The landscape of dairy and plant-based dairy alternative (PBDA) product consumption is changing. While consumption of total dairy remained consistent between 2004 and 2015 among Canadian adults and children, consumption of fluid cows’ milk decreased, whereas consumption of other dairy products, such as cheese and yogurt, increased(Reference Tugault-Lafleur and Black1). At the same time, the availability and consumption of PBDA have steadily increased in recent years, currently making up 7·4 % of the total milk market share and expected to reach 18·5 % by 2023(Reference Schiano2). Although little research has been conducted on the prevalence of PBDA intake in Canadian children, a previous analysis of families of preschool-age children conducted by our research team showed that while almost all families purchased cheese/yogurt or cows’ milk, 35 % also purchased PBDA(Reference Laila, Darlington and Duncan3), suggesting that approximately 35 % of families provide both dairy and PBDA. This trend by Canadian families to purchase complementary PBDA products in addition to or to replace dairy products precipitated the need to investigate the determining motivations for this phenomenon, as the nutritional profiles of dairy and PBDA can vary greatly.

Dairy products, which are the products made from the milk of mammals, typically cows, sheep and goats, are an excellent source of Ca, vitamin D and protein(Reference Rangan, Flood and Denyer4). In children and adolescents, intake of dairy products is positively associated with meeting growth and development milestones(Reference Dror and Allen5). However, an analysis of 2012/2013 data showed that 32 % of Canadian children and adolescents are vitamin D deficient; this percentage represents an increase from 21 % in 2008–2009 and was associated with a decrease in milk and fish consumption(Reference Munasinghe, Willows and Yuan6). Low intakes of Ca and/or vitamin D, resulting from low intake of dairy products, have been proposed as possible factors driving several associations with health implications, including poor bone health(Reference Auclair, Han and Burgos7) and a higher risk of developing hypertension(Reference Rizzoli8), obesity(Reference Nicklas, Qu and Hughes9,Reference Tremblay and Gilbert10) , type 2 diabetes(Reference Rizzoli8,Reference Wang, Troy and Rogers11) and colorectal cancer later in life(Reference O’Connor, Lentjes and Luben12).

Alternatively, PBDA are typically made from nuts, grains or legumes, with soya, almond, rice and coconut beverages being the most widely produced alternative milk products around the world(Reference Vanga and Raghavan13). The contribution of PBDA products to nutritional status varies. Some products, such as soya-based beverages, provide an equivalent amount of Ca and vitamin D as cows’ milk(Reference Vanga and Raghavan13). However, compared with cows’ milk, many PBDA, especially rice and coconut beverages, contribute less Ca and protein and more sugar to the diet(Reference Vanga and Raghavan13). While no research has investigated the associations of inadequate PBDA intake in childhood with health outcomes, nutritionally adequate PBDA products can contribute to protein intake and vitamin D and Ca status and thus should be considered an important aspect of the diet, especially if replacing dairy products. Ensuring quantitative and qualitative adequacy of dairy and PBDA intakes, therefore, is a public health priority.

This priority is especially important for children given that dietary habits, such as cows’ milk consumption, established in childhood can persist into adulthood(Reference Grimm, Harnack and Story14,Reference Couch, Glanz and Zhou15) . It is well established that parents can influence their children’s nutritional intake through parental feeding behaviours and by modelling dietary behaviours(Reference Hanson, Neumark-Sztainer and Eisenberg16–Reference Faith, Scanlon and Birch18). Parents’ feeding practices and their own dietary intake of dairy and PBDA are influenced by their perceptions of these products. Thus, the aim of this study is to explore barriers and facilitators of the provision of dairy and PBDA by parents of preschool-age children. Results of this research can provide insight into parents’ decision-making when choosing to provide dairy and/or PBDA to their preschool-age children and can aid in the development of appropriate educational tools and behaviour interventions to ensure the consumption of nutritionally adequate products.

Methods

Recruitment

This sub-study was conducted at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, as part of two larger studies. The first is the Guelph Family Health Study, a long-term study that investigates lifestyle behaviours, including nutrition and physical activity, of families with preschool-age children. The second is the Family Food Skills Study, which sought to gain a better understanding of meal preparation, and food purchasing and consumption in families with young children. Both studies took place in Guelph, Ontario, Canada. Eligible participants for this focus group study from these two larger studies were parents of preschool-age children (18 months–5 years) living in and around Guelph and who could comfortably communicate in English. Demographic information about participants and their households was extracted from surveys from the two larger studies. Participants were recruited from these two studies as a convenience sample.

In February 2019, eligible participants were invited to participate through an email sent to parents enrolled in either the Guelph Family Health Study, which had 106 participants, or the Family Food Skills Study, which had eighty-five participants. Interested participants were sent consent forms via email prior to the focus group and provided informed consent before participation.

Participants and focus groups

Five focus groups of five to eight participants per group were conducted in March and April 2019 by two trained facilitators (A.L. and N.T.). A total of thirty-two parents (thirteen fathers, nineteen mothers) of at least one preschool-age child from twenty-four households participated (see Table 1). Of the thirty-two parents, twenty-five were participants in the Guelph Family Health Study and seven were participants in the Family Food Skills Study. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 min and followed a semi-structured interview guide developed using Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour(Reference Bandura and Locke19,Reference Ajzen20) . These theories aimed to describe underlying constructs for behaviour patterns, such as attitude, perceived behaviour control, self-efficacy, social outcome expectations and subjective norms. These two theories have been used previously in qualitative research exploring dairy and PBDA perceptions(Reference Racey, Bransfield and Capello21,Reference Lacroix, Desroches and Turcotte22) . Interview guide questions were created to explore barriers and facilitators to household provision and children’s consumption of dairy and PBDA, including reasons for offering/not offering, purchasing habits and sources of information. The semi-structured interview guide can be found in online Supplementary Material. Three researchers were present during each focus group (moderator, assistant and notetaker). Sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim (http://wreally.com/).

