Clinical audit is regarded as an essential component of clinical governance, which is expected to result in improvements in patient care and to assure trusts that their services meet national quality standards.

Several studies have examined the views of health care professionals on clinical audit. An overview by Johnston et al (Reference Johnston, Crombie and Davies2000) noted that perceived benefits include improved communication between professional groups and increased professional satisfaction and knowledge, whereas potential disadvantages include diminished clinical ownership, fear of litigation and professional isolation. Although clinical audit should form an essential part of junior doctors’ training, little has been published on the views of the junior doctors who take part in it. A postal survey of junior doctors showed that although 74% of their sample had been involved in audit, a large proportion of projects did not conform to good practice and only 12% carried out a further audit (Reference Greenwood, Lindsay and BatinGreenwood et al, 1997). These findings were echoed in a more recent study which found that often activities that were labelled as ‘audit’ were methodologically poor and that this could produce a negative attitude among junior doctors towards the process (Reference Nettleton and IrelandNettleton & Ireland, 2000). This paper describes an audit completed by a specialist registrar in order to demonstrate the kind of project that can successfully be undertaken by trainees.

Method

Encouraged to take on an audit as part of her training, one of the authors (I.C.) decided to examine and attempt to improve the recording of information in psychiatric discharge summaries in the department in which she was working. She chose this subject for a number of reasons.

The discharge summary is potentially a valuable document for the psychiatric team, providing detailed information concerning a patient’s hospital admission, previous clinical history and potential risk factors for the patient and those involved in his or her care. However, I.C. noted that not infrequently important information on drug, alcohol and forensic histories was missing. The discharge summary should also provide details of a patient’s admission to the general practitioner, but several studies have identified deficiencies in their quality in this respect. These mainly concern timeliness, accuracy and length (Reference Macauley, Cooper and EngesetMacauley et al, 1996; Reference Wilson, Ruscoe and ChapmanWilson et al, 2001; Reference Foster, Paterson and FairfieldFoster et al, 2002). In a survey of the views of general practitioners on psychiatric discharge summaries (Reference Dunn and BurtonDunn & Burton, 1999), their top five headings in terms of importance were:

-

1. admission and discharge dates

-

2. diagnosis

-

3. medication on discharge

-

4. community keyworker

-

5. date of follow-up.

Another survey of the views of hospital physicians, junior doctors and general practitioners ranked ‘medication on discharge’, ‘ significant results of investigations’ (both positive and negative) and ‘follow-up arrangements’ particularly highly (Reference Solomon, Maxwell and HopkinsSolomon et al, 1995). In addition to the above items, the inclusion of an ICD-10 diagnosis on the discharge summary was thought to be important because it is used by coding departments for statistical information about the service. The following ten headings were therefore selected for the study: diagnosis; ICD-10 compatible diagnosis; drug history; alcohol history; smoking history; forensic history; results of blood tests; physical examination; medication on discharge; and follow-up arrangements.

The audit cycle

The first part of the audit took place between October and December 1999. Fifty-one consecutively produced discharge summaries for patients aged 18-65 years discharged from acute adult psychiatric wards were examined (by I.C.). Part 1 summaries were included only if they were incorporated as part of the final discharge summary (Part 1 summaries provide an initial account of the history and mental state examination and are produced shortly after admission). The patients were under the care of eight consultants and the summaries had been written by nine junior doctors. Information under each heading was scored as being present or absent, or a note was made if it was recorded as ‘See previous discharge summary’. No attempt was made to ascertain the accuracy of the information recorded. A standard of 100% was set for the recording of all the items.

