Transformative systems change is needed to resolve global public health nutrition challenges(Reference McLachlan and Garrett1) including the double burden of malnutrition – a worldwide phenomenon representing the coexistence of maternal and child undernutrition (i.e. wasting, stunting and underweight) and micronutrient deficiencies (i.e. iron, vitamin A, iodine and zinc) with child or adult overweight, obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCD) in affected households, communities or populations(2–6).

An estimated 925 million people worldwide are hungry or malnourished(7). Child undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies cause approximately 8 million deaths in children under 5 years of age, contribute to child and adult morbidity(Reference Black, Allen and Bhutta8, 9), and prevent more than 200 million young children from reaching their full developmental potential(Reference Engle and Huffman10). At the other end of the global malnutrition spectrum, about 43 million pre-school children under 5 years(Reference de Onis, Blössner and Borghi11) and approximately 155 to 200 million school-aged children(Reference Wang and Lobstein12) worldwide are overweight or obese. In 2008, an estimated 1·46 billion men and women worldwide were overweight and more than half a billion adults were obese(Reference Finucane, Stevens and Cowan13). Two-thirds of the 57 million global deaths were attributed to lifestyle-related NCD, of which 80 % were in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Horton14, 15).

The double burden of malnutrition will place tremendous pressure on resource-constrained health systems(Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Horton14, 15). An estimated $US 10–12 billion annually is required to scale up thirteen proven nutrition interventions in thirty-six countries to prevent and treat undernutrition(16) and $US 9 billion annually to implement five priority actions to reduce NCD risks globally(Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Horton14).

Partnerships addressing global nutrition challenges

Developing transformative systems change to tackle these global nutrition challenges will require new stakeholder engagement approaches and governance structures that support public- and private-sector participation(Reference McLachlan and Garrett1, Reference Morris, Cogill and Uauy17). UN system organizations(7, 16, 18–20) and public health experts(Reference Daar, Singer and Persad21, 22) have encouraged governments, non-governmental organizations (NGO)(23) and civil society organizations(24) to collaborate with the private sector using public–private partnerships (PPP) to address complex public health challenges (Table 1).

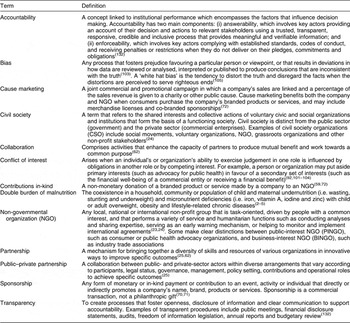

Table 1 Key terms defined (adapted from references 2–5, 17, 23–25, 27, 59, 62, 70–72, 85, 92, 93, 101–105 and 132)

The WHO defines a PPP as a collaboration between public- and private-sector actors within diverse arrangements that vary according to participants, legal status, governance, management, policy setting, contributions and operational roles to achieve specific outcomes(25). Many PPP are social alliances designed to achieve common goals benefiting society and all partners(Reference Austin26, Reference Kraak and Story27). Partnership relationships are defined by engagement level, strategic value of the alliance to each partner's mission, resource investments and managerial complexity(Reference Austin26).

PPP take place within a context of governments being publicly accountable for protecting and promoting the nutritional health of populations. Since the 1980s, governments have increasingly relied on market-driven solutions to address public health nutrition challenges. This trend has been reinforced by WHO in policy documents emphasizing private-sector engagement through partnerships to change the upstream determinants of health(Reference Dixon, Sindall and Banwell28, Reference Richter29).

Several UN system organizations(7, 30, 31) identify global food and beverage companies as important stakeholders to help promote a healthful diet and achieve the human right to food security. It has been suggested that transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies, and their corporate foundations, may be potential collaborators to address global hunger and food insecurity(32), infant and early childhood undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies(Reference Engle and Huffman10, Reference Wojcicki and Heyman33, Reference Yach, Feldman and Bradley34), and obesity and NCD(Reference Kraak and Story27, Reference Yach, Khan and Bradley35).

