Several decades of research has found that parents play an important role in determining what their children eat, shaping their children’s eating habits and impacting their children’s weight outcomes( Reference Lumeng, Ozbeki and Appugliese 1 – Reference Zeinstra, Koelen and Kok 3 ), referred to collectively as food parenting. In cross-sectional, longitudinal and intervention studies, researchers have examined both general food parenting style (e.g. permissive feeding, authoritarian feeding) and more specific feeding practices (e.g. restriction, pressure to eat), as well as how these practices relate to child health and weight-related outcomes (e.g. weight status, eating behaviours)( Reference Blissett 4 – Reference Papaioannou, Cross and Power 6 ).

Despite consistent findings that parents play an important role in shaping their children’s long-term eating and weight-related outcomes, specific findings have been mixed. These discrepancies may be due in part to different conceptualizations of food parenting. For example, a recent review( Reference O’Connor, Pham and Watts 7 ) identified seventy-nine published instruments (1392 items in total) for measuring food parenting practices. Across the instruments, researchers often used different labels for similar, overlapping and/or identical constructs (e.g. offering dessert in exchange for eating dinner is sometimes classified as ‘food as reward’ and other times classified as ‘pressure to eat more’). Similarly, another review found that measures of food parenting practices vary widely in quality( Reference Vaughn, Tabak and Bryant 8 ). In response to the disparate nature of the food parenting literature, researchers( Reference Pinard, Yaroch and Hart 9 ) have concluded that the field needs to agree upon a single conceptualization of food parenting and use standard measures with strong psychometric properties.

To address this need, two valuable approaches have been initiated. First, O’Connor and colleagues( Reference O’Connor, Pham and Watts 7 ) began the development of an item bank for food parenting practices, comprising both published items and qualitative surveys of parents. Thus far, the authors have grouped the roughly 400 items generated into representative concepts (i.e. control, autonomy promotion, structure of food environment, responsiveness, consistency of feeding environment, behavioural and educational, and emotion regulation). Eventually, this item bank will be able to be used within a Computerized Adaptive Testing environment, where the presented items are tailored based on the responses given, so that participants can complete relevant items and results can be compared across studies.

