Adolescence is a period that involves physical, psychological and social changes among female and male adolescents, along with changes in body composition(Reference Filgueiras, Cecon and Faria1). Perhaps, adolescents may be more vulnerable to body image disorders. These natural body changes can cause adverse effects of body dissatisfaction on the emotional well-being and might be more frequent in this stage of life. Body image disorder has been considered as a public health concern in its own right(Reference Griffiths, Murray and Bentley2). In addition, female adolescents tend to be influenced by media and their socio-cultural environment to reach a lean shape with low body fat, and male adolescents are driven to muscle definition(Reference Amaral, Conti and Ferreira3,Reference Duchin, Mora-Plazas and Marin4) .

Body image is defined by how individuals perceive or feel in relation to the size and contour of their own body(Reference Cash and Cash5). Body image disturbances are severe and cause persistent changes in perception and attitude, like body dissatisfaction and distortion, which can lead to social, physical and emotional suffering and/or impairment(Reference Rohde, Stice and Nathan Marti6). Severe cases of body image disorders, associated with other factors, can trigger unhealthy behaviour, such as eating and body dysmorphic disorders(Reference Golden, Schneider and Wood7).

Recent studies in Brazil have shown that nearly one-half of female adolescents(Reference Miranda, Morais and Faria8) are more often dissatisfied with their body image than male adolescents are(Reference Miranda, Morais and Faria8,Reference Morais, Miranda and Priore9) . According to Miranda et al.(Reference Miranda, Morais and Faria8), female adolescents with elevated BMI were 3·26 times more likely to present body dissatisfaction than those with adequate or low BMI. Furthermore, spending more than 2 h in front of a screen (screen time (ST)) on a daily basis may have a strong association with body image dissatisfaction, with that investigation having shown an increase in the occurrence of dissatisfaction by a factor of 1·83 when the ST exceeded 2 h. Many Brazilian studies have investigated the association of different factors with body dissatisfaction. However, there is a need to evaluate other disorders of body image such as body perception distortions and negative cognitive evaluation of body image, especially in association with body composition, lifestyle and behaviour in adolescents.

The sedentary lifestyle in adolescence, combined with inadequate and unbalanced food intake, may result in elevated BMI(Reference Dunker and Claudino10). Also, these factors are associated with body image disorders. Furthermore, high leisure ST, healthy eating pattern and balanced daily activity behaviours (physical activity (PA) and sedentary behaviour) can be associated with anxiety symptoms, self-esteem, suicide ideation, loneliness, depressive symptomatology and psychological distress(Reference Silva and Menezes11). These, though controversial, are predominant factors in the development of body dissatisfaction and distortion, especially in female adolescents(Reference Farhat12).

According to Shirasawa et al.(Reference Shirasawa, Ochiai and Nanri13), the lifestyle chosen by female adolescents can be associated with their body composition and negative body image evaluation. However, there is a paucity of conclusive information disclosing the emotional and physical health dimensions of the adolescents, especially the relationship between body image, body composition and different measures of lifestyle, like physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour(Reference Silva and Menezes11). Nowadays, body image disturbance is an even larger public health problem(Reference Bornioli, Lewis-Smith and Smith14) among adolescents. Body dissatisfaction, distortion and excessive concern with appearance can also be associated with risk behaviours such as smoking, drug use (notably cannabis), self-harm, gambling and drinking(Reference Bornioli, Lewis-Smith and Smith14).

These variables must be researched more carefully because adolescents can develop health issues in physical, mental and emotional dimensions, which have a deleterious impact on the adult phase of the individual and can damage longevity. Thereby, this is a cross-sectional, descriptive and analytical study whose purpose was to assess the association between body image disorders with lifestyle and body composition of female adolescents.

Materials and methods

The study population consisted of female adolescents who were 14–19 years old, who were residents of and attending public schools in Viçosa city (state of Minas Gerais, Brazil). Public high schools were queried about the number of female students aged between 14 and 19 years; in 2014, there were 1657 students in this age range.

A cluster sampling plan was used, proportionally to the number of adolescents enrolled in the selected public schools (clusters). This sampling procedure is a probabilistic technique in which sample units are clusters of elements (adolescents). Thus, all eligible students regularly enrolled in the selected schools were invited to participate in the study. A design effect estimated at 1·1 was introduced to correct the variance of parameter estimates, accounting for intra-cluster correlations. A value >1 for the design effect indicates that the sample design used is less efficient than simple random sampling.

From this information, sample size was calculated using the StatCalc software programme EpiInfoTM, version 7.2.0.1 (2012). The sample size was calculated for a 95 % confidence level, with a prevalence of 35·6 %(Reference Morais, Miranda and Priore9) of negative body dissatisfaction in female adolescents in the intermediate and final phases of adolescence, and a maximum error of 5 %. The estimated minimum sample size was 318 individuals, with an additional 20 % to cover possible losses; the final recommended number of participants was 382 adolescents. First, all female adolescents were invited to participate in the study. Soon after, the volunteers were randomly selected to begin the process of analysis.

To participate in the study, the adolescents needed to accept voluntarily, to have signed permission from their guardian if under 18 years old, to have had menarche in the prior year, to have no previous knowledge of any type of chronic or infectious disease, and not to be under controlled medication. Also, the participant could not be part of another research evaluating body composition or nutritional status.

Each volunteer only took part in the project after turning in the Assent Form and the Informed Consent Form signed respectively by herself and by her parents or legal guardians. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data collection procedures

Data collection began in June 2014 and ended in December 2015. The first stage of the survey took place in schools, where management had been previously consulted and informed about the study. After consent, students were contacted for a detailed explanation of all the procedures and for delivery of the Free and Informed Consent Form and the Term of Assent, both to be duly signed and returned afterwards. These forms contained detailed descriptions of all steps to be taken, as well as the guarantee of security, confidentiality and privacy for all information collected. Socio-demographic information and indicators of alcohol and tobacco consumption were collected by members of the research project. From the date of birth, ages were calculated through the WHO AnthroPlus software and categorised as middle (from 14 to 16 years) and late adolescence (17–19 years)(15). Socio-economic classification was based on the questionnaire proposed by the Brazilian Association of Survey Companies(Reference Miranda, Amorim and Bastos16).

The lifestyle assessment protocol was explained in detail to the participants; it began with the monitoring of PA and sedentary behaviour levels for 8 d and was completed after a body composition and body image analysis.

