Introduction

Cognitive models of psychosis suggest that dysfunctions in decision-making are involved in the formation and maintenance of positive states of psychosis (Garety & Freeman, Reference Garety and Freeman1999). In this process, which has been described as jumping to conclusions (JTC), individuals appraise ambiguous stimuli and come to a conclusion based on limited information, which in turn may result in delusional experience (Freeman & Garety, Reference Freeman and Garety2014). Over the past decades, numerous studies have investigated JTC bias in relation to psychosis, including clinical (Garety et al., Reference Garety, Freeman, Jolley, Dunn, Bebbington, Fowler and Dudley2005; So et al., Reference So, Freeman, Dunn, Kapur, Kuipers, Bebbington and Garety2012) and non-clinical samples (Freeman, Pugh, & Garety, Reference Freeman, Pugh and Garety2008), and different levels of psychosis expression (subthreshold, clinical) (Broome et al., Reference Broome, Johns, Valli, Woolley, Tabraham, Brett and McGuire2007). Several meta-analyses have been conducted, including many studies, examining the overall strength and specificity of JTC bias in psychosis (Dudley, Taylor, Wickham, & Hutton, Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016; McLean, Mattiske, & Balzan, Reference McLean, Mattiske and Balzan2017; So, Siu, Wong, Chan, & Garety, Reference So, Siu, Wong, Chan and Garety2016). Meta-analysis has revealed that JTC bias is consistently associated with psychosis and that the strength of the association is considered to be moderate (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016; McLean et al., Reference McLean, Mattiske and Balzan2017; So et al., Reference So, Siu, Wong, Chan and Garety2016). Compared with healthy controls, patients with psychosis use significantly less information in reaching a decision and show a stronger tendency of extreme responding (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016). Furthermore, the association between JTC seems to be primarily related to psychotic states, as associations with JTC bias in patients with non-psychotic mental disorders are weaker (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Mattiske and Balzan2017) and highly heterogeneous (So et al., Reference So, Siu, Wong, Chan and Garety2016). Moreover, the association between JTC appears to be delusion-specific, as people with psychotic illness with a higher level of delusional ideation show greater JTC bias than those with no delusional ideation (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016; Ross, McKay, Coltheart, & Langdon, Reference Ross, McKay, Coltheart and Langdon2015). Although there is some evidence that the association between JTC and psychosis is stronger in individuals with evidence of current symptomatology (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016), the question whether JTC bias is a trait or a state characteristic of psychosis remains to be elucidated. Given that healthy participants without psychosis show a degree of JTC bias, albeit to a lesser extent than patients, and that JTC bias is observed in patients without delusions, JTC bias appears to be neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause in the formation of delusions. In addition, the factors that contribute to JTC bias remain to be elucidated. One study investigated familial risk to psychosis as a possible contributing factor to JTC bias (Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006). In this study, JTC bias was examined in four groups with different levels of psychosis liability: (i) 40 patients with a history of non-affective psychosis, (ii) first degree relatives of patients with a history of non-affective psychosis, (iii) participants scoring high (>75th percentile) on the positive dimensions of psychosis proneness (measured with the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences, CAPE) (Konings, Bak, Hanssen, van Os, & Krabbendam, Reference Konings, Bak, Hanssen, van Os and Krabbendam2006) – see under ‘Instruments’ for a description of the questionnaire), (iv) healthy controls scoring in the average range (40th – 60th percentile on the CAPE). JTC was assessed using the beads tasks and JTC bias was defined as requesting only a single bead before deciding (see under ‘Instruments’ for a description of the task). A significant dose-response relationship was found between the level of psychosis liability (group) and JTC, and the association was conditional on the presence of delusional ideation (a dichotomized score on the delusion subscale of the Present State Examination, PSE) (Wing, Cooper, & Sartorius, Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974). These findings suggest that JTC is in part a trait associated with liability for psychosis, but also a state-related phenotype, given its specific association with delusional ideation. The current study aimed to replicate the findings from the study by Van Dael et al. (Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006), now using a much larger study sample. The aim of this study was to (i) investigate the association between JTC bias and familial liability for psychosis, using the status of non-affected sibling of a patient with the psychotic disorder as a marker of familial risk, and (ii) investigate whether any association with sibling status was specific for subthreshold delusional but not hallucinatory states.

