The MacLean Committee was established in 1999 by the Scottish Office to review and make recommendations concerning the sentencing of serious violent and sexual offenders, including those with personality disorder. It provides an alternative perspective on the problem of offenders with personality disorder to that of the Home Office and Department of Health (1999) for England and Wales. It principally recommends:

-

(a) Special sentencing — an order for lifelong restriction — for offenders likely to pose a continuing and serious risk to the public.

-

(b) New mandatory procedures for the assessment of risk.

-

(c) Establishment of a risk management authority.

-

(d) Special sentencing for mentally disordered offenders likely to pose a continuing and serious risk.

The MacLean Committee (Scottish Executive, 2000) was established in March 1999 by the UK Government, with the following remit:

-

• To consider experience in Scotland and elsewhere and to make proposals for the sentencing disposals for, and the future management and treatment of, serious sexual and violent offenders who may present a continuing danger to the public, in particular:

-

• to consider whether the current legislative framework matches the present level of knowledge of the subject, provides the courts with an appropriate range of options and affords the general public adequate protection from these offenders

-

• to compare practice, diagnosis and treatment with that elsewhere, to build on current expertise and research to inform the development of a medical protocol to respond to the needs of personality disordered offenders

-

• to specify the services required by this group of offenders and the means of delivery

-

• to consider the question of release/discharge into the community and service needs in the community for supervising those offenders.

-

The Committee reported in June 2000. This paper describes the main proposals, discusses their implications for forensic psychiatry in Scotland and compares them with proposals for ‘dangerous people with severe personality disorder’ in England and Wales.

Background

In several countries there has been concern about offenders who have committed serious violent or sexual offences where there is felt to be a continuing risk of further offending (Reference Heilbrun, Ogloff and PicarelloHeilbrun et al, 1999). In England and Wales a ‘third way’, involving institutions half-way between secure psychiatric hospitals and prisons, for dangerous people with severe personality disorder (Home Office and Department of Health, 1999; Home Affairs Select Committee, 2000) has been criticised by psychiatrists (Reference ChiswickChiswick, 1999; Reference MullenMullen, 1999; Reference GunnGunn 2000) and the Health Select Committee (2000).

There has sometimes been a mistaken assumption that psychopathic disorder does not exist in Scottish legislation. Although the label ‘psychopathic disorder’ does not appear, the same category exists, with virtually identical criteria to those used in England and Wales (Reference Darjee, McCall-Smith, Crichton and ChiswickDarjee et al, 1999). The difference between Scotland and England has been in practice rather than in law: since the early 1980s offenders with primary personality disorders have not been recommended for psychiatric disposals in Scotland. Most serious violent and sexual offenders receive determinate prison sentences and a small number will receive a discretionary life sentence. The disposals available for mentally disordered serious offenders in Scotland are almost identical to those in England and Wales (Reference ChiswickChiswick, 1997). Many such offenders will suffer from personality disorder in addition to their primary mental disorder, but primarily offenders with personality disorder do not receive hospital disposals.

The recommendations of the MacLean Committee

The Committee concluded that special sentencing arrangements were necessary for high-risk offenders; those convicted of serious violent or sexual offences (or exceptionally less serious charges) who, because of their circumstances are likely to pose a continuing risk to the public. To give an estimate of the size of the problem, in Scotland during 1998 50 people who had previously been convicted of a similar offence were imprisoned for a violent sexual offence.