NGO are important stakeholders to advocate for and implement direct-service programmes reaching disadvantaged populations and protect public health interests by monitoring government and industry actions(24). However, NGO partnerships with global companies have encountered controversy over discordant values, questionable motives, inadequate management of conflicts of interest, endorsement of branded products and marketing strategies, perceived co-option of public health goals by commercial interests, lack of distinction between public- and business-interest NGO, and weak safeguards to protect public health interests(Reference Richter29, Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon36–Reference Oshaug42). NGO partnerships with companies have attracted negative attention that diminishes public trust for an NGO's brand(Reference Neuman43, Reference Shields44). While UN system guidelines are available for private-sector engagement(18, 45, 46), NGO have limited guidelines to navigate and proactively manage the diverse opportunities and challenges presented by partnering with these companies.

In the present paper we describe PPP used to address the global double burden of malnutrition; explore special opportunities and challenges of NGO partnering with transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies; and discuss approaches to help NGO balance the benefits and risks of PPP to effectively target the global double burden of malnutrition.

Methods

We conducted a search of electronic databases (i.e. Academic Search Complete, Health Source and MEDLINE), UN system organization websites and grey literature to identify resources about partnerships and alliances used to address components of the double burden of malnutrition. The authors were also referred to relevant articles and reports by colleagues. We use a narrative summary to present the synthesized evidence acquired from the interdisciplinary literature representing business, public health, nutrition sciences, public policy, risk analysis and ethical perspectives.

Results

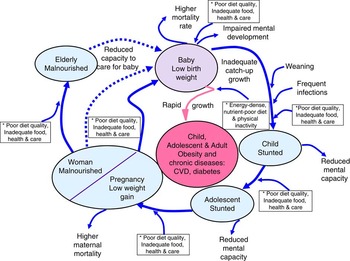

PPP are used to tackle health inequalities, alleviate poverty and promote social innovation for health(Reference Evans and Killoran47, Reference Gehner, Matlin and Sundaram48); expand services for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria(49); distribute vaccines and medications(Reference Widdus50); mitigate global hunger and food insecurity(32, 51, 52); and strengthen community disaster response(53). Partnerships are also used to target the causal links and leverage points for life-cycle susceptibilities associated with the global double burden of malnutrition (Fig. 1)(Reference James, Norum and Smitasiri5), including undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies targeted by the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDG)(20, 49, 54–57); overweight and obesity targeted by WHO's Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health(31); and chronic diseases targeted by WHO's Global Strategy to Prevent and Control Noncommunicable Diseases(58).

Fig. 1 (colour online) Proposed causal links and leverage points* for public–private partnerships to address life-cycle susceptibilities linked to the global double burden of malnutrition (adapted from James et al. (2005)(Reference James, Norum and Smitasiri5))

Evaluations of PPP benefits suggest they can raise the visibility of nutrition and health on policy agendas; mobilize funds and advocate for research; strengthen health-policy and food-system processes and delivery systems; facilitate technology transfer; establish treatment protocol standards; expand target populations’ access to free or reduced-cost medications, vaccines, healthy food and beverage products; and distribute ‘essential packages’ of nutrition assistance during humanitarian crises(Reference Widdus50, Reference Thomas and Fritz59–Reference Buse and Harmer61).

Features of effective partnerships

Donors, governments, transnational companies, corporate and private foundations, NGO and academic institutions can address global malnutrition through diverse interactions, institutional commitments, joint research efforts and multi-sectoral programmes. PPP imply mutuality and equality between partners. Partnerships can be described on a continuum ranging from networking to coordination, cooperation and collaboration(62). Austin(Reference Austin26) describes three types of partnerships – philanthropic, transactional and transformative, discussed below and in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2 Examples of public–private partnerships that address global nutrition challenges (adapted from references 26, 54, 55, 59, 68-69, 73–82 and 85)

NGO, non-governmental organization; WFP, World Food Programme; MCHIP, Maternal Child Health Integrated Program; GAIN, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition; NCD, non-communicable diseases; IFBA, International Food & Beverage Alliance; HWCF, Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation; BINGO, business-interest non-governmental organization; PINGO, public-interest non-governmental organization.

