The importance of work in enhancing the mental health and quality of life of people who experience mental health problems has been widely documented (Reference Bennett and AuflangeBennett, 1975; Reference ShepherdShepherd, 1984; Reference Rowland and PerkinsRowland & Perkins, 1988; Reference Nehring, Hill and PooleNehring et al, 1993; Reference WarnerWarner, 1994). As well as an income, employment provides social contacts and social support, status and identity, a means of structuring and occupying time and a sense of personal achievement.

Bennett (Reference Bennett and Auflange1975) has characterised work as the performance of a task within prescribed limits to achieve goals set by others, who judge and reward and thereby link the individual to society. Without work, these links are all too easily lost. The centrality of employment in promoting social inclusion is widely recognised by government initiatives, including the New Deal for Disabled People (Department for Education and Employment, 2001).

For many people who have experienced mental health problems, the main barrier to employment is an unwillingness on the part of employers to consider them because of their psychiatric history (Reference Manning and WhiteManning & White, 1995; Reference Rinaldi and HillRinaldi & Hill, 2000). Others have more disabling ongoing problems that can impede work performance. However, research indicates that, with appropriate ongoing support, a mean of 58% of people with serious ongoing mental health problems can achieve competitive employment (Reference Bond, Drake and MueserBond et al, 1997; Reference Crowther, Marshall and BondCrowther et al, 2001). Although such supported employment models were developed in the USA, they are becoming increasingly available in the UK.

Yet, despite the development of effective models to enable people with mental health problems to gain and sustain employment, and despite the introduction of the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995, it remains the case that employment opportunities for such people remain scarce. The 1998 Labour Force Survey showed that 88% of those with longer-term mental health problems are unemployed (Department for Education and Employment, 1998).

The aim of this paper is to examine trends in the vocational status of people with longer-term mental health problems in the London Borough of Wandsworth (1998 Index of Local Deprivation, 25.05 — rank 30th in the country) during the 1990s, and to compare these with local general employment rates.

Method

Data concerning the vocational status of people with longer-term mental health problems during the 10 years from 1990 to 1999 were collected via an annual census of adults using community mental health and rehabilitation teams in the south-west London Borough of Wandsworth. Basic demographic, psychiatric, service usage, accommodation and vocational information was provided by keyworkers for all clients of the services on 1 April each year who had experienced their first contact with psychiatric services at least 2 years previously. Vocational status was reported in five categories: open employment, sheltered work, voluntary work, education and unemployed. Open employment included ordinary, existing, full-time, part-time or casual work gained in open competition. It did not include jobs created under special employment schemes for people with mental health problems.

General unemployment rates were obtained from Wandsworth Local Authority, based on figures provided by the London Research Centre.

Results

Table 1 shows that there was a mean of about 1015 longer-term service users in contact with local mental health services in the Borough of Wandsworth each year between 1990 and 1999, over half of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Table 1. Characteristics of the population of longer-term service users from the boroughs of Wandsworth and Merton, 1990-1999

| Mean total number | 1015 |

| Mean percentage males | 47.1% |

| Mean age, years (s.d.) | 45.6 (14.1) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder | 55.2% |

| Manic depression | 13.7% |

| Depression | 14.5% |

| Anxiety-based problems | 5.8% |

| Other | 11.8% |

Table 2 shows that general employment rates in Wandsworth fell between 1990 and 1993 from 94.5% to 86.2%. Employment rates among those service users with longer-term mental health problems also decreased from 19.7% to 12.3%. However, between 1993 and 1999 general employment rates rose again from 86.2% to 95.1%, but employment rates among service users with longer-term mental health problems continued to fall from 12.3% to 8.1%.

Table 2. Employment rates in Wandsworth, 1990-1999

| Employment rate among longer term service users | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All diagnoses | |||||

| Year | General employment rate in Wandsworth (%) | All clients (%) | Clients aged <35 years (%) | Clients aged >35 years (%) | Schizophrenia (all clients) (%) |