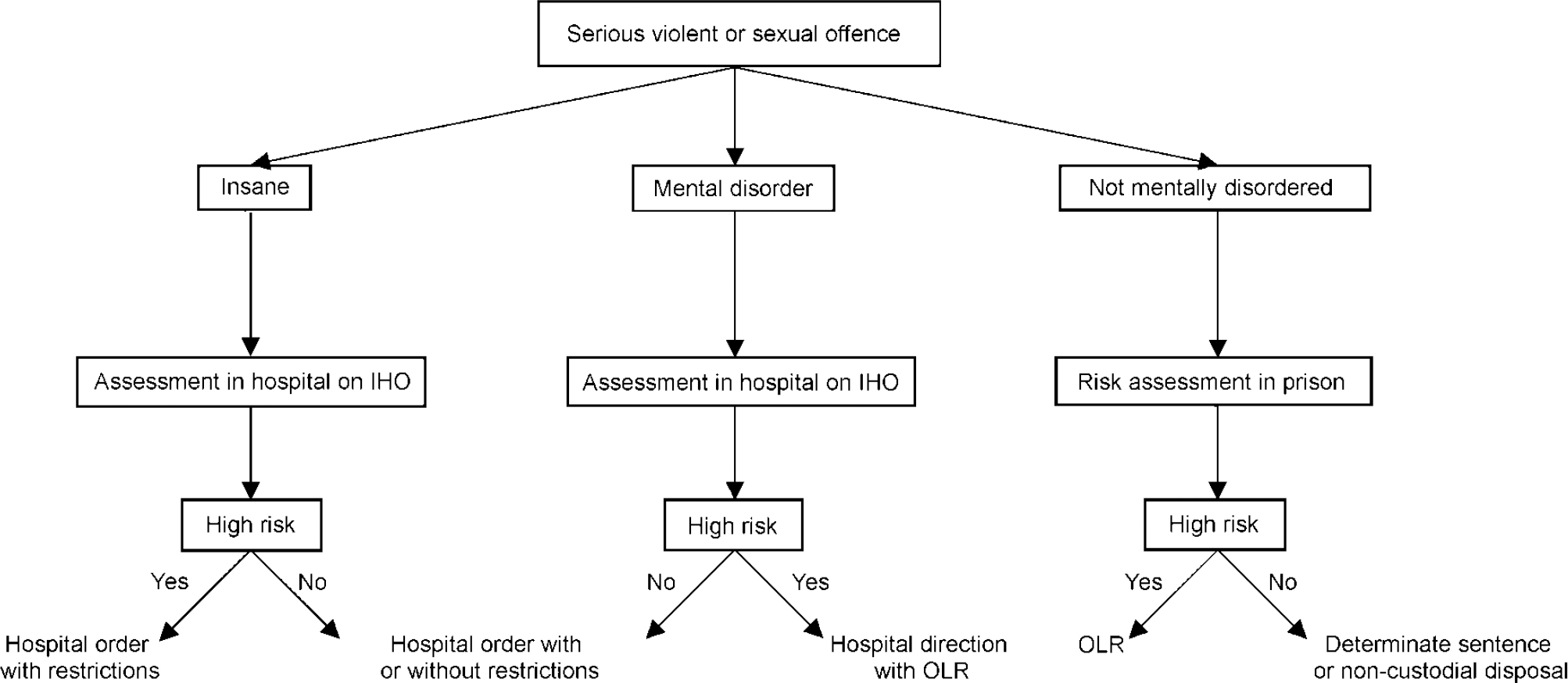

The Committee proposed the establishment of an ‘Order for Lifelong Restriction’ (OLR) for such offenders, which could only be imposed by a senior Scottish court after a period of formal risk assessment. The assessment of serious violent and sexual offenders set out in the MacLean Committee proposals is summarised in Fig. 1. After a tariff for the offence had been served, release would be dependent on the level of continuing risk of serious recidivism. Offenders would be released on licence, subject to conditions intended to reduce risk and recall to prison if those conditions are not met.

Fig. 1 The assessment of high-risk offenders in Scotland, proposed by the MacLean Committee (Scottish Executive, 2000). IHO, interim hospital order; OLR, order for lifelong restrictions. ‘Mental disorder’ refers to an individual suffering from mental disorder of a nature or degree that makes it appropriate for him or her to receive medical treatment in hospital (Section 17(1)(a) Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984. ‘Insane’ refers to an individual found insane in bar of trial or acquitted of the offence on the grounds of insanity.

Key to the proposals is the establishment of a Risk Management Authority (RMA), who would establish and disseminate best practice information regarding risk assessment and management; commission research; accredit the centres tasked with formal risk assessments; set training standards for those involved in assessments; agree a risk management plan that must be prepared for each OLR; and commission appropriate risk management services. While in custody the risk management plan would include security classification and therapeutic programme and would be reviewed regularly by the RMA. Release from custody or recall would be the responsibility of the Parole Board, operating through the Designated Life Tribunal (DLT), who would set licence conditions that would form the basis of a community risk management plan.

