Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death across the life-course, with 700 000 deaths each year around the world (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Kleiman, Kellerman, Pollak, Cha, Esposito and Boatman2020; Naghavi, Reference Naghavi2019; Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016; World Health Organization, 2021). Every suicide is a tragedy affecting not only the person who died by suicide, but also networks of people who knew the deceased and who might be in need of support (Cerel et al., Reference Cerel, Brown, Maple, Singleton, van de Venne, Moore and Flaherty2019).

While suicide is a multifactorial phenomenon involving complex interactions between a range of risk and protective factors (Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016), one factor that has attracted considerable public attention recently is peer and bullying victimisation (Moreno, Gower, Brittain, & Vaillancourt, Reference Moreno, Gower, Brittain and Vaillancourt2019). Peer and bullying victimisation are the experience of being the target of the aggressive behaviour by others from the same age group (Finkelhor, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Turner and Hamby2012; Hawker & Boulton, Reference Hawker and Boulton2000). It can include being pushed or hit, being called names, and made fun of, or being excluded from a group. Bullying is a specific form of peer victimisation which is characterised by an imbalance of power between the perpetrator and the victim, as well as repetition of the acts (Olweus, Reference Olweus1993). While children from diverse cultural and geographic backgrounds are exposed to peer and bullying victimisation (World Health Organisation, Reference Currie, Zanotti, Morgan, Currie, Roberts, Samdal, Smith and Barnekow2012), not all children are equally likely to be exposed to such experiences. Vulnerable children such as those with lower IQ or disruptive behaviours (Oncioiu et al., Reference Oncioiu, Orri, Boivin, Geoffroy, Arseneault, Brendgen and Côté2020), those raised in an abusive home (Lereya, Samara, & Wolke, Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013) and/or who carry a range of genetic vulnerabilities related to these individual characteristics (Schoeler et al., Reference Schoeler, Choi, Dudbridge, Baldwin, Duncan, Cecil and Pingault2019) are more likely to become the victims of their peers.

Prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses and recent observational and quasi-experimental studies found that exposure to bullying victimisation in childhood predicted suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence and early adulthood (Castellví et al., Reference Castellví, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco and Alonso2017; Geoffroy et al., Reference Geoffroy, Boivin, Arseneault, Renaud, Perret, Turecki and Côté2018a, Reference Geoffroy, Boivin, Arseneault, Turecki, Vitaro, Brendgen and Côté2016; Herba et al., Reference Herba, Ferdinand, Stijnen, Veenstra, Oldehinkel, Ormel and Verhulst2008; Holt et al., Reference Holt, Vivolo-Kantor, Polanin, Holland, DeGue, Matjasko and Reid2015; John et al., Reference John, Glendenning, Marchant, Montgomery, Stewart, Wood and Hawton2018; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; O'Reilly et al., Reference O'Reilly, Pettersson, Quinn, Klonsky, Baldwin, Lundström and D'Onofrio2021; Schoeler, Duncan, Cecil, Ploubidis, & Pingault, Reference Schoeler, Duncan, Cecil, Ploubidis and Pingault2018). A previous study from the 1958 British birth cohort reported that individuals who were frequently bullied had higher rates of suicidal ideation in their forties (individuals who reported that life is not worth living or who thought about suicide) than those who had not been bullied (Takizawa, Maughan, & Arseneault, Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014), suggesting that bullying victimisation could act as an early adverse experience placing an individual at risk of later suicide death. Findings from the Finnish 1981 birth cohort study (Klomek et al., Reference Klomek, Sourander, Niemelä, Kumpulainen, Piha, Tamminen and Gould2009), indicated that being the victim of bullying at 8 years was associated with suicide attempts that required hospital admission (n = 42) and suicide mortality (n = 15, 2 females) after statistically controlling for conduct and depression symptoms at 8 years [odds ratio (OR) 6.3 (1.5–25.9) in females and 3.8 (0.99–14.3) in males]. However, as suicide attempts and deaths were combined, the specific association with suicide deaths remained unknown. While studies so far suggest that childhood bullying victimisation may predispose an individual to suicide death, possibly via an association with ideation and attempt, no studies have yet examined the prospective association of childhood bullying victimisation with suicide mortality.