Materials and methods

Participants

The EUGEI project is a 25-centre, 15-country, EU-funded collaborative network studying the impact of genetic and environmental factors on the onset, course and neurobiology of psychosis spectrum disorder (van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid, & Delespaul, Reference van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid and Delespaul2019). WorkPackage 6, ‘Vulnerability and Severity’, focused on the psychometric expression of genetic and environmental liability in the siblings of patients, who are at higher than average genetic and environmental risk compared to well healthy comparison participants. The sample in WorkPackage 6 was collected in Spain (five centres), Turkey (three centres), and Serbia (one centre) and consisted of 1525 healthy comparison participants, 1261 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder (average duration of illness since the age of the first contact with mental health services: 9.9 years) and 1282 siblings of these patients without a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Healthy comparison participants without a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder and without a sibling diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder were recruited from the general population. For a full description of the study see Guloksuz et al. (Reference Guloksuz, Pries, Delespaul, Kenis, Luykx, Lin and van Os2019) and van Os et al. (Reference van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid and Delespaul2019). Exclusion criteria for all participants were diagnosis of psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, history of head injury with loss of consciousness and intelligence quotient <70. To achieve high quality and homogeneity in clinical, experimental, and environmental assessments, standardized instruments were administered by psychiatrists, psychologists, or trained research assistants who completed mandatory on-site training sessions and online training modules including interactive interview videos and self-assessment tools (European Network of National Networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia et al., Reference van Os, Rutten, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, Viechtbauer and Mirjanic2014). Both on-site and online training sessions were repeated annually to maintain high inter-rater reliability throughout the study enrolment period (for details see: https://cordis.europa.eu/result/rcn/175696_en.html). The EU-GEI project was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of all participating sites and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013). All respondents provided written informed consent and, in the case of minors, such consent was also obtained from parents or legal guardian.

Instruments

Beads task

The most widely used task to assess JTC is the beads task in which participants are shown two jars containing green and red beads with equal but opposite ratios (85 red and 15 green beads and vice versa) (Huq, Garety, & Hemsley, Reference Huq, Garety and Hemsley1988; Phillips & Edwards, Reference Phillips and Edwards1966). Participants are informed of the proportions, and the jars are removed from view. One of the jars then is chosen, hidden from view, and a bead is drawn from it and shown on the screen to the participant. Beads are sequentially drawn and always replaced. Although the participants are told that beads are being selected randomly, the sequence of colours is predetermined according to the ratio of the two colours. Participants are then asked to decide whether the beads are drawn from the mainly green or the mainly red jar. In the condition used in this study, participants were free to determine how many beads were drawn, and the trial was terminated once participants confirmed they were certain about their choice. In this study, a computerized version of the beads task by Phillips & Edwards (Reference Phillips and Edwards1966) was used. In order to assess jumping to conclusions, JTC bias was defined as deciding after only a single bead was drawn (see under ‘analyses’).

General intelligence

Cognitive ability was estimated based on a short version of the WAIS-III short form: the Digit Symbol Coding subtest, uneven items of the Arithmetic subtest, uneven items of the Block Design subtest, every third item of the Information subtest (Blyler, Gold, Iannone, & Buchanan, Reference Blyler, Gold, Iannone and Buchanan2000; Velthorst et al., Reference Velthorst, Levine, Henquet, de Haan, van Os, Myin-Germeys and Reichenberg2013; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997). Conforming to our previous analyses we calculated, for each test, the Z-score, separately for each country and sex (van Os et al., Reference van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid and Delespaul2019). The cognition score was the mean of the Z-scores of the different tests, expressed as a T-score (cognition score shifted and scaled to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10), with higher scores representing better performance. The measure will be referred hereafter as ‘cognition score’.