Partnerships may generate tension among the institutional cultures of government, industry and NGO and involve risk taking to produce meaningful change at scale(Reference Fulton, Kasper and Kibbe63). Private-sector partners are often independent of the political mandates of national, state or local governments and they may mobilize more specific expertise and greater capital more efficiently and cost-effectively than public-sector partners. However, private-sector solutions are driven by commercial imperatives to generate profits, can produce inequities and may not reach vulnerable groups. Indeed, corporations have no intrinsic motivation to address existing health or social inequities that are priorities for governments and civil society. These are important tensions to acknowledge when considering a PPP approach.

Effective partnerships develop trusting relationships to share information, technology and promote innovation; leverage financial or in-kind resources, expertise, influence, networks and distribution systems; and manage legitimacy and the collaborative structure to ensure that organizational assets are aligned with common missions, goals and objectives to reach populations with larger-scale activities than each partner can deliver on its own(Reference Austin26, Reference Kraak and Story27, 53, Reference Conway, Gupta and Prakesh64–Reference Lasker, Weiss and Miller67).

Philanthropic partnerships

Philanthropic partnerships involve limited engagement, reciprocity and activities that are peripherally important to each partner's mission. A philanthropic partnership occurs when a company gives a charitable financial or food donation to an NGO either through an anonymous or acknowledged donation accompanied by media coverage for each partner(51, Reference Thomas and Fritz59, 68, 69).

Transactional partnerships

Transactional partnerships build mutually beneficial relationships to advance each partner's agenda through compatibility among organizational values, missions and goals(Reference Austin26). These partnerships involve higher levels of interaction and resource investments compared with philanthropic partnerships. Table 1 defines terms (i.e. contributions-in-kind, co-branded sponsorships and cause marketing)(70–72) that are revenue-raising instruments used by NGO to implement programmes. While transactional partnerships may enhance a company's brand reputation, they can adversely affect an NGO's reputation(Reference Neuman43, Reference Shields44, Reference Thomas and Fritz59). Examples of transactional partnerships(Reference Freedhoff and Hébert39, 73–82) are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Transformational partnerships

Transformational partnerships involve the highest level of engagement, resource investment, managerial complexity and relationships built over time to mutually influence the institutional cultures and practices of each partner. Transformational partnerships involve many partners to stimulate large-scale social or policy changes(Reference McLachlan and Garrett1) to address the double burden of malnutrition (Fig. 1). Examples of aspiring transformational partnerships(54–56, 83, 84) are discussed below and in Tables 2 and 3. Thereafter, we present certain conceptual, practical and ethical challenges.

Maternal and child health integrated programmes to address undernutrition

In 2008, the US government funded the Maternal Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) to accelerate progress towards MDG 4 (reduce infant and child mortality) and MDG 5 (improve maternal health) in thirty priority countries(57). MCHIP uses partnerships with governments and NGO to implement programmes at scale to improve maternal and child nutrition and health(57, 85). In 2011, a global PPP, Saving Lives at Birth, was launched by the US government, private funders, Grand Challenges Canada and the World Bank(86).

Evaluations of child survival programmes suggest that countries achieve the greatest impact by developing strategic PPP supporting mutual programme objectives; responding to each country's specific cultural factors; leveraging each partner's technical expertise and resources to meet clear objectives; and implementing high-impact interventions through scaled-up programmes for broad population coverage(57).

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition to address micronutrient deficiencies

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) is an international alliance that addresses poor health and malnutrition among vulnerable groups by improving their diet quality(55, 56). GAIN is the major convening vehicle for governments, international NGO and private-sector stakeholders to promote food fortification. GAIN reports ‘scaling up 36 large collaborations in 25 countries since 2002 to reach 400 million people with nutritionally enhanced products’(87). GAIN aspires to mobilize $US 700 million of private-sector investment through a Business Alliance(55, 56). GAIN supports partnerships with global food and beverage companies to stimulate market-based solutions that address malnutrition, produce commercial benefits for companies, and encourage economic development in low- and middle-income countries(55, 56, 87).

