian adults. This association was independent of potential confounders. Further prospective investigations are needed to confirm this finding.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was supported by a grant from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Islamic Republic of Iran (no. 187028 IUMS). Financial support for conception, design, data analysis and manuscript drafting comes from the Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. The Food Security Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: P.S., M.S., A.H.K. and A.E. contributed in the conception, design, statistical analyses and drafting of the manuscript. F.S., A.H.K. and M.S. contributed in data collection. M.B. helped in manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. A.E. supervised the study. Ethics of human subject participation: All participants provided informed written consent. The study was approved by the Regional Bioethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.