The first national clinical guideline for the National Health Service (NHS) was produced by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) for the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and launched in December 2002. That the first guideline to emerge was a guideline in mental health was important. Furthermore, that the guideline was about the treatment of the most severe form of mental illness, schizophrenia, has drawn a great deal of attention to the plight of people with mental health problems, both within NICE, its Citizens Council and Partners Council, and in the medical press (Reference Battacharya and GoughBattacharya & Gough, 2002; Reference MayorMayor, 2002; Reference HargreavesHargreaves, 2003).

We are aware, however, that many mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, are not fully cognisant of the policy background, the role of the NCCMH, the aims and possible functions of NICE guidelines, or their methods of production.

This is, therefore, the first in a series of articles about NICE guidelines in mental health. In this article, we introduce the NCCMH in its national context, outline its work programme, and describe the various types and possible uses of guidelines and related products currently being generated for NICE. The second article will describe the NICE process of guideline production with examples, and the third will focus specifically on the schizophrenia guideline, its relationship to other related national initiatives and the experience of generating the first national clinical guideline in what has been described as the world's most ambitious national programme of guideline production.

The background

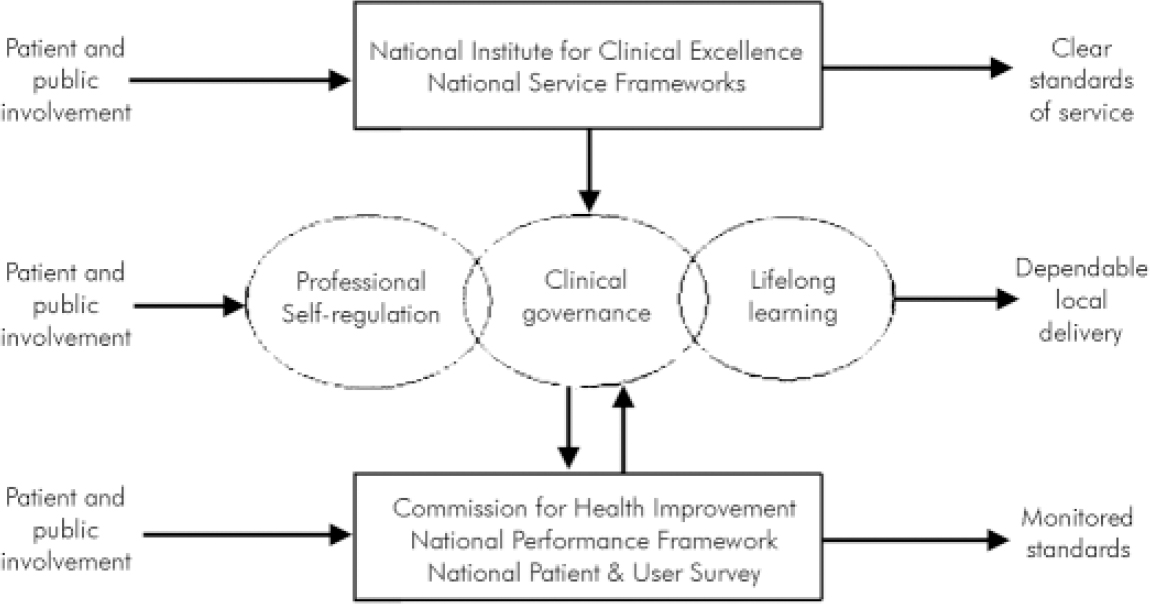

As part of an explicit modernisation programme aimed across the range of public services, the new Labour Government introduced the New NHS. It had new organisations and structures, aimed at continuously improving the quality of treatment and care provided throughout the NHS and reducing inappropriate variation in clinical practice (Department of Health, 1997, 1998). The ‘big idea’ at the heart of the New NHS was to create a system, derived from corporate governance and clinical audit, which would set national standards to be implemented locally and monitored nationally. National standards (and the principles informing them) for service configuration were set through the National Service Frameworks, and national standards for clinical practice would be developed and disseminated by NICE (Reference RawlinsRawlins, 1999).

Local delivery of health care would be made more robust and dependable through the development of local quality improvement systems and mechanisms specifically aimed at incorporating and implementing national standards. This would be achieved under the generic umbrella of clinical governance, through which NHS trusts were to undergo substantial internal reorganisation from the trust board (Reference Kendall and PalmerKendall & Palmer, 2004) through to the individuals and teams delivering care, with the creation of new roles and responsibilities (Reference Kendall, Kendall, James, Kendall and WorrallKendall & Kendall, 2004).