Evaluations of food fortification programmes in low-income countries suggest that cost-effective and sustainable results are feasible when there is close collaboration among the public sector to improve population health; the private sector, with expertise in food production, technology, marketing communications and consumer reach; and NGO that deliver programmes and services to vulnerable groups(Reference Mannar and van Ameringen88). Independent evaluations of GAIN's Business Alliance are needed to understand the benefits and challenges of using a PPP approach to address micronutrient malnutrition.

International Food & Beverage Alliance and the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation to prevent obesity

The WHO Global Strategies(31, 58) acknowledge that private-sector partners should play a central role in promoting healthy food and eating environments to prevent NCD. In 2008, eight leading food and beverage companies founded the International Food & Beverage Alliance (IFBA) in response to rising obesity rates(83). In 2009, ten IFBA members with a combined annual revenues of $US 350 billion(Reference Yach, Khan and Bradley35) shared a report with WHO(89), suggesting progress had been made to: (i) reformulate and develop new products to improve diets; (ii) provide clear nutrition information to consumers; (iii) extend responsible advertising and marketing pledges to children globally; (iv) raise awareness about balanced diets and increasing physical activity; and (v) support partnerships to promote healthy lifestyles. Independent evaluations have not confirmed IFBA's self-reported progress.

In 2009, the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation (HWCF) was formed in response to the US obesity epidemic as an industry coalition comprised of food, beverage and food retail companies that partners with business-interest NGO (i.e. industry trade associations) and public-interest NGO. The HWCF partners have pledged to make measureable changes to reformulate and expand healthier products in the marketplace, to support worksite wellness, and to promote energy balance education to children in schools(84, 90). In 2010, the HWCF members partnered with private foundations and government through First Lady Michelle Obama's Lets Move! obesity prevention campaign(91). An independent evaluation is underway by academic groups, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, to assess the coalition's progress in making changes in the three settings.

Assessing partnership risks and challenges

All stakeholders involved in PPP are confronted with dilemmas that threaten their goals. PPP evaluations have identified risks that can undermine the appropriateness, effectiveness and credibility of alliances due to: displacing donor priorities with those of recipient countries; excluding certain stakeholders from decision making; neglecting to effectively address conflicts of interest and biases; raising insufficient resources to implement partnership activities and sustain alliances; and inadequately managing human resources(Reference Buse and Harmer61, Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92).

Six challenges discussed below must be addressed to reduce risks to all partners: (i) balancing private commercial interests with public health interests; (ii) managing conflicts of interest and biases; (iii) ensuring that co-branded activities support healthy products and healthy eating environments; (iv) complying with ethical codes of conduct; (v) undertaking due diligence to assess partnership compatibility; and (vi) monitoring and evaluating partnership outcomes.

Balancing commercial and public health interests

Collaborative partnerships provide companies with commercial advantages, yet private commercial interests often conflict with public interests(Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92) and balancing win–loss outcomes is tough. A win–win outcome may be possible to address global food insecurity(32, 52); develop inexpensive and high-quality commercial, complementary food products and integrated marketing communications campaigns that address young child undernutrition in emerging markets(Reference Engle and Huffman10, Reference Wojcicki and Heyman33, Reference Singh, Daar and Singer93); drive product innovation for new consumers(Reference Traitler, Watzke and Saguy66); build community disaster resilience(53); improve the systematic delivery of humanitarian assistance(Reference Thomas and Fritz59); and provide comprehensive integrated packages of nutrition interventions to reach malnourished populations during complex emergencies(Reference Webb60). However, even these partnerships can have unintended consequences and not produce benefits for every partner or target population(Reference Richter29, Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon36). It is arguable whether markets can deliver both short-term financial returns for companies and long-term social, economic and health benefits to address the spectrum of global malnutrition challenges(Reference Richter29).

Current agribusiness-sector models are more compatible with producing and distributing food as a response to hunger and food insecurity than reducing portion sizes or substantially reformulating food and beverage products to improve diet quality and prevent overconsumption(Reference Kraak, Kumanyika and Story94). Concerns relate to any marketing strategy that may increase consumers’ brand loyalty for a company's unhealthy branded product line(Reference Kraak, Kumanyika and Story94) such as promoting bottled water or fortified products that influence the purchase and consumption of branded sugar-sweetened beverages or energy-dense snacks(Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon40). These are relevant concerns for consumers with limited discretionary household incomes, who are vulnerable to persuasive marketing practices and are disproportionately affected by obesity and NCD in emerging markets(Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon36, Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon40, Reference Taylor, Satija and Khurana95). Risks arise when NGO facilitate companies’ access to consumers and influential groups and when partners fail to monitor and evaluate partnership processes and outcomes.

