According to the WHO, more than 1 billion adults worldwide are overweight and at least 300 million of them are obese( 1 ). Obesity is associated with numerous diseases, such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, heart disease and obesity-related cancers( Reference Dixon 2 , Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 3 ); thus, preventing and controlling this metabolic condition has imperative public health impact. While a causal relationship between sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and obesity remains unclear, numerous studies suggest that increased SSB consumption may lead to weight gain in both adults and children( Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 3 , Reference Vartanian, Schwartz and Brownell 4 ). One possible explanation is that SSB, especially high intake of energy-dense SSB, increase total energy consumption to a point where it surpasses total energy expenditure( Reference Vartanian, Schwartz and Brownell 4 , Reference Bachman, Baranowski and Nicklas 5 ). Additionally, SSB generate low satiety and may encourage individuals to consume more foods per meal, leading to a higher total daily energy intake( Reference Almiron-Roig, Chen and Drewnowski 6 , Reference Johnson, Appel and Brands 7 ). Both mechanisms may ultimately lead to unintentional weight gain.

Ecological data support the aforementioned association between SSB and obesity, as the consumption of SSB has increased in parallel with the escalating prevalence of obesity in many countries( Reference Drewnowski and Bellisle 8 ). For example, in Mexico, the prevalence of obesity among adults has increased dramatically since the late 1980s, with a 4 % increase from 2000 to 2006( Reference Ford and Mokdad 9 ). Concurrently, the percentage of Mexican households consuming soda increased by 22 % from 1989 to 2006( Reference Vergara-Castaneda, Castillo-Martinez and Colin-Ramirez 10 ). In Mexico, SSB now contribute approximately 8–9 % of total energy intake, making this country the second largest soda consumer in the world( Reference Vergara-Castaneda, Castillo-Martinez and Colin-Ramirez 10 ).

A similar nutrition transition is taking place rapidly in other Latin American countries where urbanization has led people to become more sedentary while adopting a diet that is high in refined sugars( Reference Kain, Vio and Albala 11 , Reference Popkin 12 ), heightening the public health concern of a predominantly overweight population( Reference Popkin 12 , Reference Popkin and Doak 13 ). Indeed, the prevalence of obesity is extremely high in Latin American countries( Reference Filozof, Gonzalez and Sereday 14 ), including an upward trend observed in Costa Rica. In Costa Rican women aged 20–44 years, the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased steadily from 35 % in 1982 to 46 % in 1996( 15 ). By 2009, 60 % of Costa Rican women in this age range were considered overweight( 15 ). A similar trend was observed in men aged 20–64 years, among whom the prevalence of overweight increased from 22 % in 1982 to 62 % in 2009( 15 ).

Unfortunately, there are limited data on consumption of SSB and any potential relationship with adiposity in Latin American countries. Therefore, we investigated whether SSB consumption is associated with overweight and obesity status using BMI and other anthropometric measurements in Costa Rican adults.

Experimental methods

Study population

All data for the present analysis came from control subjects of a population-based case–control study on diet and heart disease conducted in Costa Rica from 1994 to 2004. The details of that study are described elsewhere( Reference Colon-Ramos, Kabagambe and Baylin 16 ). Controls were randomly selected from the National Census and Statistics Bureau of Costa Rica, and matched with cases of a first acute myocardial infarction for age, sex and area of residence. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Harvard School of Public Health and the University of Costa Rica. All participants gave informed consent and the participation rate for controls was 88 %.

Data collection

Trained personnel visited study participants at their homes to collect anthropometric measurements and conduct interviews using closed-ended questions to attain data on sociodemographic characteristics, smoking, physical activity and medical history. Details of the anthropometric measurement collection method are explained elsewhere( Reference Campos, Bailey and Gussak 17 ). All anthropometric measurements were taken with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes, collected in duplicate and averaged for analyses. Fieldworkers measured triceps (posterior upper arm, midway between the elbow and acromion), subscapular (1 cm below the lower tip of the scapula) and suprailiac (at the midline and above the iliac crest) skinfold thicknesses using Holtain skinfold callipers. All measurements were taken on the right side of the body. Non-stretchable fibreglass or metal tapes were used to measure the waist (smallest horizontal trunk circumference) and hip (largest horizontal circumference around the hip and buttocks) girths. A steel anthropometer and a Detecto bathroom scale or a Seca Alpha Model 770 digital scale accurate to 50 g were used to measure height and weight, respectively. The two scales were calibrated every other week. BMI was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in metres).