Lifetime experience of positive psychotic experiences

The CAPE (www.cape42.homestead.com) was developed to rate self-reports of 42 items, of which 20 on lifetime psychotic experiences (Konings et al., Reference Konings, Bak, Hanssen, van Os and Krabbendam2006). Items are scored on a 4-point scale rating frequency of the experience.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out with STATA version 15 (StataCorp, 2017). A 3-level group variable was constructed reflecting the hypothesized order of psychosis risk strata, with controls (coded 0), siblings (coded 1) and patients (coded 2). The number of beads requested yielded a continuous variable within a range from 0 to 20. Based on the earlier work by Van Dael et al. (Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006) on the association between psychosis proneness and JTC bias, a variable was a priori constructed indicating whether there was a JTC bias, defined as requesting only a single bead before deciding (hereafter ‘JTC bias’) v. two beads or more before deciding. CAPE dimensions of the frequency of positive experiences (20 items) were included representing the person's positive psychotic experiences over the lifetime, hereafter ‘CAPE total positive score’. In line with earlier research investigating underlying dimensions of psychotic experiences measured with the CAPE (Wigman et al., Reference Wigman, Vollebergh, Raaijmakers, Iedema, van Dorsselaer, Ormel and van Os2011) lifetime presence of delusional experiences (based on 17 CAPE-items) was defined as the mean of all CAPE items on the delusions, paranoia, grandiosity and paranormal beliefs dimensions, hereafter ‘CAPE delusions’. ‘CAPE auditory hallucinations’ (based on 2 CAPE items) was calculated as the mean of CAPE items assessing lifetime auditory hallucinatory experiences. Likewise, ‘CAPE visual hallucinations’ was calculated (based on one item). Socio-demographic characteristics age (continuous variable), sex (0 = male, 1 = female), educational level (six levels, 1 = compulsory education no qualifications, 2 = compulsory education with qualifications, 3 = first level of non-compulsory education, 4 = vocational education, 5 = university undergraduate, 6 = university postgraduate) and cognition score were compared across groups using chi-square test (sex and group) and linear regression analyses (with group as independent variable and age, education level and cognition score, respectively, as dependent variable).

JTC bias and psychosis risk

Psychosis risk as a function of JTC bias was examined using multinomial logistic regression analysis. Effect sizes were expressed as relative risk ratio (RR) with their 95% confidence intervals. Post-estimation Wald test was used to compare relative risk estimates for siblings and patients. The following a priori selected confounders were included in the logistic regression model: age, sex, level of education (continuous variable) and cognition score. To adjust for any effects of country, country (three categories with Turkey as reference category) was entered in the model as well. In addition, standard errors were corrected for clustering of siblings and patients within the same family, using the Stata ‘cluster’ option.

JTC bias and delusions, auditory hallucinations and visual hallucinations

To investigate whether the association between JTC bias and psychosis risk was stronger with higher levels of CAPE delusions, the two-way interaction JTC bias × CAPE delusions was fitted in the multinomial logistic regression analysis. To test for specificity of any moderating effect of JTC and delusions on the outcome measure, the model was separately tested with the interaction JTC bias × CAPE auditory hallucinations and JTC × CAPE visual hallucinations.

Results

Sample

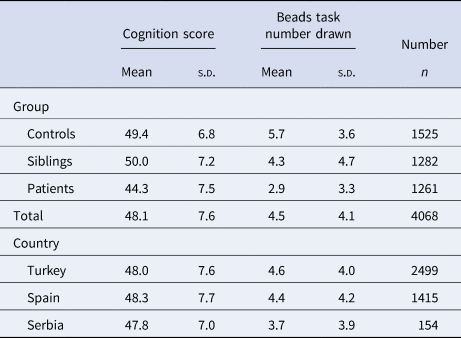

In total, 4068 participants were included, of which 1865 (46%) were female, with 1261 patients with a psychotic disorder (31% of the total sample), 1282 first degree siblings of the patients (32%), and 1525 controls (37%) (Table 1). There were no large or significant differences in age across the groups: patients, relatives and controls (β = −0.10, 95% CI = −0.48 to 0.28, p = 0.612). There were significant sex differences between the three groups (χ2 = 12287, df = 2, p < 0.001). Educational level was also significantly associated with the group (β = −2.45, 95% CI = −2.75 to −2.15, p < 0.001) and cognition score (β = −0.19, 95% CI = −0.24 to −0.14, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 1. Sample demographics by group and country

Note: s.d. = standard deviation, n = number of observations.

a Educational level: Level 1 = compulsory education no qualifications, Level 2 = compulsory education with qualifications, Level 3 = first level of non-compulsory education, Level 4 = vocational education, Level 5 = university undergraduate, Level 6 = university postgraduate.

Table 2. Cognitive scores by group and country

Note: s.d. = standard deviation, n = number of observations.

