Many efforts in the clinical field of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are being made. However, mental health is also at stake during this outbreak. Psychological distress is already being detected among the healthcare professionals in Asia (Casas, Repullo, & Lorenzo, Reference Casas, Repullo and Lorenzo2002; Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li, & Yang, Reference Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li and Yang2020; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Liao, Huang, Jiang, Zhang, Wang and Zhao2020). Information on the psychological impact of healthcare workers is still limited in European countries. Knowledge of this impact is crucial to establish a Mental Health Crisis Response (Pfefferbaum & North Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020). This study describes the psychological stress experimented by the healthcare workers involved in the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain.

This national, internet-based, cross-sectional survey was performed by the Research Institute of the University General Hospital of Valencia, which was the coordinating center for the Psychological Impact of Coronavirus (PSIMCOV) network. For the stress and psychological impact evaluation, four modified versions of validated tests (Appendix 1), were considered to match a context within the extreme shortage of time; (A) Healthcare Stressful Test for identifying stressing factors at work (Cano, Rodríguez, & García, Reference Cano, Rodríguez and García2007; Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, Reference Carver, Scheier and Weintraub1989), (B) Coping Strategies Inventory for assessing problem solving, self-criticism, emotional expression, willing thoughts, social support, problem avoidance and social support spheres (Aranaz, Mira & Font-Roja Questionnaire, Reference Aranaz and Mira1988; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, Reference Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, Palfai and Pennebaker1995; Tobin, Holroyd, Reynolds, & Kigal, Reference Tobin, Holroyd, Reynolds and Kigal1989), (C) Font-Roja Questionnaire for assessing satisfaction, pressure, relationships, relaxation, adequacy, control and task variety at work (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, Reference Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera2006) and (D) Trait Meta-Mood Scale for assessing interpersonal aspects of emotional intelligence (Haynes & Lench, Reference Haynes and Lench2003; Johnston & Murray, Reference Johnston and Murray2003). Every assessed area was represented by at least one question. We defined the Psychological Stress and Adaptation at work Score (PSAS) as a combined measure of the scores obtained in each of the four tests described.

Data were analyzed using the statistical software R (Core Team, 2013). The p values in the tables were calculated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean of PSAS. Variables region and psychotherapy were studied with ANOVA analysis and a Tukey's test for multiple comparisons of means. For the variable Children <12 years old, elderly or handicapped at home, we carried out a t test.