Dietary intake was assessed using the semi-quantitative FFQ that was developed and validated specifically for the Costa Rican population( Reference Baylin, Kabagambe and Siles 18 – Reference Kabagambe, Baylin and Siles 21 ). The following sweetened beverage items were assessed: Coke, Pepsi and other sodas (1 can, 12 oz); Caffeine Free Coke, Pepsi and other sodas (1 can, 12 oz); orange juice (1 glass, 8 oz); other fruit juices (1 glass, 8 oz); commercially available sweetened beverages (1 serving, 8 oz); and ‘fresco’ (1 glass, 8 oz). Fresco is a popular traditional home-made beverage in Latin America that is often made by blending together fresh fruits, sugar and water. Commercially available sweetened beverages were defined as ‘fruit drinks’, while natural home-made juices squeezed from various fruits, mainly orange juice (76 %), were combined into the category ‘fruit juice’. The variable ‘soda’ consisted of all sugar-sweetened soda beverages, which were mostly regular Coke, Pepsi and other colas (84 %), followed by caffeine-free sodas (16 %).

Statistical analysis

The original population consisted of 2274 participants and 27 % of them were women. Participants with missing data on BMI (n 25), skinfold thickness (n 21), SSB consumption (n 38) and potential confounders (n 145) were excluded from the present analysis. Thus, a total of 2045 participants (90 % of the total studied population) were included. In order to look at the distribution of demographic characteristics, age, which ranged from 18 to 86 years, was categorized into three age groups (≤44, 45–64 and ≥65 years) and income was categorized into tertiles. All beverage intakes were divided into the following three categories based on the frequency of consumption: never; >0 and <1 serving/d; and ≥1 serving/d. Differences in group means and in the distribution of continuous and categorical variables were assessed by performing ANOVA and χ 2 tests, respectively, using ‘never’ as the reference category. We did not find significant differences in demographic characteristics between excluded and included participants.

Multivariate regression was used to estimate least square means and β coefficients for the association between SSB and continuous markers of adiposity, including BMI, waist-to-hip ratio and subscapular, suprailiac and triceps skinfold thickness. The main model was adjusted for age, sex, education, income, area of residence, smoking and physical activity. Subsequent models considered other food items that have been shown to be associated with SSB consumption: intake of added sugars, dietary fibre intake, alcohol intake, PUFA:SFA intake ratio and, depending on the model, consumption of other SSB other than the main exposure. None of these variables altered the initial model and thus were not included for the final analysis. To determine if total energy intake would mediate the association between SSB and adiposity outcomes, we adjusted for total energy intake in a separate model. All P values were two-sided and analyses were performed at the α = 0·05 level. The SAS statistical software package version 9·1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The average demographic and anthropometric characteristics, as well as average beverage intakes, are presented by sex and three categories of BMI in Table 1. Men with higher levels of income were more overweight and obese. Current smokers tended to have lower BMI, both males and females. Men who drank fruit drink and fruit juice ≥1 serving/d, and women who drank soda ≥1 serving/d, presented higher frequencies of obesity compared with those who never drank. Fresco, fruit drink, soda and fruit juice were consumed ≥1 time/d by 47 %, 14 %, 4 % and 14 % of the population, respectively (data not shown).

Table 1 Demographic and anthropometric characteristics and SSB intake by sex and BMI category, men and women aged 18–86 years (n 2045), Costa Rica

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; MET, metabolic equivalents.

†Fresco is defined as intake of home-made, non-commercially available, sugar-sweetened fruit beverage.

‡Fruit drink is defined as intake of commercially available SSB.

§Fruit juice is defined as intake of natural orange juice and other fruit juices made at home.

∥Differences in BMI were significant across continuous and categorical variables, as assessed by ANOVA and χ 2 tests, respectively: P < 0·05.

We examined general characteristics and potential confounders by frequency of intake of different SSB (Table 2). In general, males and younger participants consumed more SSB. Participants who consumed ≥1 serving fruit juice/d were less physically active than those who did not consume it. Participants who consumed ≥1 serving SSB/d, except for fruit drinks, had higher years of education and income, while those who never consumed SSB had lower energy intake than those who did. Consumption of more fresco and fruit juice but less fruit drink was observed among those residing in urban and peri-urban areas.

