Clinical attachments are an essential step in the process by which international medical graduates (IMGs) secure training posts in the UK. Although the British Medical Association (BMA) provides general guidelines for clinical attachments, the current system lacks a structured process regarding selection, defined length of posts, predetermined contents of training and detailed guidance for consultants supervising clinical attachments in psychiatry. This article outlines the experience in Nottingham of developing a formalised clinical attachment scheme and includes the lessons learnt and difficulties faced during the process. Also presented are the results of feedback surveys from consultants and IMGs who have partaken in the new formalised scheme.

International medical graduates are a proven asset for the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, with an estimated 22140 overseas doctors working in the English NHS alone (Department of Health, 2003). The recent success of IMGs has prompted a large influx of inexperienced overseas doctors seeking postgraduate medical training in the UK. Recent changes in regulations for employment of non-European Economic Area (EEA) doctors in training posts (Department of Health, 2006) have meant that fewer such doctors will be applying for clinical attachments in the future. However, local experience has shown that there will still be significant demand for these placements from doctors on spouse-dependent visas and those from EEA countries.

It is virtually impossible for an IMG to obtain a training post in the UK without spending some time in a clinical attachment. The BMA defines a clinical attachment as

‘a period of time when a doctor is attached to a clinical unit with a named supervisor with the broad aims of gaining an appreciation of the nature of clinical practice in the UK and observing the role of doctors in the NHS’

A clinical attachment serves two basic purposes. First, it allows IMGs to gain an understanding of the mechanics of the NHS and the medical, legal and cultural traditions of the UK. Second, an attachment enables IMGs to obtain a reference from a UK consultant prior to job application.

Current situation

Currently IMGs who wish to undertake a clinical attachment contact consultants directly, hoping to find a consultant who has sufficient time and willingness to offer a placement. Although there are some general guidelines and advice for clinical attachments (British Medical Association, 2001; Reference Berlin, Cheeroth and AgnellBerlin et al, 2002; Reference PrabhuPrabhu, 2004; Reference MahboobMahboob, 2005), there is currently no structured selection process. The content of training and the length of these placements remain undefined, with only limited guidance for the supervising consultants (Turya, 2004).

This situation, which has continued for years, has been amplified by the recent expansion in IMG numbers. Consultants and medical staff are now inundated with large numbers of requests for clinical attachments. Although it is anticipated that this demand will reduce, it is not thought that it will disappear altogether.

Outside the UK and in other specialties there have been some previous attempts to formalise clinical attachments. The Australian pre-employment programme (Reference Sullivan, Willcock and ArdzejewskaSullivan et al, 2002) and the London deanery scheme for refugee doctors (Reference Ong and GayenOng & Gayen, 2003) have met with great success and have resulted in a more integrated, confident and functional workforce.

Local experience: Nottingham

A postal survey of 32 consultant psychiatrists in Nottinghamshire was conducted to assess existing attitudes towards clinical attachments (Reference White, Malik and BagalkoteWhite et al, 2005). The survey revealed lack of resources as a significant hindrance to the success of clinical attachments. Underlining this point, 25 respondents (78%) identified a centralised recruitment process as key to a successful clinical attachment scheme. The importance of resources such as a trainer induction pack was also highlighted by 26 respondents (81%).

Results from the survey combined with input from medical staffing and postgraduate education departments prompted the development of a formalised scheme for clinical attachments.