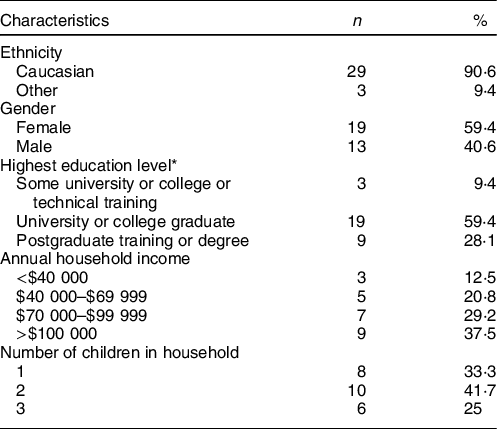

Table 1 Demographics of focus group participants (n 32) and their households (n 24), Guelph, Ontario, March–April 2019

* One household did not provide an answer.

Qualitative analysis

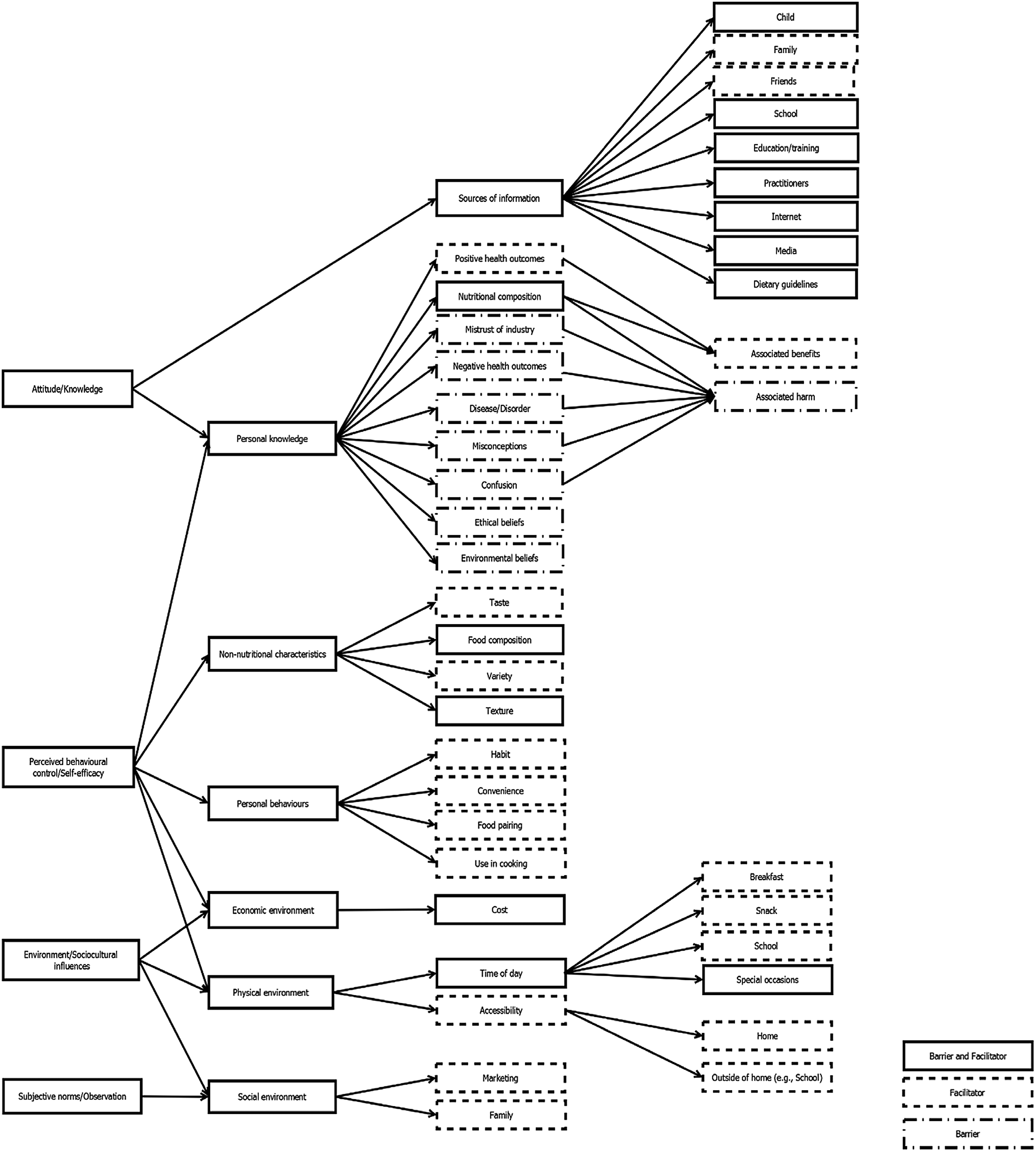

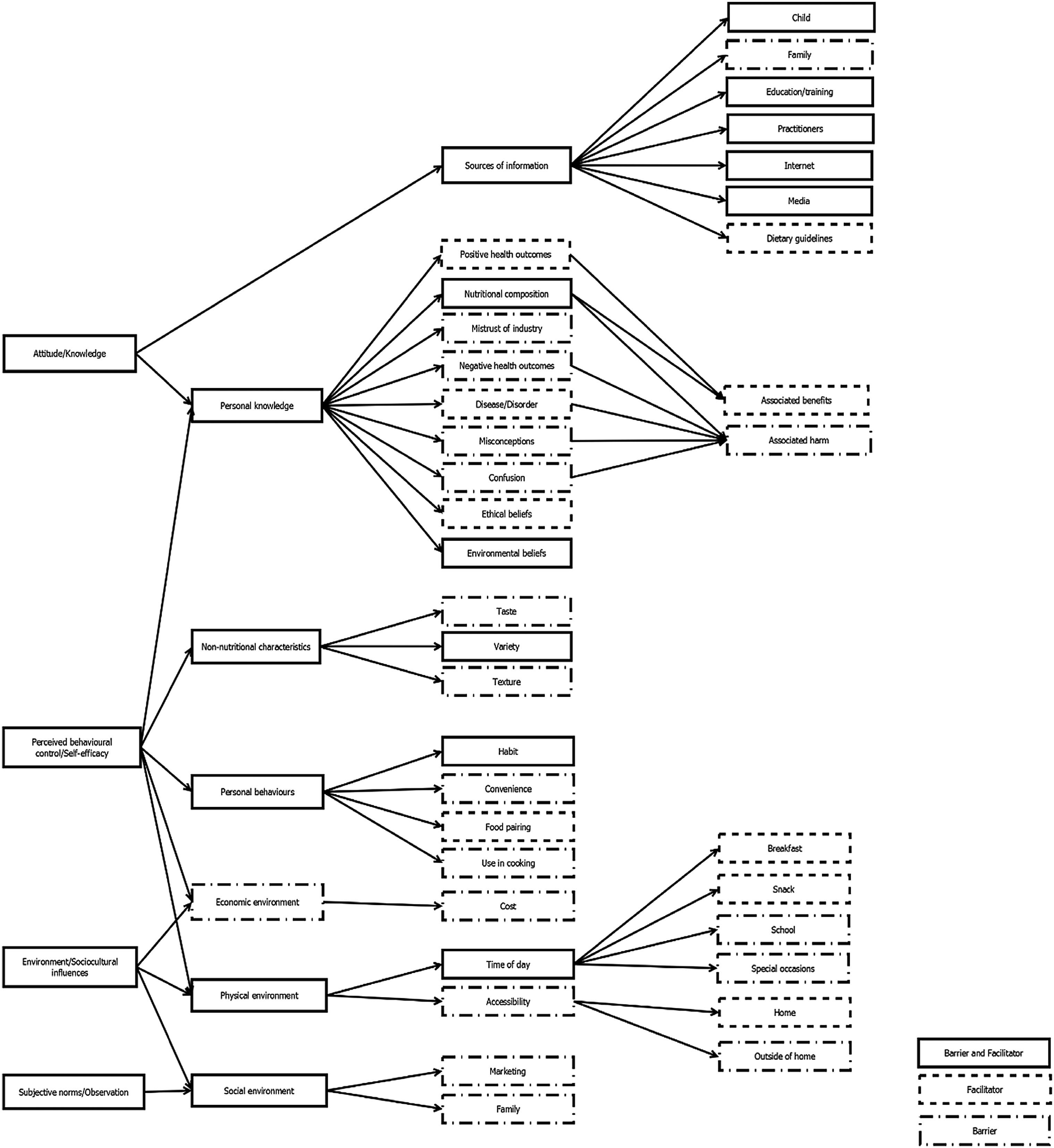

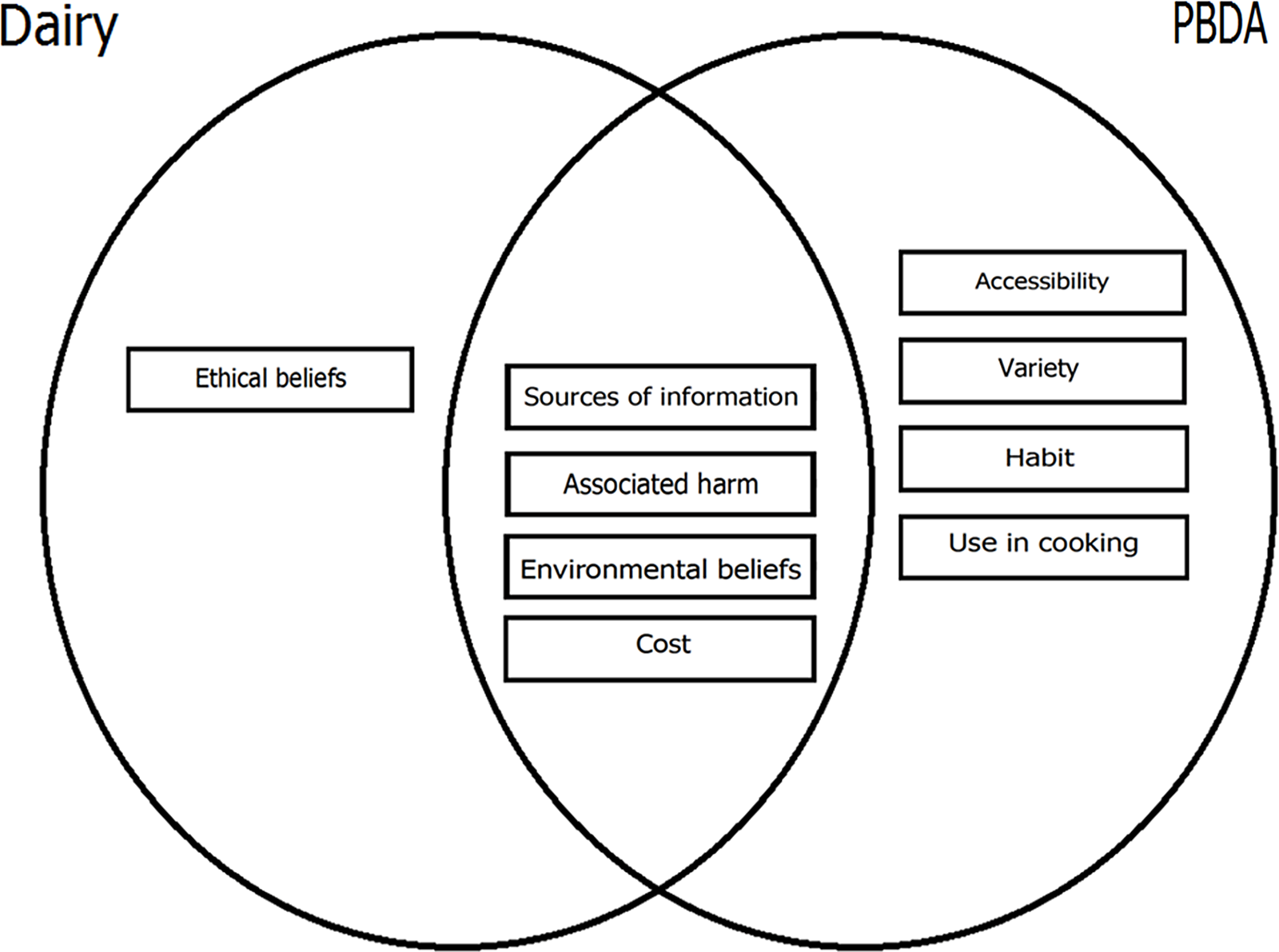

Transcribed data were analysed using Nvivo 12 qualitative analysis software (QSR International, 2019). Thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clark(Reference Braun and Clarke23), was used to systematically classify and identify major themes from the data set. Two researchers (A.L. and N.T.) coded the data separately and then compared coded data to ensure accuracy and to identify common themes. Coded data were grouped into common themes; initial themes were reviewed and edited (e.g. renamed or collapsed) until each theme described a unique aspect of the data. Once initial salient themes were identified, the researchers then examined the data through the theoretical context of Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Figs. 1 and 2). Discrepancies between theme and subtheme identification were resolved through discussion and consultation with two additional researchers (A.C.B. and G.N.) if needed.

