Introduction

The South African response to coronavirus was swift and assertive in testing, tracing, and quarantining those infected with COVID-19 (Abdool Karim, Reference Abdool Karim2020; Ogbolosingha & Singh, Reference Ogbolosingha and Singh2020). Despite the rapid and effective public health response at the onset of the pandemic (South African COVID-19 Modelling Consortium, 2020), early evidence shows that the economic and social ramifications of the pandemic have disproportionately afflicted those already socioeconomically disadvantaged in a society defined by its racial and economic inequity (Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Davies, Gabriel, Harris, Makrelov, Robinson and Anderson2020). Furthermore, recent research shows that the harsh government sanctions to adhere to COVID-19 mitigation policies, including militarization, demolitions of informal settlements, and widespread police brutality, have impacted already vulnerable communities who are unable to properly quarantine (Isbell, Reference Isbell2020; Labuschaigne, Reference Labuschaigne2020; Staunton, Swanepoel, & Labuschagine, Reference Zhang and Ma2020). These measures bring focus to the existing disproportionate inequalities in common mental disorders that may be exacerbated by the rapid and dramatic societal changes brought by the pandemic and the countrywide lockdown.

The South African government imposed a strict ‘national lockdown’ policy on 26 March 2020 that prohibited citizens from leaving quarantine except for food, medicine, and essential labor. Worldwide, numerous aspects of life under forced confinement, including limited physical mobility, emotional distress, and for some, extreme threats to survival, are understood to pose major risks for mental distress and illness (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020). Studies on the mental health consequences of quarantine worldwide have reported marked increases in risk for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide (Jung & Jun, Reference Jung and Jun2020). For millions of South Africans, vulnerability to COVID-19 infection is amplified by other pre-existing adversities, such as hunger and violence, an overburdened healthcare system, a high prevalence of chronic and infectious disease, and alarming rates of poverty (55.5%) and unemployment (29%) (Docrat, Besada, Cleary, Daviaud, & Lund, Reference Docrat, Besada, Cleary, Daviaud and Lund2019; Joska et al., Reference Joska, Andersen, Rabie, Marais, Ndwandwa, Wilson and Sikkema2020; StatsSA, 2019).

Based on evidence from recent pandemics (e.g. SARS, MERS), poorer mental health status before quarantine is a major risk factor for worse psychiatric morbidity after quarantine (Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Yim, Song, Ki, Min, Cho and Chae2016; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Garay, Deamond, Moran, Gold and Styra2008). Recent estimates show that the prevalence, incidence, and burden of mental illness in South Africa are relatively high compared to other countries: one in three (30.3%) South Africans are expected to develop a mental illness, a quarter of all cases (25%) are considered severe, and nearly half of citizens (47.5%) are at risk of developing a psychiatric disorder in their lifetime (Herman et al., Reference Herman, Stein, Seedat, Heeringa, Moomal and Williams2009). Despite these conditions, mental healthcare usage and access in South Africa is severely limited, with only 27% of patients with severe mental illnesses receiving treatment, 16% of citizens enrolled in medical aid, and only 0.31 psychiatrist per 10 000 uninsured population (Docrat et al., Reference Docrat, Besada, Cleary, Daviaud and Lund2019). These severe barriers to care amidst high rates of mental illness emphasize the importance of prioritizing public mental health initiatives and increasing access to quality mental healthcare when considering the experience of and response to COVID-19 and future pandemics. The limited capacity of government public health initiatives and lack of research on disease burdens of COVID-19 highlight the urgent need for additional screening, treatment, and research efforts nationwide.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults residing in Soweto, a major township southwest of Johannesburg, during the South African lockdown of 2020. Specifically, our analyses examine the quantitative relationships between perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and depressive symptoms as well as qualitative perceptions of COVID-19 and mental health. During the first 6 weeks of the lockdown, which included the entirety of the strictest level of national restriction (i.e. Level 5), we conducted follow-up, mixed-method interviews with adults enrolled in an existing epidemiological surveillance study to assess the experiences of COVID-19 and adult depressive symptoms. To date, no study has empirically evaluated the mental health effects of COVID-19 experiences in South Africa.

Methods

Study setting

This research was nested within the Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit, which is part of the University of the Witwatersrand and located at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto, South Africa. Soweto is a low-income neighborhood within the expansive land-locked city of Johannesburg, South Africa, famous for its incorporation of six townships. Today more than one million people reside in Soweto and most are black South Africans, representing various ethnic identities (e.g. Xhosa, Sotho, etc.). Soweto is diverse economically, including middle-class neighborhoods, working class communities, and informal settlements. Residents report an elevated affliction of infectious conditions like HIV and TB and non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and depression. The prevalence of multimorbidity is high, which is compounded by costly health care services in the private sector and systemic barriers in the public sector.

Sample characteristics

All research participants were residents of Soweto and enrolled in a study preexisting the coronavirus pandemic. The first study was an epidemiological surveillance study of comorbidities, including mental (e.g. depression, anxiety), infectious (e.g. TB, HIV), and cardiometabolic diseases. All participants were 25 years or older and represented a wide range of ages and socioeconomic status (SES), though a majority of our sample were women (Table 1). Participants during Wave 1 of data collection, which took place between April 2019 and March 2020 were interviewed in their homes and provided informed consent. Participants were recruited based on a simple random sample of geographic coordinates within the boundaries of Soweto (n = 957). Wave 2 participants were followed up from this sample of 957 adults telephonically using mobile devices to prevent potential risk for COVID-19 infection – no in-person data collection was conducted. The University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Council reviewed and approved the study.

