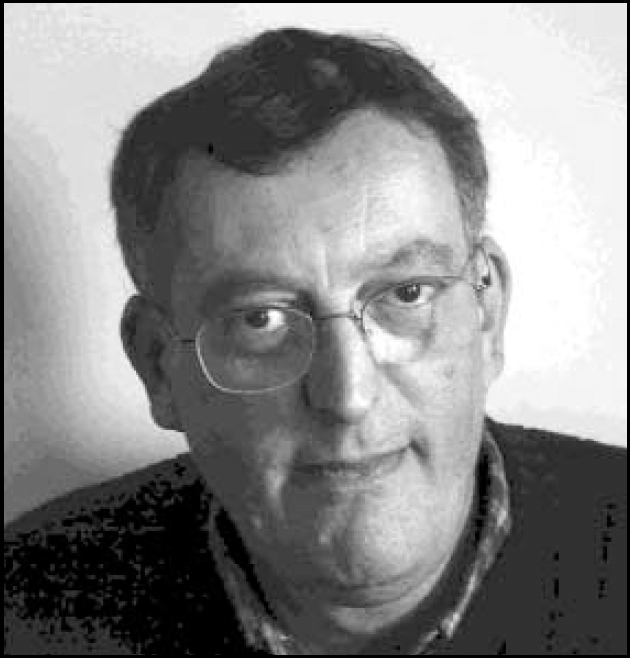

Dr Frank Holloway is Consultant Psychiatrist and Clinical Director, Croydon Integrated Adult Mental Health Service, South London and Maudsley NHS Trust. He trained at King's College Hospital, London. His special interests are in Rehabilitation and Community Psychiatry and mental health services research.

If you were not a psychiatrist, what would you do?

I doubt if I would have made much of a success of any other branch of medicine. Had I not been able to change from my natural sciences degree to medicine I would have pursued a career in academic psychology. Where that would have led in the long term I don't know.

What has been the greatest impact of your profession on you personally?

In practical terms it has meant living in London, compromising the family's quality of life for the sake of my career.

What are your interests outside of work?

Books and good food.

Who was your most influential trainer, and why?

Robert Cawley, our professor, was certainly the scariest. Griffith Edwards, an enormously erudite man, was the most fun to work for. JohnWing, who was my research supervisor, was probably the most significant. He encouraged my interest in looking at the way mental health services work and, I now think, provided me with most of the intellectual toolkit that I now use. I've always regretted that his research skills didn't rub off on me.

What job gave you the most useful training experience?

My first year as a senior registrar (as we were in those days). The step up in responsibility was chastening. Supporting the more junior trainees was deeply rewarding.

Which book/text has influenced you most?

Institutionalism and Schizophrenia. This book, written by John Wing (a psychiatrist) and George Brown (a sociologist), was published in 1970 and was one of a series of texts produced by the Medical Research Council Social Psychiatry Unit in the 1960s and 1970s. It is an as yet unparalleled example of the value of interdisciplinary research in psychiatry.

What research publication has had the greatest influence on your work?

Undoubtedly Stein and Test's 1980 paper in Archives of General Psychiatry, which introduced the PACT [psychiatric assertive continuing care team] model (Stein, L.I. & Test, M.A. (1980). Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I, Conceptual model, treatment programme and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 392-397). Much of my clinical, managerial and research activity has involved following up the questions raised by this study into what we now call assertive community treatment. Sadly, they obtained better results than I from this intriguing innovation.

What part of your work gives you the most satisfaction?

Two things. Firstly, finding solutions to problems that are causing difficulty or distress that others haven't been able to see. Secondly (and selfishly), writing things that people might read and enjoy.

What do you least enjoy?

Dealing with complaints against me or, as a Clinical Director, colleagues.

What is the most promising opportunity facing the profession?

It's clear there aren't enough of us. Logically, this should result in an expansion of both training grades and consultant numbers.

What is the greatest threat?

Because there aren't enough of us, the standard of care that we can reasonably provide falls rather far below the optimum. This erodes our credibility.

What single change would substantially improve quality of care?

There are three possible options; less people are referred to secondary mental health services and identified as their continuing responsibility; secondary mental health services and social care receive significantly increased resources; or our treatment technologies improve very markedly in their effectiveness, decreasing the burden of continuing care.

What conflict of interest do you encounter most often?

I don't experience any clear-cut ‘conflict’ of interest. Psychiatry is always, and rather particularly, about balancing interests (those of the patient, carers, society at large, managerial and Government priorities, other patients who are competing for limited resources, the capacities of the care team, one's own coping capacities). It is important for the practitioner to be aware of this process.

Do you think psychiatry is brainless or mindless?

It is clear that our sister discipline of neurology is largely ‘ mindless’. Psychiatry is a pragmatic discipline that has always drawn on contemporary and unsatisfactory understanding of brain and mind. I worry that psychiatry continually repeats the error of being prematurely ‘ brainful’ and, a particular risk in the brave new genomic era, ‘ genefull’.

How would you entice more medical students into the profession?

It is easier to see how we can put people off. We can choose students purely on the basis of their excellence at passing science A-Levels, rush them through an overloaded curriculum that includes a parodic account of behavioural sciences for two years and then expose them to psychiatry in a chaotically organised block with neurology and ophthalmology as their first real exposure to patients.

What is the most important advice you could offer to a new trainee?

Don't panic, take your time and listen to the relatives (even if they appear irritating they may well be right).

What are the main ethical problems that psychiatrists will face in the future?

We are facing an unprecedented attack on the rights of patients to confidentiality. The proposed new Mental Health Act, with its broad definition of mental disorder, may require psychiatrists to legitimate the incarceration of people identified as ‘dangerous’, for whom we have no effective treatment.

How would you improve clinical psychiatric training?

Alter the MRCPsych curriculum to ensure that trainees have demonstrated competencies in psychological treatments, mental health law and psychiatric ethics before achieving Part II. Get rid of the ‘research day’ for specialist registrars, who should have four days a week working within a clinical team with two sessions to pursue either a clear-cut supervised research project or to undertake special interest sessions.

What single change to mental health legislation would you like to see?

I am not clear that the case for change in the Mental Health Act 1983 has been made. Most psychiatrists would applaud an abolition of Mental Health Act Managers, who take up a lot of medical time but do not add obvious value to patient care.

How should the role of the Royal College of Psychiatrists change?

I believe it is on the right track. The College needs to form strong links with other interest groups, particularly users and carers. It needs to maintain and monitor professional standards. It needs to give the entire membership a feeling of belonging.

What is the future for psychotherapy in psychiatry training and practice?

It is vital that psychiatrists have demonstrable competencies in psychological treatments: without this, future psychiatrists will completely lack credibility.

What single area of psychiatric research should be given priority?

As someone whose expertise and interest is in health services research, it pains me to say that aetiological research logically deserves primacy.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.