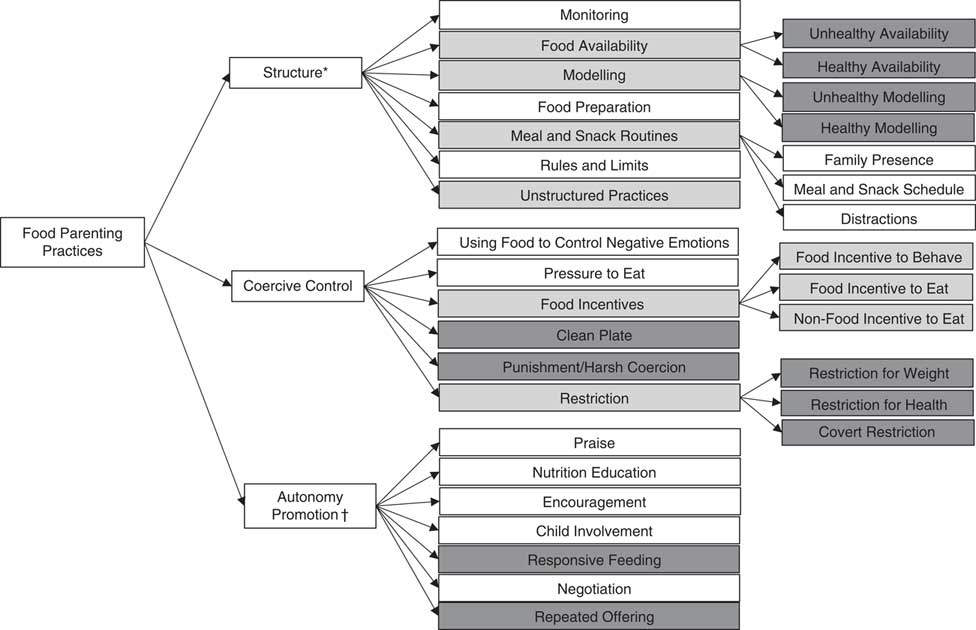

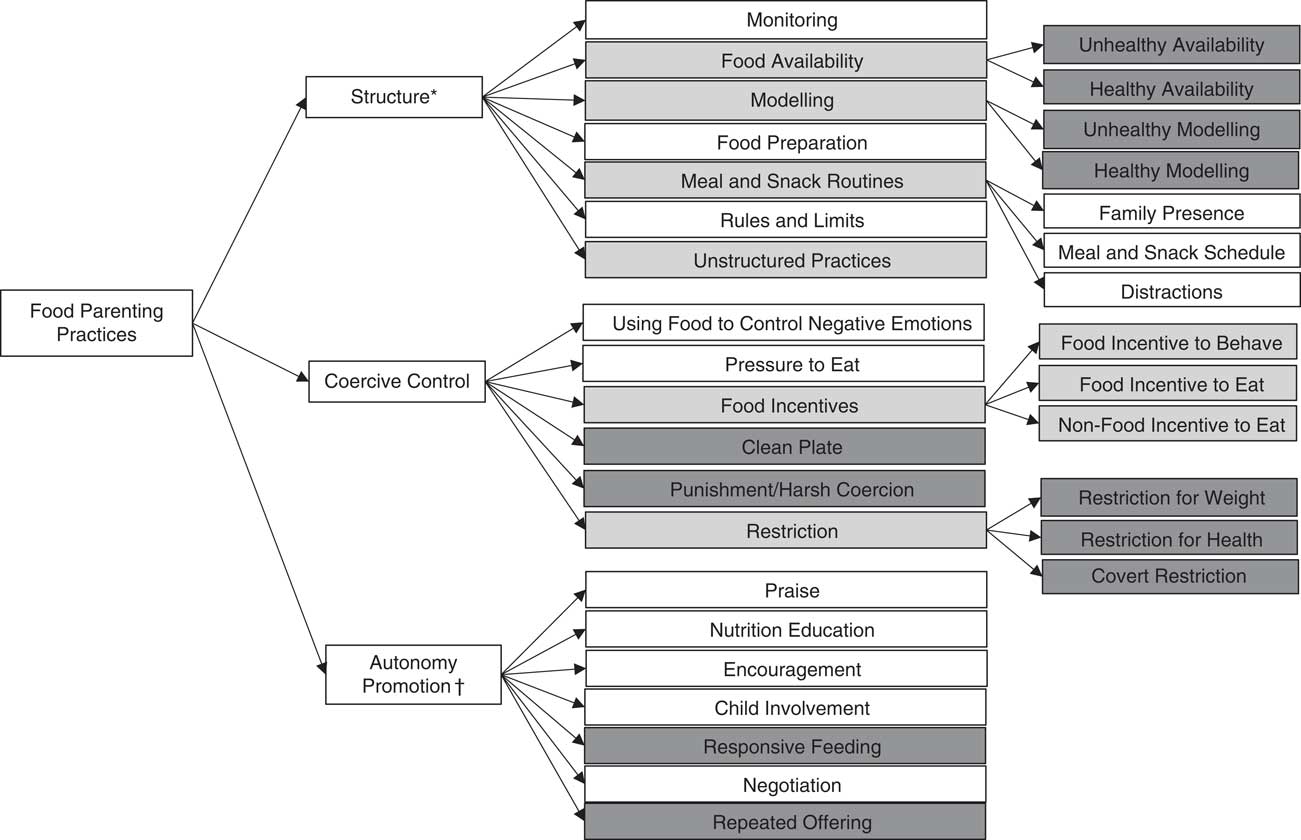

Meanwhile, a second effort has approached this issue from a top-down direction. Namely, a team of experts collaborated to outline a content map to guide the conceptualization and naming of various food parenting practices( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ). The resulting content map included three broad food parenting constructs: Coercive Control, Structure and Autonomy Promotion, each of which is comprised of several sub-constructs (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Map of food parenting practices used in the present study (![]() , construct same as Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