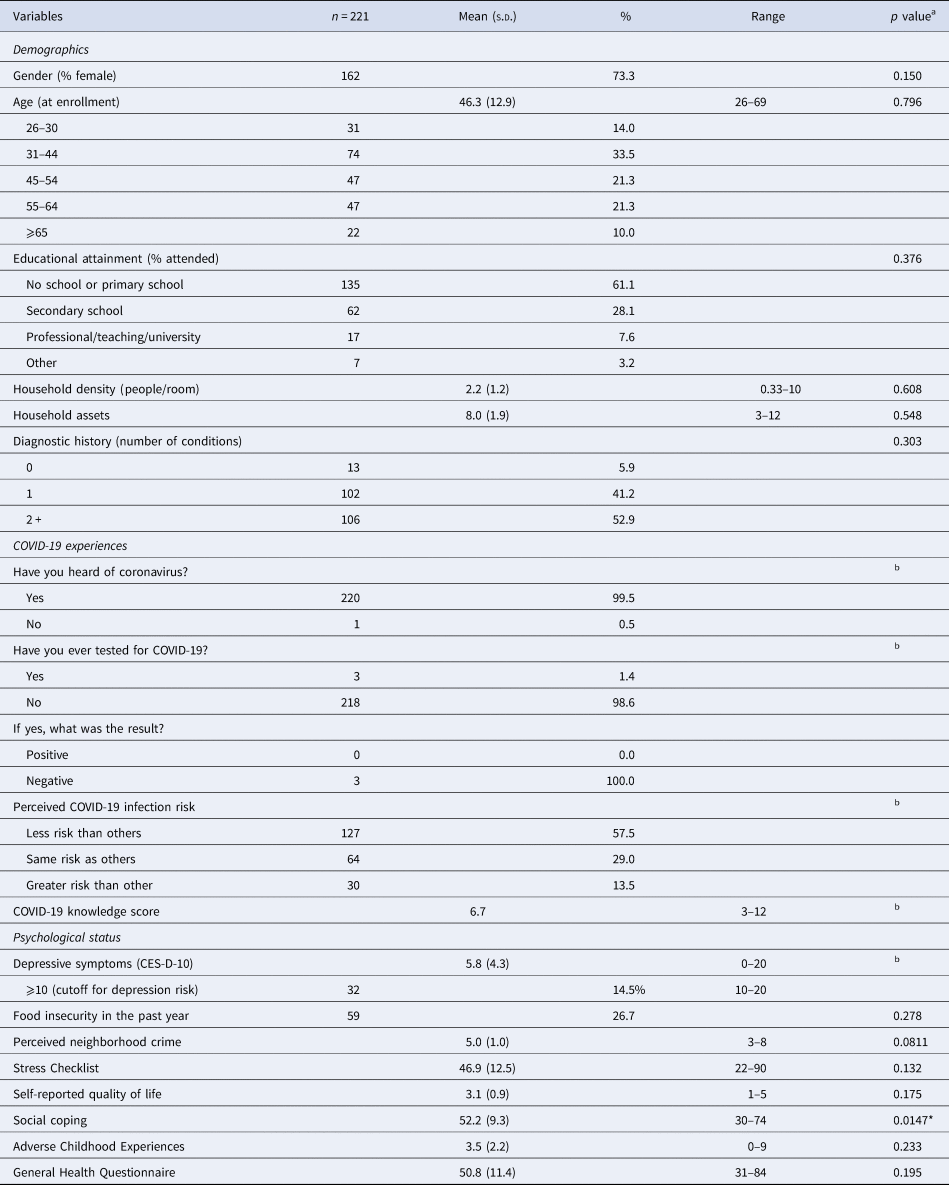

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, COVID-19 experiences, and psychological status

a Sample comparisons between Wave 1 and Wave 2 (follow-up) participants.

b No comparison available since this measure was only collected in Wave 2.

*p < 0.05.

Demographic, health, and socioeconomic variables

Wave 1 involved an extensive demographic survey which queried age, gender, household conditions, education, and disease history. Household SES was assessed using an asset index which scored participants according to the number of household physical assets they possessed out of 12 items, which was designed based on standard measures from the Demographic and Health Surveys (https://dhsprogram.com/). Food insecurity was assessed by asking whether household members experienced hunger in the past 12 months. Safety was assessed by summing two questions about how safe participants felt walking around their neighborhood during the day and night using a four-point Likert scale (very unsafe to very safe).

Psychological screeners

Wave 1

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) is a psychological screener that provides a measure of psychiatric risk based on four seven-item scales: somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression. The survey assesses changes in mood, feelings, and behaviors in the past 4 weeks. Individuals evaluate their occurrence on a four-point Likert scale. Seven questions are reverse scored and transformed before all responses summed. The internal consistency was 0.86.

We evaluated stress and coping through three scales; two were created based on previous ethnographic work (Kim, Kaiser, Bosire, Shahbazian, & Mendenhall, Reference Kim, Kaiser, Bosire, Shahbazian and Mendenhall2019; Mendenhall & Norris, Reference Mendenhall and Norris2015). First, the Soweto Coping Scale (SCS) was a 14-item measure that assessed various coping behaviors, ranging from individual psychological practices, family and peer support, and religious activities (Mpondo, Kim, Tsai, Norris, & Mendenhall, Reference Mpondo, Kim, Tsai, Norris and Mendenhall2020b). The SCS had an internal consistency of 0.71. Second, Soweto Stress Scale (SSS) (Mpondo, Kim, Tsai, & Mendenhall, Reference Mpondo, Kim, Tsai and Mendenhall2020a) was a 21-item measure that assessed the severity of contextual adversity due to personal concerns, interpersonal conflict, family strife, economic deprivation, community safety, and violence. The internal consistency was 0.80. This measure of contextual adversity was important to account for due to the heightened levels of violence and social adversity reported in Soweto (Richter, Mathews, Kagura, & Nonterah, Reference Richter, Mathews, Kagura and Nonterah2018). Third, the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACES) questionnaire retrospectively assesses experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Participants provide yes/no responses to queries about 10 distinct adverse events in their upbringing. Finally, we used the question, ‘how would you rate your quality of life?’ as a generalized measure of well-being. At the end of each interview, we offered resources for free telephone-based psychological counseling at a major mental health NGO in Johannesburg. Research assistants were encouraged to use these resources weekly due to potential psychological burden of data collection.