Association between JTC bias and psychosis risk

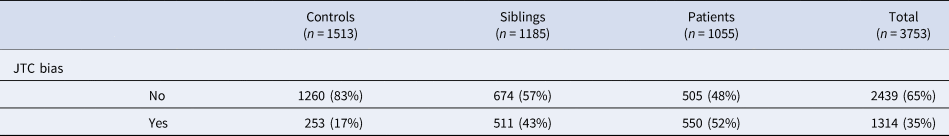

Overall, 35% of the participants displayed evidence of JTC bias: 17% of the control group, 43% of the sibling group, and 52% of the patient group (Table 3). Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed a significant association between JTC bias and psychosis risk (Table 4): both sibling status and patient status were associated with JTC bias, with the greater effect size for patient status (unadjusted association: RR = 3.78, 95% CI 3.16–4.51 for the sibling group compared to the control group and RR = 5.42, 95% CI 4.53–6.50 for the patient group compared to the control group; adjusted association: aRR = 4.23, 95% CI 3.46–5.17 for siblings and aRR = 5.07, 95% CI 4.13–6.23 for patients). The unadjusted RR was significantly greater for patients than for siblings (χ2(1) = 18.12, p < 0.001); and the same was the case for the adjusted RR (χ2(1) = 3.89, p = 0.049) .

Table 3. JTC bias per group

Table 4. Results (RR and 95% CI) on the association between JTC bias and psychosis risk outcome

Note: CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk ratio.

a Model adjusted for socio-demographics (age, sex, level of education, cognitive score, country and being a member of the same family).

Interaction between JTC bias and delusions

Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed a significant interaction between JTC bias and CAPE delusions, with an adjusted interaction term of 3.77 (95% CI 1.67–8.51) in the sibling-control model and a similarly directed but statistically imprecise aRR of 2.15 (95% CI 0.93–4.92) in the patient-control model (difference in interaction term siblings v. patients: χ2 = 3.06, df = 1, p = 0.08) (Table 5). The interaction between JTC and CAPE visual hallucinations was in the same direction but non-significant (aRR siblings: 2.28, 95% CI 0.71–7.35 and aRR patients: 1.39, 95% CI 0.58–3.35), with similar results for the interaction between JTC and CAPE auditory hallucinations (sibling group aRR: 1.63, 95% CI 0.37–7.08 and patient group aRR: 1.51, 95% CI 0.41–5.55).

Table 5. Results (RR and 95% CI) on the interaction between lifetime positive psychotic experiences and JTC bias on psychosis risk outcome

Note: CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk ratio.

a Model adjusted for socio-demographics (age, sex, level of education, cognitive score, country and being a member of the same family).

b Difference in interaction term siblings v. patients: χ2 = 3.06, df = 1, p = 0.08.

Discussion

The results show that patients with psychotic disorders, as well as their non-ill siblings, were more likely than controls to show a JTC bias. The association was furthermore contingent on evidence of delusional ideation, JTC being most strongly associated with sibling status if there was also evidence of delusional ideation. No such association was found for visual or auditory hallucinations. The results replicate earlier findings from the study by Van Dael et al. (Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006), in which JTC bias was similarly found to be associated with psychosis liability (i.e. patients and relatives showing the highest probability of JTC bias compared to healthy controls), and in which a similar interaction was observed between psychosis liability and evidence of delusional ideation in the model of JTC (Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006).

Methodological considerations

A strength of this study is that we followed a rigorous method, and strictly conformed to the procedure and sampling of the original study to achieve a true replication in a much larger and independent study population. Nevertheless, there are several methodological limitations that need attention. First, we investigated lifetime psychosis expression; and therefore, an inference based on the differentiation between lifetime and current symptomatology might be somewhat difficult to draw. However, the finding that non-ill first-degree relatives show greater JTC bias than controls, adds to the assumption that JTC bias may indeed represent a trait characteristic of psychosis. The study sample largely consisted of patients with an established diagnosis over a period longer than 5 years (average duration of illness since the age of the first contact with mental health services: 9.9 years); and therefore, our findings may not be entirely generalizable to earlier stages of psychotic illness. Second, the CAPE is developed to investigate psychotic experiences in the general population; therefore, ceiling effects might have occurred in the patient group. However, we should note that this would have caused an underestimation rather than an overestimation of the moderating effect of delusional ideation on the association between JTC bias and patient status. As patients are likely to experience more severe symptoms than assessed by CAPE self-report, this could also explain why the interaction term for the patients was imprecise. Third, we did not include specific cognitive measures to investigate whether JTC bias is a specific cognitive deficit or whether it reflects a more general cognitive impairment. Tripoli et al. (2020) investigated associations between JTC bias, psychosis and general cognition and found that case-control differences in JTC were mediated by IQ. The authors conclude that JTC bias may be a manifestation of a more general cognitive impairment rather than being a specific cognitive deficit associated with psychosis status. Although we did not calculate mediation effects, we adjusted for general cognition score and still found JTC bias to be significantly associated with the degree of psychosis liability. More research, however, is needed to clarify the specificity of the association between JTC bias (as opposed to other cognitive biases and general cognition score) and psychosis.

