Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a potentially debilitating condition, characterized by persistent symptoms of intrusive re-experiencing, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, alterations in mood and cognitions, and heightened arousal and reactivity. In adults, higher rates of PTSD in females than in males have been consistently observed, with the estimated lifetime-prevalence being twice as high for females (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes and Nelson1995). Females also tend to exhibit greater overall posttraumatic stress symptom (PTSS) severity (Tolin and Foa, Reference Tolin and Foa2006). It has been hypothesised that the higher prevalence of PTSD in women may be a consequence of sex differences in neuroendocrine, hormonal and stress response systems, types of trauma experienced, coping strategies, and socialization (for reviews, see Olff et al., Reference Olff, Langeland, Draijer and Gersons2007, Garza and Jovanovic, Reference Garza and Jovanovic2017). Meta-analytic evidence based on cross-sectional data suggests that the relative risk of developing PTSS for females v. males increases with age at trauma exposure up until adolescence (Trickey et al., Reference Trickey, Siddaway, Meiser-Stedman, Serpell and Field2012). However, longitudinal study is required to gather more precise information about when such sex differences emerge during development.

Observations of age-related effects on sex differences in PTSS prevalence concord with findings for major depression, where higher rates are reported in females v. males from adolescence onwards (Wade et al., Reference Wade, Cairney and Pevalin2002). Evidence indicates that pubertal stage, rather than chronological age, may be a more reliable predictor of the latter effect (Angold and Costello, Reference Angold and Costello2006). In the PTSD field, it has similarly been hypothesised that hormonal changes associated with the onset of puberty (e.g. in adrenal androgens and sex steroids) could play a role in heightening female vulnerability to the effects of trauma, likely by influencing both general physiological systems such as neurotransmitter or stress systems, as well by interacting with the other sex specific vulnerability factors (Garza and Jovanovic, Reference Garza and Jovanovic2017). However, associations between pubertal timing and PTSS vulnerability have yet to be demonstrated.

In the current study, we conducted an analysis of sex differences in the prevalence of PTSS symptoms in a large longitudinal UK birth cohort. The longitudinal design included symptom assessments at 8, 10, 13 and 15 years, which allowed us to study the emergence of sex differences in PTSS from late childhood to adolescence within the same cohort. We also conducted a preliminary examination of potential contributors to sex differences. Specifically, we explored: (a) whether pubertal status contributes to the hypothesised emergence of sex differences in PTSD in adolescence and (b) whether the overlap with depressive symptoms would explain PTSD effects.

Methods

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a prospective birth cohort study, which recruited 14 541 pregnant women living in the geographic area of Avon, UK, with expected delivery dates between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Local Research Ethics Committees, and the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. With additional recruitment happening later, the enrolled sample for whom at least one assessment was completed consists of 15 589 children, resulting from 15 454 pregnancies. Data from the parents and these children have been collected on a regular basis since the child was born (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser, Henderson, Molloy, Ness, Ring and Davey Smith2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Davey Smith, Henderson, Macleod, Molloy, Ness, Ring, Nelson and Lawlor2013), and the ALSPAC study website provides a complete data dictionary and variable search tool (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/). The current study focuses on assessments completed during research clinics at 8, 10, 13 and 15 years. Informed consent for the use of data collected via questionnaires and clinics was obtained from participants following the recommendations of the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee at the time.

Materials

Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA)