Table 2 Potential confounders by category of SSB intake, men and women aged 18–86 years (n 2045), Costa Rica

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; MET, metabolic equivalents.

† Fresco is defined as intake of home-made, non-commercially available, sugar-sweetened fruit beverage.

‡ Fruit drink is defined as intake of commercially available SSB.

§ Fruit juice is defined as intake of natural orange juice and other fruit juices made at home.

∥Values were significantly different from those of the reference group (‘never’), as assessed by ANOVA and χ 2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively: P < 0·05.

Overall, higher consumption of SSB was associated with increased measures of adiposity (Table 3). Increased soda intake was associated with an increase in BMI. Those who consumed ≥1 serving soda/d had 6 % higher mean BMI than never drinkers. Participants who consumed soda <1 serving/d and ≥1 serving/d had 2 % and 14 % higher total skinfold thickness, respectively (P = 0·02), than those who did not consume soda (data not shown). Increased fruit drink intake <1 serving/d and ≥1 serving/d was associated with 3 % and 4 % increases in mean BMI, respectively (P = 0·007). Those who consumed ≥1 serving fruit drink/d had 4 % higher waist-to-hip ratio than never drinkers (P = 0·004). Subscapular skinfold thickness was higher in those who consumed ≥1 serving fruit juice/d compared with never drinkers (17·3 v. 16·1 mm, P = 0·04); no other measures of adiposity were significantly associated with fruit juice intake. Those who consumed fresco <1 serving/d and ≥1 serving/d had significantly higher mean skinfold thickness at the three measured sites, with total skinfold thickness being 0·5 mm and 2·6 mm thicker than for never drinkers (P = 0·01, data not shown). Increased consumption of fresco was not associated with BMI or waist-to-hip ratio. None of the results reported in Table 3 were altered when we adjusted for total energy intake in a separate model.

Table 3 Adjusted mean adiposity measurements by category of SSB intake, men and women aged 18–86 years (n 2045), Costa Rica

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

†Means are adjusted for age, sex, education, income, area of residence, smoking and physical activity.

‡Fresco is defined as intake of home-made, non-commercially available, sugar-sweetened fruit beverage.

§Fruit drink is defined as intake of commercially available SSB.

∥Fruit juice is defined as intake of orange juice and other fruit juices made at home.

¶Mean values were significantly different from those of the never category: P < 0·05.

††Mean values were significantly different from those of the >0 and <1/d category: P < 0·05.

