Over the last two decades, the prevalence of obesity in women has increased dramatically, especially in middle-income countries( Reference Seidell 1 ) in which women are disproportionally affected by obesity. A variety of conditions are associated with obesity in women (including type 2 diabetes mellitus, CVD and breast cancer, among others)( Reference Field, Coakley and Must 2 ) that not only decrease their survival, but also compromise their current quality of life and reproductive health( Reference Nohr, Timpson and Andersen 3 ). Moreover, maternal obesity is an important risk factor for childhood obesity( Reference Durand, Logan and Carruth 4 ); thus, obesity in women has a multiplicative detrimental effect.

Chile, a post-transitional upper-middle-income Latin American country, has experienced a rapid epidemiological and nutritional transition( Reference Vio, Albala and Kain 5 ). The 2003 and 2010 National Health Surveys informed an obesity prevalence in women aged 25–44 years of 26·1 % and 28·3 %, respectively( 6 , 7 ). Although these data showed an increase in obesity, they were obtained from independent cross-sectional surveys; therefore, they do not reflect life-course BMI trajectories and do not provide information of the velocity of BMI changes. This information is relevant to identify critical periods of life in which to intervene, as well as to detect high-risk groups in which to target preventive interventions.

Presently, in Chile, as in several other countries, the public health-care system considers only secondary obesity preventive actions. Programmes are targeted to obese pregnant and elderly women and consider counselling and reductions in fat and sodium of the food products provided at primary health centres. The final goal is to avoid or delay the emergence of obesity-related metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Actions to prevent obesity or weight gain in the general population are not considered.

Since 2007, we have followed the mothers of a cohort of low- to middle-income pre-school Chilean children who participate in the Growth and Obesity Cohort Study (GOCS). In these women, we have obtained weight and height measurements at baseline and 3 years after, allowing us to assess the magnitude and velocity of BMI changes in Chilean women of reproductive age. We have also evaluated whether this trend varies according to age, socio-economic status (SES), parity and nutritional status in order to identify potential groups in which to target preventive actions.

Experimental methods

Study design and participants

The present study is a longitudinal analysis of the mothers of GOCS participants; objectives and methods of GOCS have been described elsewhere( Reference Corvalan, Uauy and Stein 8 ). Briefly, GOCS is a population-based ambispective cohort of 1195 children born in 2002 in six low- and middle-income counties from the south area of Santiago, Chile( Reference Kain, Corvalan and Lera 9 , Reference Corvalan, Uauy and Kain 10 ). The study sample is representative of the Chilean women resident in the Metropolitan Region (that concentrates 40 % of the total Chilean population) who receive care at the National Health Care Service System (low- and middle-income Chilean population, which is nearly 70 % of the entire population( 7 , 11 ); ethnic minorities are less than 5 % of the total)( 12 ). In 2007, 1165 mothers of the GOCS children (baseline: mean age = 32·0 (sd 7·0) years) were included in a longitudinal study of breast cancer risk factors; 805 were re-contacted in 2010 (follow-up rate = 69 %). Exclusion criteria for the present analysis were (i) concurrent pregnancy and (ii) delivery within the last year, to avoid weight change associated with pregnancy and breast-feeding (n 35). We further excluded nine women who were underweight at baseline because of the possibility of co-morbidities or eating disorders; therefore, the final sample total was 761 women.