);

, construct same as Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

); ![]() , construct similar to Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

);

, construct similar to Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

); ![]() , construct not represented in Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

)). Constructs from Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

) not included in the present study: *Limited/Guided Choices, Atmosphere of Meals, Food Accessibility, Neglect and Indulgence (Structure); †Reasoning (Autonomy Support)

, construct not represented in Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

)). Constructs from Vaughn et al.

(

Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher

10

) not included in the present study: *Limited/Guided Choices, Atmosphere of Meals, Food Accessibility, Neglect and Indulgence (Structure); †Reasoning (Autonomy Support)

However, despite these important steps, little research has yet examined parents’ reports of their use of the constructs and sub-constructs proposed in Vaughn et al.’s( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) concept map. Thus, the goal of the current study was to measure the broad range of food parenting behaviours in the three domains identified in the conceptual framework (Structure, Control and Autonomy Promotion). Drawing from existing measures that map on to these constructs, we sought to examine the fit of this concept map to empirical data from mothers and fathers, to examine the stability of these reports over a short interval and to describe the extent and ways in which parents report using these practices.

Methods

Measures

Parents responded to 166 items, drawn from several sources. Items from three broad scales of food parenting practices were included: (i) the Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire (CFPQ; forty-nine items)( Reference Musher-Eizenman and Holub 11 ); (ii) the Meals in our Household structure subscale (MioH; ten items)( Reference Anderson, Must and Curtin 12 ); and (iii) the Feeding Strategies Questionnaire (FSQ; thirteen items)( Reference Berlin, Davies and Silverman 13 ). These measures were selected for their inclusion of the constructs described in the concept map. For example, most measures of food parenting do not include explicit measures of structure, so the items from the MioH were important to represent these aspects of the concept map. Some items from the MioH and the FSQ were not included because they duplicated CFPQ items or they were not relevant to parental feeding practices (e.g. ‘My child knows when s/he is full’). In addition, we reviewed items from published instruments and representative food parenting concepts reviewed by O’Connor et al. ( Reference O’Connor, Pham and Watts 7 ) that were not included in the above three instruments, which yielded an additional fifty-two items. Finally, we generated additional items (forty-two items) for the constructs outlined by Vaughn et al.’s( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) concept map which were not well represented by the final item set and could not readily be found in extant measures of food parenting. All items were worded in the first person (e.g. ‘I let my child …’) and most were measured on a 5-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘always’, except for items from the FSQ which were measured on a scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

Data collection procedure

Parents of 2·5–7-year-old children were recruited to participate. Children younger than 2 years have unique feeding issues that are not well captured by this concept map (e.g. bottle use) and children older than 8 years begin to make more independent eating decisions. Thus, this age range captures a typical range for the study of food parenting. Parents were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an online platform where hundreds of thousands of members can complete jobs (such as surveys) over the Internet. Participants can be screened for specific characteristics such as US residency. Although Mturk has both strengths and limitations like any source of data( Reference Chambers and Nimon 14 ), several empirical studies have indicated that samples recruited in this manner match the demographics of the USA more closely than typical convenience or Internet samples and yield high-quality data( Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz 15 – Reference Paolacci, Chandler and Ipeirotis 17 ). Mturk has been used successfully to conduct research on eating habits in general and food parenting practices specifically( Reference Kiefner-Burmeister, Hoffmann and Zbur 18 , Reference González-Vallejo and Lavins 19 ). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Parents who agreed to participate were given the link to the online survey hosted on Qualtrics. The first page of the survey presented an explanation of the general purpose, methods, and risks and benefits of the study, and explained that participants were indicating their informed consent by continuing to the first set of items. The survey included items about food parenting practices and demographic questions. It also featured several other questionnaires which were not examined in the present study. After participants completed the food parenting items, the survey software randomly selected four of the behaviours that the parent reported doing ‘often’ or ‘always’ and asked a set of open-ended, follow-up questions about these behaviours. All follow-up questions took the form of, ‘Earlier you said that you often or always (e.g. offer your child his/her favourite foods in exchange for good behaviour). Please briefly tell us more about the last time that you did this.’ Follow-up questions were intended to capture a qualitative view of parents’ interpretation of the items to provide an understanding of how parents are using these food parenting practices with their children.