Formalised clinical attachment scheme

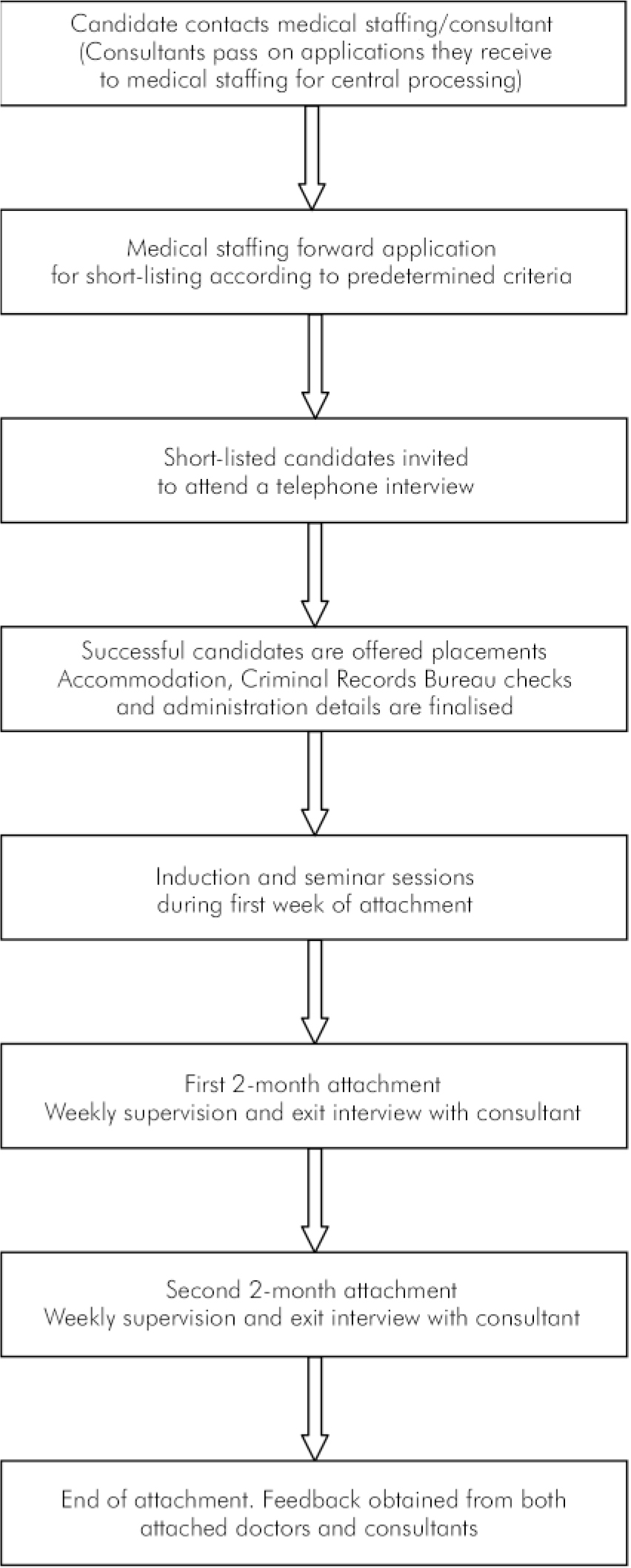

An overview of the scheme is shown in Fig. 1.

Selection

Short-listing

All applications received by consultants are forwarded to the medical staffing department for central processing. Applicants are sent a standard letter informing them of the new programme and the relevant time scales. The medical staff in the clinical attachment working group (a College tutor, a specialist registrar (SpR) and a senior house officer (SHO)) then shortlist candidates according to the following predetermined criteria:

-

• a pass in the Professional Linguistic Assessment Board (PLAB) 2 examination (unless the candidate is exempt)

-

• evidence of a genuine interest in psychiatry

-

• less than 6 months previous clinical attachment experience

-

• provision of two referees (not necessarily UK-based).

Interviews

An initial cycle of face-to-face interviews proved to be inconvenient and expensive for both the applicants and the trust. The selection process is therefore now conducted by standardised 10 min telephone interviews. The panel consists of a college tutor, two trainees and a medical staffing advisor. Areas covered during the interview include those related to the applicant's career path to date, career objectives and commitment to psychiatry. The candidate is also given a clinical scenario that aims to assess their judgement in a real-life situation.