The assessment of body composition and body image, conducted at the Health Division of the Federal University of Viçosa, purposely took place after lifestyle monitoring so that there was no stimulus that could encourage artificial behaviour changes. While the adolescents were fasting, their body fat percentage (BFP) was measured by a Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry equipment. Other anthropometric measurements were also performed in the fasting period.

After eating a breakfast offered by the HD, the adolescents were informed of the protocol for questionnaire-based body image evaluation. In some situations, this body image assessment took place at the participants’ own school.

Lifestyle assessment

Lifestyle was considered a latent variable, that is, not directly observable, and was evaluated by latent class analysis (LCA)(Reference Linzer and Lewis17). With the information from the manifested variables, we elaborated on a statistical model that allowed estimating the probability of a given individual belonging to each of the latent variable categories(Reference Flynt18).

In this study, the lifestyle LCA variables were PA, sedentary behaviour, number of meals, alcohol and tobacco consumption. All these variables were evaluated during eight consecutive days. The first day of evaluation was discarded to minimise the Hawthorne effect, which consists of changing behaviour to fulfil the expectations of the study(Reference Corder, Ekelund and Steele19).

The PA was evaluated by the Digiwalker SW 200 pedometer, using a cut-off value of 11 700 to determine if the number of steps could be considered an active or inactive behaviour(Reference Corder, Ekelund and Steele19,Reference Tudor-Loocke, Craig and Beets20) . The 24-h recall complemented this evaluation(Reference Bratteby, Sandhagen and Fan21). The pedometer recorded participant’s scored activities performed in a 24-h period (every 15 min); moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) were defined as those with a metabolic equivalent equal to or above 3. The metabolic equivalent corresponds to the metabolic-rate multiple needed for an individual to remain at rest. For this study, the adequate average daily time for MVPA considered was at least 60 min(22).

The sedentary behaviour was assessed by ST, cell phone screen time (CT) and sitting time during weekdays and weekends. ST and CT were measured according to the questionnaire proposed by Miranda et al.(Reference Miranda, Morais and Faria8) which evaluates the time spent per day in front of television, computer, video game and tablets. CT was analysed separately from the other electronic devices; however, both analysis classified the activities as high when the mean time in the evaluated days was ≥120 min/d, which is the standard time defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics(23).

We analysed the sitting time during weekdays and weekends according to section four of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire(Reference Guedes, Lopes and Guedes24). The weighted average of both data allowed us to estimate the sitting time of both weekdays and weekends. The 75th percentile (75th P) was used as the reference value for sitting time classification due to the lack of a specific cut-off point. The 75th P for all days assessed was 585 min.

The number of daily meals was recorded based on breakfast, collation, lunch, afternoon snack, dinner (or snack) and supper. The mean value during the 7 d was calculated and later categorised by the 50th percentile (50th P = 4·0). Values lower than 25thpercentile were considered small number of meals.

Alcohol and tobacco consumption were observed by two short modules of the Global School – Based Student Health Survey(Reference Tenório, Barros and Tassitano25). The answer option represented by the letter ‘a’ for all questions showed that the teenager had never had any type of alcohol and tobacco use. The other responses were coded with a numerical score of increasing order to be able to quantify the consumption of alcoholic beverages and exposure to tobacco.

Body composition assessment

All the anthropometric measures were performed by a female research member previously trained. Weight was measured in an electronic digital (Kratos®) scale, and height was measured with a portable stadiometer (Alturexata®). Subsequently, BMI was calculated by Z-score in the Who AnthroPlus software. The BMI classification was based on the cut-off points proposed by De Onis et al.(Reference De Onis, Onyango and Borghi26).

Total BFP was evaluated with a Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry equipment (Lunar Prodigy Advance DEXA System – analysis version: 13.31, GE Healthcare), during fasting. The BFP classification followed the cut-off points proposed by Williams et al.(Reference Williams, Going and Lohman27). A BFP above 30 was considered high.

Three body composition assessment groups were created from BMI and BFP data. Group 1 was composed of adolescents with low weight – eutrophy and adequate BFP; Group 2, eutrophy – high BFP; Group 3, elevated BMI and high BFP.

To measure the waist circumference, we used a 2-m, flexible and inelastic measuring tape (Cardiomed®), divided into centimetres and subdivided into millimetres. Measurements started at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last rib and the iliac crest, in the horizontal plane. The 90th percentile (90th P) was used as cut-off for the waist circumference classification. The waist-height ratio (WHtR) was obtained by the relation between waist measurement (cm) and height (cm). The cut-off point adopted for classification of WHtR was 0·5, with variations suggested by Ashwell & Gibson(Reference Ashwell and Gibson28): low WHtR <0·4; appropriate WHtR between 0·4 and 0·5; high WHtR between 0·5 and 0·6; very high WHtR >0·6.

Body image assessment

Adolescent body image was evaluated through the Silhouette Scale(Reference Laus, Almeida and Murarole29), the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ)(Reference Conti, Cordas and Latorre30) and the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3)3.

The Silhouette Scale was validated for Brazilian adolescents by Laus et al.(Reference Laus, Almeida and Murarole29). The first figure selected was the one that best represented the current body (current silhouette – C.S.), then the figure that best represented the desired body (ideal silhouette – I.S.). Body satisfaction was assessed by the difference between .I.S. and C.S. When this difference was between –1 and +1, the adolescent was classified as satisfied(Reference Laus, Almeida and Murarole29). Body distortion was assessed by the difference between the BMI of the silhouette chosen as current and the actual BMI measured. The difference between the BMI of the SA and the BMI measured was greater or less than 2·49 kg/m2, which is the difference value of the BMI variation of the figures. A difference smaller than –2·49 represented negative distortion, and a value greater than +2·49 demonstrated a positive distortion.

The Brazilian version of BSQ validated to adolescents(Reference Conti, Cordas and Latorre30) was used to assess the body dissatisfaction. Each question has six response options, being: 1 – never to 6 – always, and four levels of dissatisfaction with the physical appearance according to the final score (<80 points – no body dissatisfaction, 80–110 points – slight dissatisfaction, 110–139 points – moderate dissatisfaction – 140 points – severe dissatisfaction)(Reference Conti, Cordas and Latorre30).