Procedures

At baseline and follow-up weight and height were assessed by two trained nutritionists. Weight was measured using a SECA balance platform (Madison, WI, USA), in increments of 0·1 kg. Height was measured in increments of 0·5 cm using the height rod mounted to the scale, with the participant standing and dressed in light clothing without shoes. BMI (weight (kg)/height2 (m2)) was used to classify women in categories according to the WHO classification: normal weight (BMI = 18·5–24·9 kg/m2); overweight (BMI = 25·0–29·9 kg/m2); and obese (BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2)( 13 ). At baseline, age, years of education (<12 years v. ≥12 years, corresponding to secondary education completeness) and parity (number of biological children) were collected using a structured questionnaire. Parity was also assessed at follow-up (number of childbirths since 2007). Age and parity were categorized in groups based on the sample distribution. Changes in weight, BMI and parity were computed (2010 minus 2007 measurements).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis was carried out after evaluating normal distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables, were calculated. We also computed 95 % confidence intervals for descriptive statistics. BMI changes by age, education, parity and nutritional status subgroups were tested using the t test and ANOVA (with the Scheffé test for multiple comparisons); differences in obesity prevalence were evaluated with the χ 2 test. We evaluated the influence of age, education, baseline nutritional status (normal weight as reference) and parity on BMI change through linear regression crude and adjusted models. The coefficients of these models are interpreted as follows. For continuous variables (age, baseline parity and change in parity), β coefficients indicate the amount of BMI change (positive or negative) resulting from a one-unit increase in the predictor. For categorical variables (education and nutritional status), β coefficients indicate the amount of BMI change of a particular category compared with the reference category; thus, negative numbers indicate that BMI change was lower than in the reference group. In order to compute predictors of obesity prevalence and incidence, crude and adjusted (age, education, baseline parity and change in parity) logistic and binomial models were used, respectively. With logistic models we obtained prevalence odds ratios and with binomial models we estimated relative risk. P ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using the STATA statistical software package version 11·2.

Ethical aspects

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology, Universidad de Chile. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Comparisons between those contacted at 3 years (n 805) and those lost to follow-up (n 360) showed no differences between the two groups with respect to the following baseline characteristics: age (mean = 31·9 (sd 7·0) v. 31·0 (sd 6·8) years), BMI (mean = 27·1 (sd 5·1) v. 27·1 (sd 5·2) kg/m2), proportion having ≥12 years of education (65·0 v. 63·4 %) and baseline parity (mean = 2·1 (sd 1·1) v. 2·1 (sd 1·2) children; all P > 0·05; data not shown).

Final sample size after excluding pregnant (n 35) and underweight women (n 9) was 761. At baseline, mean age was 32·0 (sd 7·0) years (range = 18·6–50·0 years) and 61·0 % of women had BMI ≥ 25·0 kg/m2 (35·1 % overweight; 25·9 % obese); most of them had ≥12 years of education and on average they had 2·2 children (Table 1).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 761 low- to middle-income Chilean women of reproductive age, 2007

†Values are presented as mean and standard deviation.

After follow-up (3 years), women on average increased their BMI (mean = 1·1 (sd 2·2) kg/m2), but the changes were significantly higher in women aged <30 years than in women aged ≥30 years (1·4 v. 0·8 kg/m2), in those with normal baseline nutritional status (1·4 v. 0·6 kg/m2 in obese) and in women with one or more childbirths during follow-up (1·8 v. 1·0 kg/m2; all P < 0·01; Table 2).

Table 2 Change in BMI in 761 low- to middle-income Chilean women of reproductive age, 2007–2010

†P value for comparison of mean BMI change from baseline to follow-up (t test or ANOVA with Scheffé test for multiple comparisons).