PPP are influenced by global and national government structures. The Codex Alimentarius Commission uses international standards and strong intergovernmental oversight to protect consumer health by promoting global food safety and ensuring fair food trade practices(Reference Somogyi, Hathcock and Biesalski96). Global PPP may identify advantages within the regulatory environment to enhance outcomes, such as providing standards to foster a competitive environment to move industry practices and entire food or beverage product portfolios towards desirable targets to achieve population health benefits(Reference Monteiro, Gomes and Cannon36, Reference Richter97). Examples include the World Action on Salt & Health, a voluntary global initiative that engages governments, industry and NGO to implement strategies to reduce the salt content of processed foods and Na consumption in populations(98); and the Flour Fortification Initiative(Reference Maberly, Grummer-Strawn and Jefferds99), an international network of public and private organizations in the specific context of it encouraging government-regulated and voluntary quality-control systems for Fe fortification of wheat flour to benefit populations in certain countries(Reference Johnson and Wesley100).

Partners must develop mutual trust and open communication to assess where profit-driven activities and public health benefits overlap or conflict. NGO and private-sector companies could dedicate staff and sufficient resources to nurture and sustain partnerships that balance social and health investments with business profits(Reference Austin26). Partners must also anticipate unintended consequences and collaborate to improve the nutrition and health outcomes of targeted populations.

Managing conflicts of interest and biases

NGO and partnering food, beverage and restaurant companies should seek to effectively manage conflicts of interest and biases to establish trustworthy relationships, allay public concerns about compromised partner integrity, reduce the risks to each partner's reputation and minimize unintended consequences for programmes or targeted populations.

Conflicts of interest may arise when NGO staff receive personal gifts or in-kind resources from companies to influence decision making, research or public positions(Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92, Reference Brody101–Reference Brennan, Rothman and Blank104). Further, it is arguable that NGO may be susceptible to ‘white hat bias’(Reference Cope and Allison105), a tendency to disregard facts and distort the truth to serve righteous ends.

Private-sector partners face challenges arising from managing self-dealing conflict of interest. A company's commercial activities may benefit from research generated through a partnership funded by the company's foundation, which may be legally required to act at arms length. Public trust and credibility may be diminished due to the apparent duplicity of private foundations' investments. For example, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has generously supported programmes targeting global health and undernutrition. At the same time, the Foundation has generated a portion of its wealth through direct investments in companies that produce and market products linked to rising obesity and NCD rates, including McDonald's Corporation and The Coca-Cola Company, and indirect investments in Coca-Cola, Kraft Foods and Nestlé through Berkshire Hathaway(Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92).

These considerations do not necessarily preclude PPP but should rather be viewed as opportunities to be addressed to strengthen partnerships. Private-sector partners would be better able to address conflicts of interest by disclosing and improving their accountability for labour, environmental and health-related policies, practices and performance. NGO must be able to independently criticize a private-sector entity for issues unrelated to the partnership to fulfil an important watchdog function to hold governments and industry accountable for public health commitments by exposing non-compliance and inaction(24, Reference Richter29).

Guidelines have been proposed to minimize conflicts of interest and biases related to industry-sponsored research with commercial applications(Reference Rowe, Alexander and Clydesdale103). Organizations could make partnership terms, outcomes and benefits more transparent and explicit through clearly written contracts; incorporate guidelines for managing conflicts of interest into governing bodies’ bylaws; and widely promote written policies and an institutionalized process to standardize expectations for employees to disclose financial and non-financial industry relationships(Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92, Reference Brody101, Reference Brennan, Rothman and Blank104).

Public health professionals and NGO staff who receive industry funding could reject payment or withdraw from institutional decision making(Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee92, Reference Brody101), decline to give industry-sponsored presentations, avoid ghost-writing publications, and turn down consulting arrangements unless governed by clearly written contracts(Reference Brennan, Rothman and Blank104, 106).

