Antipsychotic-induced obesity carries serious physical and psychological implications. However, little data are available on management of this problem. People with schizophrenia are vulnerable to several physical conditions, including type II diabetes, cardiovascular disorders and the metabolic syndrome (Reference Ryan and ThakoreRyan & Thakore, 2002). Lifestyle elements such as poor diet, cigarette smoking, heavy alcohol use and sedentary lifestyle (Reference Brown, Birtwistle and RoeBrown et al, 1999) predispose to ill health. Treatment with antipsychotic medication, which is associated with weight gain in a significant proportion of patients (Reference Allison, Mentore and HeoAllison et al, 1999), exacerbates the risk and stigma associated with schizophrenia. Indeed antipsychotic-induced weight gain has been identified as a cause of non-adherence to treatment regimes (Reference Nasrallah and MulvihillNasrallah & Mulvihill, 2001; Reference RecasensRecasens, 2001).

Little data are available about the response of patients with schizophrenia who are overweight to psychosocial weight management interventions. We now evaluate such an intervention in overweight (body mass index (BMI) >25) individuals treated with antipsychotics.

Method

The South London and Maudsley Ethics Committee granted local ethics approval to formally audit the service.

We invited patients who were overweight, and wanted to lose weight, to participate in a weight management programme. Patients self-referred, or were referred to the service through their primary clinical teams. Patients were in- and out-patients of the South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Trust (catchment population 520 000).

The service inclusion criteria were: DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar illness; stably maintained on antipsychotic treatment; overweight (BMI > 25); and agreeable to participation in a weight management programme.

The exclusion criteria were: concomitant diagnosis of eating disorder, learning disability or substance misuse; and any physical problem (particularly cardiac) that might preclude participation in a weight management programme.

After screening, 44 patients were included. One patient did not meet the above criteria (BMI <25) but was included because of significant weight gain above her baseline (approximately 18 kg) and an abnormal waist-hip ratio. This patient was highly motivated to access the service.

Treatment package

A registered mental and general nurse trained in nutrition and diet theory ran the service. Patients were assessed at a screening interview. They were given a self-report ‘diet diary’ to complete, recording all food and drink consumed over the following week. Patients were seen within a fortnight, the ‘diet diary’ discussed and an individualised diet plan dispensed. They had advice on exercise and referral to the hospital gymnasium (if desired), including a visit to, and tour of, the gym and introduction to the gym instructor. They were seen weekly or fortnightly for three sessions of motivational interviewing. Following this, patients were monitored monthly for weighing.

Results

A total of 44 patients (28 female, 16 male) received the intervention. Mean (s.e.) baseline weight was 96.1 (3.1) kg; mean (s.e.) baseline BMI was 33.1 (0.84). Mean weight change for the whole group was -3.1 kg. All patients were offered a year of treatment, but some dropped out prematurely and others requested a longer follow-up. Mean (s.e.) time from baseline to end-point was 355.7 (32.5) days.

To correct for this variation in time, and for the differing number of time points measured among individuals, data were converted into long clusters, imported from SPSS-10 into STATA-7 and regression analysis with robust standard errors performed. We found no significant change in weight overall. Furthermore, we failed to find any predictors of response.

Patients were on a variety of antipsychotic treatment, and some were also treated with mood stabilisers and antidepressants (Table 1). The majority were receiving clozapine or olanzapine. No relationship was found between the primary antipsychotic and weight change, nor did antidepressants or mood stabilisers affect outcome.

Table 1. Medication at baseline and ethnicity

| Medication | Caucasian | African/Caribbean | Asian/Mixed | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clozapine | 6 | 5 | 2 | 13 |

| Olanzapine | 5 | 11 | 1 | 17 |

| Risperidone/amisulpride | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Quetiapine | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Conventional | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Mood stabiliser | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| No | 13 | 16 | 3 | 32 |

| Antidepressant | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| No | 13 | 18 | 1 | 32 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to report the effects of a psychosocial intervention designed specifically to treat overweight people on psychotropic medications for serious mental illness. Overall weight loss was small, but the majority (72.7%) lost weight. This relative failure to lose weight must be set in the context of the study in which people are referred following rapid weight gain on antipsychotic medication.