Data were screened for patterned responses (e.g. the same response for every item on a scale), incorrect responses to several quality control questions (e.g. please select ‘agree’ for this item), inappropriate responses to the open-ended questions (e.g. off-topic comments) and total survey completion time (under 10 min). Fewer than 10 % of those who completed the survey were rejected, with incorrect responses to quality control items being the most common reason (4 %). Participants were compensated $US 0·75 for completion of the survey. Participants were also asked if they would like to complete a follow-up survey two weeks later for an additional $US 0·25. This follow-up survey contained the food parenting items (other than the twenty-three MioH and FSQ items which had been previously removed as they duplicated items from other scales or measured something other than parental feeding practices such as child satiety) to assess test–retest reliability (n 122). All procedures were approved by the Bowling Green State University Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment.

Analysis procedure

Factor analysis and scale formation

For each of the three broad domains, Pearson’s r correlations were calculated between the subscales to understand the bivariate relationships among these constructs. To test whether the a priori factor structure would fit the data, exploratory factor analyses with maximum likelihood extraction and promax rotation were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 on subsets of items corresponding to the three broad domains of Coercive Control, Structure and Autonomy Promotion. Factor loadings were examined to ascertain which items related most closely to one another and, whenever possible, factors were mapped on to constructs defined by Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) (see Fig. 1). The number of factors to retain was based on an examination of eigenvalues over 1 and the break point in the scree plot (which yielded the same number of factors in these models) Bivariate correlations among the three domains were also calculated to understand how Coercive Control, Structure and Autonomy Promotion related to one another in this sample.

Qualitative responses

Parents’ responses on the open-ended questions were analysed through systematic coding. Three pairs of coders (all authors) initially coded responses based on whether the content of each individual response indicated that the participant understood the item, misunderstood the item, or provided unrelated or insufficient information (e.g. ‘I did this yesterday’, ‘always’). Agreement was very high (κ = 0·99). Any discrepancies between coders were resolved by a third coder (one of the first four authors), blind to coding pairs. Open-ended items with five or more responses were analysed.

Test–retest reliability

To examine the stability of parents’ responses over a two-week interval, Pearson’s correlations were calculated between the subscale scores obtained at the two time points (i.e. the original sample and the subset of participants who completed the follow-up survey two weeks later).

Results

Participant description

The sample included 118 fathers and 376 mothers (and two parents who did not specify their gender) of children between the ages of 2·5 and 7 years (mean 4·7 (sd 1·1) years) living in the USA. The mean age of fathers was 33·0 (sd 7·0) years and of mothers was 32·4 (sd 6·5) years. The sample was geographically diverse, representing forty-nine of the fifty states, with no more than 8 % from any one state (California). The sample featured some racial diversity (79 % Caucasian, 8 % African-American, 5 % Multiracial, 4 % Hispanic and 2 % Asian). The median reported household income category was $US 50 000–80 000 (with 7·5 % of the sample reporting an income of under $US 20 000 and 17·4 % reporting an income of greater than $US 80 000). The median educational attainment was an associate’s degree (with 10·9 % of the sample reporting a high-school education and 45·8 % reporting at least a bachelor’s degree). Of the original sample, 122 parents completed the follow-up survey. Those who completed the follow-up did not differ from those who did not on any demographic characteristics (all P >0·10).