SATAQ-3 assessed the cognitive dimension of body image. This instrument was validated for the Brazilian adolescent population3 and consisted of thirty questions evaluating four aspects: general internalisation of socially established standards, pressure exerted by these standards, the media as a source of information about appearance and the internalisation of an athletic body ideal. The total SATAQ-3 score was calculated by the sum of the responses, and the highest score represented a greater socio-cultural influence on body image. High SATAQ-3 score classification was done by the 50th percentile (50th P = 80 points), as suggested by Alvarenga et al.(Reference Alvarenga, Dunker and Philippi31).

Statistical analysis

Double data entry was performed by two researchers, then checked and analysed in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corporation®) to check tabulation. We completed the statistical analysis in the STATA software, version 13.0 (StataCorp LP®), and the statistical software R (R Development Core Team, 2014), version 3.2.2 (‘Fire Safety’). The level of rejection of the null hypothesis was of α = 5 %.

LCA was used for modelling the ‘lifestyle’ variable, having been conducted in the poLCA package (Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis) available in the library of the R statistical software (R Development Core Team, 2014). The most adjusted model presented three latent classes, having as manifest variables the practice of MVPA, number of steps, ST, number of meals and total sitting time, and the consumption of alcohol was used as a covariate (Akaike Information Criterion – AIC = 1952·33, Bayesian Information Criterion – BIC = 2024·22, χ 2 = 20·06 (df = 12, P = 0·066) and entropy = 0·79). The model resulted in three lifestyle classes that were named as: Inactive & Sedentary lifestyle (class 1 – γ = 77·5 %); Inactive & Non-sedentary lifestyle (class 2 – γ = 16·31 %) and Active & Sedentary lifestyle (class 3 – γ = 6·15 %)(15).

Following the analyses, the association between body image, lifestyle latent class and body composition was assessed by the χ 2 and Fisher’s exact test. The relationship between lifestyle latent classes and body image measurements was confirmed through simple logistic regression analysis. OR and 95 % CI were used as measures of effect. The variables, age, socio-economic class, sitting time, alcohol consumption and tobacco, were used in the adjustment of the latent lifestyle classes, hence the option to use the gross and not the adjusted OR. To balance the size ratio with class 1, classes 2 and 3 were analysed together in simple and multiple logistic regression analysis.

The multiple linear regression was used to assess the association between aspects of body image with the different lifestyle variables and the measures of the body composition. Before reaching the final multiple models, the simple linear regression was used to select the independent variables. Thus, it was observed that variables with a P value below 20 % (P < 0·20) were inserted in the multiple logistic regression model by the backward method. The Hosmer & Lemeshow test was used to verify the fit of the final model. The adjusted OR with 95 % CI was used as an effect measure.

Results

A total of 405 adolescents participated in all evaluations, with some losses in certain variables. The mean age was 15·92 (±1·27) years old, with 259 individuals (69 %) in the intermediate phase. Regarding socio-economic class, 64·7 % belonged to classes B2 and C1, 20·2 % to classes A1, A2 and B1, and 14·1 % to classes C2 and D.

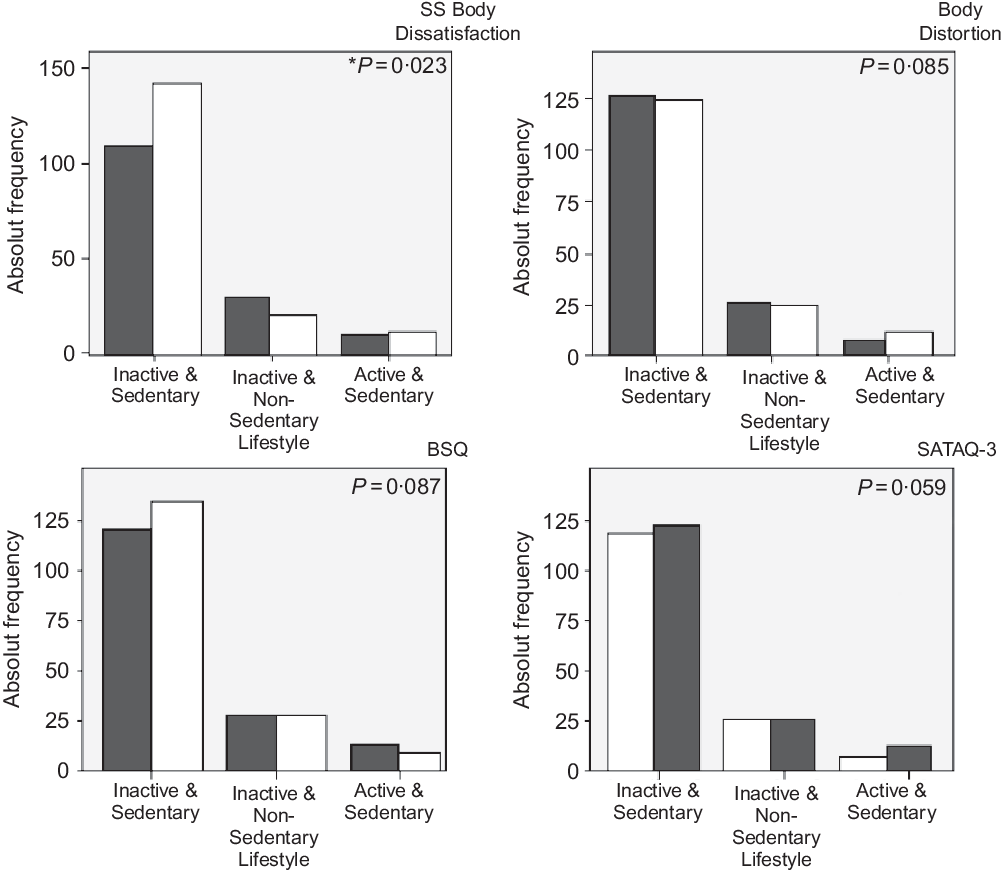

According to the lifestyle model, the girls classified as having an ‘Inactive & Sedentary’ lifestyle had 0 % of probability to reach the recommended number of steps (average of 11 700 steps), 20 % of probability to have normal ST (less than 2 h/d), and less than 50 % of probability to attain the recommendations for MVPA (minimum of 60 min), sitting time and number of meals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Profile plot of latent class analysis model of female adolescents’s lifestyle, Viçosa-MG, 2019. ρ, item-response probability; Class 1, Inactive & Sedentary Lifestyle; Class 2, Inactive & Non-Sedentary Lifestyle; Class 3, Active & Sedentary Lifestyle; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. ![]() , class 1 – γ: 0·775;

, class 1 – γ: 0·775; ![]() , class 2 – γ: 0·1631;

, class 2 – γ: 0·1631; ![]() , class 3 – γ: 0·0615 (Prevalences (γ) of latent class)

, class 3 – γ: 0·0615 (Prevalences (γ) of latent class)

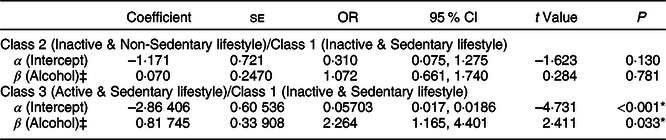

It was important to observe that the female adolescents who had ‘never consumed alcohol’ were 2·26 times as likely (log OR = 0·8174; P = 0·033) to belong to class 3 (Active & Sedentary lifestyle) than to class 1 (Inactive & Sedentary lifestyle). There was no association between class 2 and class 1 (P = 0·781) (see Table 1).