| 1990 | 94.5 | 19.7 | 24.3 | 17.8 | 12.0 |

| 1991 | 91.1 | 18.1 | 23.5 | 16.1 | 10.1 |

| 1992 | 88.0 | 15.8 | 18.0 | 15.2 | 8.3 |

| 1993 | 86.2 | 12.3 | 20.9 | 14.0 | 7.7 |

| 1994 | 87.2 | 15.6 | 21.6 | 13.0 | 7.4 |

| 1995 | 88.7 | 13.3 | 16.5 | 12.2 | 7.7 |

| 1996 | 89.5 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 9.3 | 5.5 |

| 1997 | 92.3 | 8.7 | 11.2 | 7.7 | 4.9 |

| 1998 | 94.1 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 8.5 | 5.7 |

| 1999 | 95.1 | 8.1 | 10.6 | 7.1 | 4.4 |

The situation was even worse among long-term service users with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Between 1990 and 1993 employment rates among this group fell from 12.0% to 7.7%, and continued to fall between 1993 and 1999 to only 4.4%, despite the increase in general employment rates during this period.

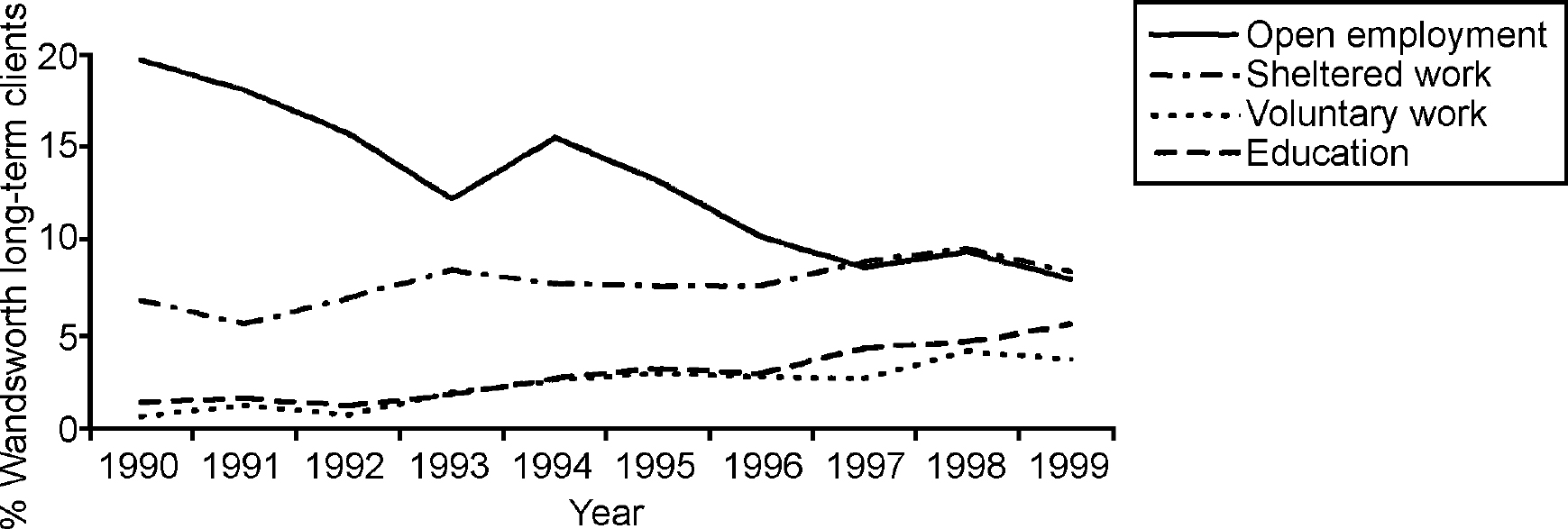

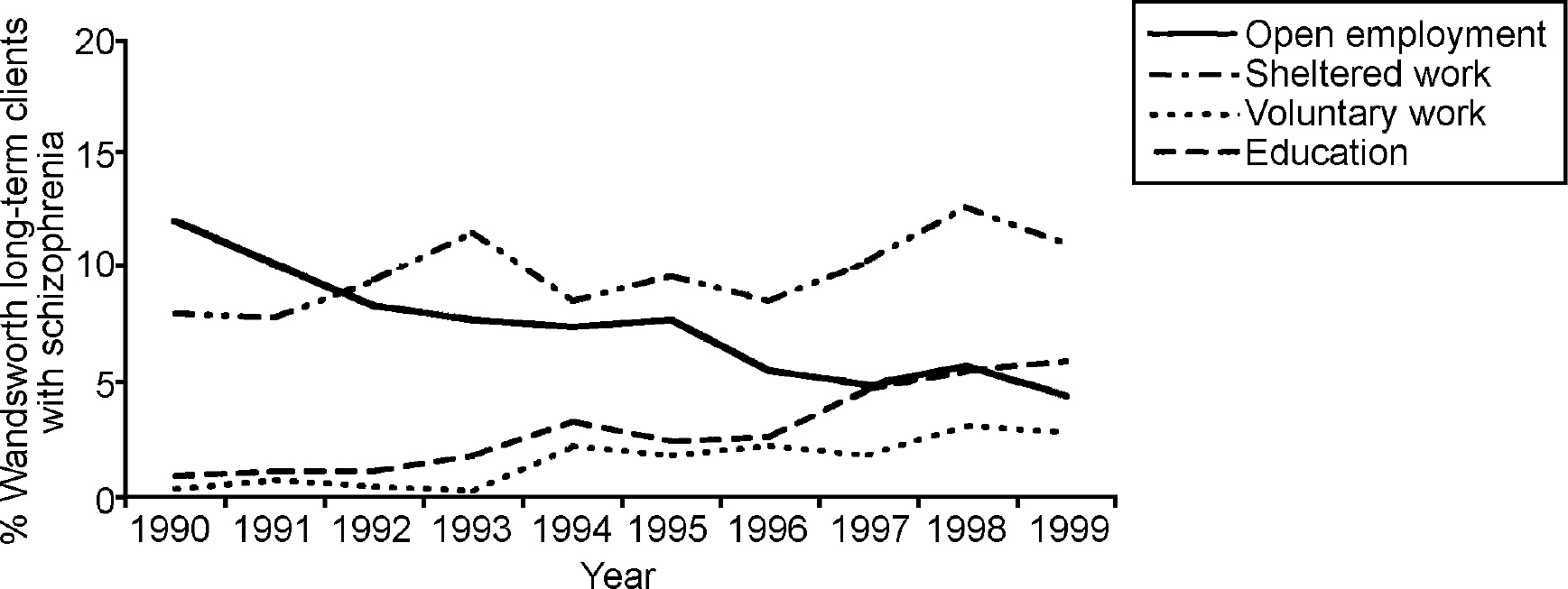

Figs 1 and 2 show that as the proportion of longer-term service users engaged in open employment fell, the proportion engaged in voluntary work rose substantially from 0.6% in 1990 to 3.8% in 1999 (from 0.3% to 2.8% among those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia). Similarly, the proportion engaged in education courses rose from 1.4% in 1990 to 5.7% in 1999 (from 0.9% to 5.9% for those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia). The proportion engaged in sheltered work rose slightly from 6.9% to 8.5% (from 8.0% to 11.0% for those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia).

Fig. 1. Percentages of Borough of Wandsworth long-term clients engaged in work or employment.

Fig. 2. Percentages of Borough of Wandsworth long-term clients with schizophrenia engaged in work or employment.

During the years 1990-1995 there was an expansion of work programmes available to help people with mental health problems in the borough. These included six initiatives providing time-limited work preparation and support to obtain open employment, six services offering training for work, five sheltered work/work experience programmes, the introduction into the volunteer bureau of a worker to assist people with mental health problems in volunteering and links between mental health services and local colleges to facilitate access to education.

Discussion

These data clearly show that, during the 1990s, the proportion of people with longer-term mental health problems in employment decreased substantially in Wandsworth. This decrease did not reflect general employment rates in the manner that might have been expected: employment rates among longer-term mental health service users fell when general employment rates were falling, but continued to decrease when general employment rates rose again. This decrease did not reflect the national data on employment rates for disabled people more generally either, which remained constant at around 40% throughout the 1990s (Reference BurchardtBurchardt, 2000). It is likely that this difference reflects the greater discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems.

The decrease in employment rates among longer-term service users was equally evident for younger (≤35 years) and older (>35 years) people, but throughout the period the employment rates were lower for the older group and slower to fall in the first half of the decade for the younger group, although they declined substantially in the second half. The data also indicate that the decrease in employment rates was greatest among those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, in relation to whom employment discrimination is likely to be most acute (Reference Manning and WhiteManning & White, 1995).