Using co-branded activities to support healthy products and healthful diets

Co-branding is apparent in all types of partnerships. NGO should develop criteria and systems for accepting company donations and contributions in-kind that are appropriate to their mission, adhere to standard healthy nutritional guidelines, support local sustainable markets and food systems, align with desirable items distributed through their programmes, and require minimal handling or transportation costs(Reference Thomas and Fritz59, 72).

NGO may be attracted by food and beverage company sponsorship and cause marketing to secure unrestricted funds to support professional societies and conferences(Reference Oshaug42, Reference Brody101, Reference Tobin, Dwyer and Gussow107), nutrition research(Reference Rowe, Alexander and Clydesdale103, Reference Nestle108), programmes(Reference James109) and sporting events(Reference Danylchuk and MacIntosh110). Sponsorship is a commercial activity to promote a company's brand, not a philanthropic gift(70, Reference Rundall71). Risks arise when partners either fail to effectively manage conflicts of interest or engage in duplicitous activities such as concurrent lobbying of legislators to support issues that undermine public health goals(Reference Spolar and Eaton111, 112).

One approach to facilitate decision making about co-sponsoring events is to appoint a brand advisory committee to use a risk-assessment framework with specific criteria to assess the brand, nutrient and event profiles; company marketing and distribution practices; and contextual relevance(113). Obtaining accurate proprietary information about a company's marketing and distribution practices is an ongoing challenge.

Public perceptions about global food, beverage and restaurant company sponsorship favour branded products that have healthy nutritional profiles compared with products with less healthy profiles (i.e. hamburgers, pizza, chocolate bars, salty snacks and sweetened beverages)(Reference Danylchuk and MacIntosh110). NGO and other partners could develop clear criteria about co-sponsored arrangements and align all integrated marketing communications with sponsored products or events to consistently promote public health goals(Reference Danylchuk and MacIntosh110).

Complying with ethical codes of conduct

Codes of conduct raise and maintain public awareness about specific issues, build public pressure to change practices that are detrimental to society, and encourage debate about appropriate standards for corporate conduct(114). Most global food and beverage companies have generally complied with legally binding treaties, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child(115); and voluntary codes of conduct, such as industry self-regulatory programmes to advertise or market responsibly to children(Reference Kolish, Enright and Burke116) and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes(117). In the latter case, there are notable exceptions documented by independent groups when certain companies’ marketing practices continuously violate the Code(Reference Aguayo, Ross and Kanon118–120) while industry-supported, third-party verification mechanisms confirm company compliance(121, 122). These issues cause tension, erode public trust and respect for partners, and diminish the effect of voluntary codes.

Several company pledges have been deemed inadequate to protect children's health and well-being. Many companies’ current marketing practices promote unhealthy products that undermine children's right to a healthful diet(115). Independent evaluations(Reference Lang, Rayner and Kaelin123–Reference Hawkes and Harris127) have documented questionable marketing practices of global companies participating in GAIN, IFBA and HWCF (Table 3) that have not yet been adequately addressed by industry self-regulatory programmes or individual companies, or dealt with in a coordinated way among public-interest NGO. Companies have used their own nutrition guidelines for product reformulation and varied nutrition standards to define healthy products; applied more lenient nutrition criteria for products they manufacture; varied self-regulatory marketing pledges between countries and regions; lacked clear policies on marketing to children and adolescents; excluded packaging, point-of-sale materials, in-school marketing, contributions in-kind and new media from pledges; and made no commitments to stop marketing unhealthy products to children through their parents.

Table 3 Profiles of transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies that use public–private partnerships to address global nutrition challenges (adapted from references 56, 83–84, 87, 89, 90, 134–148)

GAIN, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition; IFBA, International Food & Beverage Alliance; HWCF, Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation.

*Estimated annual revenue represents income that a company receives from its normal business activities from the sale of goods and services to customers. Revenue figures are derived from each company's annual or corporate social responsibility report and/or website.