Table 1 Alcohol as a predictor of membership in latent classes of female adolescents’ lifestyle ,Viçosa-MG, Brazil, 2019†

† Logistic regression analysis output by poLCA.

‡ Never consumed.

* P < 0·05.

Also, it was verified that 82·57 % of female adolescents were classified as inactive by pedometer evaluation, and 41·55 % reported less than 60 min of MVPA per day. The sedentary behaviour was high in both situations, ST (72·90 %) and CT (65·31 %) evaluation. Approximately, 50 % of the girls reported making less than four meals a day. Regarding alcohol and tobacco use or exposition, 56·3 and 62·5 %, respectively, responded at least once to have consumed alcohol or being exposed to tobacco.

The mean BMI measured by the Silhouette Scale was similar to the mean of the actual BMI measured, 22·22 and 21·73 kg/m2, respectively. More than 75 % of the adolescents were categorised as eutrophic; however, 54·68 % had high BFP. Regarding WHtR measurement, we found that 13·6 % of the female adolescents studied presented low WHtR and 14·1 % high WHtR.

Through the body image evaluation, 51·37 % of the participants were dissatisfied with their current physical appearance and 52·87 % presented body distortion. The mean score for weight dissatisfaction was 85·14 % (±33) points by BSQ, with 47·3 % classified as dissatisfied and 7·98 % specifically as severely dissatisfied. The SATAQ-3 score indicated media influenced 51·41 % on the cognitive aspect of body image.

