A few weeks ago, I was tidying my desk at the College when I came across a letter from Bob Kendell. In it, he told me that he would not be standing for re-election to Council because he thought he should be replaced by someone younger. But, he said, he would gladly take on any task we asked of him “provided I think I know enough about the subject”.

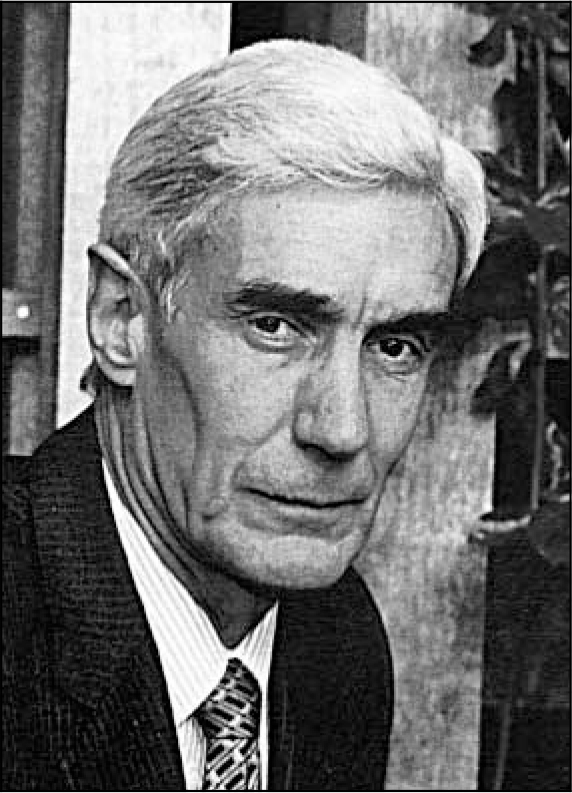

For me, that letter typifies Bob, who sat at the same desk with such distinction as President of the College and who sadly collapsed at his own desk, at home in Edinburgh, just before Christmas. The letter was written in a hand that was as neat and precise as his intellect, yet its content overflows with generosity towards others and humility about his own achievements.

Bob listed “walking up hills” as one of his favourite pastimes and he did so, metaphorically, with skill and determination, throughout his career. He was born in Rotherham but brought up on a farm amongst the slate quarries of the Carnedd mountains of North Wales. People do not choose psychiatry by accident, and early tragedy in Bob's family background had already shaped the humanity with which he approached relationships from there on.

The last thing Bob would have wanted is a roll-call of prizes, but his CV makes formidable reading. From a scholarship to Peterhouse College, Cambridge (double first class honours degree in Natural Sciences, 1956), through King's College Hospital Medical School and house jobs at the King's College, Central Middlesex and Brompton Hospitals and the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in Queen Square, Bob entered the galaxy of 1960s London psychiatry as one of its brightest stars.

He was, successively, Registrar, Senior Registrar, Reader and Honorary Consultant in the Bethlem Royal and Maudsley Hospitals and Institute of Psychiatry circuit (1962-1974) before becoming Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh (1974-1991) and Dean of its Faculty of Medicine (1986-1990). He held temporary academic appointments in the Universities of Vermont, Saskatoon, St Louis, Tennessee, Iowa, New York and in Sweden, Australia and New Zealand; but Bob lived and worked in Edinburgh for over a quarter of a century.

Along the way, Bob picked up the Gaskell Gold Medal in our own College and served as examiner to many other Colleges. He sat on the board of at least six professional journals and produced a string of seminal books, chapters and articles on every key issue in psychiatry, from the philosophy of service to the intricate epidemiology of illness. He was adviser to a host of national and world organisations and was showered with honorary fellowships at home and abroad. He was a Foundation Fellow of both our own College and of the Academy of Medical Sciences and was made an Honorary Fellow in 2000. Appropriately enough, he was made a Commander of the British Empire for services to education in 1992. Bob was Chief Medical Officer for Scotland (1991-1996) and President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (1996-1999) through some of the most turbulent times in politics and the profession, respectively.

So much for statistics. What they reflect is a life-long commitment to four key areas — research, teaching, politics and the practice of psychiatry. There are academic departments across the world who were inspired by the rigour of his inquiry; there are exam students who have blessed the name of Kendell et al; there are audiences whose minds have fizzed for weeks with ideas injected like depots; and there are politicians who have learnt much (sometimes only too painfully) from his insight. Above all, the College, its staff, Officers and members grew to admire and depend upon the strength that he gave us as our first fulltime President at 17 Belgrave Square.

What Bob brought to all these areas was a fascination with his subject, a passionate pursuit of knowledge, a puritan attention to getting the details right, an unwavering moral honesty and the courage to speak his mind, whatever the circumstances. It was a set of qualities sometimes difficult for the rest of us to live up to. Bob did not suffer fools gladly in College committee, Government or taxi-rank. But if you stuck with it, you were rewarded with a wry smile, a hand on the shoulder, a quiet pint over discussion of the arts or a trip to the Andes and, best of all, a delicious snippet of gossip about a former colleague; in short, with friendship.

Bob was an incredibly fit man, in every sense. He would dash off in mid-sentence to run after a bus, jump on its platform and expect you to be there to continue the conversation. He swam his customary 40 lengths the day before he died and was hard at work at his computer the morning he did so. At post-mortem examination, he was revealed to have a brain tumour and his death, at least, spared him a slow physical and cognitive decline that would have been hard for a man like Bob to bear. But it is difficult to believe that he has gone.

Bob leaves a wife, Ann, a consultant anaesthetist and as much a part of the College as he was, four children, Katherine, Judith, Patrick and Harry, one grandchild, Ewan, and “two pending”. He leaves the rest of us the memory of a man at the peak of his powers. Despite what you said in that letter, Bob, you knew a lot about everything. I shall miss your wise counsel. My wife, Mary, misses your wicked sense of fun. And she isn't often wrong about things like that!

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.