Factor analyses

Across the factor analyses, twenty items loaded below 0·20 on any factor and were therefore excluded from the final measure. The items that loaded below 0·20 on any factor can be found in Table 1 and the factor loadings for all remaining items can be found in Tables 2–4.

Table 1 Food parenting practice items that loaded below 0·20 on any factor in the current sample of mothers and fathers and were excluded from the final model

Table 2 Items and factor loadings of all food parenting items that loaded on Structure subscales

Table 3 Items and factor loadings of all food parenting items that loaded on Coercive Control subscales

Table 4 Items and factor loadings of all food parenting items that loaded on Autonomy Promotion subscales

Structure

Vaughn et al.’s( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) concept map for Structure included nine factors: rules and limits, limited/guided choices, monitoring, meal and snack routines, modelling, food availability, food accessibility, food preparation, and unstructured practices. The meal and snack routines factor was further broken down into the following factors: atmosphere of meals, distractions, family presence, and meal and snack schedule. The unstructured practices factor was further broken down into neglect and indulgence.

The factor analysis of the Structure items mapped well on to some of these constructs but less closely on to others. Five factors were replicated from the content map: monitoring, distraction, family presence, meal and snack schedule, and indulgence. However, unlike the content map, food availability and food accessibility loaded together and instead separate factors for healthy foods and unhealthy foods emerged for these two constructs. Similarly, modelling was also divided into the factors of healthy and unhealthy modelling. Three expected factors – neglect, limited or guided choices, and atmosphere of meals – were not well represented by the current items, suggesting either that the scales used in the present study did not adequately encompass these constructs or that parents do not respond to these as distinct. Finally, although a rules and limits subscale emerged, the items focused on rules about mealtime behaviour rather than rules about food per se. Table 5 shows subscale means, sd and Cronbach’s α values. Correlations among factors can be found in Table 6.

Table 5 Means and SD, Cronbach’s α values and test–retest reliability for all subscales within the Coercive Control, Structure and Autonomy Promotion domains

T1, time 1 (n 494); T2, time 2 (n 122).

* Indicates P <0·001.

Table 6 Bivariate correlations among Structure, Control and Autonomy Promotion domains of food parenting practices

* Indicates P <0·001.

The Structure subscales were significantly correlated with one another in expected directions (see Table 7). On average, parents reported high levels of healthy food availability and healthy modelling and low levels of less healthy practices (unstructured practices, distractions, unhealthy food availability and monitoring).

Table 7 Bivariate correlations between the subscales in the Structure domain of food parenting practices

Coercive Control

The concept map for Coercive Control included four factors (restriction, pressure to eat, threats and bribes, and using food to control negative emotions), with threats and bribes further broken down into three subscales (food-based threats and bribes to eat, food-based threats and bribes to behave, and non-food incentives to eat).

The factor analysis of the Coercive Control items yielded eleven factors. Of these, five closely corresponded with those proposed in the content map: pressure to eat, using food to control negative emotions, and the three subscales that form threats and bribes. In addition, restriction emerged as three separate scales: restriction for health, restriction for weight and covert restriction. Two additional Coercive Control scales emerged: punishment/harsh coercion and clean plate. Finally, an eleventh factor included only two items, which cross-loaded on the covert restriction scale, so they were included with that scale for the sake of parsimony, leaving ten factors.

Most of the Coercive Control subscales were positively correlated with one another, except for covert restriction and restriction for health, which were uncorrelated with using food as an incentive and to control the child’s emotions (see Table 8). On average, parents did not report high levels of Coercive Control. The highest subscale score was for restriction for health, with an average close to the midpoint of the 5-point scale (mean 3·34). Parents reported very low rates of restriction for weight control, using food to control their children’s negative emotions and punishment/harsh coercion.

Table 8 Bivariate correlations between the subscales in the Control domain of food parenting practices

Autonomy Promotion

The concept map for Autonomy Promotion included six constructs: nutrition education, child involvement, encouragement, praise, reasoning and negotiation. However, in the factor analysis, these items loaded on to seven factors.