The DAWBA provides a measure of DSM- and ICD-based diagnoses of all major psychiatric disorders for the ages 5–16, with established validity and reliability (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward and Meltzer2000). In ALSPAC, the DAWBA PTSD assessment was completed by the child's current carer (predominantly the biological mother), at clinic assessments at the ages 8, 10 and 13, and by the adolescents themselves at the age of 15. Participants were first given the screening question – ‘During your (child's) lifetime, has anything exceptionally stressful happened to you (them) that would really upset almost anyone, such as being involved in a terrible accident, or being abused, or some other sort of disaster?’. If this was answered affirmatively, the carer/adolescent was asked to provide details on the age at which the event had taken place, and whether the event had caused significant distress at exposure (1 = ‘yes’, 2 = ‘no’). Carers also rated associated past month PTSS in their child/adolescent at age 8, 10 or 13 years (13 items), and adolescents self-rated their PTSS at 15 years (15 items, due to two symptoms being added to the latest DAWBA version), on a scale of 0 = ‘no’, 1 = ‘a little’, or 2 = ‘a lot’. Responses were summed to create symptom scores of 0–26 and 0–30 points respectively. For the current analyses, we utilised two variables to capture PTSD symptom experiences: (a) the total symptoms score; (b) a binary variable indicating the presence PTSD symptoms, defined as at least one PTSD symptom being present ‘a lot’ over the past monthFootnote †Footnote 1. We also derived a second set of scores to capture ‘core’ PTSD symptoms that do not overlap with depression symptoms. For this, we recomputed our total symptom scores and binary variables excluding the five DAWBA PTSD items (7 items at 15 years) describing symptoms commonly also found in depression, such as reduced interest in activities, and trouble sleeping or concentrating, while retaining 8 items related to PTSD only, indexing, for example, intrusive re-experiencing or avoidance. This was done to check whether the well-established emergence of sex differences in depressive symptoms might be contributing to any PTSS effects as assessed via the DAWBA.

Age at peak-height velocity

Age at peak-height velocity (APHV) denotes the point of the maximum growth-spurt and has been proposed to be a more objective and non-invasive indicator of age of sexual maturation than the commonly used Tanner stages (Khairullah et al., Reference Khairullah, May, Tilling, Howe, Leonard, Perron, Richer, Veillette, Pausova and Paus2013). In ALSPAC, APHV was derived using a superimposition by translation and rotation mixed effects growth curve analysis based on repeated height measurements through development (Frysz et al., Reference Frysz, Howe, Tobias and Paternoster2018). The resultant measure was used to investigate the influence of pubertal status as a moderator of sex differences in PTSSFootnote 2.

Additional variables

Information on the sex of the child was obtained from birth notifications, and demographic variables (household income, highest maternal educational qualification, child ethnicity, maternal relationship status and maternal smoking) were collected during pregnancy or shortly after delivery via maternal report. In order to examine the possibility of selective attrition, we used data from the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) collected from parents at 8 years, as an extremely well-established index of child emotional and behavioural problems.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata 14 (Stata Corp., 2016). We compared participants included in analyses with those excluded due to missing data using χ2 and t tests as appropriate. Furthermore, we used logistic regression to test for sex differences in exposure to traumatic events. Levels of PTSD symptoms in males v. females were compared using Mann-Whitney-U tests, as they were not normally distributed. We tested for sex differences in overall PTSS and PTSD core symptoms in participants exposed to trauma at each age, using logistic regression, adding APHV as a moderator in a second step by including an interaction term.

