This study describes the case-loads of 29 assertive outreach teams in 12 trusts in the North East of England. It compares the case mix for these teams with that of community mental health teams (CMHTs) prior to the introduction of assertive outreach.

As a model for the delivery of mental health services in the community, assertive outreach is based on evidence gathered mainly in the USA about assertive community treatment. This has been extensively described, evaluated and reviewed (Reference Bond, McGrew and FeketeBond et al, 1995; Reference Stein and SantosStein & Santos, 1998; Reference Marshall and LockwoodMarshall & Lockwood, 1998). Overall, when compared with ‘standard’ community mental healthcare in the USA, assertive community treatment has been found to reduce hospital use, increase housing stability and promote satisfaction among people with severe mental health problems who have had repeated hospital admissions. Despite equivocal findings as to its effectiveness in the UK (Reference Burns, Fiander and KentBurns et al, 2000; Reference Ford, Barnes and DaviesFord et al, 2001; Reference Weaver, Tyrer and RitchieWeaver et al, 2003), assertive outreach has been adopted nationwide and extensive evaluations undertaken. In the Pan-London Assertive Outreach Study, Wright et al (Reference Wright, Burns and James2003) explored fidelity to the model in London teams, and Billings et al (Reference Billings, Johnson and Bebbington2003) have reported on the differences between the experiences of staff working in assertive outreach compared with CMHTs as part of the same study. Priebe et al (Reference Priebe, Fakhoury and Watts2003) present descriptive data about the people using assertive outreach in the London study but, to date in the UK, the case mix of people on assertive outreach case-loads has not been fully investigated.

The Policy Implementation Guide (Department of Health, 2001) required all mental health services to have implemented assertive outreach by April 2003, and by September 2003 an estimated 236 teams were set up, although some had yet to achieve a full case-load (data are from Adults of Working Age Mental Health Service Mapping Exercises sponsored by the Department of Health (http://www.amhmapping.org.uk)). A crucial factor in the achievement of effective assertive outreach is likely to be the threshold for admission to the service. Overinclusive services may dilute their impact whereas overly selective services may lead to an inequitable use of resources. Who receives (and who does not receive) assertive outreach will have implications for hospital beds and community mental health services in a locality, as they interface directly with the new teams.

The criteria for inclusion in assertive outreach are explicit in the Policy Implementation Guide (Department of Health, 2001). This specifies assertive outreach for adults with severe mental health problems, high use of hospital, difficulty maintaining contact with services and complex or multiple needs that might include:

-

• a history of violence or offending

-

• risk of self-harm or self-neglect

-

• poor response to previous treatment

-

• dual diagnosis

-

• detention under the Mental Health Act1983 in past 2years

-

• unstable accommodation or homelessness.

In this study we investigate the implementation of assertive outreach in one region in relation to the policy guidelines. We do so by presenting details of assertive outreach clients in the north east of England and comparing these with the case-loads of local CMHTs.

Hypothesis

We expected the case mix of assertive outreach teams to differ from those of CMHTs, with people on assertive outreach case-loads being, in general, significantly more severely disabled by mental health problems, more at risk of harm and less manageable in terms of care plans, posing greater risk to other people, and having a more serious history of aggression, self-neglect and self-harm.

Method

A consortium of providers and researchers in the former Northern and Yorkshire Health Region met in October 2000 to explore common needs for research concerning the development of assertive outreach in the region. All trusts were invited to contribute funding to the enterprise and, without exception, those approached did so. The resulting study design included a survey of case-loads using the Matching Resources to Care-2 (MARC-2; Reference Huxley, Reilly and GaterHuxley et al, 2000), Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS; Reference Wing, Beevor and CurtisWing et al, 1998) and Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Reference Endicott, Spitzer and FleissEndicott et al, 1976). The MARC-2 generates an 18-point summary score of severity and risk, called M3, and also contains a number of items that relate directly to service use history and risk, which are directly comparable to the Policy Implementation Guide criteria.

Ethical approval was granted for the study by the multi-site research ethics committee and confirmed by all the local research ethics committees in whose jurisdiction the study was undertaken. Data collection was undertaken between September 2002 and April 2003.

Using the same measures as in this study, Huxley & Brandon conducted a case-load survey in 2000 in County Durham and Darlington, which contains data on 1128 people. Similarly, Brandon collected data on 407 mental health service users in Northumberland in 2002. (Details of both these studies may be obtained from T.B. on request.) These data-sets, like those generated by the present study, were rated by care coordinators. All three data-sets are censuses and therefore effectively comprise the whole population of service users in each area. However, the previous studies differ from the present study in important ways.

-

(a) The data were collected earlier with services at a different stage of development and before assertive outreach teams were introduced.

-

(b) The geographical areas covered include two of the more rural and thinly populated parts of the region, which may affect the way services are delivered.

Bearing in mind these fundamental differences, the previous studies are used here to draw comparisons between ‘typical’ community mental healthcare in the region before the introduction of assertive outreach and the case-loads of these teams set up in subsequent years. In the analysis we treated service users in each trust as being exchangeable with likely new case-loads for that trust, so that the service users for whom we have data can be considered as a random sample of present and future case-load. As such, we may apply standard statistical techniques to explore differences between case-loads. We treated service users in the two CMHT surveys similarly. To explore discrete outcomes we used the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test where possible. As a third method, we use generalised linear modelling to explore patterns for counts in contingency tables. These three methods generally agreed for our analyses. To explore numerical outcomes we use standard analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA. These two methods generally agreed for our analyses.