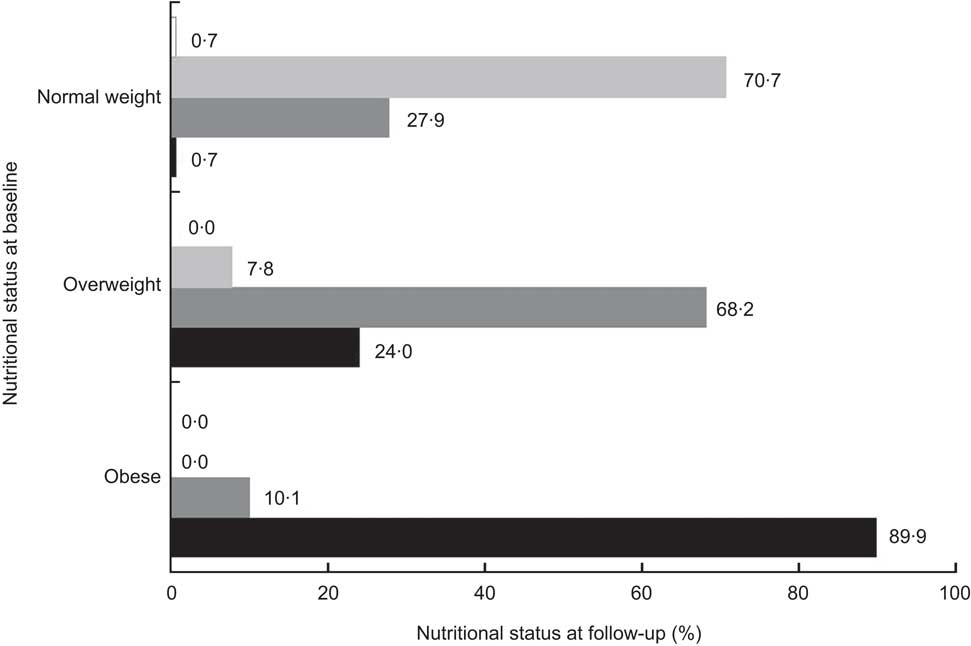

Almost a third (28·0 %) of normal-weight women became overweight and one out four (24·0 %) overweight women became obese; overall obesity increased by 23·4 % (Fig. 1). Total obesity cumulative incidence was 11·7 %. The increase in obesity was two times higher in less educated women (9·0 % v. 4·3 %, P = 0·009) and in those who had one or more childbirths during follow-up (11·6 % v. 6·0 %, P = 0·032; Table 3).

Fig. 1 Change in nutritional status between baseline (2007) and follow-up (2010) among 761 low- to middle-income Chilean women of reproductive age. Normal weight defined as BMI = 18·5–24·9 kg/m2 (n 297 at baseline), overweight as BMI = 25·0–29·9 kg/m2 (n 267 at baseline) and obesity as BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2 (n 197 at baseline); at follow-up, ![]() indicates prevalence of underweight (defined as BMI < 18·5 kg/m2),

indicates prevalence of underweight (defined as BMI < 18·5 kg/m2), ![]() indicates prevalence of normal weight,

indicates prevalence of normal weight, ![]() indicates prevalence of overweight and

indicates prevalence of overweight and ![]() indicates prevalence of obesity

indicates prevalence of obesity

Table 3 Change in obesity prevalence (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in 761 low- to middle-income Chilean women of reproductive age, 2007–2010

†P value for proportion comparison of change in obesity prevalence from baseline to follow-up (χ 2 test).

When assessing the relationship between BMI change and age, education, nutritional status, parity and change in parity, the multivariate model showed that only change in parity was positively associated with BMI increase. On the contrary, obese women at baseline had a lower increase in BMI compared with women with normal nutritional status (Table 4).

Table 4 Relationship between BMI change during follow-up and baseline nutritional status, parity, education and age, in 761 low- to middle-income Chilean women, 2007–2010

Ref., reference category.

Significantly different compared with the value for normal nutritional status: **P < 0·01.

†Regression coefficients from linear regression models.

Multivariate analyses showed that obesity prevalence at follow-up was positively associated with higher age (OR = 1·05; 95 % CI 1·03, 1·08). Nevertheless, obesity cumulative incidence was associated only with increased parity (RR = 1·53; 95 % CI 1·21, 1·90; Table 5).

Table 5 Relationship between obesity prevalence/incidence and parity, education and age in 761 low-to middle-income Chilean women, 2007–2010

RR, relative risk.

*Significant relationship: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†Exponentiated coefficients from logistic regression models for obesity prevalence or binomial regression models for obesity incidence (OR and RR).

‡≥12 years of education is the reference category.

Discussion

In women of reproductive age from a post-transitional Latin American country we observed an increase in BMI of 1·1 kg/m2 (equivalent to 2·6 kg) over a 3-year period. This increase is alarming given that it has been shown that modest increases in weight (even within the normal weight range) can increase metabolic (type 2 diabetes) and cardiovascular risks (hypertension and coronary risk)( Reference Willett, Dietz and Colditz 14 ). Moreover, we found that this increase is taking place in all women, independently of their age, education, parity or baseline nutritional status, indicating that the entire population of low-income urban women of reproductive age is at risk of excess weight. In this brief period of time, nearly a third of women with normal nutritional status became overweight while one out of four overweight women became obese.

Few longitudinal studies have evaluated individual weight trajectories in large populations. Studies carried out in developed countries have found smaller weight gain increases than what we observed in this population of low- to middle-income women( Reference Mozaffarian, Hao and Rimm 15 – Reference Rosell, Appleby and Spencer 17 ). The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study reported similar annual weight gain in Afro-American women, but in contrast to our results weight gain occurred mainly in women with excess weight( Reference Lewis, Jacobs and McCreath 18 ).