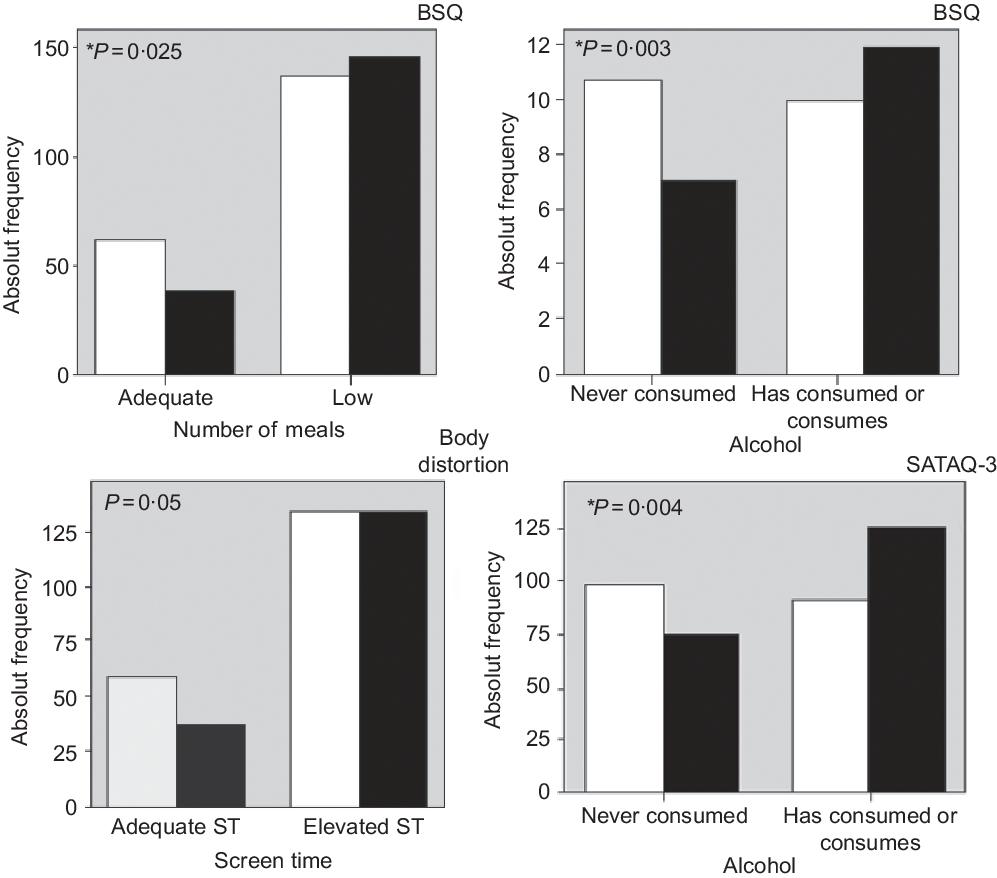

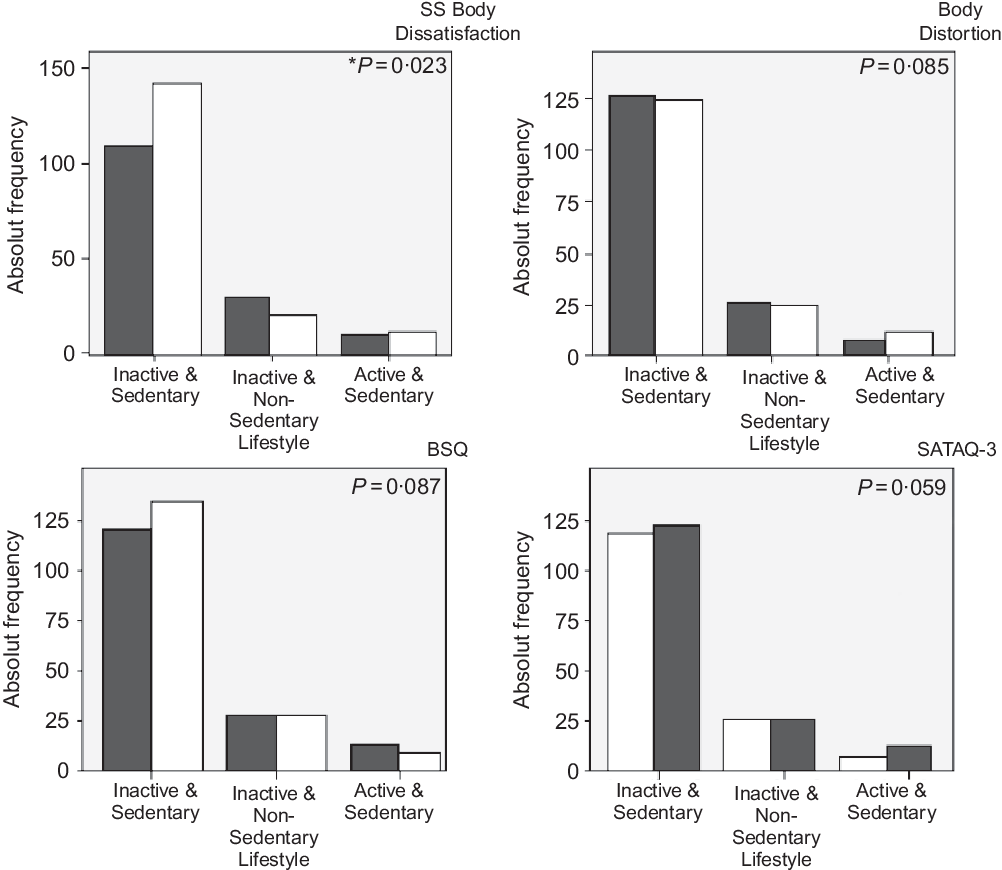

An association between the latent lifestyle classes and body dissatisfaction, as assessed by the scale of silhouettes, was found to exist (Fig. 2). Adolescents who belonged to the ‘Inactive and Sedentary’ class were more dissatisfied with their current silhouettes when compared with those in the ‘Inactive and Non-sedentary’ and ‘Active and Sedentary’ classes. This association was not observed with the other body image assessment methods. No association was found between socio-economic classification and any body image disorder.

Fig. 2 Association between body image evaluation and female adolescents’ lifestyle (Evaluated by latent class analysis), Viçosa-MG, 2019. *P-value of χ2 test < 0·05. BSQ, Body Shape Questionnaire (![]() , satisfaction;

, satisfaction; ![]() , dissatisfaction); SS, Silhouette Scale (

, dissatisfaction); SS, Silhouette Scale (![]() , satisfied;

, satisfied; ![]() , dissatisfied); SATAQ-3, Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (

, dissatisfied); SATAQ-3, Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (![]() , non-elevated;

, non-elevated; ![]() , elevated); body distortion:

, elevated); body distortion: ![]() , no body distortion;

, no body distortion; ![]() , body distortion

, body distortion

Simple logistic regression analysis associated latent lifestyle with current physical appearance dissatisfaction. Adolescent girls in the ‘Inactive & Sedentary’ class had a 1·71-fold (95 % CI 1·08, 2·90, P = 0·047) higher odds of feeling unsatisfied than adolescents from the ‘active/sedentary’ and ‘inactive/non-sedentary’.