Results

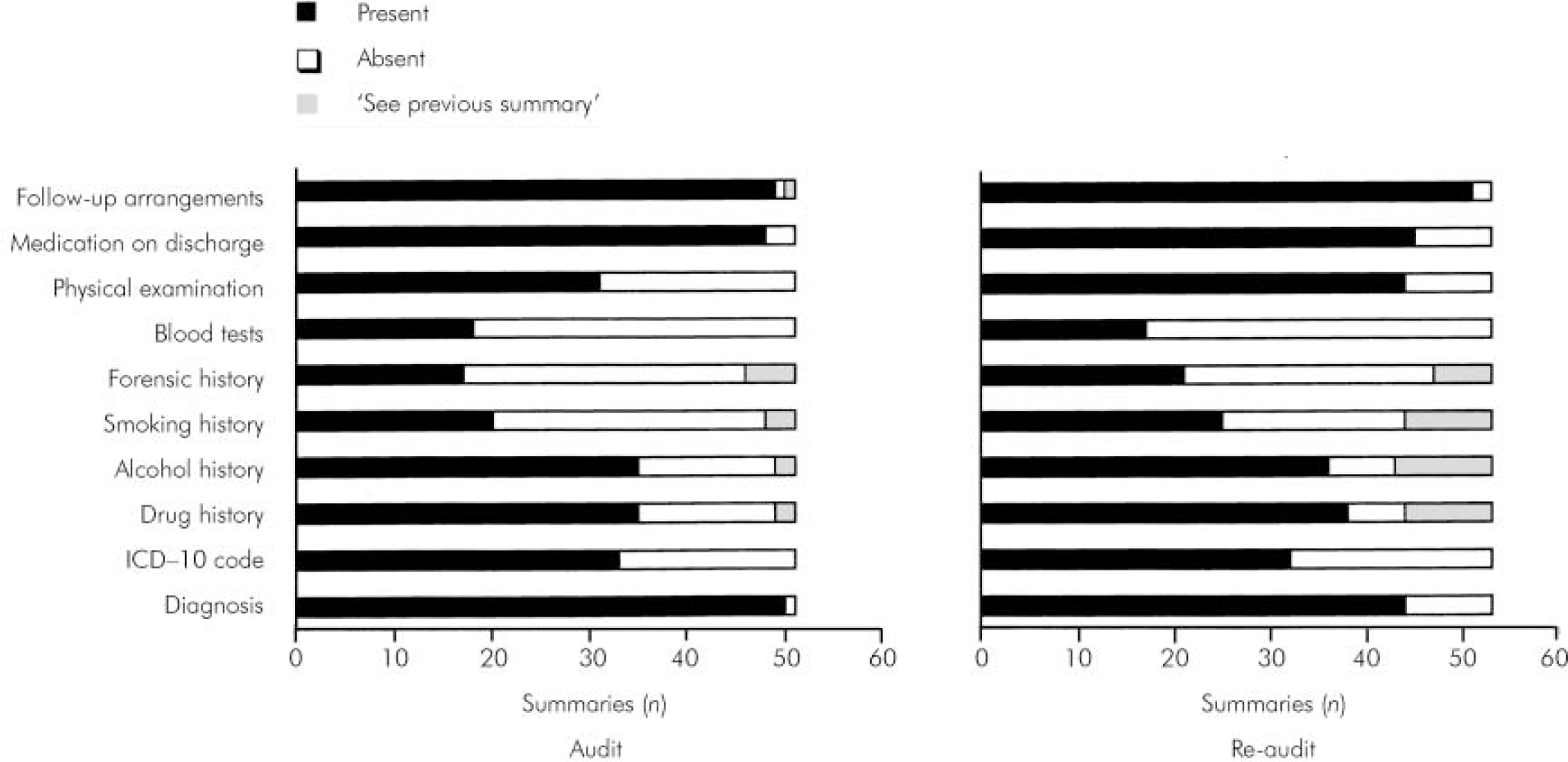

The results of the first audit were presented to the trainees and consultants in February 2000 (Fig. 1). It was agreed that current practice fell short of a desirable standard, particularly in the areas of blood test results, forensic history and smoking history. A number of recommendations were made. These included:

-

• Trainees should receive specific tuition on writing discharge summaries.

-

• A number of discharge summaries should be checked randomly by consultants, with feedback to trainees.

-

• The ICD-10 diagnosis should be discussed at ward rounds.

-

• Copies of ICD-10 codebooks should be readily available on each ward.

-

• A written report of the initial findings and recommendations should be circulated to all interested parties.

-

• The audit should be repeated in due course.

Fig. 1. Results of audit and re-audit of information in discharge summaries.

The audit was repeated between May and July 2000. Fifty-three summaries were examined on this occasion. These summaries were produced by a new cohort of junior doctors, but these were the ones who had received the results of the original audit early in their posts and who were subject to the subsequent recommendations. The audit was carried out towards the end of the senior house officers’ 6-month posting to allow sufficient time for changes in practice to be realised.

The results of the two audits are shown in Figure 1. There was no statistically significant difference between the first and second audits for any item. Indeed, the patterns of information recording were very similar at both times, despite the fact that the results reflected the performance of two different groups of junior doctors.

Discussion

In this audit project we were unable to produce any notable improvement in the standard of information recording in psychiatric discharge summaries. On reflection, there may be a number of reasons why this study was unable to show a change in practice following audit and feedback:

-

• Discharge summaries might not have been perceived as an area of clinical priority.

-

• Because the study involved a number of different teams, individual doctors might not have felt a sense of ownership of the project.

-

• Prior to the second data collection we were unable to ascertain if all the recommended interventions had been implemented.

-

• The method of feedback we used might not have been the most effective.

The similarity in the patterns of information recording between the two groups was the most interesting finding in this study, and may point to another explanation for the overall finding of no improvement - that is, that junior doctors may use their predecessors’ work as a template when producing discharge summaries and therefore repeat the same mistakes. If this is the case, there remains a further opportunity for intervention and change.

Although the results of this project were in some ways disappointing, review of previously published work showed that they were not altogether unsurprising, Cochrane reviews concluded that although audit and feedback can be effective in improving the performance of health care providers, the effects are generally small to moderate (Reference Thomson O'BRIEN, Oxman and DavisThomson O’Brien et al, 2000a ), even when complementary measures are also used (Reference Thomson O'BRIEN, Oxman and DavisThomson O’Brien et al, 2000b ).

Although no improvement in practice was achieved from this audit, I.C. was able to reflect on the positive aspects of the experience, which are likely to be relevant to other trainees. First, the project was undertaken in her first specialist registrar post, which allowed plenty of time for the audit and reaudit to be completed and written up during her training. Second, the project was her own idea and was felt to be relevant and clinically important, which helped with motivation to complete it. Third, data collection was kept simple. The relevant information was easy to access, a ‘yes/no’ answer method was used and no personal or clinical data were recorded. Finally, the timing of the feedback was planned to allow enough time for change before reaudit.

It is not easy to modify the clinical practice of health care professionals, and perhaps clinical audit does not hold all the answers. However, through carrying out a well-designed and planned audit, the trainee can gain a valuable insight into a process that is promoted as a major tool for monitoring and effecting change in our clinical practice.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Clinical Audit Department of Tower Hamlets Healthcare National Health Service Trust for their assistance in this project.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.