This decrease in employment occurred despite:

-

(a) the widely recognised importance of employment for people with mental health problems;

-

(b) an increasing recognition of the importance of employment in promoting social inclusion;

-

(c) the development of effective models for supporting people with mental health problems in employment (Reference Bond, Drake and MueserBond et al, 1997; Reference Crowther, Marshall and BondCrowther et al, 2001);

-

(d) the introduction of national policies such as the Disability Discrimination Act;

-

(e) policy initiatives such as the New Deal for Disabled People;

-

(f) the development of local initiatives designed to help people with mental health problems get and keep jobs in open employment.

In place of employment, engagement in voluntary work and education have increased. Although these activities may yield benefits in and of themselves, it is often asserted that engagement in such activities can prepare people for entry/re-entry into employment. The continuing downward trend in employment rates indicates that this has not been the case.

There are a number of possible reasons why those with long-term mental health problems might have failed to benefit from the general decrease in unemployment within the economy.

First, it is possible that the type of jobs lost with the economic downturn and those created with the economic upturn were of a different nature. If the jobs lost were primarily entry-level positions requiring few educational qualifications, and those gained were of a more ‘high-tech’ variety, then it is possible that people whose education was disrupted by mental health problems may not be able to avail themselves of the new positions created. Although there are undoubtedly labour shortages at the upper end of the skill range, the Economic Development Department in the borough indicated that there are also labour shortages locally in all positions (London Research Centre, 2001).

Second, during this period there has been increasing pressure to reduce bed usage and ensure that as many people as possible are supported in living outside a hospital setting. This may result in mental health workers devoting most of their time and energy to maintaining people in their accommodation, with relatively little time devoted to other issues such as employment. It should be noted that if there has been a decrease in attention to vocational issues then this is likely to jeopardise community tenure. There is evidence that employment decreases admission rates: those who have work are likely to stay out of hospital for longer periods than those who are out of work (see Reference Nehring, Hill and PooleNehring et al, 1993).

Third, at the same time as there has been a focus on the role of employment in promoting social inclusion, there has been an increasing focus on stress in the workplace and the detrimental impact of some employment on mental health. If it is assumed that work is stressful, and that people who experience serious mental health problems are not able to cope with stress, then there may be a reluctance on the part of clinicians to encourage clients to work, and on the part of clients to undertake an activity that they believe may worsen their difficulties. However, such arguments do not take into account the stressful effects of unemployment and the well-documented detrimental impact of unemployment on mental health.

Fourth, the ‘benefits trap’, which makes it difficult for people with mental health problems to take low paid jobs, especially on a part-time basis, without risking loss of income, is undoubtedly a disincentive to entering employment. The pattern of decreasing employment found did not, apparently, change in response to alterations in benefit regulations during the period considered. Therefore, the benefit system alone is unlikely to explain fully the trends found.

Finally, during the 1990s there has been a major increase in the popular association between violence and mental health: the media are replete with accounts of ‘mad axe-murderers’ wandering the streets. It seems unlikely that employers are immune to such popular representations and they may have become increasingly fearful of employing people who they assume to be dangerous.

Whatever the explanations for the decreasing employment rates found, it is clear that mental health services face a major challenge. Unemployment exacerbates the mental health difficulties of those with serious mental health problems and employment has a central role in promoting inclusion: the continuing decrease in employment among this group is therefore a matter of grave concern. Standard 1 of the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) requires that we combat discrimination against, and promote the social inclusion of, individuals and groups with mental health problems. Standard 5 requires that care plans for people with severe mental illness address arrangements for employment, education/training or other occupation. Standard 7 requires that local health and social care communities minimise suicides among people with mental health problems, and there is evidence of a link between unemployment and increased risk of suicide (Reference Lewis and SloggettLewis & Sloggett, 1998).

If people with serious long-term mental health problems are to have access to employment, there is an increasing body of research evidence from randomised controlled trials (Reference Drake and BeckerDrake & Becker, 1996; Reference Bond, Drake and MueserBond et al, 1997; Reference Crowther, Marshall and BondCrowther et al, 2001) that indicates the need for:

-

(a) vocational rehabilitation to be seen as a central and integral component of the work of mental health teams rather than a separate service — front-line staff must have a vocational orientation and there must be vocational expertise within teams if success is to be achieved;

-

(b) a change in the focus to a supported employment model, with a clear goal of open employment in integrated settings, minimal pre-vocational training, rapid job search, time-unlimited support and work-place interventions, continuing assessment and adjustment of support and vocational needs and attention to user preferences and choices rather than providers' judgements.

The challenge for mental health services is to make employment interventions of demonstrated effectiveness available to all who need them.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.