Results

Descriptive statistics

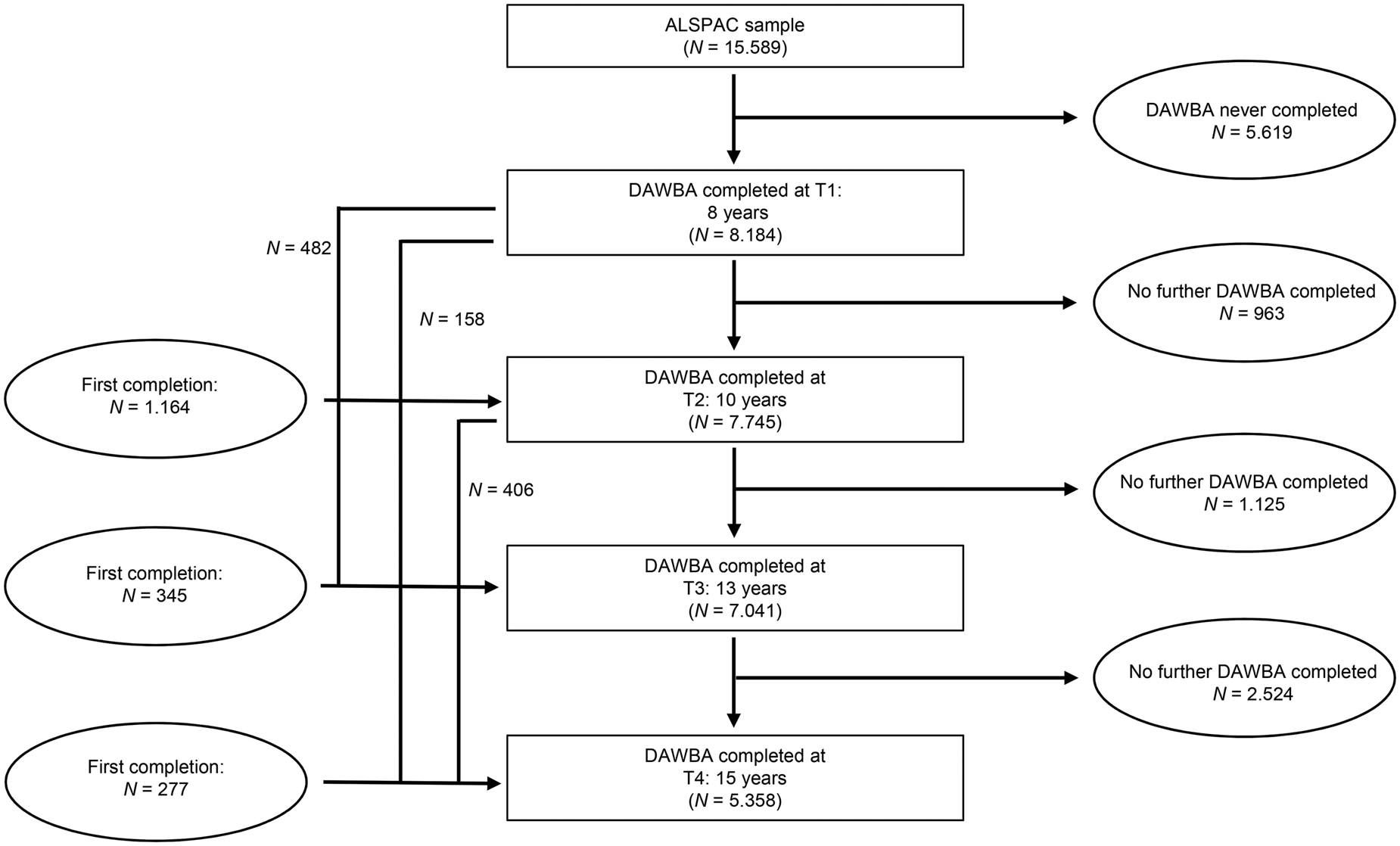

Figure 1 summarises the number of participants and observations available at each age; 9966 participants completed at least one DAWBA assessment across all 4 time-points, 50.7% males (n = 5051) and 49.3% females (n = 4915). DAWBA PTSD assessments at every age (8, 10, 13 and 15 years) were available for a core group of n = 3741 children and adolescents. For an additional n = 1756, all three parent ratings were completed (ages 8, 10 and 13), leading to a full parent-report sample of n = 5497. Further descriptive data can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 1. DAWBA PTSD-assessment availability for the ALSPAC cohort at ages 8, 10, 13 and 15, based on the N = 15.589 children for whom initial assessments were collected.

Table 1. Sample descriptive data (N = 9966) based on assessments during pregnancy/shortly after birth

Attrition

Attrition from the ALPSAC sample has been found to be systematically related to factors such as larger family size, financial difficulties, and the mother being single, a smoker and not having educational qualifications (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Tilling, Galobardes and Lawlor2013). In addition, we found lower SDQ total problem scores as rated by parents at the age of 8 in those who completed at least one more DAWBA assessment after the age of 8 v. those who did not complete any further assessments (M retained = 6.30, M dropout = 7.24, t (5828) = 3.09, p = 0.001). Similarly, those who had been exposed to a potentially traumatic event at 8 years were more likely to have no subsequent DAWBA assessments than those not exposed (14.6% of exposed children dropping out v. 11.4% of non-exposed, χ2 = 9.42, p = 0.002). However, no sex differences in the proportions of trauma exposed dropping out were found at any age (p > 0.21–0.81).