Fig. 1 Theory-grounded representation of barriers and facilitators to the provision of dairy in households with preschool-age children

Fig. 2 Theory-grounded representation of barriers and facilitators of the provision of plant-based dairy alternatives in households with preschool-age children

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of thirty-two parents (nineteen mothers, thirteen fathers) from twenty-four households participated in the focus groups. A majority of participants were Caucasian (90·6 %), had higher education levels (undergraduate or college degree and above, 87·5 %), and had an annual household income of $70 000 or more (66·7 %) (see Table 1).

Barriers and facilitators to intake of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives

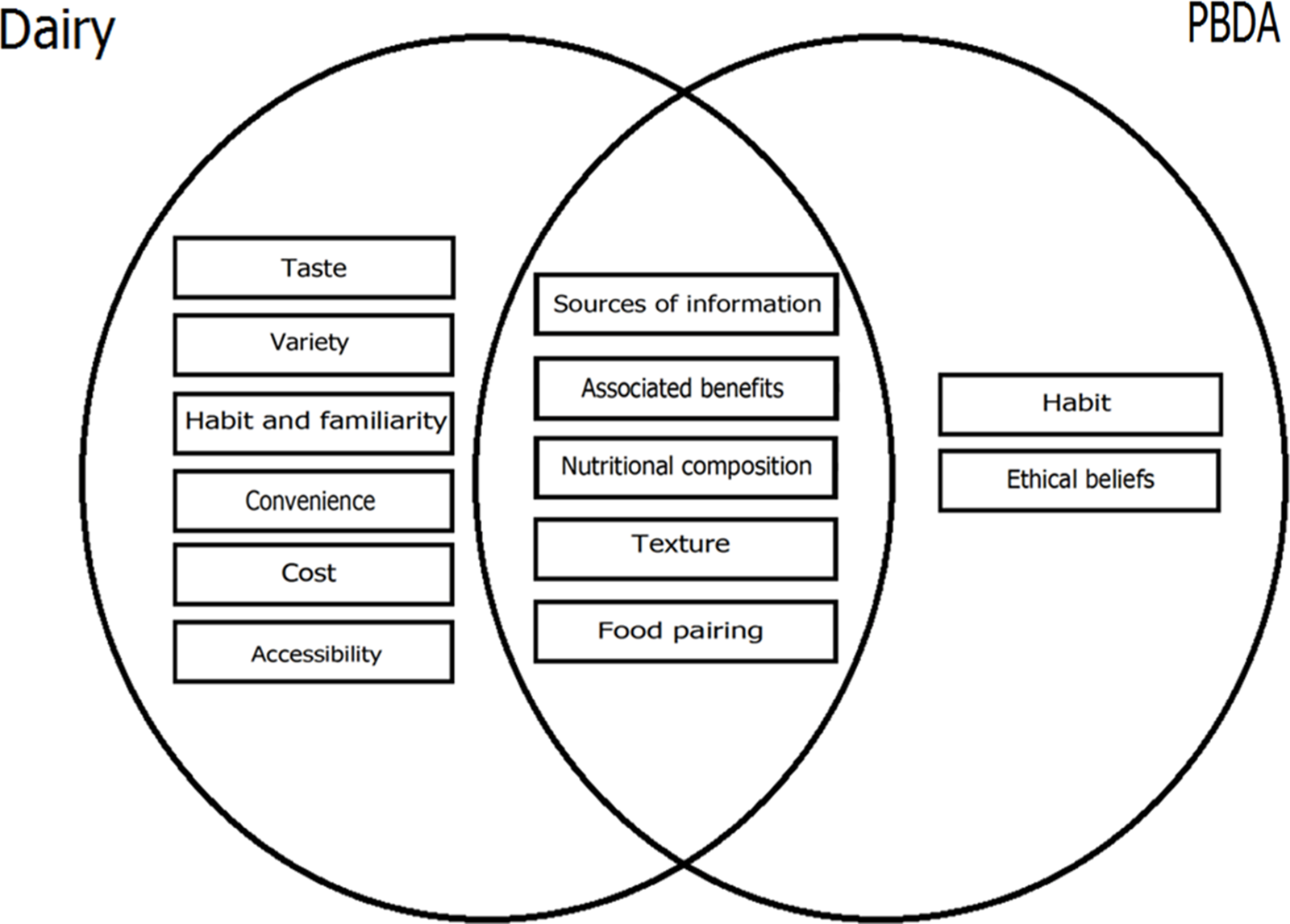

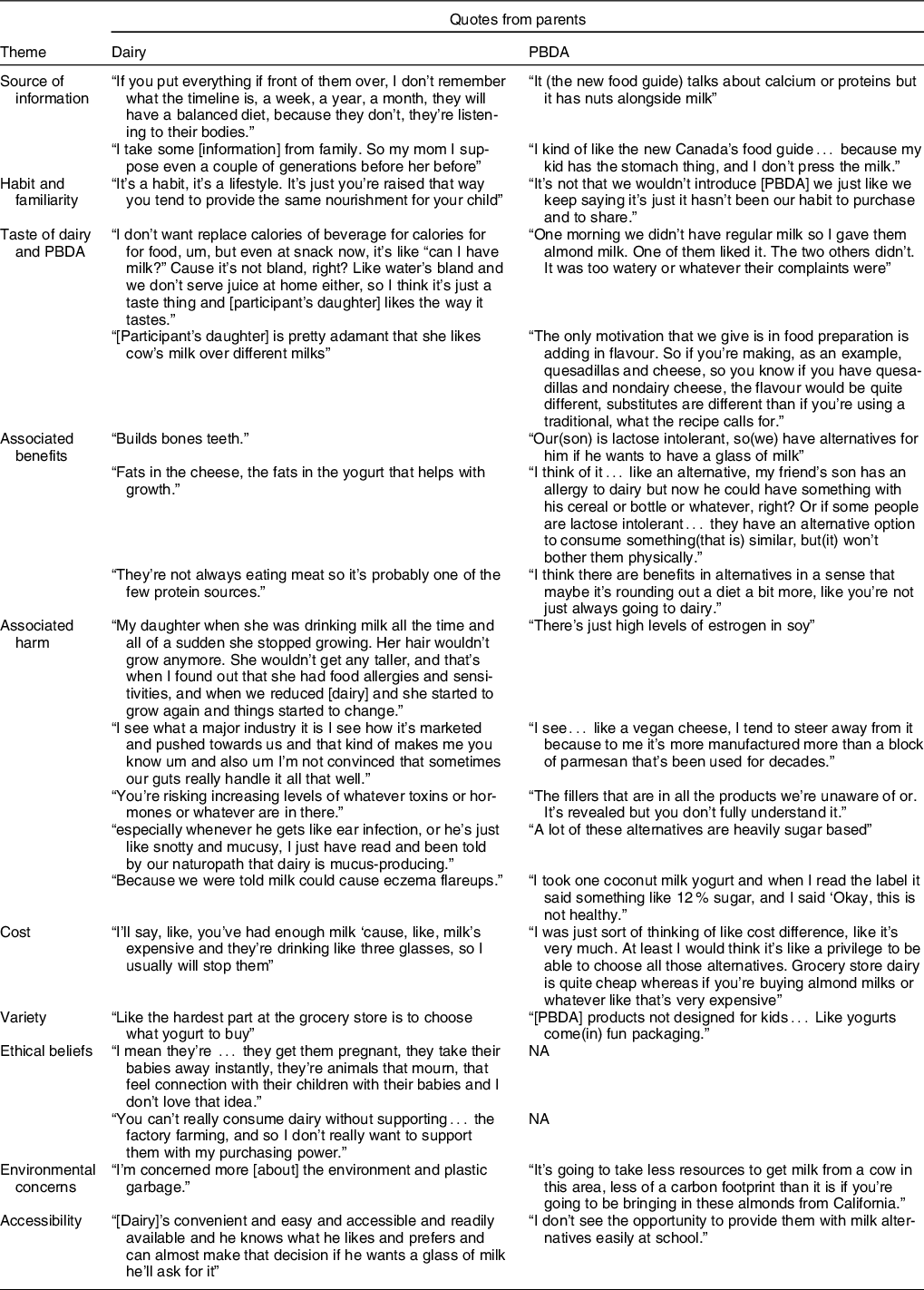

Figures 3 and 4 show a Venn diagram of facilitators and barriers of the provision of dairy and PBDA. Figures 1 and 2 are Social Cognitive Theory- and Theory of Planned Behaviour-grounded flow charts of barriers and facilitators of dairy and PBDA, and Table 2 shows selected quotes for the identified subthemes. Figures 1 and 2 show all of the barriers and facilitators to dairy and PBDA intake, as identified by thematic analysis of the transcripts and grounded in both Social Cognitive Theory and Theory of Planned Behaviour constructs. What follows is a description of the barriers and facilitators to the provision of dairy and PBDA that were common across focus groups.

Fig. 3 Venn diagram representation of facilitators to household provision of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives (PBDA)

Fig. 4 Venn diagram representation of barriers to household provision of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives (PBDA)

Table 2 Examples of quotes illustrating barriers and facilitators to dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives (PBDA) in households of preschool-age children, Guelph, Ontario, 2019

NA, not applicable.

Sources of information