Wave 2

Wave 2 took place between late March and early May 2020. The 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale assesses major symptoms of depression – depressed mood, changes in appetite and sleep, low energy, feelings of hopelessness, low self-esteem, and loneliness. Respondents considered the presence and duration of each item/symptom over the past week and rated each along a four-point scale from 0 (rarely or never) to 3 (most or all of the time). Possible scores range from 0 to 30: a score of 10 and above indicates the presence of significant depressive symptoms. We found the CES-D had an internal consistency of 0.78.

COVID-19 experiences survey

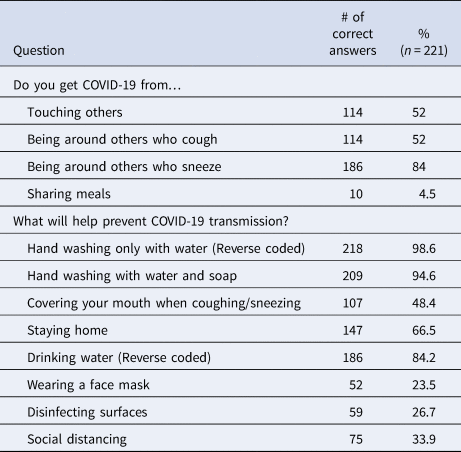

Wave 2 involved a mixed-methods survey that was created during the weeks prior to the national lockdown and administered telephonically. Lockdown conditions and the ongoing pandemic exacerbated ongoing structural and socio-economic barriers in Soweto, including electricity loss, telecommunication network failures, inability to pay for cellphone bills, larger economic constraints including under- and unemployment. Collectively, these constraints contributed to the overall loss to follow-up in Wave 2. Our COVID-19 experiences survey assessed awareness of COVID-19, COVID-19 infection status, and testing history. We assessed perceptions of COVID-19 prevention strategies, which asked whether a series of social and health behavior practices was understood to prevent and decrease the risk of infection (e.g. can you get infected by being around people who cough/sneeze, sharing meals; can you prevent transmission by wearing a face mask, social distancing, etc.) to which participants responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (Table 2). We summed the number of correct answers to create a composite measure of ‘COVID-19 knowledge’ (12 items). The internal consistency of the knowledge measure was 0.78. Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection was assessed by asking ‘Do you think you have the same risk as others?’ and responses included less risk, same risk, and greater risk than others. Less risk was assigned a value of 0, same risk was assigned a value of 1, and greater risk was 2. Because of the vast size and diversity within Soweto, further prompts specified participants to compare their risk relative to others living in their specific neighborhood in Soweto. Participants indicated whether they had less, the same, or more risk than others.

Table 2. Assessment of knowledge on COVID-19 transmission and prevention

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using version 15.1 of Stata (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). All variables were examined for normal distribution and outliers. Bivariate analyses were conducted between CES-D scores, perceived COVID risk, and covariates. With the exception of known psychological, household, and social factors that may confound the relationship between perceived COVID-19 risk and depression (Hamad, Fernald, Karlan, & Zinman, Reference Hamad, Fernald, Karlan and Zinman2008; Medrano & Hatch, Reference Medrano and Hatch2005; Myer et al., Reference Myer, Stein, Grimsrud, Herman, Seedat, Moomal and Williams2009; Nduna, Jewkes, Dunkle, Shai, & Colman, Reference Nduna, Jewkes, Dunkle, Shai and Colman2010), only those that were statistically significant at the 0.1 level during bivariate analyses were included in the final models. The following variables were included in the final model – gender, age, SES, household density (inhabitants/rooms), psychiatric risk (GHQ-28), childhood trauma, coping ability, contextual adversity, and self-reported quality of life. All covariates were assessed during the first wave of data collection. Food insecurity, safety, and chronic illness status were considered but removed because their associations were not significant at the 0.1 level. Additionally, we conducted a separate regression analysis to examine the predictors of perceived COVID-19 infection risk. Similarly, covariates considered for inclusion were identified from recent studies on COVID-19 risk perceptions (Kuang, Ashraf, Das, & Bicchieri, Reference Kuang, Ashraf, Das and Bicchieri2020; Kwok et al., Reference Kwok, Li, Chan, Yi, Tang, Wei and Wong2020; Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Sewpaul, Mabaso, Parker, Naidoo, Jooste and Zuma2020; Serwaa, Lamptey, Appiah, Senkyire, & Ameyaw, Reference Serwaa, Lamptey, Appiah, Senkyire and Ameyaw2020). These variables included gender, age, assets, household density, psychiatric risk (GHQ-28), coping, COVID-19 knowledge, and depressive symptoms (CES-D). Multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were conducted to examine the relationship between perceived COVID-19 and depressive symptoms and identify predictors of risk perceptions.

Qualitative analyses

Soweto is a diverse multilingual city where people may speak up to five different languages, and often there is an amalgamation of languages in everyday speech. Research staff conducted interviews in the preferred language of the study participant. However, they often read the question in English first and then repeated it in the preferred language if anything was unclear. Anything spoken in the vernacular was translated when they recorded responses in REDCap, a web-based database management software used for capturing and organizing all data collected in this study. Qualitative data on risk perceptions were cleaned and organized into responses (e.g. less risk, same risk, and greater perceived risk of COVID-19) and analyzed separately to identify reasons, experiences, and conditions that explained their risk perceptions. All data were organized and analyzed in Microsoft Excel.

Qualitative data on perceptions of COVID-19 and mental health were cleaned and then reviewed to identify common, emergent themes. Codes were then proposed, defined, and reviewed by the study team based on mutual agreement. Two coders, who were familiar with the social context in which this study was based, applied codes to the qualitative data. The coders analyzed 10 full interviews before their initial work was checked and compared against each other for quality control. The coders along with the senior author discussed the similarities and discrepancies for the first 10 interviews in order to standardize coding. Research assistants coded another set of interviews before meeting once more to discuss codes. The senior author oversaw and quality controlled the coding between the two coders and resolved any discrepancies. Afterwards, the research team convened to examine the qualitative data organized by codes, conduct axial coding based on major sub-themes, and summarize major trends in perceptions of COVID-19 and its impacts on mental health.