Trauma exposure rates

Child trauma exposure rates by sex are presented in Table 2, based on parent report at 8, 10 and 13 years, and self-report at 15 years. Logistic regressions showed there were no differences in exposure rates between males and females at 8, 10 or 13 years (see Table 2), but at 15 years females were 35% more likely to report trauma exposure than males. The majority of events indexed were rated as ‘severely distressing’ (parent report 8 years: 69.2%, 10 years: 72.1%, 13 years: 70.1%; adolescent self-report 15 years: 78.6%).

Table 2. Trauma exposure rates, according to age and sex

OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Notes. The 15 years-assessment was obtained via self-report, while all other reports are parent-based.

PTSS scores

For the subgroup of children and adolescents who had been exposed to trauma, current symptom scores at each time point are presented in Table 3. Average current symptoms were low at all time-points but spanned a wide range. No sex differences in symptom levels were found at 8 years, Z = −0.47, N = 1031, p = 0.642, or 10 years, Z = −0.10, N = 1231, p = 0.925. However, Mann-Whitney U tests revealed higher symptoms in females than males at 13 years, Z = −2.91, N = 1159, p = 0.004, and 15 years, Z = −3.98, N = 654, p < 0.001. When analyses were rerun excluding symptoms that show strong overlap with depression, the pattern of results remained the same, with females having higher core PTSD symptom scores at 13 years, Z = −4.14, N = 645, p < 0.001, and 15 years, Z = −4.12, N = 654, p < 0.001, but not at 8 years Z = −1.36, N = 1031, p = 0.17 or 10 years Z = −0.1.44, N = 1231, p = 0.15.

Table 3. DAWBA mean symptom scores and current presence of PTSD symptoms by age and sex, based on trauma exposed subgroup at each time point

Notes. The 15 years-assessment was obtained via self-report, while all other reports are parent- based.

Presence/absence of PTSS

Table 3 also presents the proportion of trauma exposed participants who did and did not report PTSS split by sex. For those classed as PTSS present (based on at least one symptom being experienced ‘a lot’) symptom scores were as follows: 8 years Mdn = 6, interquartile range (IQR) = 5–10, 10 years Mdn = 8 (IQR = 5–11); 13 years Mdn = 7 (IQR = 5–10); and 15 years Mdn 12 (IQR = 8–16). Binary logistic regressions were performed, using sex (0 = male, 1 = female) as a predictor for category membership of ‘PTSS present’, (0 = no, 1 = yes). Results showed that sex was not associated with PTSS at 8 years (χ2 = 0.60, p = 0.44; OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.84–1.48) or 10 years (χ2 = 0.042, p = 0.5; OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.84–1.43), but at age 13, females were more likely to report PTSS (χ2 = 9.84, p = 0.002; OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.17–2.02). Similarly, at 15-years females were more likely to self-report PTSS than males (χ2 = 10.64, p = 0.001; OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.31–3.32). Furthermore, when we repeated analyses examining only core PTSS (i.e. removing overlapping depression items), the pattern was almost identical; there were no sex differences at 8 years (χ2 = 1.16, p = 0.28; OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.87–1.61) or 10 years (χ2 = 0.90, p = 0.34; OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.86–1.52), but females were more likely to be symptomatic at 13 years (χ2 = 8.53, p = 0.004; OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.14–2.04) and at 15 years (χ2 = 10.33, p < 0.001; OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.31–3.30).