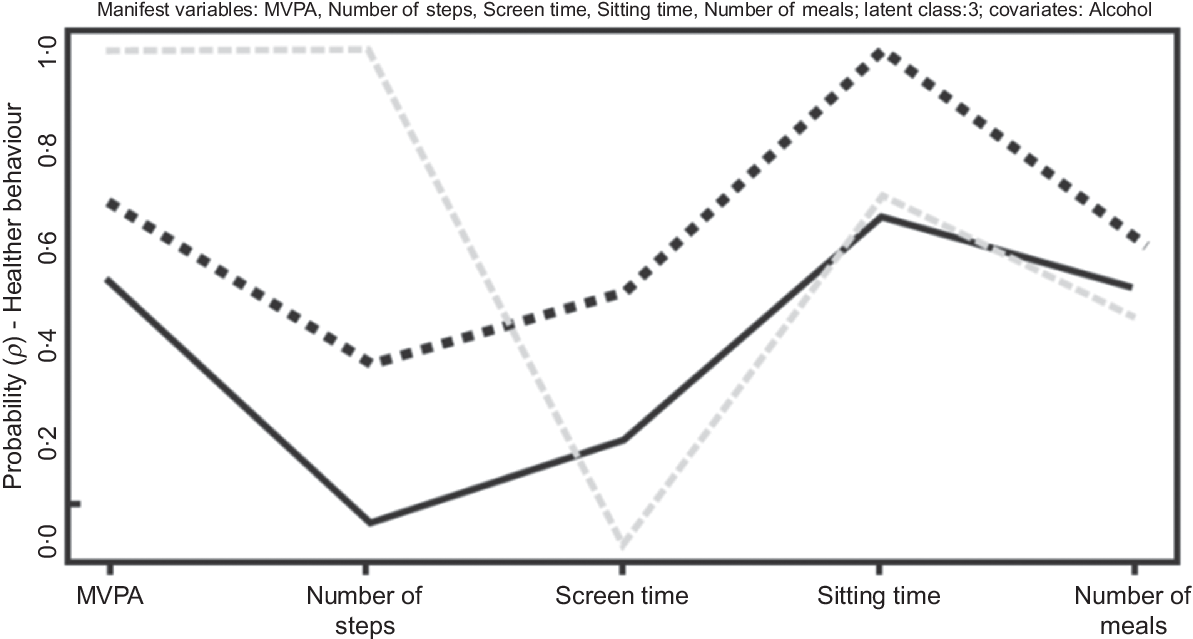

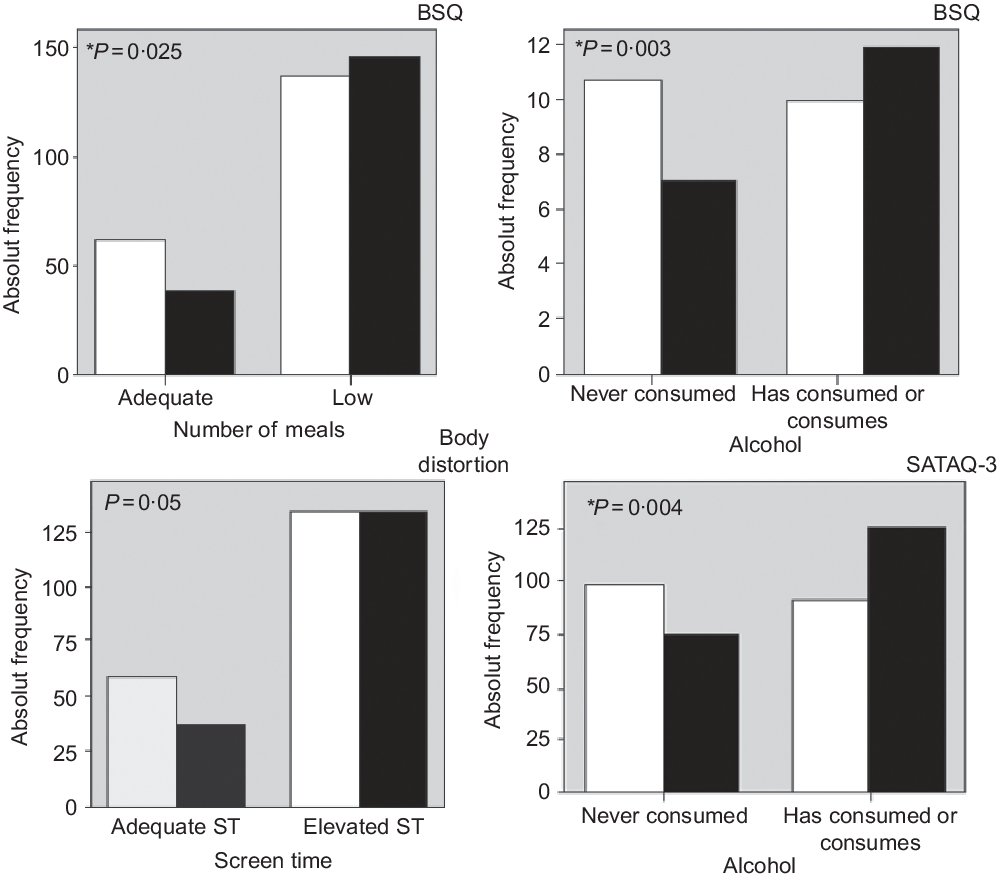

When analysing separately the measures for lifestyle evaluation, the number of meals (P < 0·05), alcohol consumption (P < 0·05) and ST (P = 0·05) were associated with different body image evaluations (Fig. 3), according to χ 2 test.

Fig. 3 Association between body image evaluation and behaviour variables of female adolescents’ lifestyle, Viçosa-MG, 2019. *P-value (<0·05) of χ2; ‡mean values ≤ 4 meals during weekdays. BSQ, Body Shape Questionnaire (![]() , satisfaction;

, satisfaction; ![]() , dissatisfaction); SATAQ-3, Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (

, dissatisfaction); SATAQ-3, Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (![]() , non-elevated;

, non-elevated; ![]() , elevated); body distortion:

, elevated); body distortion: ![]() , no body distortion;

, no body distortion; ![]() , body distortion

, body distortion

The simple logistic regression described adolescents with high WHtR (OR 5·79, 95 % CI 2·92, 11·48, P < 0·001), eutrophic with high BFP (OR 2·54, 95 % CI 1·56, 4·13, P < 0·001) and with overweight/obesity & high BFP (OR 6·5, 95 % CI 3·69, 12·69·, P < 0·001) were more dissatisfied with their current silhouette.

Adolescents with high ST (OR 1·59, 95 % CI 0·991, 2·566, P = 0·05), elevated BMI and high BFP (OR 2·80, 95 % CI 1·646, 4·768, P < 0·001) presented greater body distortion than those with adequate ST and those eutrophic with adequate BFP.

Adolescents who used to consume or still consume alcohol had a 1·80-fold (95 % CI 1·20, 2·71, P = 0·004) higher odds of having high SATAQ-3 scores, which showed greater media and socio-cultural environment influence in the cognitive aspect of body image.

Most adolescents who had few meals (OR 1·69, 95 % CI 1·06, 2·69, P = 0·026) presented alcohol consumption (OR 1·82, 95 % CI 1217, 2723, P = 0·004), high WHtR (OR 8·71, 95 % CI 2·77, 7·56 P < 0·001), eutrophic with high BFP (OR 4·58, 95 % CI 8·65, 33·072, 0·001) and adolescents with elevated BMI and high BFP (OR 16·915, 95 % CI 8·65, 33·072, P < 0·001) were dissatisfied with their body weight.

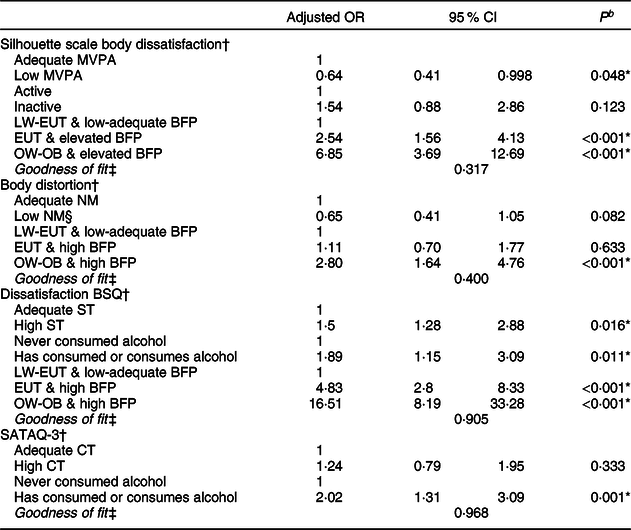

The final multiple logistic regression model of each aspect of the assessed body image is presented in Table 2. Girls who practiced MVPA adequately (above 60 min/d) with high BMI and BFP were more dissatisfied with the current silhouette. Only adolescents with high BMI and BFP showed body image distortion. Body weight dissatisfaction (BSQ) was associated with increased ST, alcohol consumption, elevated BMI and high BFP. Finally, the SATAQ-3 model identified that adolescents who consumed alcohol had negative cognitive evaluation of body image.

Table 2 Multiple logistic regression between body image evaluation, variables of lifestyle and body composition of female adolescents, Viçosa-MG, 2019

NM, number of meals; BFP, body fat percentage; BSQ, Body Shape Questionnaire; SATAQ-3, Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activities; ST, screen time; CT, cell phone time; LW, low weight; EUT, eutrophic. b: P-value of the Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis.