Although suicide ideation, suicide attempts and suicide mortality share a range of common risk factors, specific risk factors have also been identified (Klonsky, Saffer, & Bryan, Reference Klonsky, Saffer and Bryan2018; Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O'Connor, Tilling and Gunnell2019). For example, early adversity, including peer bullying victimisation and abusive home, was not associated with the transition to suicide attempts among individuals who previously experienced suicidal ideation (Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O'Connor, Tilling and Gunnell2019). Insights into the mechanisms leading to suicide may be gained by establishing associations of childhood bullying victimisation with suicide mortality in adulthood.

Using the information on bullying victimisation in childhood and suicide mortality in adulthood collected by the 1958 British birth cohort, we investigated whether being a victim of bullying in childhood was associated with suicide mortality in adulthood. Pre-existing vulnerabilities linked to later suicide mortality such as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) within the family and emotional and behavioural problems are risk factors for exposure to bullying (Arseneault, Reference Arseneault2018; Oncioiu et al., Reference Oncioiu, Orri, Boivin, Geoffroy, Arseneault, Brendgen and Côté2020) and they may either confound the unique association between childhood bullying victimisation and suicide mortality or exacerbate suicidal risk prior to or following exposure to bullying victimisation. Our analyses tested (1) the associations between childhood bullying victimisation and suicide death up to mid-life; (2) whether the associations persisted after accounting for sex and a range of childhood confounders including adverse intra-familial experiences and emotional and behavioural problems; and (3) whether suicide risk associated with bullying victimisation was exacerbated by ACEs and childhood emotional and behavioural problems (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, Taillieu, Salmon, Davila, Stewart-Tufescu, Fortier and MacMillan2020; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Moffitt, Houts, Belsky, Arseneault and Caspi2012; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Yu, Zhang, Bao, Jiang, Chen and Zhen2016).

Methods

Participants

The 1958 British birth cohort, also known as the National Child Development Study, is an ongoing longitudinal national birth cohort of 17 638 individuals born in 1 week of March 1958 in England, Scotland, and Wales and representing 98% of all births in Britain in that week. Details about the cohort, including study design and response rates can be found elsewhere (Power & Elliott, Reference Power and Elliott2006).

Of the 17 638 participants in the birth survey of 1958, we excluded 1168 participants who had emigrated permanently from Britain (up to 2009, as information was not available thereafter) because the National Health Service Central Register is not notified of deaths of emigrants. We further excluded 1524 participants who had died from causes other than suicide by 2012 (most deaths had occurred within the first year of life), leaving 14 946 participants for the analyses on suicide deaths.

Ethical approval was given by the South-East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Childhood bullying victimisation

When participants were 7 and 11 years, mothers were asked about the frequency their child had been bullied by other children: ‘never’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘frequently’. We created a continuous scale by summing participants' scores across the two time points to reflect the frequency of bullying victimisation at both ages. We transformed the scale into Z-scores to ease interpretation (ranging from −0.72 to 3.49 s.d.). While the continuous bullying victimisation frequency score was used as exposure in our main analyses, we also used a categorical variable for consistency across studies on bullying victimisation in this cohort (Brimblecombe et al., Reference Brimblecombe, Evans-Lacko, Knapp, King, Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2018; Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Takizawa, Brimblecombe, King, Knapp, Maughan and Arseneault2017; Takizawa, Danese, Maughan, & Arseneault, Reference Takizawa, Danese, Maughan and Arseneault2015; Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014). Accordingly, we used a three-level childhood bullying victimisation indicator based on responses at both time points: 0 = not been bullied (never at both 7 and 11 years); 1 = occasionally (sometimes at either age); and 2 = frequently bullied (frequently at either age or sometimes at both ages).

