Establishment of boundaries, limit setting and safety of patients and staff are important aspects of mental health care delivery, but some psychiatric patients appear unwilling to cooperate when faced with appropriate limits. They may become involved in violence, criminal damage or public order offences. Rates of assault by in-patients against staff are increasing (Reference SchneidenSchneiden, 1993). In NHS hospitals this has been found to range from 0.15 incidents per patient per year in rural settings to 0.60 incidents per patient per year in urban hospital settings (Reference Drinkwater, Gudjonsson, Howell and HollinDrinkwater & Gudjonsson, 1989). A high rate has been confirmed recently among psychiatrists (Reference DaviesDavies, 2001).

One of the strategies that can be effective in limit setting following extreme or persistent challenging behaviour is to refer matters to the police. In this paper we review issues facing the police once referral has been made. We specifically refer to the mechanism used to decide whether a case results in no further proceedings or leads to a caution or prosecution.

Initial considerations

The removal of a patient with known or suspected psychiatric disorder from hospital to a police station is a complex issue and some key points are highlighted here. In cases where an offence is alleged to have been perpetrated in Mental Health Services facilities, staff are likely to be key witnesses and may be asked to act as witnesses or attend court. If an officer has evidence to suspect a person of having committed an offence, then he or she must caution that person and inform him/her of his/her right to a solicitor, according to Section 58 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (Reference ZanderZander, 1995). The officer may go further and arrest the patient. Directions from the Home Office (1995) suggest that this is possible even for patients who are detained under the Mental Health Act 1983. Risks to the health and safety of the patient have to be balanced against risks to the safety of staff and other patients remaining on the ward.

When a patient is taken under arrest to the police station, an examination by the forensic medical examiner will determine whether he or she is fit to be detained and fit to be interviewed, according to Section 66 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (Reference ZanderZander, 1995). An appropriate adult, as defined in the Act (Code of Practice C), may be needed to support and advise the patient. The psychiatric team can provide relevant information on a ‘need to know’ basis, having regard for confidentiality issues (Reference BeckBeck, 1990; NHS Executive, 1997).

Evidence and public interest

Following referral of the case, the police will gather evidence in relation to the alleged offence. A decision is made as to whether prosecution is in the public interest. Relevant factors that need to be considered include the age and mental health of the offender, the relationship between offender and victim, any element of corruption, the attitude and wishes of the victim and the likely outcome of the case (Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure, 1980).