In the current analyses, five of the constructs were mapped closely; however, a reasoning factor did not emerge. In addition, two constructs not in the concept map were evident in the data: responsive feeding and repeated offering.

All the Autonomy Promotion subscales correlated positively with one another (see Table 9) and parents reported moderate to high use of all these food parenting practices.

Table 9 Bivariate correlations between the subscales in the Autonomy Promotion domain of food parenting practices

Correlations

Correlations between the three broad constructs in the content map are shown in Table 6. A strong relationship emerged between the Structure construct and the Autonomy Promotion construct (r = 0·53). Coercive Control and Structure were negatively correlated (r = −0·19).

Additionally, correlations between subscales across constructs were computed; most were small to moderate (

![]() $\left| r \right|{\equals}0\!\cdot\!01\!-\!0\!\cdot\!47$

). However, some stronger relationships were found between subscales from Structure and Autonomy Promotion. Specifically, healthy availability was positively related to nutrition education (r = 0·58), encouragement (r = 0·61) and child involvement (r = 0·50). Healthy modelling was positively related to encouragement (r = 0·63) and nutrition education (r = 0·61). Finally, preparation was positively related to encouragement (r = 0·51), nutrition education (r = 0·56), child involvement (r = 0·58) and negotiation (r = 0·55).

$\left| r \right|{\equals}0\!\cdot\!01\!-\!0\!\cdot\!47$

). However, some stronger relationships were found between subscales from Structure and Autonomy Promotion. Specifically, healthy availability was positively related to nutrition education (r = 0·58), encouragement (r = 0·61) and child involvement (r = 0·50). Healthy modelling was positively related to encouragement (r = 0·63) and nutrition education (r = 0·61). Finally, preparation was positively related to encouragement (r = 0·51), nutrition education (r = 0·56), child involvement (r = 0·58) and negotiation (r = 0·55).

Test–retest reliability

Subscale means and sd at time 1, Cronbach’s α values at times 1 and 2, and test–retest reliability are given in Table 5. Test–retest correlations were compared with generally accepted standards( Reference Vaughn, Tabak and Bryant 8 ). Based on these standards, eight subscales demonstrated moderate test–retest reliability (r = 0·53–0·62) and sixteen subscales demonstrated strong test–retest reliability (r = 0·70–0·86).

Qualitative responses

Of items that received at least five open-ended responses, proportions of open-ended responses that indicated comprehension of the item ranged from 75 to 96 %. For a complete list of percentages of responses indicating understanding and samples of parents’ responses to open-ended questions, see Table 10.

Table 10 Sample responses from parents describing the last time they used a particular food parenting practice, and the percentage of qualitative responses that indicated comprehension of the items by subscale

Percentages are listed only for those subscales where at least half of the items received a sufficient number of follow-up responses (i.e. at least five responses per item).

Although the open-ended responses generally demonstrated that parents had a good understanding of the items, an examination of items demonstrating lower rates of comprehension (under 70 %) is illustrative. These items did not cluster on a single construct (one each from food to control negative emotions, food incentive to behave, food incentive to eat, punishment/harsh coercion, covert restriction, verbal encouragement and negotiation). However, several of these items relied on a specific temporal sequence (e.g. ‘I give my child an unhealthy food or drink if they promise to eat a healthy food later’) which might be too subtle for parents to respond to accurately on a survey (i.e. several parents were coded as not understanding the item if they gave an example of giving a child an unhealthy food after eating a healthy one).

Discussion

Using both qualitative and quantitative measures, the present study examined parents’ reports of their use of parental feeding practices for 2·5–7-year-old children as described in the conceptual framework presented by Vaughn and colleagues( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ). We measured twenty-eight dimensions across the parental feeding areas of Structure, Control and Autonomy Promotion. Our results provide insight into the extent to which and how parents are using these food parenting practices in their interactions with their children.