Moderation by pubertal status

Pubertal status as indicated by APHV was available for a subset of N = 5707 participants of the overall study sample (2685 males and 3018 females). APHV means were M = 13.53, s.d. = 0.86 (range: 10.84–16.56) for males and M = 11.08, s.d. = 0.82 (range: 9.01–14.58) for females. Moderation analyses were performed for ages 13 and 15 only, as these were the only ages at which sex differences in PTSS were found. Binary logistic regression found no evidence of an interaction between sex and APHV at 13 years (B interaction = 0.05, s.e. = 0.21, p = 0.804) in predicting presence/absence of PTSS. However, there was evidence of an interaction between sex and APHV at 15 years (N = 588, χ2 = 13.68, p = 0.003; B interaction = 0.58, s.e. = 0.29, p = 0.046). Follow-up regression analyses revealed APHV was negatively related to whether or not PTSS were present in males (B = −0.44, s.e. = 0.24, 95% CI −0.91 to 0.03), while the association was small and positive in females (B = 0.14, s.e. = 0.26, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.45), indicating that having reached the point of maximum growth spurt later was associated with lesser symptoms in males. However, as confidence intervals each crossed zero, these effects should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

In a large longitudinal birth cohort, we found reliable evidence that sex differences in PTSS emerge during adolescence. Specifically, males and females showed similar risk of PTSS following trauma at 8- and 10-year assessments. However, from the age of 13 years females more frequently presented with PTSS after trauma exposure and showed higher average symptom levels. Sex differences were not accounted for by overlap between PTSS and depressive symptoms. In addition, we found little evidence that pubertal status accounted for heightened vulnerability to PTSS in adolescent females v. males.

Similar to previous cross-sectional analyses (Trickey et al., Reference Trickey, Siddaway, Meiser-Stedman, Serpell and Field2012), we found that from 13 years onwards, trauma exposed females were more likely to be symptomatic and exhibited higher average PTSS levels when compared to their male counterparts. By 15 years of age, females compared to males in the current study were approximately twice as likely to develop PTSS following trauma exposure, which is comparable to the sex difference reported in adult samples. Sex differences in PTSS did not appear to be secondary to overlap between PTSS and depressive symptoms, with the emergence of sex differences during adolescence in the latter being well-established (Wade et al., Reference Wade, Cairney and Pevalin2002). That we were able to study the same sample repeatedly from childhood to adolescence, to examine levels of PTSS only in the subgroup exposed to trauma, and that we could rule out sex differences in selective attrition related to PTSSS, are strengths that make the current findings particularly reliable.

The source of sex differences in PTSS/PTSD, and particularly the reason for their emergence in adolescence, remains to be explained. We focused on comparing symptoms within the subgroup of the ALSPAC sample that reported exposure to trauma, and we only found evidence of higher exposure rates in females at 15 years. The fact that sex differences were apparent within our trauma exposed subgroup means that differences in exposure rates are not an obvious explanatory factor. However, we cannot rule out unmeasured underlying sex differences in quality or extent of exposure. It has been proposed that females may be particularly vulnerable to developing PTSS following interpersonal trauma, and may experience different types of trauma to males (e.g. higher rates of sexual abuse in females), or be exposed to higher accumulated trauma over their lifetime (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, Peterson and Lucia1999; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Carey, Mohr, Stein and Seedat2004), although in the adult field such effects seem to offer limited explanation of sex differences. In the current study it was not possible to meaningfully categorise the type or severity of the young person's trauma exposure. Moreover, the fact that overall rates of reported exposure dropped between 13 years (parent report) and 15 years (adolescent report) was unexpected and underscores the need for more comprehensive measurement of traumatic events. We strongly recommend that future studies include standard trauma checklists to examine possible sex differences in exposure comprehensively.

We examined pubertal status as a key, sex-related biological development, and found little evidence that pubertal development as assessed via APHV contributes to sex differences in PTSS at 13 years. At 15 years, a later pubertal onset appears to be protective against PTSS development in males. The equivalent effect in females was extremely small and positive in direction. Overall, these findings do not offer a clear explanation of the relatively increased risk of PTSS in females during adolescence. It is important to note that APHV may indicate an earlier stage of puberty for females v. males (Granados et al., Reference Granados, Gebremariam and Lee2015); in females most growth and development of sex characteristics occurs in early puberty, before menarche, whereas in boys substantial hormonal changes occur before physical signs are present. As such, APHV is likely to co-occur with Tanner stages 1–3 in girls – and to be more closely coupled with endocrine changes – v. stages Tanner stages 4–5 in boys. The complexity of assessing of puberty, as a multifaceted and gender specific process, means that the current findings must be interpreted cautiously. Nonetheless, we found no evidence to support the possibility that the onset of puberty particularly increases vulnerability to PTSS development in females. Measurement of hormones, such as estrogen and orexin, which have been implicated in symptom development, could yield different conclusions (Grafe and Bhatnagar, Reference Grafe and Bhatnagar2018).