The Police Case Disposal Scheme

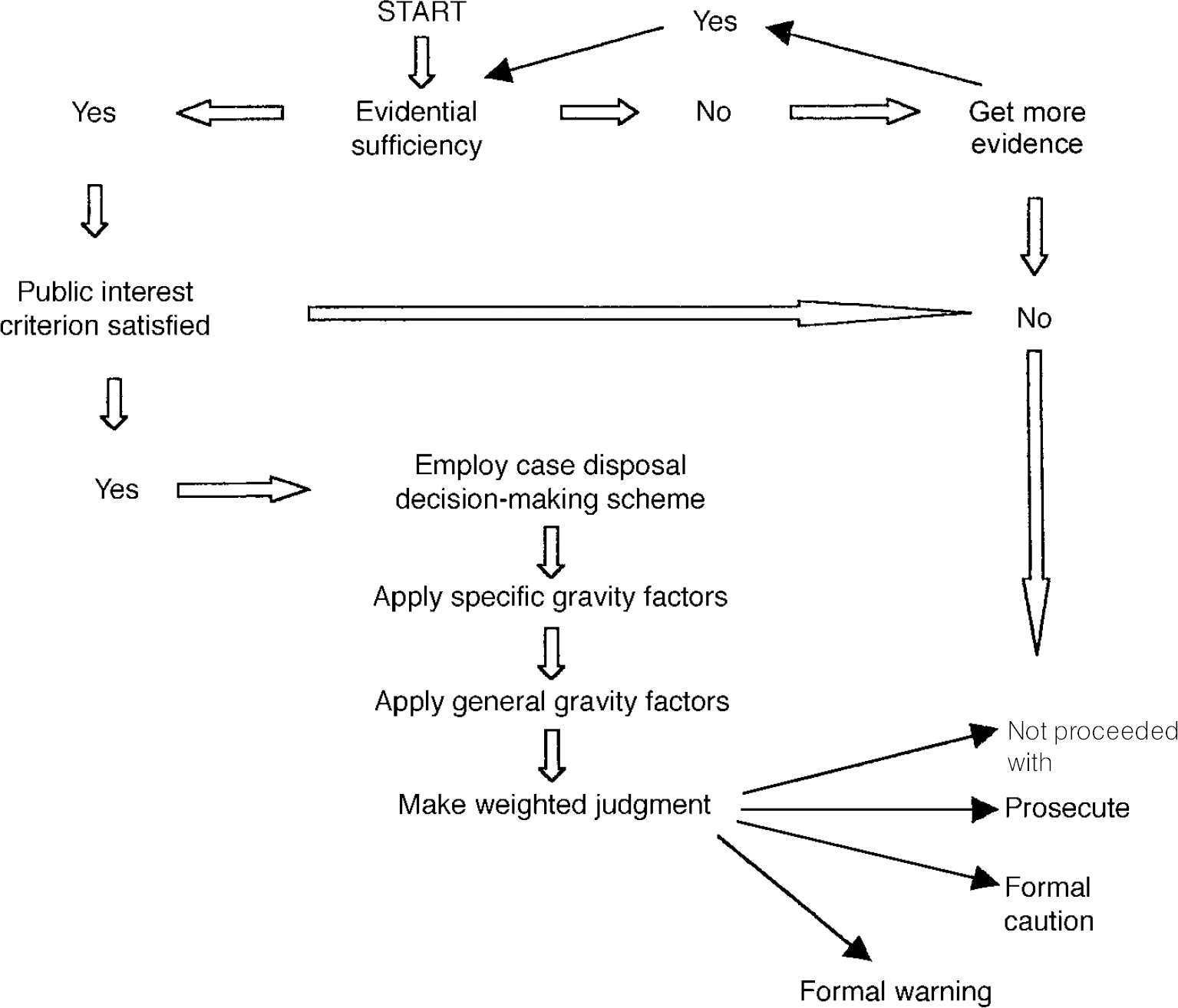

When there is sufficient evidence and prosecution is considered to be in the public interest, police officers will apply the Police Case Disposal Scheme outlined in Fig. 1. Application of the scheme is not mechanistic and relies on the experience and judgement of the investigating officer.

Fig. 1 Police Case Disposal Scheme

The first step in employing the scheme is to allocate a case disposal option number. Table 1 presents disposal option numbers, together with their implications. Specific offences are associated with specific disposal option numbers. For example, a charge of actual bodily harm is associated with disposal option number 3, which indicates that the outcome of this charge is ‘pivotal’ on the circumstances and could terminate either with a caution or prosecution. The charge of ‘grievous bodily harm with intent’ is linked to option number 5 — prosecution will always occur for this offence (see Table 1).

Table 1. Police disposal options

| Disposal option no. | Relevant option |

|---|---|

| 1 | Formal warning or not proceeded with |

| 2 | High probability of a caution. Decision-maker needs to be able to justify decision not to caution |

| 3 | Pivotal. The particular circumstances of offences and offender and any aggravating or mitigating factors will determine whether the disposal moves up or down |

| 4 | High probability of prosecution. Decision-maker needs to be able to justify decision not to prosecute |

| 5 | In normal circumstances this will always result in prosecution. Mitigating gravity factors are unlikely to affect the decision to prosecute |

Police disposal numbers only indicate general directions with respect to disposal. The final disposal of the case is determined only after specific and general crime gravity factors have been considered.

Specific crime gravity factors (Table 2) consist of a mixture of intent and actual damage inflicted. They are considered in cases involving assaults, public order and criminal damage offences. Reduction of gravity (and therefore disposal option number) is considered in cases where the offence is an isolated incident with minimal or superficial damage. Impulsivity, response to provocation and no risk of escalation may also lead to a lower disposal option number.

Table 2. Specific gravity factors of some common crimes

| Offence | Increase option no. | Decrease option no. |

|---|---|---|

| Assaults | ||

| Grievous bodily harm with intent | Planned attack | Single blow |

| Use of offensive weapon | Unplanned | |

| Aggravated bodily harm | Sustained attack | One blow |

| Deliberate kicking | Minor injury | |

| Major injuries | Impulsive act | |

| Common assault | Injury caused | Minor assault |

| No provocation | Minor injury | |

| Group action | Impulsive act | |

| Deliberate attack | One blow | |

| Public order offences | ||

| Threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour | Premeditated | Single offender |

| Risk of escalation | Isolated incident | |

| Busy public place | Impulsive action | |

| Criminal damage offences | ||

| Arson (life not at risk) | Deliberate act | Impulsive action |

| Criminal damage (life not at risk) | Serious damage | Minor damage |

| High value | Low value | |

| Deliberate | Provocation | |

| Threat to destroy or damage | Potential damage of high value | Potential damage of low value |

Specific gravity factors that may increase the disposal option number are premeditation, deliberate actions, vulnerable victims, prolonged attacks, extensive injuries/damage, use of weapons, deliberate fire-setting and group offences. With respect to public order offences, an important factor is the extent to which the victim was put in fear.

General gravity factors (Table 3) consider the circumstances of the offender and the victim and the general circumstances surrounding the particular crime. Many of these overlap with factors relevant to the public interest criterion. An important general gravity factor is the state of health of the offender and, importantly, his or her mental health. This may also lead to a reduction in the disposal option number. The psychiatrist may need to advise the police with respect to this. Aggravating factors lead to an increase in the disposal option number and therefore to increasing likelihood of prosecution.