Parents identified several sources of information, including health practitioners, family, friends, media and the internet. In general, nutrition information from dietitians and naturopaths was considered more trustworthy than that from doctors. Multiple sources of information, including the internet, were differentially perceived as barriers or facilitators, depending on whether dairy or PBDA was being discussed. For example, the 2019 Canada’s Food Guide(24), which combined dairy foods and meats together to form a protein foods category, was identified as a barrier to dairy provision and a facilitator to PBDA. However, this was not true for all participants; some parents either lacked knowledge about the changes in the Food Guide or were uninterested in or sceptical about the changes. Family (i.e. grandparents) was seen as a traditional source of information providing pro-dairy information and encouraging parents to provide dairy to their children. However, participants identified prioritising feedback from their children (especially regarding any gastrointestinal discomfort due to dairy) over these several sources of information.

Habit and familiarity

When asked about the reasons for offering dairy, most parents cited habit and familiarity. Parents also stated that they maintain dairy availability in the household because they grew up in a household that did the same. Therefore, habit was identified as a facilitator to providing dairy. Conversely, parents who reported providing PBDA out of habit reported doing so because of the belief that PBDA are healthy products or out of need for a replacement to dairy products. In addition, parents who reported not providing PBDA said that they were much more familiar with dairy products than PBDA, and so even if they wanted to provide PBDA, they would not possess the knowledge to do so.

Taste of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives

Many parents cited their children liking the taste of dairy products as a facilitator to household provision of dairy products. Parents believed that it was more convenient to provide preschool-age children dairy, a perceived healthful and tasty food. Conversely, taste was most often identified as a barrier to PBDA consumption of preschool-age children even though some parents reported enjoying the taste of certain PBDA products. Parents who reported providing PBDA to their children also said they would have to ‘sneak’ these products into a smoothie or a cooked item. Generally, parents agreed that their children preferred the taste of dairy products over PBDA.