Structure

Overview

The successful applicants are offered two placements with different consultants, each lasting 2 months. Effort is made to ensure that one placement is with a general adult psychiatrist and the other with an old age psychiatrist. This not only allows each candidate to gain experience in two sub-specialties but also presents the opportunity to obtain two references from NHS consultants.

Correspondence, organisation of interviews, completion of Criminal Record Bureau checks, coordination of accommodation and allocation of placements are dealt with by the medical staffing department. The induction process and the seminar sessions (outlined below) are coordinated by the postgraduate department.

Induction

The scheme operates on a 4-monthly cycle in line with foundation year 1 posts. This allows attached doctors to attend the trust's foundation-post induction programme that includes topics such as history-taking, self-harm assessment, rapid tranquilisation policy and the Mental Health Act 1983.

In addition, specific handbooks are distributed to each attached doctor during the induction process. These detail the aims and requirements of the scheme and provide both local and generic information about living in the UK. Consultants who accept an attached doctor are each given a handbook for trainers that provides relevant information and guidance.

Seminar sessions

Six seminar sessions have been developed with the aim of providing teaching on relevant topics for IMGs who intend to work in the UK. Seminar sessions are run by SpRs and experienced SHOs who have expressed an interest in teaching. These are delivered within a day at the start of each 4-monthly cycle.

Mentorship

Each attached doctor is allocated a volunteer SHO mentor who acts as a ‘ friendly face’, providing practical information and guidance about working in the NHS, applying for jobs and managing career progression in general.

Accommodation

Single accommodation is provided to attached doctors on trust premises for the duration of their attachment.

Fig. 1. Overview of the scheme.

Feedback

We are currently recruiting for our third cycle of attached doctors, with four IMGs being placed with each recruitment cycle. All attached doctors complete formalised written feedback questionnaires upon completion of the scheme. To date, all attached doctors have given positive feedback about the selection process, the induction, the handbook and the level of clinical exposure and supervision. Feedback about the teaching seminars resulted in practical changes in their delivery, and the mentorship programme was reported as being inconsistent, with wide variations in mentor-mentee contact.

All attached doctors were offered short-term locum posts within the trust and all reported that this further developed their experience. One attached doctor was appointed on an SHO training scheme, whereas others have secured substantive SHO posts for 6 months.

Participating consultants also completed feedback questionnaires and reported that they were able to provide significant clinical experience for attached doctors but this, together with weekly supervision sessions, resulted in a moderate increase in time pressures. They also reported that the trainer's handbook was helpful and they valued the centralised selection and administrative support that the scheme provided. Positive feedback was also received via a recent postgraduate deanery accreditation visit.

Difficulties faced and challenges for the future

-

• There was, and continues to be, no incentive other than goodwill for consultants to take on clinical attachments.

-

• Some attached doctors left the scheme as they managed to secure a paid position. We found that it is useful to have a backup list of IMGs to ensure that the scheme is utilised to its optimal level.

-

• Organisation of induction, seminar days, short-listing and interviews were an added commitment for the medical and non-medical staff involved.

-

• Funding for the programme is dependent on the trust's wider strategy on recruitment and postgraduate training.

-

• Future clinical attachment schemes will have to take into account the changing demographics of applicants resulting from the new immigration regulations for non-EEA doctors.

Conclusion

Despite new regulations regarding training visas for IMGs, there will always be a demand for clinical attachments. It would be prudent to have national guidelines, central funding for a defined number of placements and incentives for consultants, college tutors and trusts to take on these attachments.

The Nottingham clinical attachment scheme's trainee and trainer handbooks have been submitted for review to the Royal College of Psychiatrists Overseas Doctors Training Committee. We hope that the Nottingham experience can be used to inform other mental health trusts in setting up equivalent schemes in other areas of the country.

Declaration of interest

All the authors have been involved in the development of the clinical attachment scheme in Nottingham. A.M. is an IMG who started his career in the UK via a clinical attachment.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.