Table 3. General gravity factors

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

|

|

Weighted judgement

A weighted judgement is made after gravity factors have been applied. This judgement leads to the disposal of the case. Options for disposal are as follows: not to proceed with, to formally warn, to caution or to prosecute.

Case example

The consultant psychiatrist on-call was telephoned at night by the duty senior house officer, who had been assaulted by Mr A., a 25-year-old patient with a diagnosis of an emotionally unstable personality disorder (borderline type). Prior to the incident, Mr A. had requested from a staff nurse and then demanded from the ward manager to be transferred back to the ward he had been on during his previous admission. His reasons were that he missed his friends on the other ward and was opposed to attending occupational therapy and other groups that were part of a firm treatment regimen on his current ward. Mr A. became very angry when a bottle of vodka was found in his possession. He became threatening to nursing staff and then to the ward doctor. It became clear that he was likely to assault a member of staff. While the control and restraint team were being called, he ran into the office, punched the doctor in the face and then barricaded himself in his room.

Two hours later, the threat of further violence had been contained. Rumours had spread that Mr A. had assaulted a doctor and stabbed another patient some years ago in another hospital. The nurses, through the on-call doctor, ask if the patient can be charged with the assault. The consultant considers the patient to be fit for interview by the police and agrees for the case to be referred to the police.

When the police officers arrive, they take witness statements from the victim and witnesses. After interviewing the patient, he is arrested, taken to the police station and interviewed in the presence of an appropriate adult. It is decided that prosecution is in the public interest because this is a serious unprovoked assault on a member of hospital staff. The patient eventually is charged with common assault contrary to Section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988.

The officer in charge of the case uses the case disposal scheme as follows. The charge attracts disposal option number 3. Disposal is pivotal on the particular circumstances of the offence and how they are viewed by the police. Should the disposal option number be lowered by the circumstances of the incident, the end result is that the patient will receive a caution. However, if there are more positive specific or general gravity factors, the disposal option may be raised and the patient will face a higher probability of prosecution.

Specific gravity factors that weigh in favour of prosecution are that the patient showed deliberate aggression without provocation and that it was by luck alone that the injuries were not more serious. Negative specific gravity factors are also present because this was a relatively minor assault that caused only superficial damage and is claimed by the patient to be an impulsive act. There was only one blow to the doctor, as opposed to a sustained attack. The combination of positive and negative specific gravity factors has not clarified whether the disposal option number should be increased or decreased, therefore the police officer needs to consider the general gravity factors in this case.

The general gravity factors that make the prosecution more likely are that the offence had an impact on the victim and took place against a victim in public service. The major negative general gravity factor is that the offender has a mental disorder that has affected his judgement and led to the violent assault. The officer would have to decide how significant the mental disorder was. He was guided initially by the medical and nursing staff, who explained that a patient with an emotionally unstable (borderline) personality disorder is still able to make judgements about what is right and what is wrong.

The police also established that 2 years ago the patient, after discharge from a geographically distant mental health service, had indeed returned to assault (but not stab) a patient and a doctor, causing bruising. On the previous occasion a decision had been taken to caution and not to prosecute the patient. The police officer now has another strong positive general gravity factor and, furthermore, is concerned that this offending behaviour, although sporadic, may be repeated. A weighted judgement now leads to the option number being increased to 4 and a recommendation that prosecution should proceed.

Discussion

Home Office (1990) policy in the UK favours the provision of care and treatment rather than punishment of mentally disordered offenders. Although difficulties have been identified in its implementation (Reference FarrarFarrar, 1996), we consider that such a general direction is both desirable and necessary in order to prevent the stigma of mental illness or mental disorder (Reference ByrneByrne, 2000) being compounded by the stigma of criminalisation.

A balance has to be struck. Failure to prosecute in appropriate cases may lead to loss of an opportunity to establish and document dangerous behaviour. The use of part three of the Mental Health Act 1983 remains an important device in striking this balance. It acts as a permanent reminder of the patient's offending. Not only is this vital for future risk assessment, but it imports a qualitative distinction to the management of the patient as well as helping to prioritise the allocation of resources.

Implementation of the Police Case Disposal Scheme in practice involves a series of complex judgements by police officers. This is even more complex in the case of psychiatric patients. Eastman & Mullins (Reference Eastman and Mullins1999) have suggested that criminal acts committed by patients with a mental disorder or a psychiatric history have less chance of being investigated by the police. Good communication and use of opportunities for joint training between mental health staff and police officers may reduce this complexity and assist in better implementation.

Comment

The case example presented in this paper is fictional but faithfully reflects clinical reality. Any resemblance to an actual case is purely coincidental.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Inspector Bruce Frenchum of the Community Safety and Partnership Policy Unit, Metropolitan Police, London, for his advice. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not those of the police.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.