Suicide mortality

Participants were linked with death records via the National Health Service Central Register (NHSCR); until 31 August 2012 (end of mortality follow-up year). Similarly to our prior publications on suicidality with this cohort (Geoffroy, Gunnell, & Power, Reference Geoffroy, Gunnell and Power2014; Richard-Devantoy et al., Reference Richard-Devantoy, Orri, Bertrand, Greenway, Turecki, Gunnell and Geoffroy2021), suicides were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes E950–59 (suicide) and E980–89 (undetermined intent) or tenth revision (ICD-10) codes X60–84 (suicide) and Y10–34 (undetermined intent). Suicide and death of undetermined intent were combined (Gunnell et al., Reference Gunnell, Bennewith, Simkin, Cooper, Klineberg, Rodway and Kapur2013). We excluded pending verdicts (ICD-9 code 988.88; ICD-10 code Y33.9). Age at death by suicide was extracted from death certificates and ranged from 18 to 52 years.

Potential confounders

A range of childhood individual and family characteristics were selected based on the literature which includes prior studies with the cohort for their associations with bullying victimisation and suicide mortality (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Takizawa, Brimblecombe, King, Knapp, Maughan and Arseneault2017; Geoffroy, Gunnell, Clark, & Power, Reference Geoffroy, Gunnell, Clark and Power2018b; Geoffroy et al., Reference Geoffroy, Gunnell and Power2014; Richard-Devantoy et al., Reference Richard-Devantoy, Orri, Bertrand, Greenway, Turecki, Gunnell and Geoffroy2021; Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Danese, Maughan and Arseneault2015, Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014).

Individual factors

Childhood emotional and behavioural problems (e.g. miserable, resentful/aggressive) were reported at 7 years by the teachers via the 146-item Bristol Social Adjustment Guide (BSAG) (Stott, Reference Stott1969). Childhood cognitive abilities were assessed via tests of reading (word recognition Southgate test) (Southgate, Reference Southgate1962) and arithmetic, consisting of 10 problems of graded difficulty administered to participants at age 7 years. The two tests were standardised for month and year of assessment and averaged to obtain a summary score.

Family factors

Childhood socioeconomic disadvantage was identified from information on father's social class at birth [grouped as class I or II (professional/managerial), IIINM (skilled non-manual), IIIM (skilled manual) and IV and V (semi-unskilled manual, including single households)], household amenities (bathroom, indoor lavatory, hot water) and household crowding at 7 years. Maternal age at birth was obtained from medical records. ACEs within the family by age 7 years were extracted following a procedure described in prior studies with this cohort (Barboza Solís et al., Reference Barboza Solís, Kelly-Irving, Fantin, Darnaudéry, Torrisani, Lang and Delpierre2015) and identified as a set of stressful familial psychosocial conditions. After the age-7 interview with parents in the participant's home, health visitors recorded information on whether (1) the child has ever been in public/voluntary care services or foster care; the child lived in a household where a family member (2) is in contact with probation service; (3) has mental illness/has contact with mental health service; (4) has alcohol abuse problem; (5) the child has been separated from their father or mother due to death or divorce, or separation. The child's schoolteacher at 7 years reported (6) whether the child appears undernourished or dirty. Exposure to ACEs was identified by an affirmative response to any of the six categories.