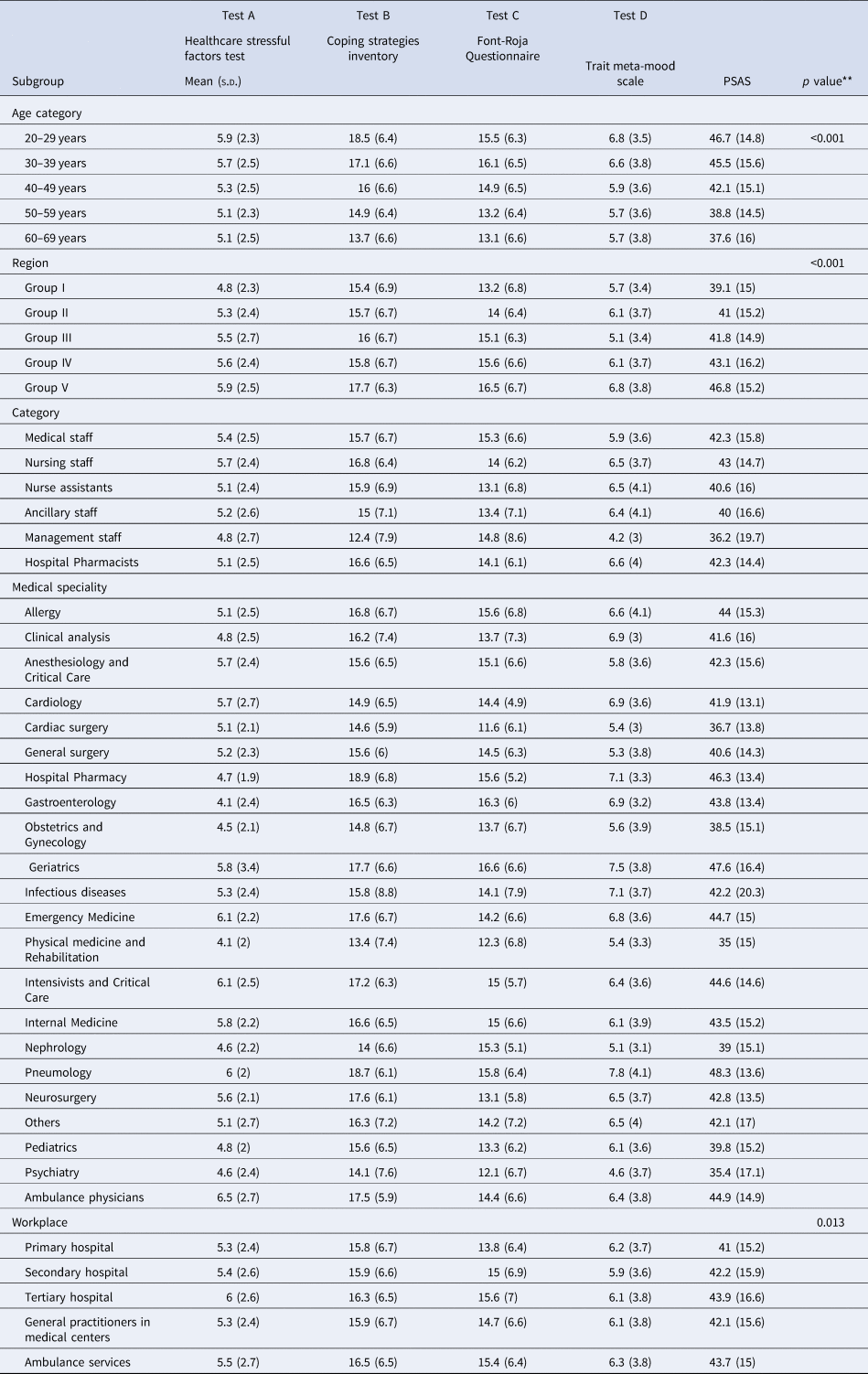

A total of 3109 surveys were analyzed from 9 to 19 April 2020, the most epidemiologically stressful stage of the emergency. Table 1 shows demographics and the main characteristics of the participants of the study. Table 2 shows the global psychological impact results measured by PSAS. Age and the stress perceived, are inversely correlated (p < 0.0001) as seen in a linear regression model reflected in Fig. 1. For analytical purposes, the Spanish geography was divided into five areas based on cumulative incidences defined by the National Health Authority. Healthcare workers in the areas with a higher number of cases (Group V), showed a higher degree of stress globally and in each separated test (p < 0.0001) with a mean (s.d.), PSAS 46.8 (15.2).

Fig. 1. Linear regression between the variables Age and PSAS.

Table 1. Characteristics of the respondents

*Group I: 19.7–33 cases per 100 000 people.

Group II: 34–70.8 cases per 100 000 people.

Group III: 70.9–117.9 cases per 100 000 people.

Group IV: 118–245.8 cases per 100 000 people.

Group V: 245.9–351.3 cases per 100 000 people.

Table 2. Psychological impact on the healthcare workers

*Group I: 19.7–33 cases per 100 000 people.

Group II: 34–70.8 cases per 100.000 people.

Group III: 70.9–117.9 cases per 100 000 people.

Group IV: 118–245.8 cases per 100 000 people.

Group V: 245.9–351.3 cases per 100 000 people.

** p values correspond to one-way ANOVA comparing the mean of PSAS by each of the categorical variables.

Tertiary hospital workers showed a higher level of stress, PSAS 43.9 (16.6) along with ambulance services, PSAS 43.7 (15) when compared to other groups (p < 0.0001). Seniority was a protective factor, PSAS 39.1 (15.2) (p < 0.0001). Other elements analyzed that might interfere in the psychological impact experimented are shown in Table 3. Respondents who felt they needed psychological support but did not have the time to receive it, showed a higher degree of stress, PSAS 52.5 (13.6) compared to those who did not need it, PSAS 39.7 (14.9) (p < 0.0001). Asymptomatic workers were less stressed with a PSAS 41.3 (15.4), than the symptomatic group, in isolation, or those who were positive in a COVID-19 test or were hospitalized (p < 0.001). Familiar exposure is also a determinant factor (p < 0.0001). Figure 2 shows a sub-analysis among different healthcare careers and work environment.

Fig. 2. PSAS career mean by work environment.

Table 3. Precipitating factors and PSAS

*p values correspond to one-way ANOVA comparing the mean of PSAS by each of the categorical variables.

The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in healthcare workers in Spain, has been evaluated. The stress level perceived is predominant in workers that have been in contact directly with COVID-19 patients, like Respiratory Medicine, and in those with family exposure. In the Emergency Medicine (Portero de la Cruz, Cebrino, Herruzo, & Vaquero-Abellán, Reference Portero de la Cruz, Cebrino, Herruzo and Vaquero-Abellán2020), workers have also suffered a high impact. This may be indicative that in this environment, COVID-19 exposure is uncertain. The protective effect of seniority may be due to the fact that, expertise and confidence, helps minimizing the stress caused by unforeseen situations. The number of cases in a geographical area was also a conditioning element for the stress. The higher the incidence the disease is, the more stressed the healthcare workers feel (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li and Yang2020).