Results

Sample comparisons

Complete data on perceived COVID-19 risk, depression, and covariates were available for 221 adults (Table 1). Participants included in the analytical sample were similar to those excluded (n = 113) with respect to depression scores (CES-D-10), gender, age, assets, density, coping scores, contextual adversity, quality of life, psychiatric risk (GHQ-28), and adverse childhood experiences (p > 0.05). Perceived COVID-19 risk was significantly different from those excluded from the sample (p < 0.05). Adults in the analytical sample exhibited a higher perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Sample comparisons between Wave 1 and Wave 2 (follow-up) participants show no significant differences in all variables (p > 0.05) with exception to coping (p = 0.0147). The average coping score for Wave 1 participants lower relative to that of Wave 2 (follow-up) participants. Using the CES-D-10 cutoff score of 10, 14.5% of adults in our sample were at risk for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Qualitative perceptions and experiences of mental health and COVID-19

Table 3 shows the most common qualitative responses to the open-ended question, ‘How do you think COVID-19 affects the mindFootnote 1?’ We found that most people said ‘no’ (74%), COVID-19 does not affect the mind. Twenty percent indicated that COVID-19 causes what we coded as ‘anxiety’ reflected by ‘there is so much fear since it started, you hear the increase in numbers of infected people everyday, you have no idea when it will come near you.’ Other responses were ‘worries when it will stop,’ ‘fear and panic,’ and ‘fear of the future.’ Some indicated that the infection itself would cause mental distress (16%), such as ‘the virus is a scary thought’ and ‘I'm very afraid, being HIV positive I am very afraid of contracting corona because it might kill me.’ Next, many people described ‘thinking too much’ (10%), such as ‘coronavirus affects my mind because it is something that we are always thinking about.’ The ‘lockdown’ itself affected some (9%), such as ‘there are many restrictions’ and ‘most people around the area don't seem to be complying to the regulations.’ Some spoke of financial stress (8%), such as ‘we cannot make a decent money under lockdown restrictions’ and ‘no job brings in an income, food is now scarce.’ Other common responses addressed stress like ‘it has added more stress since there were a lot of issues to deal with, for example the lack of food for kids going to school.’ Other challenges reported independently and overlapping with these primary responses include sadness that you cannot socialize, family stress and death – including not attending a loved one's funeral, coping with the isolation of quarantine, and the chronic uncertainty of the days to come.

Table 3. Relative frequency distribution of qualitative data

Predictors of adult depression during COVID-19: longitudinal and cross-sectional relationships

Table 4 presents the results of the OLS regression analyses of demographic, household, psychological, and environmental factors that predict depressive symptoms. The unadjusted model (Model l) predicting CES-D scores on the cross-sectional measure of perceived COVID-19 risk displays a positive significant relationship (β = 1.6, p ≤ 0.001, 95% CI 0.79–2.34). This relationship between COVID-19 risk and depression remains highly significant after adjusting for gender, age, SES, and household density measured in Wave 1 (p ≤ 0.001) (Models 2–5). Models 6 through 11 examine the potential confounding effects of psychosocial experiences and behaviors in shaping the relationship between perceived COVID-19 risk and depressive symptoms. The effect of COVID-19 risk slightly weakens (β = 1.31, p = 0.001, 95% CI 0.53–2.08) after adjusting for past psychiatric risk assessed through the GHQ-28 during Wave 1, which is positively and significantly associated with CES-D scores (p ≤ 0.001) (Model 6). Adding childhood trauma into the model (Model 7) very modestly weakens the perceived COVID-19 risk coefficient (β = 1.30, p = 0.001, 95% CI 0.54–2.07). Social coping behavior from Wave 1 is inversely and insignificantly related to CES-D scores (p = 0.872) (Model 8). Model 9 and 10 show that self-reported quality of life during Wave 1 is negatively and significantly related to adult depression symptoms after the lockdown (p = 0.022), while contextual adversity during Wave 1 directly and insignificantly predicts CES-D scores. Model 11 includes COVID-19 prevention knowledge and shows that COVID-19 knowledge is positively and significantly related to CES-D scores (β = 0.04, p = 0.004, 95% CI 0.13–0.65). Including COVID-19 prevention knowledge into the model also strengthens the COVID-19 risk coefficient (β = 1.48, p ≤ 0.001, 95% CI 0.73–2.24).

Table 4. Multiple regression models of perceived COVID-19 risk predicting adult depression

† p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 5 displays results from regression models evaluating the predictors of perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Depressive symptoms (CES-D) (β = 0.05, p < 0.0001, 95% CI 0.022–0.068) was a significant, cross-sectional predictor of perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Past psychiatric risk (β = −0.048, p = 0.04, 95% CI −0.092 to −0.0023) and COVID-19 knowledge were (β = 0.01, p = 0.065, 95% CI −0.001 to 0.02) marginally significantly related to COVID-19 risk perceptions. Depressive symptoms and past psychiatric risk were positively correlated with greater perceived risk while greater COVID-19 knowledge predicted lower perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Gender, age, assets, density, psychiatric risk, contextual adversity, and coping did not predict perceived COVID-19 risk.