Statistical analyses

We examined bivariate associations between each individual and familial characteristic and suicide mortality and childhood bullying. Then, we tested whether the frequency of childhood bullying victimisation (continuous score) was associated with suicide mortality using logistic regressions. We estimated four models (1) unadjusted, (2) sex-adjusted, (3) additionally adjusted for individual characteristics, including childhood emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive skills; and (4) additionally adjusted for familial characteristics including family socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal age at birth and ACEs. We also tested whether associations of bullying victimisation differed by childhood emotional and behavioural problems and by the total number of ACEs. To do so, we estimated two separate models where bullying and (1) emotional and behavioural problems and (2) ACEs, as well as the two-ways interactions between those variables (bullying × emotional and behavioural problems; bullying × ACEs) were used as predictors of suicide mortality. We tested whether bullying victimisation was associated with age at death by suicide. We used linear regressions with age at death by suicide as the outcome and bullying victimisation as the exposure. Finally, we re-estimated our models using bullying categories as the exposure variable (none, occasionally and frequently).

Missing data on bullying victimisation ranged from 13.4% at 7 years to 18.3% at 11 years (e.g. 6.1% of children were missing at both times including one suicide) while for confounders the range was from 0% (sex) to 12.1% (cognitive ability). To minimise data loss, missing data on both childhood bullying victimisation and confounding variables were imputed using multiple imputation chained equations (Azur, Stuart, Frangakis, & Leaf, Reference Azur, Stuart, Frangakis and Leaf2011) with all variables in the models, together with participants' mental health at 16 years, which has been shown to be a key predictor of missingness. Regression analyses were run across 100 imputed datasets. Imputed results were broadly similar to those using observed values (online Supplementary Table S1); the former is presented. Statistics were conducted in SPSS version 26th.

Sensitivity analysis

To complement our inferential statistical approach, and because the analyses relied on a very low frequency of suicide, we applied a Bayesian statistical approach (Schmalz, Biurrun Manresa, & Zhang, Reference Schmalz, Biurrun Manresa and Zhang2021) to quantify evidence for the alternative (H1) relative to the null (H0) hypotheses using R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2020) with package brms (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017) and bayestestR (Makowski, Ben-Shachar, & Lüdecke, Reference Makowski, Ben-Shachar and Lüdecke2019). A Bayes factor (BF10) is the ratio between the evidence that supports an association of bullying victimisation with suicide (H1) over the evidence supporting no association between bullying victimisation and suicide (H0). BFs greater than 1 usually indicate relative evidence for H1, whereas those smaller than 1 indicate relative evidence for H0. BFs ranging between 1–3 and 3–10 suggest anecdotal and moderate evidence for H1, respectively, whereas a BF greater than 10 represents strong evidence for H1 (Aczel, Palfi, & Szaszi, Reference Aczel, Palfi and Szaszi2017). BFs were calculated using bridge-sampling (Gronau, Singmann, & Wagenmakers, Reference Gronau, Singmann and Wagenmakers2020). All models were evaluated using non-informative priors [log student-t (3, 0, 2.5)], which are the default priors in brms.

Results

Fifty-five participants had died from suicide (0.36%; 48 males and 7 females) by age 52 years; the median age of suicide was 41 years (range 18–52 years) for men and 44 years (range 21–49 years) for women.

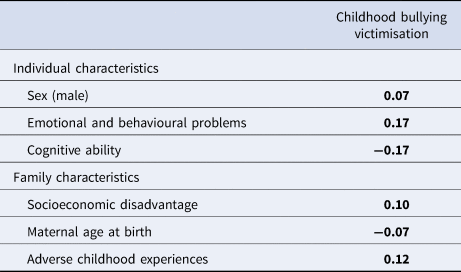

Table 1 shows Pearson correlations for suicide mortality and potential confounders and online Supplementary Table S2 Pearson correlations between potential confounders. Individuals who died by suicide had a pattern of greater levels of individual and familial vulnerabilities than their counterparts. In addition, individual and familial characteristics were correlated with childhood bullying victimisation (Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (mean, s.e. or %, N) for suicide mortality in adulthood by childhood individual and family factors±

± Based on imputed data (n = 14 946 for suicide mortality).

a Based on t tests or χ2.

Table 2. Correlations between childhood individual and family factors and bullying victimisation±

Based on Pearson correlations. Bolded estimates are statistically significant; p < 0.05.