Other factors may also explain sex differences in PTSS. Adolescent females may exhibit more problematic psychological responses to trauma than males. For example, adolescent girls may be particularly likely to cope with stress through rumination, which may prolong difficulties (Hampel and Petermann, Reference Hampel and Petermann2005). More broadly, females may possess different biological vulnerabilities in terms of HPA axis, neural circuits and epigenetic factors (Olff et al., Reference Olff, Langeland, Draijer and Gersons2007; Garza and Jovanovic, Reference Garza and Jovanovic2017; Ramikie and Ressler, Reference Ramikie and Ressler2018). Socio-demographic variables, such as differences in the emotional support given to adolescent females v. males, may also all potentially drive sex differences (Green et al., Reference Green, Korol, Grace, Vary, Leonard, Gleser and Smitson-Cohen1991; Bernard-Bonnin et al., Reference Bernard-Bonnin, Hébert, Daignault and Allard-Dansereau2008). Nonetheless, at present sex differences in PTSS remain largely unexplained. The current study highlights adolescence as a key period during which sex differences emerge, and a potentially useful focus for future study of contributing factors.

The current study has several limitations. First, the ALSPAC sample is slightly more affluent than the UK population average, and dropout was higher amongst families experiencing more challenges, including those children who had previously been exposed to a traumatic event, meaning that findings may not generalise to higher risk groups. Second, the DAWBA was administered as a questionnaire, and without a checklist of traumatic events being provided, potentially leading to certain traumas meeting DSM criterion A not being reported, which would have resulted in no further exploration of PTSS. Similarly, there is a risk that events may have been reported that would not typically be classified as traumatic; previous research has found that a proportion of individuals report events that do not meet DSM 5 Criterion A in self-report PTSD measures (Norris and Riad, Reference Norris, Riad, Wilson and Keane1997). That said, quality checks conducted by the research teams indicated that most of the incidents reported can be considered potentially traumatic according to DSM criterion A. Third, interviews relied on parent informants for the first three assessment time points but on the adolescent's own report for the final time point. At age 15 (self-report) there appeared to be somewhat lower rates of both exposure to trauma and PTSS compared to 13 years, but this may be due to the change in informant across these time points. Of note, sex differences in self-reported PTSS at 13 (carer report) and at 15 years (self-report) were consistent, and therefore the emergence of sex differences in adolescence is not attributable to change in informant. Fourth, the APHV variable was only available for a subset of participants for whom a sufficient number of height measures had been collected. However, comprising over 3000 children and adolescents, our sample was still large enough to yield reliable results.

In sum, the current study used data from a large UK cohort to determine rates of trauma-exposure and PTSD symptom development, stratified by age and sex. We found that sex differences in PTSD appear to emerge between the ages of 10 and 13 years. However, the onset of puberty was not found to be a likely explanatory factor for increased female vulnerability in adolescence. Further investigation of the potential drivers of the emergence sex differences in PTSS is warranted. Characterizing such patterns may help to better understand the developmental origin of the sex gap in PTSD prevalence, and to derive adequate preventive measures and interventions.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

Financial support

This work was funded by GW4 grant GW4-AF9-006 to SH. The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref: 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors and they will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). AF is supported by a personal fellowship from the UK Medical Research Council (MR/M009351/1) and works in work at the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol which receives infrastructure funding from the UK MRC (MC/UU/12013/5). RH is supported by an ESRC Future Research Leader grant (ES/N01782X/1) and a University of Bath Prize Research Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

None.