Table 5. Regression model of predictors of perceived COVID-19 risk

† p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

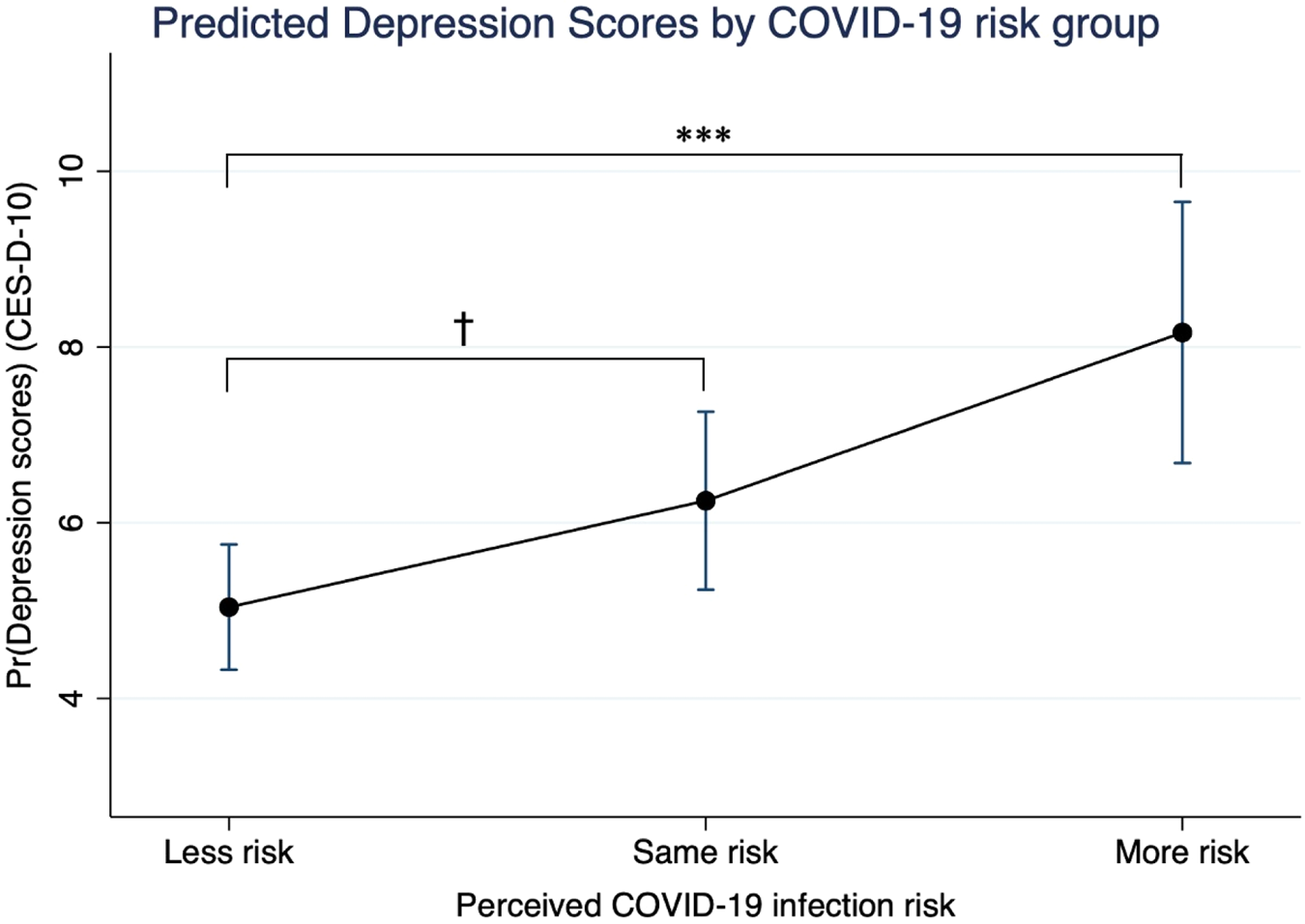

Figure 1 illustrates the positive relationship between perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and depression scores in our fully adjusted model: greater perceived risk of COVID-19 infection corresponds with greater depressive symptoms in our sample. Elevated psychiatric risk, childhood trauma, and a greater degree of COVID-19 knowledge were positive and significant predictors of worse depressive symptoms, while higher quality of life was inversely and significantly related. The fully adjusted model (Model 11) accounts for 21% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Additionally, a logistic regression of depression risk (using CES-D ⩾10 as a cutoff for significant depressive symptoms) on perceived COVID-19 risk with identical covariates estimated that the odds of the presence of significant depressive symptoms is 1.93 (p = 0.021; 95% CI 1.10–3.39) for every one unit increase in perceived COVID-19 risk (results not shown).

Fig. 1. Predicted depression scores by perceived COVID-19 risk group.

Note: Greater perceived risk of COVID-19 infection corresponds with greater depression symptomatology in adults living in Soweto. The effect of being in the ‘More risk’ group is highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) relative to being at ‘Less risk’, while the effect of perceiving that one is at the ‘Same risk’ of COVID-19 infection relative to other individuals living in Soweto on depression symptoms is marginally significant (p = 0.088).

Testing interactions between childhood trauma and COVID-19 risk perceptions

Finally, based on substantial literature on developmental theories that hypothesizes that greater early life trauma during child development sensitizes or potentiates future reactions to stress during adulthood and increases depressive risk (Heim, Entringer, & Buss, Reference Heim, Entringer and Buss2019; McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, Reference McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen and Gilman2010; Shapero et al., Reference Zhang and Ma2014), we hypothesized that greater childhood trauma would exacerbate the associations between perceived COVID-19 risk and depressive symptoms. We ran an interaction term (Model 12) between perceived COVID-19 risk and childhood trauma to examine whether early stress altered the association between perceived COVID-19 risk and depression. Model 11 shows evidence for a marginally significant crossover interaction between childhood trauma and perceived risk [F (1,208) = 3.51, p = 0.0625] and accounts for 23% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Figure 2 demonstrates that the depressive impacts of heightened perceived COVID-19 risk were greater among individuals who reported worse histories of childhood trauma, yet negligible in the low-risk group. The effects of psychiatric risk, COVID-19 knowledge, contextual adversity, and quality of life on CES-D scores were consistent. An identical logistic regression model showed that the interaction between childhood trauma and perceived risk was not significant, likely due to the non-linearity assumed in logistic models (Hellevik, Reference Hellevik2009).

Fig. 2. Childhood trauma (ACES) and Depression scores (CESD) by COVID-19 risk group.

Note: Greater childhood trauma (ACES) potentiates the positive relationship between greater perceived COVID-19 risk and the severity of depressive symptomatology. The effect of the interaction between childhood trauma and perceived COVID-19 risk on depression is marginally significant [F (1,208) = 3.51, p = 0.0625].