± Based on imputed values, n = 14 946.

Table 3 shows OR and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of childhood bullying victimisation score with suicide mortality. In unadjusted models, the bullying victimisation scale was associated with increased odds of suicide mortality (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.02–1.64). That is, every standard deviation increases in the bullying victimisation scale was associated with a 29% increase in the odds of suicide mortality. The odds attenuated by 7% after controlling for sex (OR 1.23; 95% CI 0.97–1.57) and by 4% further after accounting for individual and familial vulnerabilities (1.18; 95% CI 0.92–1.51). We found no evidence for a moderating effect of childhood emotional and behavioural problems or ACEs (p values for interaction terms were 0.870 and 0.743 respectively). Additional analyses with an age of death by suicide as the outcome indicated that bullying victimisation was not associated with age at death by suicide (unadjusted ß = 0.25, s.e. = 1.15; p = 0.826; fully adjusted (model 4) ß = 0.434, s.e. = 1.23; p = 0.725).

Table 3. OR (95% CI) for the association of childhood bullying victimisation with suicide mortality by mid-adulthood±

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

± Based on imputed values (n = 14 946).

a The model is adjusted for sex and individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability.

b The model is adjusted for sex, individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability and family characteristics including socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal age and adverse childhood experiences.

Further, analyses of bullying victimisation as a categorical exposure showed that frequent bullying victimisation was marginally associated with an increased risk of suicide death, although CIs were wide due to low prevalence of suicide (Table 4). Associations reduced after adjustment for individual and familial vulnerabilities: OR for suicide death from 1.89 (0.99–3.62) to 1.45 (0.74–2.83).

Table 4. OR (95% CI) for the association of frequent and occasional childhood bullying victimisation with suicide mortality by mid-adulthood±

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence intervals.

± Based on imputed values (n = 14 946).

† Prevalence and n are based on observed data.

a The model is adjusted for sex and individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability.

b The model is adjusted for sex, individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability and family characteristics including socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal age and adverse childhood experiences.

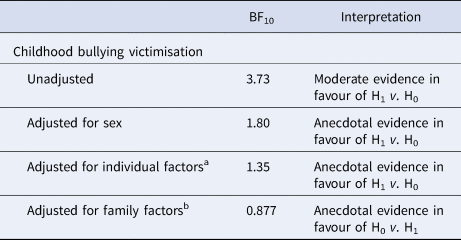

Finally, as shown in Table 5, BFs yield moderate evidence in favour of H1 for the unadjusted model and anecdotal evidence in models adjusting for other childhood individual and familial risk factors pertaining to suicide.

Table 5. Bayes factors calculated for the association between childhood bullying victimisation and suicide mortality by mid-adulthood±

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

± Based on completed case (n = 12 661).

a The model is adjusted for sex and individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability.

b The model is adjusted for sex, individual characteristics including emotional and behavioural problems, and cognitive ability and family characteristics including socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal age and adverse childhood experiences.

Discussion

Bullying and peer victimisation have been associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence (Geoffroy et al., Reference Geoffroy, Boivin, Arseneault, Renaud, Perret, Turecki and Côté2018a, Reference Geoffroy, Boivin, Arseneault, Turecki, Vitaro, Brendgen and Côté2016; Gini & Espelage, Reference Gini and Espelage2014; Holt et al., Reference Holt, Vivolo-Kantor, Polanin, Holland, DeGue, Matjasko and Reid2015; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; Perret et al., Reference Perret, Orri, Boivin, Ouellet-Morin, Denault, Côté and Geoffroy2020) and adulthood (Copeland, Wolke, Angold, & Costello, Reference Copeland, Wolke, Angold and Costello2013; Klomek et al., Reference Klomek, Sourander, Niemelä, Kumpulainen, Piha, Tamminen and Gould2009; Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014). Our study shows, in a 5-decade nationwide prospective cohort, that individuals who have been frequently bullied in childhood had an increased, albeit small, risk of dying by suicide in the adult years, when no other risk factors for suicide were considered.