To monitor local implementation, the Commission for Health Improvement (CHI) was established, with the responsibility to regularly review the local development of structures and processes to improve the quality of care, and to monitor the local implementation of national standards and NICE guidance. The now well-known diagram for the structure of the New NHS is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Setting, delivering and monitoring standards (from Littlejohns, 2003).

Originally conceived as a facilitative system for quality improvement, the status and role of the various organisations and structures have changed in the light of changing political and public attitudes, often in response to high-profile untoward events within the NHS. For example, CHI will soon become the Commission for Healthcare, Audit and Inspection (CHAI), having taken over the national audit function originally to be developed by NICE, and it will now operate as an inspectorate.

NICE

In this context, the ongoing responsibility for generating the national guidance for improving the quality of clinical practice, and reducing variation therein, lies with NICE, who execute this duty in a number of different ways. NICE commission and oversee the National Confidential Enquiries, such as the National Confidential Enquiry into Suicides and Homicides in People with Mental Illness (Department of Health, 2001). They also develop and publish referral advice, and have recently launched an interventional procedures assessment programme. However, its two main programmes are more directly relevant here.

First, NICE have a very active Health Technology Appraisal programme, in which individual health technologies, such as cognitive enhancers for dementia (National Institute for clinical Excellence, 2001) or atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002) are subject to a detailed evaluation of the evidence base for their use in the NHS. This is the first time that treatments provided by the NHS have been exposed to such a rigorous and robust appraisal of their clinical and cost effectiveness, independent of the pharmaceutical industry. The second method for generating standards is through the production of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the integrated treatment of a particular condition or disorder, such as diabetes or schizophrenia.

When NICE was established as a Special Health Authority in 1999, it took over and further developed a wide range of national guidelines and audit projects, supporting some 26 academic, professional and clinical units. Following a review of this work in 2000, NICE took the decision to concentrate expertise and increase guideline production capacity by establishing just six guideline development units. This also meant that NICE could commission and oversee the introduction and use of highly rigorous methods of guideline production. The guideline units NICE agreed to fund were all collaborations between different professional, academic, and sometimes service user organisations. Units were encouraged to work together and to meet together for sharing experience, working collaboratively and undergoing training. These units became known as the National Collaborating Centres (NCCs).

The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health

Six NCCs were established on 1 April 2001, each with responsibility to generate evidence-based guidelines for a particular, but not exclusive, area of health care, and a seventh devoted to cancer has been established more recently. The seven NCCs cover:

-

(1) primary care;

-

(2) women and children's health;

-

(3) nursing and supportive care;

-

(4) chronic conditions;

-

(5) acute care;

-

(6) mental health;

-

(7) cancer.

NCCs are led by one or more professional or academic organisation(s), usually a Royal College, in collaboration with other related health organisations to promote interdisciplinarity. The NCCMH is a contractual partnership between the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the British Psychological Society and is hosted by the respective research and effectiveness units for each partner: the College Research Unit (CRU) and the Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation. To ensure a genuine partnership, the NCCMH has a management board, made up of two co-Directors and senior representatives from both the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the BPS, and an advisory reference group made up of representatives of national professional and service user organisations and two academic centres, including:

Professional organisations

-

Royal College of Psychiatrists

-

British Psychological Society

-

Royal College of Nursing

-

Social Care Institute for Excellence

-

College of Occupational Therapists, now replaced by the Clinical Effectiveness Forum for the Allied Health Professions

-

Royal College of General Practitioners

-

Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Service user and carer organisations

-

Rethink Severe Mental Illness (formerly the National Schizophrenia Fellowship)

-

Manic Depression Fellowship

-

MIND

Academic organisations

-

Centre for Evidence-Based Mental Health

-

Institute of Psychiatry

The NCCMH has just under 20 full-time members of staff including systematic reviewers, project managers, an information scientist, health economists, research assistants, administrators, an editor and the co-Directors, with the capacity to develop six guidelines concurrently.

Guidelines

The selection of the disorders for which NICE guidelines are commissioned is a political matter decided by ministers and the Department of Health, but a proposal is currently under scrutiny to develop a web-based system to promote topic nomination by patients, patient and professional groups, the wider NHS and manufacturers of health care products, and their review by a topic advisory committee (www.nice.org.uk/Docref.asp?d=63378). Once topics have been determined, they are offered to the most appropriate NCC, subject to capacity. Guidelines completed, underway or planned for the NCCMH (with completion or start dates in parentheses) are:

-

(1) schizophrenia (December 2002);

-

(2) eating disorders (January 2004);

-

(3) depression and resistant depression (early 2004);

-

(4) self harm (mid 2004);

-

(5) depression in childhood (late 2004);

-

(6) post-traumatic stress disorder (early 2005);

-

(7) obsessive-compulsive disorder (mid to late 2005);

-

(8) bipolar affective disorder (start 2004);

-

(9) dementia (start 2004).

Developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in mental health involves a detailed evaluation of the specific role of pharmacological, psychological, service-level and sometimes self-help interventions in the treatment of a specific disorder. Precisely what a guideline will address is negotiated in advance through the development of a ‘scope’, which sets out the people, contexts, services and treatments that will, and will not, be covered by the guideline. The scope is developed between registered stakeholders (such as the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Rethink and drug companies), the Department of Health and the Welsh Assembly, NICE and the commissioned NCC. Once the scope and a work-plan have been agreed, they are put onto the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk) and a guideline development group assembled, including professionals, experts, service users and carers, to begin the usually 2-year process of guideline production.

Given the time, people and resources involved, and the substantial body of evidence collected, quality assured, analysed, critically appraised and synthesised, these guidelines have a number of potential uses, including:

-

providing up-to-date evidence-based recommendations for the management of conditions and disorders by healthcare professionals

-

assisting service users and carers in making informed decisions about their treatment and care

-

improving communication between health care professionals, service users and carers

-

the education and training of health care professionals

-

to set standards to assess the practice of health care professionals

-

to guide investment by commissioners

-

helping to identify priority areas for further research.

Guideline products

Anticipating their broad potential, each NICE guideline has a number of different inter-related forms that reflect these different uses. There is a ‘ full guideline’, a ‘NICE guideline’, a service user/public version, one or more clinical practice algorithms/care pathways and an audit tool. For the schizophrenia guideline, the NCCMH has also produced a training website.

The full guideline

The full guideline gives the background for the disorder under consideration and the types of treatments the NHS currently provides; it describes the methods in detail and contains all the evidence, statements, recommendations, references, analyses, clinical algorithms, care pathways and an audit tool. All the recommendations made in each section of the full guideline are collected into one chapter: the Summary of Recommendations. This is extracted from the full guideline to produce the ‘NICE guideline’. The full guideline is a detailed and transparent archive from which future revisions of the guideline will begin. All other guideline products are derived from the full guideline. The final version of this is owned by the NCCMH, and published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the British Psychological Society. It is aimed at professionals, academics or other guideline producers. For the schizophrenia guideline, the full version is over 800 pages in length.

The NICE guideline

This contains all the recommendations collected in the Summary of Recommendations chapter of the full guideline, the audit tool, the algorithms and care pathway(s), and has the service user/public version as an appendix. The NICE guideline is owned and published by NICE, and disseminated throughout the NHS in England and Wales. The target audience is the professional health worker.

Understanding NICE guidance - information for service users, their advocates and carers, and the public

This version is a plain English version that parallels the NICE guideline, and explains step-by-step what the service user (and their carers) can expect in terms of the services available, the treatments offered, and the approach that staff should take with them (written as if the NICE guideline had been fully implemented). This version is owned and published by NICE and disseminated throughout the NHS in England and Wales. The audit tool in the schizophrenia guideline includes as a standard that all people with schizophrenia and their carers should be given a copy of this version of the guideline.

Clinical practice algorithms and care pathways

These are a simplified, diagrammatic representation of different parts of a guideline. These are useful both as a quick guide to the guideline, and as a means of getting a broad overview of the whole guideline, all at once. These can be found in the full guideline and are published separately and disseminated with the NICE guideline.

Training web-site

For the schizophrenia guideline, the NCCMH have developed a website for training professionals how to use the NICE schizophrenia guideline (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/cru/sts/index.htm). This training site is freely accessible and interactive, with short tests throughout the training programme. The site is designed around the clinical practice algorithms and care pathway, and takes the viewer through each algorithm with the relevant ‘pop-up’ evidence statements and recommendations at each step in the algorithm.

Methods

NICE guidelines are developed using internationally agreed methods (AGREE: www.agreecollaboration.org), methods updated regularly through research and consultation. The next article will explain how we go about producing NICE guidelines with examples.

Materials

The training web-site is now available as a CD-Rom (funded by the National Institute for Mental Health in England), from the NHS Response Line 0870 1555 455 (reference number NO203). The NICE schizophrenia guideline and the service user version ‘Understanding the NICE guideline’ are available on the NICE website. Paper versions can be ordered from the NHS Response Line on 0870 1555 455 (quoting number NO176 and NO177). The full schizophrenia guideline can be purchased from Gaskell.

Declaration of interest

The NCCMH is funded by NICE. The National Institute for Mental Health in England funded the production of the CD-Rom version of the training web-site for schizophrenia. T.K. and S.P. are in receipt of grants from the DoH.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.