Discussion

The South African lockdown effectively prevented future COVID-19 infections and subsequent morbidity and mortality outcomes: epidemiological models suggest the lockdown resulted in a 40–60% reduction in transmission relative to baseline after 1 month (South African COVID-19 Modelling Consortium, 2020). The potential mental health consequences precipitated by the major societal changes from the lockdown, however, cannot be overlooked in a country with considerable psychiatric morbidity, limited mental healthcare infrastructure, and high rates of poverty and unemployment. Our findings highlight the depressive impacts of greater perceived COVID-19 infection risk and suggest that this relationship may be more severe among individuals with worse histories of childhood trauma. Additionally, our study re-emphasizes the importance of prioritizing and provisioning accessible mental health resources for resource-limited communities in Soweto and across South Africa.

Perceived COVID-19 infection risk and adult depression: cross-sectional and longitudinal perspectives

Our findings show that higher self-perceived risk of COVID-19 infection is cross-sectionally associated with greater depressive symptoms in our sample of adults living in Soweto. The association between perceived COVID-19 risk and depressive risk remained after controlling for recent psychiatric risk, quality of life, COVID-19 knowledge, stress, coping ability, and demographic factors. The direct relationship between higher risk perceptions and depressive risk reflects the growing body of global literature that illustrates the widespread mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (Pfefferbaum & North, Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020; Zhang & Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2020). Studies from China, Italy, and the USA show that perceived severity of the pandemic, psychological distress from COVID-19, and increased risk perceptions predicted poorer psychiatric outcomes (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Xu, Huang, Li, Lu and Xie2020; Li, Yang, Dou, & Cheung, Reference Li, Yang, Dou and Cheung2020; Rodriguez, Litt, & Stewart, Reference Rodriguez, Litt and Stewart2020; Simione & Gnagnarella, Reference Simione and Gnagnarella2020). The opposite may also be true – learned hopelessness and increased stress sensitivity characteristic of depression may lead to worse appraisals of stressful conditions, such as heightened perceptions of disease risk (Folkman & Lazarus, Reference Folkman and Lazarus1986; Luseno et al., Reference Luseno, Field, Iritani, Odongo, Kwaro, Amek and Rennie2020; Rovner, Haller, Casten, Murchison, & Hark, Reference Rovner, Haller, Casten, Murchison and Hark2014).

Greater public health knowledge of COVID-19 also corresponded with worse adult depression. The direct relationship between greater knowledge of COVID-19 prevention methods and depressive symptoms may reflect the adverse effects of being too cognizant, and potentially more fearful, of possible exposure to the many risk factors for COVID-19 infection (Huang & Zhao, Reference Zhang and Ma2020; Wang et al., Reference Zhang and Ma2020). These anxieties may be amplified in individuals who are knowledgeable of the COVID-19 risk factors but are unable to effectively prevent their risk for exposure. Numerous participants, for instance, noted that their neighbors and community members did not adhere to the lockdown restrictions or obligated to work in high exposure settings like grocery stores.

While the cross-sectional nature of our measures of perceived COVID-19 risk and depressive symptoms limits our ability to determine causal pathways that may precipitate these trends, our longitudinal evidence suggests that lower perceived quality of life, greater psychiatric morbidity, and an interaction between retrospectively-reported childhood trauma and perceived COVID-19 risk predict greater depressive symptoms in Wave 2. The inverse relationship between quality of life and future depressive symptoms is consistent with past literature (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Chen, Dewey, McCracken, Gilmore, Larkin and Wilson1999; Litzelman & Yabroff, Reference Litzelman and Yabroff2015). These results remained significant after controlling for pre-pandemic psychiatric morbidity, which was also a strong and expected predictor of future mental health status (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020).

We also report preliminary evidence that adults with more severe histories of childhood trauma may exhibit worse depressive symptoms due to greater COVID-19 risk perceptions during the first 6 weeks of lockdown (Fig. 2). The long-term impacts of childhood trauma on psychiatric risk and morbidity across the lifecourse are well-known (Mandelli, Petrelli, & Serretti, Reference Mandelli, Petrelli and Serretti2015). Furthermore, researchers have increasingly reported the stress potentiating effects of early life stress during adulthood (Bandoli et al., Reference Bandoli, Campbell-Sills, Kessler, Heeringa, Nock, Rosellini and Stein2017; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen and Gilman2010). Collectively, these bodies of work suggest that durable psychological effects of childhood trauma may explain the strong association seen between COVID-19 risk perceptions and adult depression.

Developmental pathways underlying perceived COVID-19 risk and adult psychiatric morbidity: possible mechanisms

We propose two possible pathways that may explain the stronger depressive effects of heightened perceived COVID-19 risk, and vice versa, in relation to childhood trauma. First, increased severity of childhood trauma may cause durable increases in psychological and physiological stress reactivity into adulthood and increase one's risk of developing MDD (Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, Reference Kendler, Kuhn and Prescott2004; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen and Gilman2010). A growing literature has documented that greater exposure to childhood trauma can alter the development of stress physiological mechanisms, such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation, the immune system, and brain function, and potentially increase both psychological and physiological reactivity to future stressors (Heim et al., Reference Heim, Entringer and Buss2019; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Krause, Barth, Myint, Weidinger, Stettinger and Schwarz2019; Oosterman, Schuengel, Forrer, & De Moor, Reference Oosterman, Schuengel, Forrer and De Moor2019). Recent evidence has also reported the long-term impacts of childhood maltreatment on brain regions, such as the amygdala (Dannlowski et al., Reference Dannlowski, Stuhrmann, Beutelmann, Zwanzger, Lenzen, Grotegerd and Lindner2012) and hippocampus (Opel et al., Reference Opel, Redlich, Zwanzger, Grotegerd, Arolt, Heindel and Dannlowski2014), which regulate the perceptions of threat appraisal and emotions (e.g. fear, sadness) and are involved in the pathogenesis of MDD (Teicher, Samson, Anderson, & Ohashi, Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016). These early life stress-linked alterations in stress physiology may subsequently predispose individuals to developing a suite of psychopathologies, including depression.