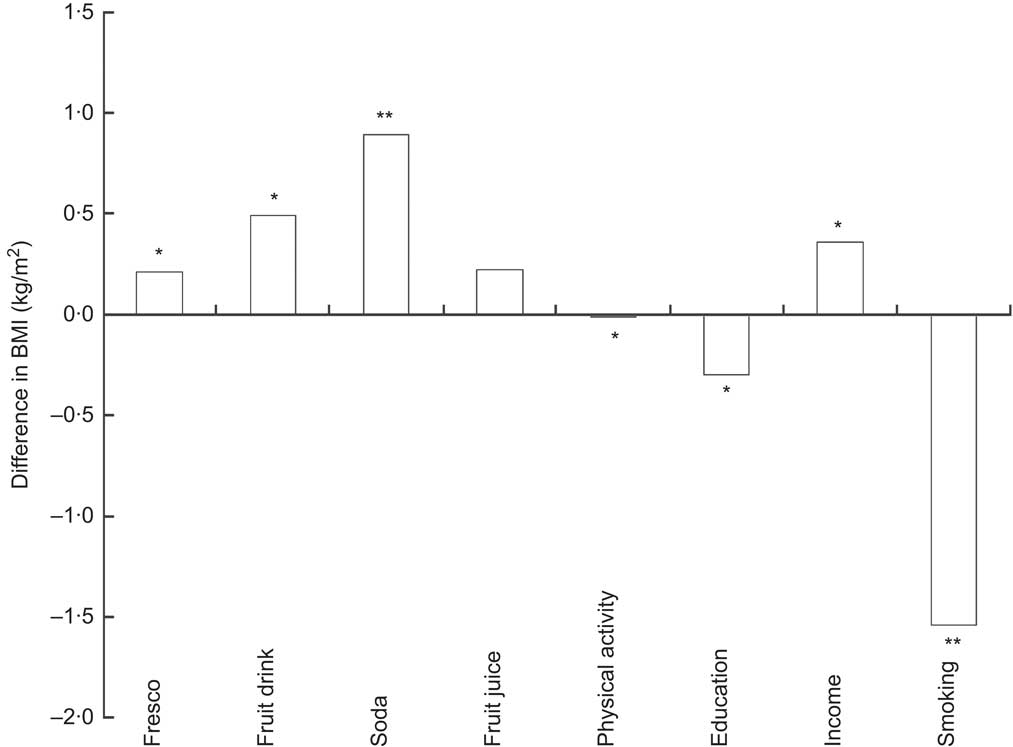

We also examined the associations between the four different SSB and lifestyle factors, and difference in BMI, adjusted for age and sex (Fig. 1). An increase in soda or fruit drink consumption of 1 serving/d was associated with 0·89 kg/m2 and 0·49 kg/m2 higher BMI, respectively (P = 0·001 and 0·0005, respectively). A 1 serving/d increase in fresco consumption was associated with 0·21 kg/m2 higher BMI (P = 0·04). Additional servings of fruit juice were not significantly associated with increases in BMI. An increase in physical activity of 1 sd (14·3 MET (metabolic equivalents)/d) was associated with 0·01 kg/m2 lower BMI. Education and income were associated with BMI in opposite directions: 1 sd (5·44 years) increase in education was associated with lower BMI (−0·30 kg/m2), whereas 1 sd ($US 427/month) increase in income was associated with higher BMI (+0·38 kg/m2). Smoking was significantly associated with lower BMI (−1·54 kg/m2, P < 0·0001).

Fig. 1 Differences in BMI (kg/m2) for varying units of intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and lifestyle factors, men and women aged 18–86 years (n 2045), Costa Rica. The units for each exposure variable and lifestyle factor are as follows: fresco: an increase of 1 glass/d (8 oz); fruit drink: an increase of 1 serving/d (8 oz); soda: an increase of 1 can/d (12 oz); fruit juice: an increase of 1 glass/d (8 oz); physical activity: an increase of 1 sd (14·3 MET (metabolic equivalents)/d); education: an increase of 1 sd (5·44 years); income: an increase of 1 sd ($US 427/month); and smoking. The model was adjusted for age, sex and total energy intake. All P values were significant at the α = 0·05 level except for fruit juice.* P < 0·05; ** P ≤ 0·0001

Discussion

The present analysis shows that increased intake of SSB, especially commercially available SSB such as fruit drinks and soda, is significantly associated with higher measures of adiposity including BMI and waist-to-hip ratio. Stronger associations were found for commercially available SSB (soda and fruit drink) than for traditional fresco or fruit juice. An increase of 1 soda or fruit drink/d was associated with higher BMI. Increasing servings of fresco were also associated with higher BMI, although to a lesser extent. Intake of ≥1 fruit drink or soda/d was also associated with higher waist-to-hip ratio compared with no intake.

Epidemiological data, including evidence from large prospective cohort studies and short-term feeding trials, strongly support the hypothesis that higher intake of SSB is associated with a higher risk of obesity( Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 3 , Reference Vartanian, Schwartz and Brownell 4 , Reference Malik, Popkin and Bray 22 – Reference Tordoff and Alleva 24 ). The major findings of our study are consistent with those reports. For example, results from analysis conducted with data of the Nurses’ Health Study II showed that an increased intake of SSB over two 4-year periods resulted in the largest amount of weight gain, and an increased intake of fruit punch was also associated with weight gain( Reference Schulze, Manson and Ludwig 23 ). It has been hypothesized that, in addition to the weight gain due to increased energy intake, other mechanisms could lead to the increased overweight associated with higher SSB intake( Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 3 , Reference Malik, Popkin and Bray 22 ). The observed positive associations between SSB intake and increased adiposity after adjusting for total energy in the present study are in agreement with this hypothesis.