To our knowledge this is the first prospective study to examine the role of childhood bullying victimisation on later suicide mortality. One prior study by Klomek et al. (Reference Klomek, Sourander, Niemelä, Kumpulainen, Piha, Tamminen and Gould2009) combining information on hospital admission for suicide attempts and mortality by age 25 found an association of frequent bullying victimisation. However, as suicide attempts and deaths were combined with a low number of suicides (n = 15 in total; n = 13 in males) the specific associations with suicide deaths were unknown. The 1958 British birth cohort enabled us to capture a larger group of suicide deaths. A small association of childhood bullying victimisation and suicidal mortality throughout the adult years was detected, which reduced by 11% after confounding factors were controlled for. This pattern of association was consistent across both continuous and categorical measures of bullying victimisation. A prior study in this cohort of the association between frequent bullying (v. not bullied) and suicidality at 45 years reported an adjusted OR of 1.66 (Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014). This estimate is comparable to the OR of 1.45 reported in our study. While both studies allowed for a similar range of confounding factors, the study by Takizawa et al. (Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014) was on suicidality at age 45 years (defined as ‘thought that life is not worth living’ and ‘thought of killing yourself in the past week’) with a higher statistical power than our study of suicide deaths.

Our findings do not support the assumption that pre-existing individual (childhood emotional and behavioural problems) and familial (adversity) vulnerabilities could exacerbate suicidal risk following bullying victimisation, although this finding warrants replication given the low number of suicide deaths (and related lower power to detect such effect). Our findings nevertheless point towards a cumulative effect of bullying with other forms of adversity (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, Taillieu, Salmon, Davila, Stewart-Tufescu, Fortier and MacMillan2020). Indeed, our study suggests that individuals exposed to the highest levels of bullying victimisation were also exposed to other forms of adverse experiences in their family, hence cumulating risk factors for suicide. Further, while prior studies have shown that there is a continuity of victimisation (including bullying victimisation) across ages (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, Reference Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner2007), our measure of bullying victimisation only captures two time points in childhood. Victimisation may have continued into later life (i.e. re-victimisation and poly-victimisation). Altogether, interventions that contribute to break this vicious cycle of violence victimisation may help to reduce the risk for suicide.

In this cohort, most suicides occurred in the early forties and while we did not detect an association between childhood bullying victimisation and age at the time of death, we can not rule out the possibility that bullying victimisation might increase suicide risk factors that are in closer temporal proximity, that is, during adolescence or emerging adulthood. Of note, interpersonal conflicts and relationship difficulties are often cited as key precipitants of suicide death in psychological autopsy studies (Marttunen, Aro, & Lönnqvist, Reference Marttunen, Aro and Lönnqvist1993) and bullying victimisation was reported in about one-quarter of suicides in people younger than 20 years (Rodway et al., Reference Rodway, Tham, Ibrahim, Turnbull, Windfuhr, Shaw and Appleby2016). However, in an observational study based on 94 youth suicides in Canada, bullying had been mentioned in coroners' verdicts for a few suicides only, with more common proximal stressors mentioned being conflict with parents or romantic partners (Sinyor, Schaffer, & Cheung, Reference Sinyor, Schaffer and Cheung2014). Further, recent studies indicate that the new form of bullying victimisation, cyberbullying, is more strongly associated, in the short term, with suicidal ideation and attempts than traditional or face-to-face bullying (Gini & Espelage, Reference Gini and Espelage2014; Perret et al., Reference Perret, Orri, Boivin, Ouellet-Morin, Denault, Côté and Geoffroy2020). Studies with measures of all forms of bullying, including cyberbullying, and records of suicide by early adulthood are needed to further build the evidence base for the association of bullying victimisation and suicide mortality.