Conversely, greater past childhood trauma may increase the severity of adult depressive symptoms or MDD and increase emotional and biological sensitization to future stressors and adverse conditions. As previously discussed, childhood trauma is a well-known risk factor that influences the severity and duration of MDD and other psychopathologies (Kim, Adam, Bechayda, & Kuzawa, Reference Kim, Adam, Bechayda and Kuzawa2020b; Mandelli et al., Reference Mandelli, Petrelli and Serretti2015). Additionally, key symptomatic behaviors of MDD, such as persistent feelings of victimization, learned hopelessness and helplessness, and negative appraisal (Folkman & Lazarus, Reference Folkman and Lazarus1986; Peterson & Seligman, Reference Peterson and Seligman1983) likely motivate the elevated self-perception of COVID-19 infection risk. For example, previous research on perceived AIDS risk found that adult women with greater severity of childhood trauma reported increased perceptions of contracting HIV (Medrano & Hatch, Reference Medrano and Hatch2005). Adults with histories of childhood trauma and greater MDD severity, particularly among melancholic MDD patients, have shown to develop increased psychological (Peterson & Seligman, Reference Peterson and Seligman1983) and neuroendocrine (Stroud, Davila, Hammen, & Vrshek-Schallhorn, Reference Stroud, Davila, Hammen and Vrshek-Schallhorn2011) sensitization to future stressors. Thus, elevated perceived COVID-19 infection risk may arise as a function of the depressive effects from childhood trauma. Future longitudinal research is needed to determine the precise mechanisms by which childhood trauma, perceived COVID infection risk, and depressive symptoms are related.

Perceptions of mental health, COVID-19, and differential risk: qualitative insights

While most did not think that COVID-19 affected their mental health, we found a variety of stressors that caused deep worry, anxiety, and rumination (‘thinking too much’) in approximately 20% of adults. These constant foci during the lockdown were driven by the inability to care for themselves and their families, crippling financial concerns, vulnerability due to existing conditions, the invisible nature of COVID-19 transmission, and a lack of awareness of COVID-19. It is unsurprising that the same factors that motivated concerns over mental distress also impacted one's perception of their own risk of COVID-19, which highlights the coupling of perceived disease risk and depressive symptoms in our sample. The discordance between the highly prevalent perception that COVID-19 did not impact mental health and that a subset of the same individuals experienced anxiety, fear, and rumination is notable. This discrepancy may be motivated by varied conceptions of mental health, including mental health stigma. While participants believed that the pandemic did not affect their mental health (or their ‘mind’), the strong relationship between perceived risk and depressive symptoms, however, raises the concern that participants may not be aware of the potential threats to their mental health during COVID-19.

Few cases had been detected in Soweto during the first month of lockdown, although a portion of our sample perceived their risk as high and expressed deep anxiety and fear over personal and family well-being. Knowledge of COVID-19 prevention and depressive symptoms were significant and cross-sectional predictors of risk perceptions, while age, gender, SES, educational attainment, household density, coping ability, and whether people had heard of coronavirus did not significantly predicted risk perceptions. Our qualitative data suggest that inability to properly social distance and quarantine, potent psychosocial stress, preexisting health conditions, unemployment, and food insecurity may exacerbate already vulnerable families, placing them at greater risk of disease susceptibility. These results emphasize the importance of public health awareness campaigns, effective messaging around prevention, and the impacts of preexisting structural vulnerabilities on shaping COVID-19 infection risk. This finding also recapitulates the lessons learned from the HIV/TB epidemics in South Africa, that the fundamental causes of infectious disease must be systematically prioritized during public health responses. The current response to COVID-19 contrasts starkly to that of HIV/TB, which included scientific denialism and limited surveillance, research, and treatment. This history, however, informed the country's comprehensive and aggressive response to COVID-19 (Whiteside, Parker, & Schramm, Reference Whiteside, Parker and Schramm2020).

Methodological considerations for global mental health research in low- and middle-income contexts

While the social conditions and realities in this research context pose numerous research barriers that ultimately limit the strength of our analyses, the same barriers also result in the larger under-representation of studies in low- and middle-income and resource-constrained contexts in scientific and public health research. Unfortunately, these settings face the greatest burden of mental illness worldwide (Patel, Reference Patel2007; Vigo, Thornicroft, & Atun, Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun2016) and potentially COVID-19 (Hopman, Allegranzi, & Mehtar, Reference Hopman, Allegranzi and Mehtar2020) and its psychiatric sequelae (Subramaney et al., Reference Subramaney, Kim, Chetty, Chetty, Jayrajh, Govender and Pak2020). Representative samples in global mental health research provide an accurate portrayal of the larger target population's state of morbidity and psychosocial environment – without the implementation of costly, population-wide studies. As a result, public health and clinical teams can more confidently apply these data to inform future epidemiological research and design contextually-specific interventions and policies. The complex realities of epidemiological data collection in resource-limited and historically oppressed communities such as ours, however, pose numerous barriers for obtaining representative samples and proper measurements (Penrod, Preston, Cain, & Starks, Reference Penrod, Preston, Cain and Starks2003).

Long histories of scientific racism (Baldwin-Ragaven, London, & De Gruchy, Reference Baldwin-Ragaven, London and De Gruchy1999; Dubow, Reference Dubow1995), culture-biased psychometric testing (Stevens, Reference Stevens2003; Suffla & Seedat, Reference Suffla and Seedat2004), and distrust in medical research among black South Africans (Barsdorf & Wassenaar, Reference Barsdorf and Wassenaar2005) foreground our current research and may have dissuaded participants from enrolling in our follow-up study. Prior research on epidemiological sampling in Soweto also expressed distrust and concerns of confidentiality (Norris, Richter, & Fleetwood, Reference Norris, Richter and Fleetwood2007), particularly when discussing health issues in the presence of others in their homes (Draper et al., Reference Draper, Bosire, Prioreschi, Ware, Cohen, Lye and Norris2019) and telephonically. The nationally mandated quarantine order made the home environment even less private for participants to answer study questions, especially families living in crowded conditions.