Associated benefits

Parents identified several benefits of both dairy and PBDA. Benefits of dairy related to growth and bone health and were attributed specifically to the Ca, protein and fat content. In fact, several parents said they purchase dairy products with higher fat contents (full-fat milk, higher fat yogurt) for their young children because they valued fat and its necessity in brain development. Another nutritional facilitator was the protein content of both dairy and PBDA, which was perceived to support growth. In addition to protein, the vitamin and minerals in PBDA were perceived to support children’s nutrition. Besides supporting growth, a small number of parents who reported providing PBDA mentioned the fibre content of PBDA, providing diversity to the diet, or general perceived healthfulness of these products. Other parents identified the ability of PBDA to replace dairy, for those who cannot consume dairy due to milk allergies or lactose intolerance, as its only benefit.

Associated risks

Parents expressed some health concerns from consuming dairy and PBDA. Gastrointestinal issues associated with dairy such as lactose intolerance, upset stomach, constipation and diarrhoea, as well as milk allergies and skin conditions like eczema, were noted as barriers to the provision of dairy and facilitators to providing PBDA. In fact, while some parents identified as having no personal experience providing PBDA to their children, they recognised the need for PBDA as a replacement for dairy, specifically for people with conditions that prevent dairy consumption, such as lactose intolerance. In addition, a small number of parents mentioned additional perceived health risks, such as excessive mucus production and risk of autism, associated with dairy consumption.

Parents also discussed unwanted and/or unknown components of dairy and PBDA as barriers to provision of both products. Many expressed concerns over the perceived presence of antibiotics and hormones in dairy, the latter which parents believed may negatively affect growth of their child. Specific to PBDA, many parents expressed concerns over soya-based beverages and possible oestrogenic effects or perceived pesticide content in PBDA. The inclusion of ‘chemicals’ and a greater number of ingredients in PBDA were also a concern, but parents were less clear about how these might impact their child. Parents also expressed concern about ‘overly-processed’ dairy and PBDA products. While more parents said PBDA were ‘unnatural’ or ‘more processed’ compared with dairy milk, certain dairy products, such as string cheese, were also perceived as ‘processed.’

Similarly, sugar content was also a concern. Dairy products, such as chocolate milk and yogurt drinks, were identified as having high amounts of sugar; some parents even reported mixing chocolate milk with regular milk to decrease the sugar content before providing chocolate milk to their children. On the other hand, for parents who identified themselves as PBDA providers, sugar was a primary concern for PBDA and they indicated that they specifically purchase unsweetened PBDA. Because of these perceptions, including ones identified under ‘Associated Benefits,’ food composition was both a barrier and facilitator for both dairy and PBDA.

Cost

A consistent barrier for household provision of dairy and PBDA across focus groups was cost. Parents in all focus groups said the cost of PBDA was high, especially relative to dairy products, although cost of dairy was nonetheless a concern. This concern about cost of dairy was especially salient for parents who perceived their children to consume a lot of dairy, which prompted parents to exert more control over their children’s dairy intake.

Variety

The variety of PBDA was perceived variably by parents and therefore was both a barrier and a facilitator. Specifically, parents who perceived there to be a large variety of PBDA commented on the increase in selection of PBDA in recent years. Conversely, parents who perceived there to be little variety of PBDA compared the variety of PBDA with that of dairy products, especially those dairy products marketed towards children and which served as a facilitator to offering dairy to their child.

Accessibility

Several parents cited the ease of access to dairy products in grocery stores and at preschools. Compared with dairy, PBDA were perceived to be much less accessible. Some parents said finding PBDA in grocery stores was more difficult than finding dairy, and other parents complained about not being able to provide nut-based products schools or daycare. Therefore, accessibility was a facilitator to dairy provision but a barrier to PBDA.

Ethical and environmental beliefs

Ethical concerns regarding dairy farming were identified as a barrier to dairy consumption. Several parents expressed their disagreement with dairy farming practices and their openness to reducing dairy consumption or purchasing organic and/or local milk. This desire stemmed from the perception that local and organic dairy farms were more ethical. These ethical concerns over dairy farming were held even by parents who reported providing dairy.

While this ethical concern was unique to dairy, several parents were concerned about the environmental effects of both the dairy and PBDA industries. Some parents identified the carbon footprint of dairy farming and plastic waste from processed dairy products, such as yogurt tubes, as barriers to dairy. In addition, the perceived high-water usage in the processing of PBDA and the carbon footprint of importing these products were identified as barriers of PBDA. Therefore, ethical concerns over dairy farming were a barrier to the provision of dairy, but environmental concerns were a barrier to providing both dairy and PBDA.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore barriers and facilitators of both dairy and PBDA among parents of preschoolers. The findings suggest that parents of preschool-age children perceived some facilitators and barriers to be common between dairy and PBDA, whereas other facilitator and barriers differed. This concurrent exploration of facilitators and barriers of provision of both products is useful to inform our understanding of parent perceptions and behaviour. This understanding is especially important considering parents’ influence on establishing healthy eating habits in their preschool-age children in addition to ensuring adequate Ca and vitamin D intake.

Some facilitators, such as perception of associated benefits, were shared between dairy and PBDA. Previous focus group studies of adults and children have also reported that the perception of associated benefits, such as growth and bone health, was a facilitator to dairy intake(Reference Racey, Bransfield and Capello21,Reference Lacroix, Desroches and Turcotte22,Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25) . This study extends this observation and shows that while the benefit from dairy is perceived by parents to relate to its fat, Ca and protein content, the benefit from PBDA is perceived to relate to its protein, vitamin and mineral content. This study also found that a small number of parents perceived that PBDA add variety to the diet or are simply healthful. Additionally, in cases of lactose intolerance or dairy allergy, parents expressed that PBDA can be used as a replacement for dairy. Some of these findings have previously been reported. A survey study in adults found that consumers of both dairy and PBDA value the protein content of the product they reported to consume(Reference McCarthy, Parker and Ameerally26), and a focus group study with children and parents showed that variety in the diet is perceived as healthful(Reference Rawlins, Baker and Maynard27). Therefore, while a common facilitator between dairy and PBDA was perception of health benefit, each type of product was perceived to benefit health differently and uniquely.