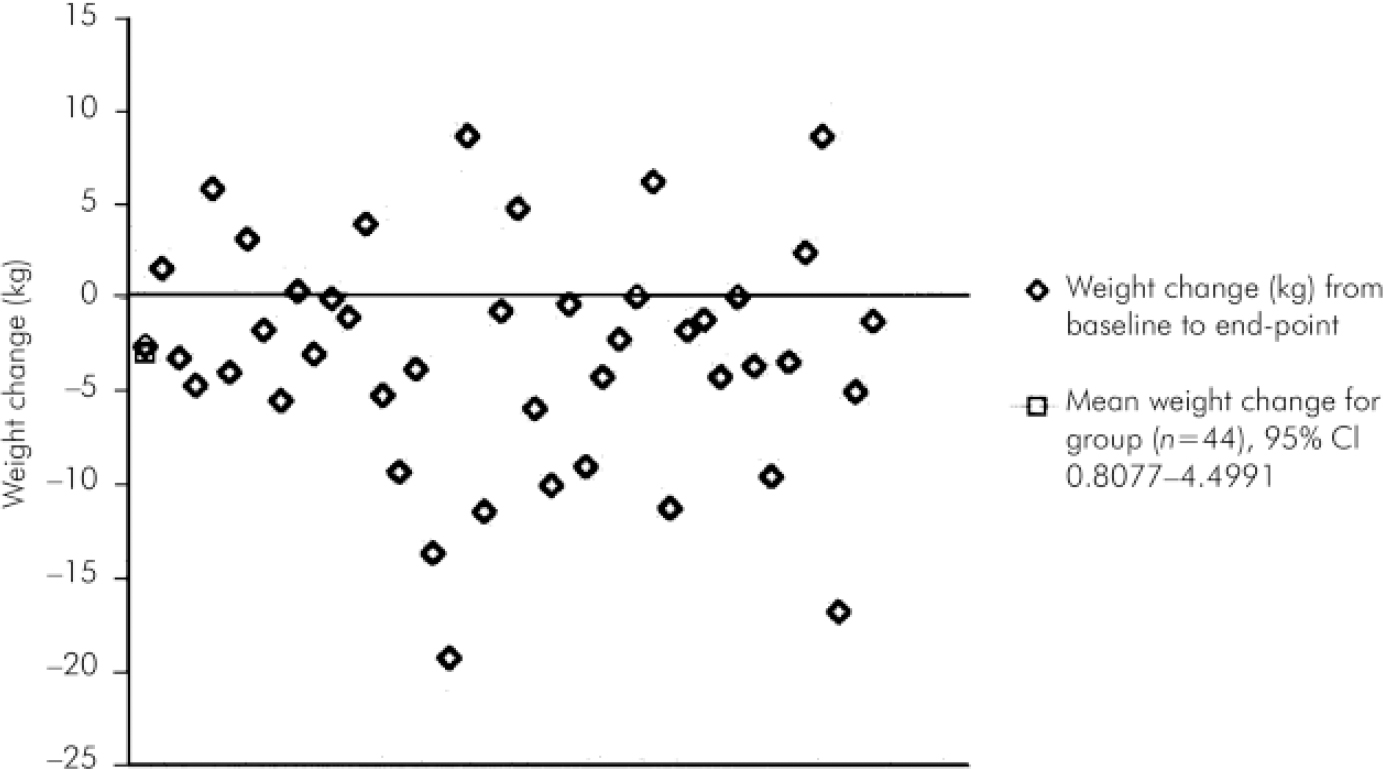

However, there was a wide variation in response to treatment (Fig. 1). Modest lifestyle changes and small weight losses (around 3 kg) prevented 58% of a population without psychoses (n=550) with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) developing diabetes over a 5-year period (Reference Tuomilehto, Lindstrom and ErikssonTuomilehto et al, 2001). The mean weight loss for this group was 3.1kg. Though not statistically significant, such weight losses could have had some benefit by holding off incipient diabetes or IGT.

Fig. 1. Individual weight change (kg) from baseline to end-point in the study plotted against the y-axis (n=44). The points are distributed around zero (no weight change), and there is a wide variability of response. There were no clear demographic or clinical determinants of response.