In the present study, adjusted models showed that increase in parity during the study period was positively associated with weight gain; for each childbirth BMI increased on average by 0·5 kg/m2 (equivalent to 1·2 kg). Several studies have reported that in transitional and developed countries, parity increases BMI( Reference Harris, Ellison and Holliday 19 , Reference Wolfe, Sobal and Olson 20 ). Longitudinal studies have shown that for each new child there is a weight increase of 2 to 3 kg after 6 to 12 months postpartum, but it decreases to 0·5 kg after 1·5 years( Reference Gunderson and Abrams 21 ); thus, our results are in line with what has been reported previously.

The literature shows that SES is one of the main underlying risk factors for obesity. In women from transitional countries obesity initially starts in high-income women and then extends to the rest of the population, becoming more prevalent in low-SES groups at the end of the nutrition transition( Reference Monteiro, Conde and Popkin 22 ). In our study we used education as a SES proxy and collected information in categories based on the Chilean educational system; in Chile, it has been shown that schooling below 12 years is associated with lower income( 23 ). We found a suggestion that women with lower education were at increased risk of obesity, although this association was no longer significant when taking into account other potential determinants (age and parity). Nevertheless, we believe that these results should be interpreted with caution because our sample was relatively homogeneous in other SES indicators (i.e. income, assets, etc.); further studies should clarify this relationship.

The present results indicate that at this age all women, and not only those who have excess weight, are at risk of rapidly gaining weight. Since weight gain is by itself a risk factor for obesity and other chronic diseases( Reference Must, Spadano and Coakley 24 , Reference Colditz, Willett and Rotnitzky 25 ), these results provide information to support the development of public policies to ensure healthy weight not only in specific risk groups but in all women. Population-based strategies should be defined based on their proved effectiveness for preventing weight gain or promoting weight loss and should include actions such as regulation of trans-fatty acids, promotion of breast-feeding and physical activity, ‘healthy’ urban design and specific taxes for unhealthy food, among others. Moreover, our results indicate that a key component of these policies should be avoiding excessive weight gain in pregnant women, even if they are of normal nutritional status. Ensuring a healthy weight during pregnancy has proved to have a protective role on long-term weight gain and has multiple benefits not only for mothers but for children as well.

Our results should not be extrapolated to the entire population of women in Chile as our sample was representative only of low- and middle-income women (70 % of total Chilean population); it is likely that the nutritional status of high-income women is ‘healthier’ than the one observed in this sample. Nevertheless, our results are informative because our sample represents the vast majority of the women of reproductive age who receive care in the public health system( 7 , 11 ). The intention of the present study was not to assess thoroughly all risk factors associated with weight increase, but to evaluate relevant factors in women at this age that could help in the identification of specific groups in which to target preventive public health policies.

The present study has several strengths. First, weight and height were measured following strict procedures with high quality standards; hence, we could directly assess the nutritional status of women and avoid under-report or misclassification. Second, all relationships were assessed prospectively, thus eliminating a potential recall bias.

Conclusion

We showed in reproductive-aged women from a country facing advanced stages of the nutritional transition that obesity is increasing at an alarming rate, much faster than what has been observed in developed countries. Urgent actions are needed in order to halt this epidemic and decrease the impact that this disease and it complications cause in several areas of the society (health, economy, etc.). Our results indicate that these actions need to be aimed at the population as a whole rather than targeted to specific sub-populations. A key component of these policies should be promoting weight control during pregnancy in all women irrespective of their pre-conception nutritional status. Achieving this goal should benefit not only women, but also the short- and long-term health of their offspring.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was supported by The Chilean National Science and Technology Fund (Fondecyt), projects 1090252 and 11100238. C.C. received a Wellcome Trust Training Fellowship. Conflicts of interest: All authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authors’ contributions: J.K., R.U. and C.C. conceived and designed the GOCS study. J.K. and M.L.G. applied for the funding. M.L.G., F.T.A. and C.C. conceived the present manuscript. M.L.G. and F.T.A. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all GOCS study participants and acknowledge the contribution of all GOCS staff and the team of fieldworkers at the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology, Universidad de Chile, especially Daniela Gonzalez and Angela Martinez.