Perception of associated risk was a common barrier to both dairy and PBDA. Similar to perception of associated benefits, the perceived risks associated with dairy and PBDA were unique. The risk from dairy stemmed from its perceived antibiotic and hormone content, consistent with previous studies on dairy(Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25,Reference Mobley, Jensen and Maulding28) . Other perceived risks of dairy included some misconceptions, such as dairy intake being associated with autism and mucus accumulation. This study extends these results to PBDA and reports that the risk from PBDA was perceived to stem from perceived oestrogenic effect of soya, pesticide residue, ‘excessive’ processing and unknown chemical ingredients; the latter two being associated with ‘unnaturalness.’ While no other study on PBDA has reported this perception of risk, previous studies on perceptions towards food have shown that consumers who fear the risk of chemical additives in food are more likely to consume products they consider more ‘natural’(Reference Dickson-Spillmann, Siegrist and Keller29). Therefore, unique associated risks of dairy consumption included risk of consuming residues of antibiotics and hormones, while unique associated risks of PBDA consumption related to perceived oestrogenic effect, pesticide residue and perception of unnaturalness.

Similarly, parents in this study were also highly concerned with the perceived sugar content of dairy products and added sugar or sweeteners in PBDA. Jung et al. (Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25) and Mobley et al. (Reference Mobley, Jensen and Maulding28) found similar perceptions towards dairy among parents of school-age children and older women, respectively, and McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Parker and Ameerally26) found that adult participants prefer PBDA with no added sweeteners. A review by the American Heart Association found that greater intake of added sugar in children is associated with an increased risk of developing CVD in childhood and that this association was mediated by increased energy intake, adiposity and dyslipidaemia(Reference Vos, Kaar and Welsh30). In 2015, the Canadian average total sugar intake of children aged 2–8 years was 101 g/d, most of which was from sugary beverages, such as soft drinks and fruit juice, but also included sugar-sweetened milk and PBDA(Reference Langlois, Garriguet and Gonzalez31). It is our recommendation that public awareness of the sugar content of selected dairy and PBDA should be increased.

Not all facilitators were shared by dairy and PBDA. The present study found specific, unique facilitators to the provision of dairy over PBDA, such as taste, habit, familiarity and availability of child-friendly products. Previous studies on dairy in older women and in parents of school-age children have reported that liking the taste of dairy and habitual intake of dairy are facilitators of intake(Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25,Reference Mobley, Jensen and Maulding28) , while lack of habitual provision of dairy is a barrier(Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25). The study by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Parker and Ameerally26) also identified taste as a main factor influencing consumer choice of PBDA. Regarding child-friendly products, dairy products featuring characters (e.g. Paw Patrol™ yogurts) were cited as preferred choices for preschool-age children across focus groups. Sonntag et al. (Reference Sonntag, Schneider and Mdege32) reported that children influence parents’ purchasing decisions by requesting products that appeal to them. Parents of preschoolers, therefore, may prefer dairy over PBDA due to preferring the taste and greater familiarity, and due to a perceived lack of child-friendly PBDA products. These latter two facilitators were cited by parents when comparing dairy to PBDA, which could explain why previous studies investigating only dairy did not report them. This highlights the importance of investigating perceptions towards dairy and PBDA concurrently.

The importance of considering dairy and PBDA concurrently can be reinforced by this study’s finding that ethical beliefs were perceived to influence the provision of dairy and PBDA products, albeit differently. Ethical concerns over dairy production were cited as a barrier to dairy provision and therefore as a facilitator to PBDA. Specifically, several parents cited the treatment of dairy cows as a motivating factor to provide PBDA to their children. Treatment of cows has been identified in previous literature as a reason for choosing PBDA(Reference McCarthy, Parker and Ameerally26), consistent with this study’s findings. Interestingly, while some parents voiced dissatisfaction with the ethics of dairy production, several admitted to nonetheless providing dairy products to their children, often citing the benefits to health or the convenience of dairy products as factors outweighing ethical concerns. Parents of preschool-age children may therefore compromise these ethical beliefs and provide dairy to their preschool-age child because of the perceived health benefits and convenience associated with dairy.

Environmental concerns, conversely, were identified as a barrier to the provision of both dairy and PBDA. The carbon footprint of the dairy industry and of importing PBDA, and perceived high-water usage in PBDA processing were commonly mentioned environmental concerns. A previous qualitative study with parents of school-age children also found environmental concerns to be a barrier to dairy intake(Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25). The concern, however, was different from the present study’s findings. Jung et al. (Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25) reported that parents were concerned about the environmental effect of pesticide use in non-organic cow feed. More consistent with the present study were results from the study by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Parker and Ameerally26) which reported that adults choosing PBDA over cows’ milk held the perception that dairy is more harmful to the environment due to a higher carbon footprint. While there are no studies comparing dairy and PBDA water use or CO2 emissions due to importing, milk production’s CO2 emissions are less than two times, whereas cheese production’s CO2 emissions are almost 16 times the CO2 emissions of almond- and soya-based beverages(Reference Clune, Crossin and Vereghese33). Some adults, including the parents in the present study, may have a misperception regarding the CO2 emissions of both industries. Nonetheless, the extent to which these environmental concerns affect dairy and PBDA provision to preschool-age children is yet to be determined.

Another facilitator specific to PBDA was the new Canada’s Food Guide. These guidelines also served as a barrier to dairy intake. In 2019, Health Canada updated the Canada’s Food Guide, resulting in less emphasis on dairy products (now included in the ‘Protein foods’ category), and greater emphasis on fruits and vegetables, whole grains and plant-based protein(24). In the present study, some parents who identified themselves as PBDA providers believed these changes supported their choice of providing PBDA over dairy. In addition, in the absence of specific daily serving recommendations in the current version of the new Canada’s Food Guide, many parents expressed their confusion about where dairy fits into the new Canadian guidelines. Some national dietary guidelines, such as those from Brazil and America(34,35) also do not provide serving recommendations, whereas others, for example, European Guidelines, do provide them(36). The present study suggests that the current lack of daily serving recommendations for dairy in Canadian nutrition guidelines is a barrier to dairy intake and may lead to confusion regarding the nutritional interchangeability of dairy with PBDA. In fact, on average, more than one serving of certain types of PBDA is needed to nutritionally equate to a serving of dairy. Specifically, many PBDA contain much lower protein, Ca and/or vitamin D contents, and lower Ca bioavailability(Reference Chalupa-Krebzdak, Long and Bohrer37–Reference Kostecka39). Dietary guidelines should provide clear dairy intake recommendations and instructions on replacing dairy with PBDA without compromising nutritional sufficiency.