JTC and delusions

The results of this study suggest that the association between JTC and psychosis liability is specific for delusions (and not hallucinations). This was found not only in patients with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder but also in their first-degree relatives. Freeman similarly described such an association between JTC bias and delusion proneness in non-clinical individuals using a virtual reality experiment (Freeman, Pugh, Vorontsova, Antley, & Slater, Reference Freeman, Pugh, Vorontsova, Antley and Slater2010). So and Kwok (Reference So and Kwok2015) as well as Warman, Lysaker, Martin, Davis, and Haudenscheid (Reference Warman, Lysaker, Martin, Davis and Haudenscheid2007) however, did find evidence for an association between JTC and delusions in patients but not for JTC bias and delusion proneness in non-clinical samples. A recent meta-analysis concluded that JTC does covary with delusions across diagnoses and that JTC is not just associated with mental disorder in general. The association with delusions however, might be more specifically present at the more severe end of the continuum of delusional beliefs (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Mattiske and Balzan2017).

Longitudinal studies that examine the temporal dynamics of JTC and delusions are limited. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated whether JTC actually precedes the formation of delusions in healthy controls or individuals with above-average psychosis liability. Experimental studies manipulating JTC and examining the effects thereof on delusion severity have yielded mixed results thus far (Garety et al., Reference Garety, Waller, Emsley, Jolley, Kuipers, Bebbington and Freeman2015; Moritz, Veckenstedt, Randjbar, Vitzthum, & Woodward, Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Randjbar, Vitzthum and Woodward2011; Ross, Freeman, Dunn, & Garety, Reference Ross, Freeman, Dunn and Garety2011; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Brune, Bohn, Veckenstedt, Kolbeck, Krieger and Moritz2016).

Is JTC an endophenotype for psychosis?

Van Dael et al. (Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2006) found that JTC bias is present not only in patients with an established diagnosis of psychosis spectrum disorder but also in those with above-average (familial) liability for psychosis. The current analyses in a larger, multi-site sample confirm previous findings by showing that also unaffected family members have a higher degree of JTC bias than the general population. More evidence in support of the notion that JTC bias might be an endophenotype for psychosis comes from studies investigating JTC bias in the general population. These general population studies have revealed that JTC is more frequently present in individuals with prodromal symptoms of psychosis (Broome et al., Reference Broome, Johns, Valli, Woolley, Tabraham, Brett and McGuire2007) as well as in individuals scoring high on the CAPE (Lincoln, Lange, Burau, Exner, & Moritz, Reference Lincoln, Lange, Burau, Exner and Moritz2010) and other measures of subclinical delusional ideation (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Quilty, Zawadzki, Woodward, Sokolowski, Boon and Wong2013). Recently, JTC was found to be associated with co-occurring psychotic experiences and affective disturbances in a general population sample (but not with the sole presence of psychotic experiences nor affective disturbances), which suggests that JTC might contribute to the transdiagnostic phenotype of co-occurring psychotic and affective symptoms (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Rauschenberg, Ten Have, de Graaf, van Dorsselaer, Simons and van Os2019). Ludtke, Kriston, Schroder, Lincoln, and Moritz (Reference Ludtke, Kriston, Schroder, Lincoln and Moritz2017) investigated fluctuations in JTC bias over time using Experience Sampling Methodology and found JTC bias to be stably present in daily life, while fluctuations in JTC over the course of days also occurred. Moreover, fluctuations in JTC magnitude co-varied with psychosis expression. In conclusion, these findings replicate earlier findings that JTC bias is associated with familial liability for psychosis and that this is contingent on the degree of delusional ideation. Future studies are required to investigate the JTC bias longitudinally across the severity, continuity, and course of psychosis spectrum: acute v. remission, recent onset v. later stage and relatives v. controls.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients and their families for participating in the project. They also thank all research personnel involved in the EUGEI project, in particular G. Driessen. The EUGEI project was supported by the European Community's Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2009-241909 (Project EU-GEI). Dr O'Donovan is supported by MRC programme grant (G08005009) and an MRC Centre grant (MR/L010305/1). Dr Rutten was funded by a VIDI award number 91718336 from the Dutch Scientific Organisation. Drs Guloksuz and van Os are supported by the Ophelia research project, ZonMw grant number: 636340001.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.