A great deal of the past research on food parenting has focused on subscales that are considered here as part of the Coercive Control construct. For example, restriction and pressure to eat are included in the widely used Child Feeding Questionnaire( Reference Birch, Fisher and Grimm-Thomas 20 ). Food incentives and using food to regulate children’s emotions have also received a lot of attention by researchers( Reference Blissett, Haycraft and Farrow 21 ). The current study added two additional subscales to this domain, which were not included by Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ): insisting that children clean their plate and punishment/harsh coercion. Because clean plate was one of the most highly endorsed Coercive Control subscales, and because the harsh coercion items are so severe in nature, both these subscales hold tremendous promise for understanding aspects of parental feeding that have not been well considered to date.

Less research has focused on the structural aspects of parental feeding practices. Recent research suggests that in addition to warmth and control, structure (e.g. clear and consistent rules, routines) represents a third major dimension of general parenting and is an important predictor of child outcomes( Reference Power 22 ). Similarly, available research supports the general finding that when parents create a healthy structure surrounding food (e.g. high availability of healthy foods, family meals together free of distractions), children show better dietary outcomes( Reference Andaya, Arredondo and Alcaraz 23 – Reference Taylor, Emley and Pratt 25 ). A recent study examining the structure component of this model found that structure-related feeding practices predicted child self-regulation in eating in children of pre-school age( Reference Frankel, Powell and Jansen 26 ).

The measures of the Structure subscales found here closely parallel those proposed by Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ). The primary exception was the finding that both modelling and availability separated into healthy and unhealthy subscales. For example, parents who reported keeping healthy foods in the house sometimes also reported keeping unhealthy foods in the house. Because dietary goals for children would include both increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables and limiting intake of nutrient-poor foods, looking at both unhealthy and healthy modelling and availability is important. Furthermore, although parents did report on rules, the content tended to differ from that proposed by Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ), who focused on rules about what, where, when and how much children should eat. The items included here focused primarily on rules for mealtime behaviour. Thus, this component might need further exploration, including expansion to examine eating behaviours outside mealtimes (i.e. snacking).

Perhaps the greatest contribution of the Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) framework is the inclusion of food parenting behaviours that promote autonomy in the eating behaviours of children. Although many parents are concerned with the short-term goal of getting their child to eat more healthy and fewer unhealthy foods, many would agree that teaching children to make lifelong healthy eating decisions for themselves is also important( Reference Moore, Tapper and Murphy 27 ). Thus, understanding and measuring how parents achieve this longer-term goal is imperative. Two subscales that emerged in the present study, which were not represented in the Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ) framework, were responsive feeding and repeated offering. In a review of thirty-one studies, Hurley et al. ( Reference Hurley, Cross and Hughes 28 ) report that the majority found significant associations between responsive feeding and lower child adiposity. Furthermore, a large literature base demonstrates that offering a novel food many times improves children’s acceptance and liking of that food( Reference Wardle, Herrera and Cooke 29 ).

Since the data here were collected, two additional advances have been made in the direction of mapping and measuring food parenting practices. First, O’Connor et al. ( Reference O’Connor, Mâsse and Tu 30 ) recruited a panel of experts to sort survey items into the constructs proposed by the framework used here. This sorting procedure yielded five Control clusters, nine Structure clusters and three Autonomy Promotion clusters. Meanwhile, Vaughn et al. ( Reference Vaughn, Dearth-Wesley and Tabak 31 ) offered a new measure, the HomeSTEAD, comprising five Coercive Control practices, twelve Structure practices and seven Autonomy Promoting practices. The empirically derived subscales were similar, though not identical, to those proposed in the concept map. For example, as in our data, a ‘clean plate’ subscale emerged in Vaughn et al.’s instrument, emphasizing its distinct relevance to parents, as differentiated from, for example, pressure to eat. Taken together, these studies reinforce the value of continuing to seek a convergence between top-down (expert driven) and bottom-up (data driven) approaches to understanding food parenting.