Methodological considerations

Our study population is large and nationally representative of British residents born in 1958, and captures for the first time, prospectively collected information on childhood bullying victimisation and suicide mortality over five decades of life. However, our results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, our study may be underpowered to detect an increasing risk of death by suicide, a rare phenomenon, among individuals who were bullied in childhood. For our bullying victimisation score, CI were wide, i.e. such as 1.02 to 1.64 in the unadjusted model, suggesting that the estimated risk ranges between 2% and 64% increase in suicide mortality (or between 8% decrease to 51% increase when adjusting for all potential confounding factors). The estimation of BFs similarly provides moderate evidence for an association of bullying victimisation with suicide mortality, and anecdotal evidence for rejecting the alternative hypothesis after controlling for other childhood risk factors for suicide. Second, while information on a set of key potential confounding factors was available, some factors (e.g. cognitive ability and childhood emotional and behavioural problems) were measured concurrently with bullying victimisation. Because bidirectional associations exist between bullying victimisation and these individual characteristics (Brunstein Klomek et al., Reference Brunstein Klomek, Barzilay, Apter, Carli, Hoven, Sarchiapone and Wasserman2019), we cannot exclude the possibility of inverse causality, and thereby to a risk of over-adjustment in our models. Accordingly, the inclusion of these confounders may have reduced the power to detect an association. between bullying and mortality. Third, our bullying victimisation measure was based on a single question administered to mothers (was your child ever bullied by other children), albeit at two separate ages, and no definition of bullying was provided. As parents may not be aware of all experiences of bullying victimisation (Stockdale, Hangaduambo, Duys, Larson, & Sarvela, Reference Stockdale, Hangaduambo, Duys, Larson and Sarvela2002), their occurrence might have been underreported by mothers, hence leading to misclassification of some children into the ‘not bullied’ category, which could have further reduced power. Despite these limitations in measurement, prior studies based on the 1958 British birth cohort reported consequences of bullying victimisation on a range of outcomes including midlife mental health (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Takizawa, Brimblecombe, King, Knapp, Maughan and Arseneault2017; Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2014), income (Brimblecombe et al., Reference Brimblecombe, Evans-Lacko, Knapp, King, Takizawa, Maughan and Arseneault2018; Takizawa et al., Reference Takizawa, Danese, Maughan and Arseneault2015) and inflammatory markers, supporting the construct validity of the bullying measure. Furthermore, reports of bullying victimisation from both mothers and children have been similarly associated with children's emotional and behavioural problems (Shakoor et al., Reference Shakoor, Jaffee, Andreou, Bowes, Ambler, Caspi and Arseneault2011). Fourth, while the cohort captures all births in a single week of March, it does not include children born in the summer or who are young for their school year, and who may be more often targeted due to their greater developmental immaturity (Whitely et al., Reference Whitely, Raven, Timimi, Jureidini, Phillimore, Leo and Landman2019).

Conclusion

Although firm conclusions can't be drawn based on this study alone, our results suggest that childhood bullying victimisation may carry a small risk for suicide deaths in adulthood. However, larger population-based studies are needed to confirm these results and to clarify whether childhood bullying has a separate role beyond other childhood risk factors for death by suicide decades later. Nevertheless, suicide prevention strategies are often recommended to start in childhood, with bullying included in a constellation of co-occurring vulnerabilities encompassing behavioural and emotional difficulties, as well as adverse experiences within the family.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722000836

Acknowledgements

All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR. The funders had no input into study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors acknowledge the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS), UCL Institute of Education, for the use of 1958-NCDS data and the UK Data Service for making them available. Neither CLS nor the UK Data Service bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of these data. We thank Elise Chartrand, research assistant, for her technical support. MCG holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) and is supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). IOM holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2). LA is the Mental Health Leadership Fellow for the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Conflict of interest

None.