This study has several limitations, the critical nature of the emergency, did not allow to obtain a previous assessment of stress levels or the use of an extended version of the tests. More than 66% of the respondents were working on the second least-affected area, so the reported stress impact could be underestimated.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest psychological impact study on healthcare workers during a major pandemic crisis, to date(Kang et al., Reference Kang, Ma, Chen, Yang, Wang, Li and Liu2020). Psychological support has demonstrated to minimize the negative impact on healthcare workers. Novel therapy approaches such as on-line support, mindfulness, relaxation therapies, etc. may have a promising role (Xiao, Reference Xiao2020; Yang, Yin, Duolao, Rahman, & Xiaomei, Reference Yang, Yin, Duolao, Rahman and Xiaomei2020) when the lack of time is a precipitating agent. A second survey will be carry out to assess stress levels among healthcare workers after the crisis finally ends.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001671.

Conflicts of interest

None.

*PSIMCOV NETWORK

Ricardo Salcedo, MD, Medical Director, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Pilar Albors, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Pablo Alcocer, MD, Hospital Nisa 9 de Octubre, Valencia (Spain); Mónica Álvarez, Hospital Universitario de Burgos, Burgos; Mara Andrés, MD, Hospital La Fe, Valencia (Spain); Fernando Antón, Anaford Abogados, Valencia (Spain); Francisco de Asís Aparisi, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Daniel Arnal, MD, Hospital de Alcorcón, Madrid (Spain); Carmen Baixauli, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Maria Teresa Ballester, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Laura Barragán, MD, Centro de salud el Vedat de Torrente, Valencia (Spain); Vibiana Blanco, MD, Centro de salud Trafalgar, Valencia (Spain); Paula Bovaira, Hospital Intermutual, Valencia (Spain); Maria Brugada, MD, Hospital La Fe, Valencia (Spain); Nerea Bueno, MD, SAMU, Valencia (Spain); Antonio Cano, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Eva Carbajo, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Beatriz Carrasco, MD, Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca (Spain); Marta Castell, MD, Hospital La Fe, Valencia (Spain); Isabel Catalá, diseño gráfico, Valencia (Spain); Pablo Catalán, MD; Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia (Spain); Lucía Cervera, Southport District General Hospital, Liverpool (UK); Irina Cobo, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Dolores de las Marinas, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Gema del Castillo, MD, Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia (Spain); Alejandro Duca, MD, Hospital de Manises, Valencia (Spain); Juana María Elía JM, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Cristina Esteve, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Silvia Ferri, MD, Hospital de Torrejón, Madrid (Spain); Juana Forner, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Óscar Gil, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Marta Gómez-Escolar, MD, Emergencias Sanitarias Castilla y León, Valladolid (Spain); Rosa Hernández, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Vega Iranzo, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Raúl Incertis, MD, Hopital de Manises, Valencia (Spain); Ana Izquierdo, MD, Hopital de Manises, Valencia (Spain); María Teresa Jareño, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Eva Jordá, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Nela Klein-González, MD, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona (Spain); Pau Klein-González, digital marketing, Valencia (Spain); Amparo Lluch, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); María Dolores López, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Sara López, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Eva Mateo, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Amanda Miñana, MD, Hospital de Gandía, Valencia (Spain); Sergio Mont, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Maria Carmen Navarro, Researcher, Fundación Hospital General de Valencia (Spain); Pilar Ortega, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Alessandro Pirola, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Pablo Renovell, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Esther Romero, MD, Hospital Clínico de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Javier Ripollés, Hospital Infanta Leonor, Madrid (Spain); Susana Royo, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Juan Ramón Ruiz, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Moisés Sánchez, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Nerea Sanchís, MD, Hospital General de Valencia (Spain); Francisco Sanz, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Silvana Serrano, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Jose Luis Soriano, MD, NHS Bedfordshire Hospitals, Bedford (UK); Ana Tirado, MD, Hospital Infanta Leonor, Madrid (Spain); Francisco Verdú, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain); Enrique Zapater, MD, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia (Spain). In collaboration with SEDAR (Sociedad Española de Anestesia, Reanimación y Terapeútica del dolor), SEPYPNA (Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría y Psicoterapia del Niño y el Adolescente), SENSAR, REDGERM y el COMV (Colegio Oficial de Médicos de Valencia).