Shared principles have been proposed for stakeholders to promote infant and young child nutrition(Reference Singh, Daar and Singer93) and reduce the commercial promotion of unhealthy products to children and adolescents(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Lobstein128). Industry self-regulatory programmes are likely to be effective when they establish and widely promote transparent regulatory standards with input from diverse stakeholders, develop meaningful objectives and benchmarks, institute a mandatory public reporting mechanism to show compliance with voluntary codes, and allow evaluations to be conducted by independent groups(Reference Sharma, Teret and Brownell129). The timing is crucial for all stakeholders to implement, monitor and evaluate these principles given WHO's global resolution recommending that Member States substantially reduce marketing practices that promote unhealthy food and non-alcoholic beverage products to children and adolescents(130).

Conducting due diligence to assess partnership compatibility and evaluate outcomes

Frameworks and tools are available, including compatibility assessment criteria (Table 4) and a benefit–risk decision-making pathway (Fig. 2), to help NGO conduct due diligence to select appropriate partnerships for collaborations that promote synergy, transparent decision making and accountability for specific outcomes(Reference Kraak and Story27, 62, Reference Lasker, Weiss and Miller67, 131–133).

Table 4 A tool to assess partnership compatibility between non-governmental organizations (NGO) and transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies to address global nutrition challenges (adapted from reference 27)

Fig. 2 (colour online) A benefit–risk decision-making pathway* for non-governmental organizations (NGO) to engage with transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies through public–private partnerships (PPP) to address the global double burden of malnutrition. *For an NGO to put this decision-making pathway into practice, steps 1–5 are non-negotiable and all need to be ‘yes’ before proceeding with a potential PPP. Step 6 is the ongoing and final decision making required to ensure that the PPP will optimize benefits and minimize risks to all partners and target populations (adapted from WHO (2010)(18), VicHealth (2008)(62), Partnership Governance and Accountability Initiative (2010)(132) and Parramatta City Council (2006)(133))

NGO may already have developed corporate social responsibility profiling, partnership criteria and institutionalized guidelines governing how they partner with companies that manufacture socially unacceptable products (i.e. weapons, tobacco) or engage in egregious practices (i.e. child exploitation, gambling and extractive mining). NGO should also develop partnership profiling, guidelines and criteria to evaluate the totality of partnership activities with transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies, including their compliance with voluntary codes(131–133) and ensure that PPP are harmonized with country strategies, institutions and processes.

Conclusions

The current paper describes partnership opportunities, benefits and challenges; and tools and approaches to help NGO engage with the private sector to effectively address global nutrition challenges. While partnerships may present certain benefits, not all PPP will produce benefits for every partner or target population. PPP challenges include: balancing private commercial interests with public health interests; managing conflicts of interest and biases; ensuring that co-branded activities support healthy products and healthy eating environments; complying with ethical codes of conduct; conducting due diligence; and evaluating partnership compatibility and outcomes. NGO should adopt a systematic and transparent approach using available tools and processes to maximize benefits and minimize risks related to partnering with transnational food, beverage and restaurant companies to effectively target the global double burden of malnutrition.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: V.I.K. received PhD scholarship support to complete this paper through Deakin University's Population Health Strategic Research Centre in the School of Health and Social Development. The other authors declare that they received no additional funding to develop this paper. Conflict of interest: V.I.K., M.L., P.J.H., M.A.J. and B.S. have no conflict of interest. P.B.H. is employed by Save the Children, which in the USA has received funding to support several programme areas. Among these supporters are The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, General Mills Foundation, Kidfresh, Kraft Foods and Kraft Foundation, PepsiCo Foundation, Wal-Mart Foundation and the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Foundation. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Save the Children Federation, Inc. Author contributions: V.I.K. developed the initial concept, conducted the literature review, and wrote the first draft of the paper. P.B.H., P.J.H., M.L., M.A.J. and B.S. further developed the concepts, identified additional references, and contributed to subsequent drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful for the insightful comments provided by the anonymous reviewers. They also thank Drs Bill Dietz, Cecily Hunter, Shiriki Kumanyika and Andre Renzaho, as well as Sana Chehini, Adrian Ng'asi and Brendan Wackenreuter, for providing helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.