In addition to the quantitative findings here, a review of the qualitative data demonstrated that most parents put a great deal of thought and effort into feeding their children and desired to communicate this through examples. This was true even when the specific item did not apply to their individual situation. For example, in responding to the item asking for examples of ‘packing healthy foods in your child’s lunch/snacks for school’, parents whose children did not attend school provided examples of packing healthy snacks at other times when their child is away from home. Similarly, in responding to the item asking for examples of ‘helping your child set goals to eat more/new fruits and vegetables’, parent responses were enthusiastic about sharing methods to achieve this goal but infrequently included an example of specific, collaborative goal setting. However, these responses provide rich information that can contribute to our understanding of parent attitudes towards feeding and feeding practices. It was clear from these data that parents’ perspectives must be included in efforts to accurately capture food parenting.

The present study had several strengths. First, the research was driven by and the results aligned closely with the concept map for parental feeding proposed by Vaughn and colleagues( Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher 10 ). As such, the results present a strong framework within which to examine parental feeding practices. Second, unlike many existing approaches to food parenting that focus solely on negative feeding practices, the present study assessed both beneficial and detrimental feeding practices. The open-ended items showed that parents are engaging in many positive feeding practices, which suggests that if we hope to obtain a comprehensive and accurate understanding of how parents feed their children, assessing positive feeding practices is necessary. Third, although the sample is drawn only from individuals who use the crowd sourcing website, MTurk, the large, nationwide sample that included both mothers and fathers of children aged 2–7 years is likely representative of typical caregiver feeding practices. Furthermore, the current study is one of few studies on parent feeding that included fathers.

Although the study had several strengths, there are also a few limitations worth noting. First, the nature of the data is self-report, which means that it is subject to biases and mental errors. These reporting biases may be apparent in the low rates of endorsement for less socially desirable food parenting practices. The authors recommend that future research examining parenting practices uses observational data as well, and compares findings. Second, the measurement of these constructs could benefit from further improvement. For example, some subscales still demonstrate lower-than-preferred reliability and validity. Additional cognitive testing of the items would likely strengthen the measurement. Finally, food parenting is likely impacted by the parent–child relationship, child temperament and other dyadic factors. Future research should consider exploring the interactive nature of feeding occasions and how this contributes to parental feeding.

Despite these limitations, the results presented here contribute significantly to the understanding of caregiver feeding of children aged 2–7 years, and open the door to a multitude of future research projects. Although our sample was moderately large, it was limited to parents of 2–7-year-olds and parents and children were mostly Caucasian; therefore, future research would benefit from measuring food parenting in this way across other caregivers (e.g. grandparents, childcare teachers), child age ranges and cultures. Future investigation could also clarify how child weight, health parameters and health behaviours are related to parent feeding practices described in this framework. Similarly, more exploration of the bidirectional relationship between child factors and parent feeding is needed. A longitudinal or matched cohort study including both predictive and outcome factors would further illuminate the complex parental feeding–child outcome relationship.

Although the wide variety of instruments and conceptual approaches used in food parenting research has made it difficult to compare across studies, it has also provided opportunities to examine research questions from multiple perspectives. Ultimately, this might have encouraged progress in the field, which would not have been achieved had a single measure or model dominated the research. Nevertheless, as our understanding of food parenting has progressed, the widespread desire to frame and measure constructs in a more consistent, coherent and comprehensive way has become salient. While we do not imagine that this approach is the last that will be offered, it does begin the process of merging a concept map agreed upon by many experts in the field and empirically based perspectives. Thus, we hope that the results presented here will continue to move this collaborative discussion forward to inform future measurement and research in the important domain of food parenting.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: D.R.M.-E. oversaw all aspects of the study and the writing of the manuscript. L.G., L.R., J.M., M.T. and D.H. each contributed to the conceptualization of the study, the data collection and analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Bowling Green State University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.