Formerly Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales

In 1987 Judge Tumim was picked out of relative obscurity to be the Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales. Douglas Hurd was Home Secretary and Stephen was chosen as ‘he was not too right wing or settled in his ways’. Up until then, the Inspectorate of Prisons had deliberately presented a low profile. But things were to change. As a close associate said of Stephen, ‘He took the fight to the enemy’. First, he required that all his reports to the Home Secretary be published. He insisted on his independence and the right to address the media. He increased substantially the announced list of prisons that were to be fully inspected each year and also introduced the practice of shorter, unannounced inspections of other prisons. Together, this eventually produced reports at the rate of one a fortnight. On top of this, he produced reports on specific topics such as the influential ones on the abolition of slopping out and suicide in prisons. All aspects of prison life were reported on, including the state of the prison hospitals and the service they provided. In this context, considerable consideration was given to the problem of dealing with the mentally disordered offender and the unsatisfactory arrangements that so often prevailed through a combination of a lack of National Health Service provision and impoverished or unsatisfactory prison health care centres. These reports formed the background from which his successor, Sir David Ramsbotham, was eventually able to successfully press for the National Health Service to become responsible for medical care in prisons.

Stephen's great contribution was to see the big issues in human terms and communicate them to the country. He articulated the problems so clearly – he spoke for all those, prison staff, inmates, associated trades and professions, who would have the prisons be better places. He raised morale and gave hope that things could be better, that a different view was possible. He made the liberal point of view respectable. His philosophy that the prisons should be used to prepare inmates to be proper citizens through education in its widest sense is outlined in his essay, ‘The Future of Crime and Punishment’.

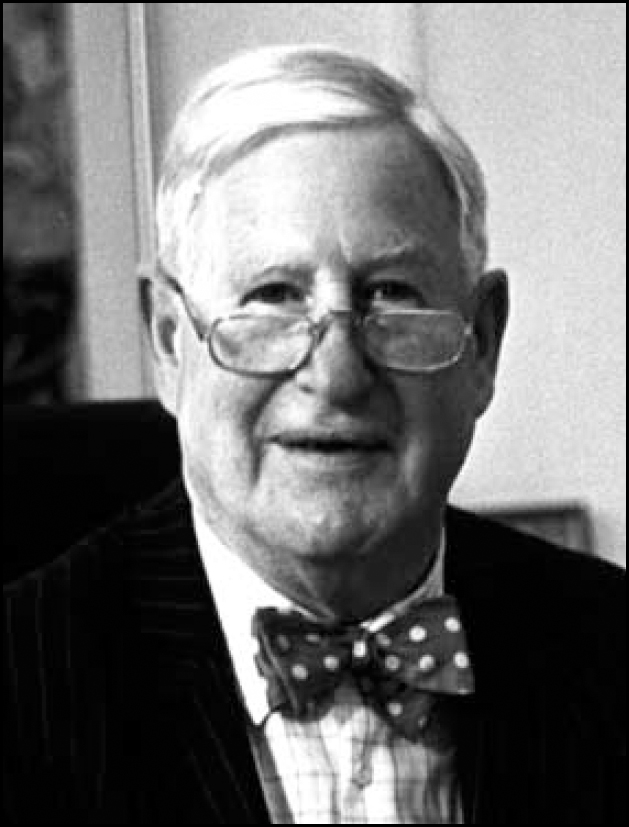

He enjoyed a battle, he liked the lime-light, he enjoyed meeting reporters, being on the television and being a celebrity. He came over well with his genial ‘Garrick Club’ manner, his half-moon spectacles and bow tie, his disarming directness and his obvious humanity. While his main purpose was to present the findings of his inspections to the Home Secretary, he was also outstandingly successful at making the public aware of the prisons and their problems. His reports were direct and hard-hitting. Through his reports, he set the standards necessary to meet the Government's own stated aims. He was feted, received Honorary Degrees, was elected (Honorary) Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 1993 and was Knighted in 1996.

His childhood was spent in Oxford, the son of the Clerk of the Assize of the Oxford Circuit. Schooling was at Saint Edward's, Oxford. He came to love and collect books and wandered around befriending booksellers in Oxford during his adolescence. He was a scholar of Worcester College and finally read Law. He became a barrister in 1955, concentrating on family law (‘divorces for the rich’) and art contract law (‘pop stars arguing with their managers’). ‘A time of not much work and lots of money,’ he asserted, although actually it was an increasingly busy and fashionable practice. He was persuaded, however, by his medical advisors to seek quieter waters because of his hypertension. He became first a Recorder and then, in 1980, Judge in the Willesdon County Court. Here, he became aware of the problems arising between Caribbean and white people and those associated with poverty and poor education. While holding this judicial post, he became a President for the Mental Health Revue Tribunals, where we first met, often working at Broadmoor. He was like a breath of fresh air, he had a lovely clarity of thought – right to the point and no nonsense with red herrings. ‘That is not something we can deal with – outside our powers’. He said that was where his awareness and interest in mentally disordered offenders began.

At the same time, his interest in art and things artistic led to numerous committees including at various times Chairmanship of the Friends of the Tate Gallery and the Koestler Award Trust, President of the Royal Literary Fund, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Byam Shaw School of Art, a member of the committee looking after the art archives of the Bethlem Hospital and an inspiration to the Pimlico Opera Company (the producer of inmate operas). His interest in prisoners after the Inspectorate led to Presidency of Unlock, the national association for reformed prisoners. His experience of deafness in two of his children led to his being Chairman of the National Deaf Society. His sense of humour led to his writing the books Great Legal Disasters and Great Legal Fiascos, his experience and scholarship to writing an account of sentencing in Britain, a study which won the Charles Douglas Home Award in 1996.

Stephen enjoyed very good relationships with Home Secretaries Douglas Hurd and Kenneth Baker. However, as he was so outspoken, it was inevitable that he would meet opposition as the political scene changed. It ended with the clashes with Home Secretary Michael Howard, who held ‘differing views’. Stephen's second period as Inspector ended in 1995 and was not renewed. Perhaps his major single improvement was an end to the degrading practice of slopping out ‘years before it was thought possible or even necessary’ to quote the present Chief Inspector. An old inmate said to me during one prison inspection, ‘This place is much better now and it's all down to ’im’. So many people since his death have expressed sadness, even though they might not have met him. He inspired affection.

Sir Stephen Tumim, born 15 August 1930, died of a heart attack on 8 December 2003, while visiting the Galapagos Islands. He is survived by his wife, Winifred, and his three daughters.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.