In the community there would be specialist services for high-risk offenders, and intensive supervision and surveillance. Components of this might include: electronic monitoring, announced and unannounced visiting, alcohol and drug testing, strict conditions regarding place of residence and participation in treatment and rapid and predictable return to conditions of greater security in the event of non-compliance.

The proposals also apply to mentally disordered serious offenders, who would currently be placed on restricted hospital orders. High-risk offenders with mental disorders who may require treatment in hospital would be assessed in a secure psychiatric hospital on an interim hospital order. There would be an assessment of whether the offender was high risk and/or requiring treatment in hospital for mental disorder. If they were both, then they would receive an OLR with a hospital direction (Section 59a, Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995); this is Scotland's ‘hybrid order’, which combines a period of hospitalisation with a prison sentence. A hospital order with restrictions would not be available in such cases unless the offender was found ‘insane’ either in bar of trial or at the time of the offence.

In their terms of reference, the Committee was required to give special consideration to offenders with personality disorder. They concluded that a third way approach in Scotland would be neither feasible nor advantageous and that if offenders with personality disorders are assessed as high risk they should be managed along the lines recommended for other high-risk offenders.

Discussion

Previous reports in this area have recommended the introduction of indeterminate sentences for certain dangerous or high-risk offenders with personality disorders (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975; Reference Fallon, Bluglass, Edwards and DanielsFallon et al, 1999). The current English and Welsh proposals depend on a psychiatric diagnosis; preventive detention can be applied where no offence has been committed or a sentence tariff has been completed. By concentrating on risk posed by new serious offenders rather than those of a particular diagnosis, the MacLean proposals avoid many of the ethical concerns raised over English and Welsh proposals (Reference MullenMullen, 1999). The House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee (2000) was critical of the English proposals and recommended that the Scottish approach should be adopted “to make clear that they are concerned with offending behaviour and not with mental disorder”.

Risk assessment is central to the MacLean proposals. The Committee favoured structured clinical assessment along the lines of Historical, Clinical and Risk, 20 items (HCR-20) (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997) over an actuarial approach (e.g. the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG); Reference Quinsey, Harris and RiceQuinsey et al, 1998) that was considered inflexible, unable to inform risk management and difficult to apply in court. It should be noted that neither the VRAG nor the HCR-20 has been validated in a Scottish sample. Such research in Scotland is recommended by the Committee.

High-risk offenders with mental disorders will only receive a restricted hospital order if they are found ‘insane’ at the time of the offence or in bar of trial. Otherwise high-risk mentally disordered offenders will be placed on a hospital direction with a sentence tariff and potential indeterminate detention in prison. The Scottish hospital direction has only been used four times, but a majority of forensic psychiatrists in Scotland favour its use in cases where antisocial personality disorder coexists with mental illness that is brief or unrelated to offending (Reference Darjee, Crichton and ThomsonDarjee et al, 2001). It is unclear whether psychiatrists in Scotland would currently favour replacing the restricted hospital order by the hospital direction with OLR in cases where there is a sole diagnosis of mental illness. The concerns raised regarding the hospital direction (Reference EastmanEastman, 1997; Reference ThomsonThomson, 1999) can therefore be applied to these proposals. An alternative solution would be to simply apply the risk assessment process and post-discharge supervision arrangements envisaged for OLRs to restricted hospital orders, but this would have gone beyond the remit of the Committee.

To avoid OLRs, there may be an increased use of the ‘insanity defence’ in Scotland; as in England and Wales, this is rarely used at present. It is unclear whether the restricted hospital order will have any role in non-high-risk cases. It should only be applied if there is a real difference between the criteria used to decide high risk and those to decide the appropriateness of restrictions. If not, the restricted hospital order will no longer be the major disposal for mentally disordered serious offenders in Scotland. If so there will be two tiers of indeterminate disposal for mentally disordered offenders. This potential double jeopardy is avoided in non-mentally disordered cases since it is proposed that those not satisfying high-risk criteria cannot be made subject to a discretionary life sentence.

The effect of the MacLean proposals would change the landscape of Scottish forensic psychiatry and affect the management of many people with mental disorders who commit serious offences. Much rests on the ability of the RMA to commission appropriate services, training and research. The emphasis in Scotland is clearly on offences and offenders rather than on psychopathic disorder or severe personality disorder. The MacLean proposals offer an alternative approach that is worth considered scrutiny beyond the borders of Scotland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.