Numerous compounding economic barriers, including persistent electricity outages, telecommunication network failures, unpaid cellphone bills, and general financial, strain also rendered some participants uncontactable through phone. Finally, COVID-19-related stress and trauma may have also discouraged participants from earnestly speaking about their views and experiences during the pandemic as conversations about COVID-19 or other household struggles may have been distressing or triggering. Given that our data collection was limited to the first 6 weeks of the lockdown during the most severe period of the national lockdown restrictions, these barriers along with the shortened timeframe ultimately limited our final sample size at follow-up. Collectively, these socioeconomic, material, and psychological adversities likely compromised our ability to sample hard-to-reach and resource-constrained households that were possibly most susceptible to the mental health impacts of the pandemic (Joska et al., Reference Joska, Andersen, Rabie, Marais, Ndwandwa, Wilson and Sikkema2020; Subramaney et al., Reference Subramaney, Kim, Chetty, Chetty, Jayrajh, Govender and Pak2020). Identifying accessible and efficient methods must be the priority for global mental health in order to increase the representativeness of data in such samples and ultimately, sustainable solutions for public mental health (Kim Reference Kim2020a; Patel, Reference Patel2007).

The relatively high levels of societal adversity in Soweto (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Mathews, Kagura and Nonterah2018) in addition to the stressors of the pandemic pose further complexities to our interpretation of the depressive impacts of infection risk and distress. These include poor construct validity, heightened risk for omitted variable bias, and the consideration of possible developmental effects. Furthermore, the overrepresentation of high-income, Western studies in research on global mental health (Stein & Giordano, Reference Stein and Giordano2015) and developmental psychology limit the generalizability of the existing literature to non-Western, low- and middle-income contexts where conditions of chronic stress, such as poverty, unemployment, and violence, across multiple levels of life are prevalent (Burns, Reference Burns2015; Fearon et al., Reference Zhang and Ma2017; Lund et al., Reference Lund, De Silva, Plagerson, Cooper, Chisholm, Das and Patel2011). Past studies have attempted to disentangle the compounded effects of lifecourse and contextual adversity on mental health by utilizing a combination of retrospective (or prospective, if available) and multidimensional measures of the social environment.

For example, in a cross-sectional cohort study of mental health among former child soldiers in Nepal, Kohrt and colleagues (Reference Zhang and Ma2008) account for a comprehensive range of trauma exposures (both witnessed and perpetrated), family conditions, and social adversities to account for complex and interacting effects of the numerous stressors and traumas faced by child soldiers. Additionally, Fearon et al. (Reference Fearon, Tomlinson, Kumsta, Skeen, Murray, Cooper and Morgan2017) prospectively account for multiple domains of adversities (e.g. developmental, individual, material, familial, household, community) between infancy and mid-adolescence to examine patterns of cortisol reactivity in a high-adversity, low-income settlement in the Western Cape, South Africa. We attempt to thoroughly account for the complex effects of both lifecourse and recent adversity on risk perceptions and depression by accounting for a range of stress-related measures childhood trauma, recent psychiatric morbidity, household crowding, SES, and COVID-19 awareness, in addition to an ethnographically-derived measure of psychosocial stress (based on 107 life history interviews) that assessed individual, interpersonal, household, and community adversity (Mpondo et al., Reference Mpondo, Kim, Tsai, Norris and Mendenhall2020b). Notwithstanding, longitudinal evidence, repeated measures of stress and mental health, and further data on the social conditions of the pandemic during Wave 2 would have allowed for the use of causal inference to elucidate pathways underlying the mental health impacts of COVID-19 risk.

While we have examined the effects of a variety of individual-level factors in relation to perceived infection risk and depressive symptoms, the social and historical contexts from which many of these social and psychological factors arise greatly influence the current state of psychiatric morbidity and vulnerability to infection in Soweto today (Barbarin & Richter, Reference Barbarin and Richter2013; Fassin, Reference Fassin2007). Nearly all participants were born during the oppressive apartheid regime or shortly after its violent dissolution, which is when all reported childhood traumas took place. Though children were not always exposed to the everyday adversities and extreme traumas of racial segregationist cultures and policies, the distributive impacts of racialized and classed violence among families often times translated to poor housing quality, food insecurity, family violence, and child abuse (Hickson & Kriegler, Reference Hickson and Kriegler1991; Lockhat & Van Niekerk, Reference Lockhat and Van Niekerk2000). The psychological, economic, and structural legacies of apartheid violence manifest in the present moment where the intergenerational trauma of apartheid may persist and sustain racial and class disparities in mental illness, socioeconomic opportunity, and infectious disease risk. We offer this history to contextualize our findings and emphasize the importance of prioritizing accessible mental health and infectious disease prevention services countrywide.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the mental health impacts of COVID-19 experiences during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic and national lockdown in South Africa. We report that the relationship between increased depressive symptoms and greater perceived COVID-19 infection risk was more severe among adults who reported worse histories of childhood trauma. Adults were two times more likely to experience significant depressive symptoms for every one unit increase in perceived COVID-19 risk. Greater knowledge of COVID-19 prevention and transmission was associated with lower perceived risk of depression but higher depressive symptoms. While a large majority of participants reported that experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their mental health (or ‘mind’), 10–20% of participants reported potent experiences of anxiety, fear, and ‘thinking too much’ as a result of the pandemic. Our results highlight the compounding effects of past traumatic histories and recent stress exposures on exacerbating the severity of depressive symptoms among adults living in an urban South African context.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to the participants, their families, and our research assistants as this study would not have existed without them. Specifically, we would like to thank Lindile Cele, Sbusiso Kunene, Gladys Morsi, Sharlotte Sihlangu, and Jackson Mabasa for their hard work calling our study participants during the early days of lockdown. We are also extremely grateful for the front-line and community health workers who are working endlessly to keep Soweto and the rest of South Africa healthy and safe.

Author contributions

AWK conceptualized the question, study design, and analysis, oversaw data collection, conducted quantitative data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. TN assisted with data cleaning and analysis and reviewed the paper. EM acquired funding for the parent study, designed the study protocol, oversaw and conducted qualitative data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript.

Financial support

The research was funded by a grant (1R21TW010789-01A1) to EM from the Fogarty International Center at the US National Institutes of Health. AWK is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW010543. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

None.