Our study findings show that the association between soda and commercially available fruit drinks and obesity is stronger than the association between traditional home-made drinks (fresco) and obesity. This could have important public health implications in Latin American countries where there has been an upward trend in soda consumption. For example in Chile, SSB are one of the top three food items purchased( Reference Albala, Vio and Kain 25 ), and in Mexico, soda purchases have been increasing from 1984 to 1998( Reference Rivera, Barquera and Campirano 26 ). In our study, only 4 % of the adults consumed ≥1 can of soda/d while 14 % of them consumed ≥1 serving of commercially available fruit drink/d. Although this is a low intake of soda compared with intakes in other Latin American countries, consumption was higher for younger adults, highlighting the importance of targeting programmes that seek to control advertising of soda and other commercially available sweetened beverages towards younger adults to prevent weight gain and obesity at older ages. The potential long-term effects of fresco consumption on overweight and obesity in the Costa Rican population should not be ignored. Although the association between increased servings of fresco and BMI was not as strong as that between increased servings of soda and BMI, a higher percentage of our participants consumed fresco (47 %) compared with soda (4 %). As such, the potential impact of fresco on health should be examined further and be addressed in Costa Rican dietary recommendations in the future.

Based on earlier findings, it has been hypothesized that the burden of obesity shifts to disadvantaged groups with lower socio-economic status, especially in low-income countries( Reference Boissonnet, Schargrodsky and Pellegrini 27 – Reference Singh, Siahpush and Hiatt 29 ). CARMELA, a cross-sectional, population-based observational study done in seven major Latin American cities, supported this hypothesis by showing an inverse gradient between socio-economic status and BMI, waist circumference and metabolic syndrome in women( Reference Boissonnet, Schargrodsky and Pellegrini 27 ). In a recent trend study published by Singh et al.( Reference Singh, Siahpush and Hiatt 29 ), higher obesity prevalence was observed in immigrants in the USA with lower education, income and occupation levels in each time period examined, but over time higher socio-economic groups experienced more rapid increases in prevalence. In our study, higher income was associated with higher BMI. Overweight and obesity prevalence has been increasing rapidly in Latin America, and this emerging problem could partially be explained by rapid socio-economic development and urbanization and adoption of Western diet patterns and sedentary behaviours( Reference Cuevas, Alvarez and Olivos 30 ). For developing countries, a higher socio-economic level may allow individuals to afford ‘Western’ foods and beverages, including commercial SSB, which tend to be more costly than the traditional drinks( Reference Bermudez and Tucker 31 ). Such findings render support to the notion that improved socio-economic status and lifestyles are associated with an increased risk of obesity( Reference Heidi Ullmann, Buttenheim and Goldman 28 , Reference Cuevas, Alvarez and Olivos 30 , Reference Kain, Vio and Albala 32 ). Opposite to the results for income, we observed that higher education was associated with lower BMI. While a report showed that education has a minimal effect on obesity among foreign-born Hispanics living in the USA( Reference Barrington, Baquero and Borrell 33 ), intake of added sugar has been inversely associated with educational attainment in US Hispanic men( Reference Thompson, McNeel and Dowling 34 ). Although education and income tend to be linked, higher education may counterbalance the association between high income and obesity, as individuals become well informed about health and diet in general. Therefore, considerations should be given to obesity prevention measures that seek to improve education along with socio-economic progress in Latin American countries.

A major strength of the present study is the separate analysis of commercially prepared and home-made traditional beverages rather than a combined analysis. This allowed us to determine differences in association with adiposity by type of beverage and provide targeted recommendations on limiting intake of specific types of beverages. The study also benefited from a large sample size, high participation rate and the use of detailed dietary assessment using the standardized FFQ designed and validated specifically for Costa Ricans. A main limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which cannot establish directionality of the association. Our study results may be applicable only to other Hispanic ethnic groups with similar patterns of beverage consumption. As there are scarce data on such dietary preferences among Hispanics( Reference Filozof, Gonzalez and Sereday 14 ), our study is a major contribution to such body of work and encourages future epidemiological research in this field, particularly in Latin America.

Conclusions

Increased intake of commercially available SSB could partly explain the increasing prevalence of obesity in Latin America. Whether preventing SSB consumption will stop or diminish levels of obesity warrants further examination, but our results are consistent with other study findings and possible biological mechanisms that could explain weight gain from increased intake of SSB. Because obesity and overweight are major risk factors for various chronic diseases, it is important to establish dietary recommendations that can raise public awareness on the potential health risks of high consumption of SSB.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants HL49086, HL60692 and AG00158 from the National Institutes of Health. There is no conflict of interest to declare. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the whole manuscript. J.J.R. conducted statistical analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. J.M. and H.C. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical revision of the manuscript. H.C. conceptualized and designed the study.