† Backward selection mode of variables with P ≤ 0·200.

‡ Hosmer & Lemeshow test.

§ Mean values ≤ 4 meals during weekdays.

* P < 0·05 of Wald statistic.

Discussion

Body image was related to the lifestyle of each female adolescent. Those who were most dissatisfied with their current silhouette presented inactive and sedentary lifestyle. Other factors also associated with negative body image were the number of meals, MVPA, alcohol consumption, high ST, excess weight and high percentage of body fat.

Based on the discrepancy between the perceived body shape and the ideal one, the prevalence of body dissatisfaction varies markedly among children and adolescents. Dion et al.(Reference Dion, Hains and Vachon32) analysed the body dissatisfaction of Canadian children and adolescents of both sexes. The outcomes of this study presented an interaction between sex and perceived shape, revealing that girls who perceived themselves as having a larger shape were more likely to desire a thinner shape than boys.

Researchers(Reference Lott, Kriska and Barinas-Mitchell33,Reference Iannotti and Wang34) have concluded that the assessment of lifestyle-related behaviours in a single latent variable may correlate with other outcomes regarding health conditions. The latent variable, or construct, is not observed directly, but measured indirectly through two or more manifest variables(Reference Linzer and Lewis17). Therefore, it may be considered as a more robust analysis with a higher probability of being associated with other outcomes, such as, for example, body image evaluation.

Other studies(Reference Shirasawa, Ochiai and Nanri13,Reference Añez, Fornieles-Deu and Fauquet-Ars35) have shown an association between measures of adolescent lifestyle assessment and body images. Añez et al.(Reference Añez, Fornieles-Deu and Fauquet-Ars35) found that diet, habitual PA, sedentary behaviour and elevated BMI were associated with female adolescent body image. These researchers concluded that body dissatisfaction is a barrier to regular practice of moderate and vigorous PA(Reference Añez, Fornieles-Deu and Fauquet-Ars35). The results demonstrated that girls in the active/sedentary and inactive/non-sedentary classes were more satisfied with their current physical appearance than adolescents in the ‘inactive and sedentary’.

Controversially, when measures of lifestyle assessment were analysed separately, those with high MVPA were more strongly dissatisfied with their bodies than those with low MVPA time. These results corroborate with Rech et al.(Reference Rech, Araújo and Vanat36), who report dissatisfaction with body image may be related to greater adherence and practice of PA. This last premise should be taken with caution, as several studies show body dissatisfaction as a possible barrier to regular practice of PA(Reference Lott, Kriska and Barinas-Mitchell33,Reference Kopcakova, Veselska and Geckova37) .

Sedentary behaviour was high among adolescents, approximately 60 % had ST and CT above 120 min/d, values above recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics(23). The growth in the last years in the accessibility to this technology highlights the importance of researching the relation between computer, tablet and smartphone use and body image evaluation(Reference Añez, Fornieles-Deu and Fauquet-Ars35). Thorp et al.(Reference Thorp, Owen and Neuhaus38) found that in adults, high TV and computer time is related to weight gain, obesity risk, decreased self-esteem, reduced academic performance, depression and as a potential risk factor for eating disorders. Such results are not conclusive with adolescents.

In the present study, female adolescents with high ST scores were 1·5 times (95 % CI 1·28, 2·88, P = 0·016) more likely to show body dissatisfaction than those with adequate ST scores (<2 h); the latter were also observed to show less body distortion (P = 0·05). Increased ST may represent a greater exposure to the media or social networks like Facebook, which can condition the internalisation of a lean body type, most idealised by female adolescents(Reference Golden, Schneider and Wood7). Amount of time spent on Facebook was associated with physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk, in turn, was associated with greater body image concerns(Reference Walker, Thornton and Choudhury39). Furthermore, more time spent in front of a screened device reduces the active lifestyle, in addition to conditioning the accumulation of body fat, which is one of the main factors related to increased body dissatisfaction in female adolescents.

Early attempts to lose weight by eating healthily can progress to excessive dietary restriction, prolonged periods of hunger, use of self-induced vomiting, diet pills or laxatives(Reference Golden, Schneider and Wood7). The small number of meals was observed in adolescents with body and weight dissatisfaction (Fig. 2). This shows that body dissatisfaction can condition the decrease in the number of meals, aiming at rapid weight loss and an inconsequential desire for their perceived ideal body type. According to Hyanos et al.(Reference Hyanos, Watts and Loth40), depressive symptoms and low self-esteem may be especially important targets for risk identification and prevention for disordered restrictive eating in American adolescents from public schools.

For Golden et al.(Reference Golden, Schneider and Wood7), a diet defined as energy restriction with the goal of weight loss is considered a risk factor for obesity and eating disorders. Some adolescents may misinterpret what is ‘healthy eating’ and engage in health-damaging eating behaviours such as skipping meals or using fad diets to achieve what they believe to be the optimal physical appearance, aiming at thinness(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Chen41). This is a critical issue that should be better investigated by health researchers.

In addition to small number of meals, alcohol and tobacco consumption were observed in adolescents and related to the negative evaluation of body image. The most dissatisfied with weight and with negative cognitive evaluation of body image reported having consumed or consumed alcohol (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The interrelationship between alcohol, tobacco and marijuana with body image disorders is not well discussed or documented today among adolescents(Reference Gutiérrez, Espinoza and Penelo42). Nevertheless, a relationship between these harmful substances and body image is hypothesised because they can interfere in the neurological system, which is a body image component. Adults and adolescents with symptoms of eating disorders tend to show higher consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs than healthy people(Reference Iannotti and Wang34). Gutiérrez et al.(Reference Gutiérrez, Espinoza and Penelo42) found a positive association between consumption of alcoholic beverages and tobacco with risky eating behaviour in adolescents of both sexes of Barcelona, Spain.

The measurements of body composition were associated with negative body image evaluation. Adolescents with elevated BMI and high BFP were more likely to report body image distortion and dissatisfaction compared to girls with adequate BMI and BFP. Body image is directly related to elevated BMI(Reference Farhat12). In the present study, the excess body fat was associated with the negative body image assessment of female adolescents.