Methodological considerations

This study is a naturalistic audit of a standardised weight loss programme. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) would provide more information on the efficacy of this approach in comparison with no treatment. However, the current report is an essential step for designing a meaningful RCT. The data show no significant determinant of response, implying that comparator groups could be mixed in terms of age, race and gender. The size of the overall effect also suggests that it might be ethical to randomise patients to a study in which there is a nontreatment/waiting list arm, though this might limit recruitment to the RCT. The variation in length of followup time was a potential limitation in performing the statistical analysis. Using STATA-7, it was possible to convert the data into long clusters and control for the differences in follow-up time by performing regression with robust standard errors. An analysis using the random effects model was also performed in STATA-7 and yielded the same results. The length of time patients were monitored had no effect on weight change. This bears out earlier reports that continuous contact with a therapist does not greatly improve the effect of weight loss intervention (Reference Leibbrand and FichterLeibbrand & Fichter, 2002) in mainstream populations.

Baseline weights before the start of antipsychotic treatment were unobtainable. Estimates of how much weight had actually been gained since the inception of antipsychotic treatment are unreliable. It is difficult to estimate how much weight these patients might have gained without intervention. Allison et al (Reference Allison, Mentore and Heo1999) showed weight gains of 5.5 kg on clozapine and 4.5 kg on olanzapine after 10 weeks’ treatment; the patients in the study reported here were generally stabilised on their medication for longer periods of time. Patients who remained stable, or who gained weight, might have gained more weight without the intervention.

Previous findings

Little data are available on managing antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Pharmacological approaches are not without adverse side-effects and might complicate adherence to antipsychotic medication. Pharmacological interventions are not recommended as suitable for the majority of patients (Reference Werneke, Taylor and SandersWerneke et al, 2002). A systematic search of Medline and PubMed revealed several instances of non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain in people with severe mental illness (Reference Ball, Coons and BuchananBall et al 2001; Reference Umbricht, Flury and BridlerUmbricht et al, 2001; Reference Littrell, Hilligoss and KirschnerLittrell et al, 2003). Littrell et al randomised 70 patients treated with olanzapine to receive either psychoeducation or no intervention. Weight changes between the two groups were statistically significant; mean weight loss for the treatment group was 0.27 kg and mean weight gain for the non-treatment group was 4.35 kg. Umbricht et al (Reference Umbricht, Flury and Bridler2001) described weight losses of 0-21 kg in six patients after 7-10 biweekly sessions of individual/group cognitive-behavioural therapy. Ball et al (Reference Ball, Coons and Buchanan2001) described a cohort of 11 patients (seven males, four females) with olanzapine-related weight gain who attended mainstream ‘Weight Watchers’ meetings and were offered supervised exercise sessions. Overall weight loss was not significant. This sample is larger than that of Umbricht et al and Ball et al, and the mean baseline BMI (33.1) greater than in the Umbricht (29.6) and the Ball samples (31.9). The present data extend earlier research on response to psychosocial weight management interventions.

At present we have no information that can explain the process of change. The patients who lost weight adhered to the prescribed diet, and exercised. Patients who gained weight or remained stable claimed to have followed the diet and exercise regimen also. We are planning a qualitative evaluation of the service using the Focus Group interview technique to uncover the elements of the programme that were helpful to some patients, and inform future service planning and delivery.

Conclusions

The available literature suggests that weight loss programmes, whether psychosocial or pharmacological in the context of antipsychotic medication, do not produce effective, long-term results (Reference Devlin, Yanovski and WilsonDevlin et al, 2000). A focus on prevention, however, could be of benefit. A simple programme to promote healthy eating and lifestyle changes could be incorporated into psychiatric care packages as soon as antipsychotic medication is prescribed.

Further research will investigate biological determinants of antipsychotic-induced weight gain (in particular pharmacogenetic and hormonal influences), identify high-risk groups and follow up the present cohort to determine longevity of response over time.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with unrestricted charitable grants from AstraZeneca, Novartis and Janssen-Cilag. L.S.P. is supported by a UK Medical Research Council Senior Clinical Research Fellowship (G116/101). R.I.O. and L.S.P. have received research grants, consultancy and lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Novartis and Eli Lilly.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.