Perception of cost is also relevant to the nutritional non-equivalence of dairy and PBDA. Focus group research on dairy has consistently reported that cost is a barrier to dairy intake(Reference Jung, Bourne and Buchholz25,Reference Mobley, Jensen and Maulding28) . The present study is not only consistent with these findings but also showed that perception of the cost of dairy may only be a concern for parents who perceive their children to be consuming a high amount of dairy. Furthermore, the present study extends the barrier of cost to PBDA, showing that parents of preschoolers may perceive that cost of PBDA is higher than that of dairy. This perception is supported by findings from a cost analysis of milk-free diet foods which showed that PBDA are more expensive than cows’ milk(Reference Shah and Towell40). This could mean that parents of preschool-age children, who are considering reducing dairy intake, may choose to replace one serving of dairy with one or fewer servings of PBDA, which are more likely to be nutritionally inadequate(Reference Vanga and Raghavan13,Reference Chalupa-Krebzdak, Long and Bohrer37,Reference Walsh and Gunn38) . Reducing intakes of both dairy and PBDA may present nutritional problems in children, including higher risks of Ca and vitamin D deficiencies(Reference Kostecka39).

In addition to the perceived higher cost of PBDA, some parents identified access as a barrier to consuming PBDA. Parents found some PBDA are difficult to locate in grocery stores, and others noted that they were unable to provide nut-based alternatives in preschool lunches. While little has been reported in the literature about the accessibility of PBDA, access to dairy products, particularly through school milk programmes in Canada and the USA, has been identified as a facilitator to consumption, similar to the results in the present study(Reference Racey, Bransfield and Capello21,Reference Auld, Boushey and Bock41) . Access to nutrient-rich, nut-free PBDA in preschools, especially for children with dairy allergies or intolerance, could be a strategy to promote the consumption of healthy alternative products.

The results of this exploratory study have identified several public health implications. Parents of preschool-age children may be concerned about cost and sugar content of dairy and PBDA, but may not be aware of the nutritional (non)equivalence between both products. Therefore, nutrition education messaging should focus on helping parents find affordable, low sugar or unsweetened dairy and/or PBDA and should emphasise that dairy and PBDA products have variable nutritional composition. Messaging should also focus on educating parents on ways to replace dairy with foods that are nutritionally equivalent to dairy, as well as on the unique health benefits of both dairy and PBDA. These recommendations for future interventions should also be grounded in theory as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Recommendations for interventions promoting healthful dairy and/or plant-based dairy alternatives (PBDA) intake in families of preschool-age children

Implications for future research

The present study provides novel insight about how parents of preschool-age children appraise dairy and PBDA and reports shared and unique barriers and facilitators of dairy and PBDA intake. The study has several implications for future research. First, the results of the present study, specifically parents’ comparisons of dairy and PBDA, reveal the importance of studying dairy and PBDA concurrently when identifying determinants of the provision and intake of either products. Future qualitative studies should inquire about both dairy and PBDA in other subpopulations, such as older adults or adolescents, to identify possible perceived barriers and facilitators, which may be unique to the subpopulation. Second, while a strength of the present study was the inclusion of fathers, this study had lower number of fathers compared to mothers, so future studies should include more fathers to ensure that their perspective is fully captured. Because there may be differences in health beliefs between mothers and fathers(Reference Bassett-Gunter, Levy-Milne and Naylor42), separate mother and father focus groups may be needed to investigate whether there are differences in perceptions towards dairy and PBDA. Third, our results suggest there may be differing perceptions between different PBDA, specifically nut-based v. soya-based. To our knowledge, no study has investigated this, a gap which could be addressed in future studies. Last, survey studies with a large sample of parents of preschool-age children are needed to investigate the extent to which the perceptions found in the present study are held in the general population and the extent to which they may influence dairy and PBDA provision.

Limitations

This study’s results should be viewed in light of its limitations. Focus group results cannot be generalised, but we ensured theoretical saturation was reached by ensuring that no new themes emerged from the analysis of the last focus group conducted. Theoretical saturation increases the likelihood that all possible barriers and facilitators to household provision of dairy and PBDA were identified(Reference Krueger and Casey43). We recruited from a relatively homogenous population comprised mainly of educated Caucasians living in the Guelph area, so our results cannot be generalised to other ethnicities or other Canadian cities. Last, results from a sub-study population may not be generalisable to the general population due to volunteer bias, as individuals choosing to participate in research may not be representative(Reference Callahan, Hojat and Gonnella44).

Conclusion

The present study is the first to provide a comparison of the perceived barriers and facilitators to household provision of both dairy and PBDA in families with preschoolers. This exploration of facilitators and barriers of both products, rather than one or the other, may help inform future interventions targeting the intake of dairy and PBDA. This exploration has also helped to infer recommendations for public health nutrition strategies, including the need to provide clearer messaging on how to replace dairy with nutritionally equivalent foods. Ensuring that preschool-age children’s intake of dairy and/or PBDA (containing equivalent Ca and vitamin D) is adequate could help decrease risk of Ca and vitamin-D deficiencies in childhood and later in adulthood.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We thank the participating families for their time and the research assistants for their help in providing childcare. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: A.L.: Primary author. Formulating the research question and interview guide, moderating focus groups, transcribing then analysing and writing the manuscript. N.T.: Formulating the research question and interview guide, moderating focus groups, transcribing then analysing, writing part of the results and discussion and reviewing the manuscript. E.F.: Assistant moderator in all focus groups and was involved in reviewing the manuscript. Drs H. and M.: Co-lead investigators on the two studies, from which participants were recruited and were involved in reviewing the manuscript. Drs N. and B.: Formulating the research question and interview guide, resolving analysis discrepancies and reviewing the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Guelph, REB #18-10-048. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002100080X