This is a worrying fact because fat has a significant role during adolescence. In addition to contributing to the sexual development, the menarche and the consolidation of the body structure, especially the bone, fat is present in hormone. The excessive concern with the percentage of body fat, along with media influence imparting the perception of ‘perfect body’, can stimulate adolescents to adopt unhealthy nutritional strategies in conjunction with dysfunctional physical exercises during the transition from adolescence to adulthood(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Chen41).

Adolescents with elevated BMI or who perceive themselves as such have more difficulty reaching an idealised lean body, thus creating a constant internal state of stress(Reference Griffiths, Murray and Bentley2). The negative assessment of body image is associated with multiple health risk behaviours(Reference Golden, Schneider and Wood7,Reference Gualdi-Russo, Rinaldo and Khyatti43) , including mental health problems (depression, low self-esteem), health problems reported by the person, consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs, increased sedentary behaviour and poor dietary choices (unhealthy diet, poor dietary intake)(Reference Iannotti and Wang34).

Stigma arising from excessive weight and the perception of an elevated BMI can be considered triggers for increased production of stress hormones, such as cortisol(Reference Farhat12). This hormone helps store fat and increases appetite, factors associated with weight gain. The more the individual is exposed to stress due to obesity, the higher the cortisol production, consequently increasing the manifestation of factors associated with elevated BMI(Reference Farhat12).

The results presented in this study highlight the importance of associating different types of body image disorders and behavioural aspects of adolescents. Innovative approaches are necessary for adolescents to construe beliefs about fat and develop criticism towards the media influence on their quality of life. For example, mindful and intuitive exercise are activities that involve listening the body while moving and incorporating the senses(Reference Reel44). The true intention of the intuitive exercise is to make the PA practically more enjoyable rather than simply a means to lose or control weight, and it is likely to become a sustainable habit(Reference Philippi and Leme45).

It is of the utmost relevance to present and discuss the health consequences arising from inappropriate behaviour in the short, medium and long term. In short, teenagers must be educated about how emotion and mind care benefit health and prevent symptoms of many psychiatric disorders such as depression, eating disorders, dependence on alcohol and drugs, and suicide. These are serious diseases requiring long and highly qualified treatment.

The present study, in turn, was an original and pioneering endeavour evaluating different body image disorders, body composition and LCA with covariates in the assessment of lifestyle, from the observation and interaction of behaviours adopted by Brazilian female adolescents.

A limiting aspect of this research was the subjective nature of the method employed to analyse sedentary behaviour. However, a previous study has shown the self-reported ST can be a reliable tool for evaluating the sedentary behaviour(Reference Miranda, Amorim and Bastos16). Furthermore, together with pedometer measurements, the ST for different devices, such as TV, computers, video games, tablets and cell phones, was measured. The 7-d evaluation was important to allow greater investigation and control of the habitual behaviours of the adolescents.

It is also important to consider the effects of weight-teasing in body dissatisfaction. In Brazil, there is an evidence supporting that unhealthy weight control practices were significantly associated with body dissatisfaction in 253 female adolescents from public schools. A high proportion of adolescents reported weight-teasing by their family and peers, suggesting that the ideal internalisation regarding appearance during adolescent potentially can also contribute to the development of obesity and eating disorders(Reference Leme, Philippi and Thompson46).

The relevance of the study was to evaluate the relationship between lifestyle, analysed through LCA, with distinct aspects of body image – dissatisfaction with the current silhouette, body distortion, weight dissatisfaction (BSQ) and cognitive evaluation of body image (SATAQ-3). According to Laus et al.(Reference Laus, Almeida and Murarole29), in addition to body dissatisfaction, other aspects of body image are not commonly investigated among adolescents. Another relevant aspect was the evaluation of the body composition in a joint way between BMI and the percentage of body fat by Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry, which is considered a reference method(Reference Farhat12). We could identify whether the eutrophic adolescents had adequate or high BFP, determinant factors in the association with body image.

Several researches show that excess weight, especially body fat, can trigger stress caused by negative body image evaluation, and in turn, inhibit the adoption of regular PA and decrease sedentary behaviour(Reference Farhat12,Reference Corder, Ekelund and Steele19,Reference Alvarenga, Dunker and Philippi31,Reference Añez, Fornieles-Deu and Fauquet-Ars35,Reference Hyanos, Watts and Loth40,Reference Gutiérrez, Espinoza and Penelo42) . Hence, the importance of concomitant assessment of lifestyle measures and different methods for assessing body composition. An yet to contribute positively to the physical, cognitive and psychosocial development of adolescents.

Conclusion

Adolescents classified by LCA as Inactive and Sedentary lifestyle were more dissatisfied with their current physical appearance in relation to the Active and Inactive and Inactive and Non-sedentary lifestyle. Female adolescents who had ‘never consumed alcohol’ were more likely to belong to the Active and Sedentary lifestyle class than to the ‘Inactive and Sedentary lifestyle class. Additionally, the low number of meals, adequate MVPA (analysed separately from sedentary behaviour), alcohol consumption, high ST scores, excess weight and a high percentage of body fat were related to body distortion, weight dissatisfaction and negative cognitive evaluation of body image.

Studies that evaluate different measures of lifestyle and body composition in further detail are needed for the elaboration of more effective interventions seeking to minimise deleterious manifestations of body image disturbances. Health risk behaviours developed in the pursuit of an idealised physical appearance should be detected early and addressed properly lest they be allowed to jeopardise the physical, psychic and social development of adolescents.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in the study and the teachers, educators and principals who facilitated this research to take place. Financial support: This work was supported by the Foundation Support Research of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) - 01/2014, process: APQ-02584-14 and National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) - Nº 14/2014, Process: 445276/2014-2.). Conflict of interest: All authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Authorship: V.P.N.M. conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript. P.R.S.A. designed the study, performed the measurement and final approval of the manuscript. R.R.B. performed statistical analysis, interpretation of the data and final approval of the manuscript. V.G.B.S. performed statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. E.R.F. participated in the design and helped to draft the manuscript. S.C.C.F. conceived the study, participated in its design and final correction. P.C.T. performed drafting and reviewing of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. S.E.P. conceived the study, participated in its design, coordination and final approval of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was approved by the Federal University of Viçosa’s Committee for Ethics in Research with Human Beings, having been filed on the Brazil Platform under the number 30752114.0.0000.5153, decision 700.976/2014. The present project followed the rules set forth by Brazilian National Health Council Resolution 466/12. Each volunteer only took part in the project after turning in the Assent Form and the Informed Consent Form, signed respectively by herself and by her parents or legal guardians. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.