Results

Ultimately, 12 mental health trusts, with 29 assertive outreach teams, participated in the study. They gathered data concerning 836 users of assertive outreach. In this analysis we compare the characteristics of clients of assertive outreach teams with those of CMHTs in Northumberland (CMHT 1) and Durham and Darlington (CMHT 2). We explored the case-load characteristics in relation to the guideline criteria for inclusion in assertive outreach, but first we describe the sample. Unless otherwise stated, the analyses reported here were performed with 2 degrees of freedom.

There were very many more male clients in the assertive outreach teams, 69% compared with 44% in CMHT 1, and 45% in CMHT 2 (χ2=124.87, P<0.001). Users of assertive outreach were a little younger at the time of the census, having a mean age of 38 years compared with 43 years for the other two studies (F(2, 2321)=45.52, P<0.001). The recorded age at onset of severe mental health problems was lower for assertive outreach users (24 compared with 34 and 33 years for the CMHT case-loads (F(2, 2161)=188.40, P<0.001)).

Of assertive outreach users, 10% belonged to minority ethnic groups compared with 3% of the CMHT samples; this reflects the different geographical locations of the three studies. In keeping with the younger mean age, significantly more assertive outreach users were single (never married) (70% compared with 33% and 37% in previous studies (χ2=249.79, P<0.001)). Table 1 profiles the accommodation arrangements of each group. It indicates that more assertive outreach users were homeless and more were living in supported settings, including hospital, at the time of the study, whereas two-thirds of CMHT clients lived in their own homes without professional support (see Table 1).

Table 1. Types of accommodation for assertive outreach users compared with community mental health team (CMHT) users

| Assertive outreach | CMHT 1 (%) | CMHT 2 (%) | χ 2 1 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homeless | 4.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 11.41 | 0.003 |

| Own home without professional support | 28.3 | 66.3 | 67.0 | 314.23 | < 0.001 |

| Own home with professional support | 36.1 | 20.9 | 17.5 | 90.93 | < 0.001 |

| Bed and breakfast | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.058 | 0.971 |

| Group home | 2.6 | 0 | 1.0 | 15.03 | 0.001 |

| Other sheltered housing | 4.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 14.20 | 0.001 |

| Residential care (without 24-h support) | 2.0 | 0 | 0.2 | 22.83 | < 0.001 |

| Residential care (24-h support) | 5.0 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 24.89 | < 0.001 |

| Nursing home (24-h care) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.639 | 0.727 |

| Hospital | 10.0 | 4.4 | 7.6 | 11.12 | 0.004 |

| Other | 6.0 | 0.5 | 0 | 84.36 | < 0.001 |

Severe mental health problems

We expected people receiving assertive outreach services to have more severe mental health problems than the ‘average’ for community mental health services. Analysis of this data-set bears this out, with assertive outreach users being rated by their key workers as more severely impaired. This is reflected in a marked difference on all three indicators (see Table 2).

Table 2. Summary scores of severity of mental health problems by study

| Assertive outreach (n=836) | CMHT 1 (n=400) | CMHT 2 (n=1128) | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoNOS | F=227.8 | |||

| mean | 15.49 | 11.08 | 8.57 | (2, 2249) |

| (s.d.) | (7.85) | (7.03) | (6.16) | P < 0.001 |

| HoNOS | ||||

| range | 0-42 | 0-36 | 0-33 | |

| (n in sample) | (795) | (378) | (1079) | |

| GAS | F=45.6 | |||

| mean | 50.78 | 57.46 | 57.74 | (2, 2338) |

| (s.d.) | (17.29) | (16.83) | (16.14) | P < 0.001 |

| GAS | ||||

| range | 0-100 | 0-95 | 0-100 | |

| (n in sample) | (826) | (400) | (1115) | |

| M3 | F=524.9 | |||

| mean | 7.72 | 3.23 | 2.90 | (2, 1932) |

| (s.d.) | (3.28) | (3.37) | (2.77) | P < 0.001 |

| M3 | ||||

| range | 0-18 | 0-17 | 0-17 | |

| (n in sample) | (678) | (339) | (918) |

The diagnostic profiles obtained by our method are not adequate for detailed analysis, but a rough guide is that 95% of assertive outreach users were deemed by their keyworker to have a ‘psychotic illness’ compared with 31% for CMHT 1 and 45% for CMHT 2 samples overall (χ2=653.65, P<0.001).

High use of hospital

Of assertive outreach service users, 56% had at some time been in hospital for more than 6 months. In the CMHT 1 study this applied to only 19% and in the CMHT 2 survey to 18%, even though, as reported above, the user group was significantly older (χ2=338.09, P<0.001).

The number of hospital admissions in the past 2 years was coded as never, one or two and three or more. Approximately half the assertive outreach users (53%) had one or two admissions compared with 19% and 25% of the CMHT case-loads. A further 30% of assertive outreach users had three or more admissions in the previous 2 years compared with 7% and 3% of the CMHT user groups (χ2=625.99, d.f.=4, P<0.001).

Difficulty maintaining contact with services

Three variables from the MARC-2 reflect difficulty maintaining contact with services: cooperation with help offered, adherence to medication and keeping appointments. In all three respects, assertive outreach users were significantly more likely to be rated ‘poor’ for cooperation. In relation to help offered, 17% were rated ‘poor’ compared with 9% and 6% (χ2=69.86, P<0.001). In relation to taking medication, 22% compared with 7% and 4% were rated ‘poor’ (χ2=167.08, P<0.001). As for keeping appointments, 20% compared with 10% and 5% were rated ‘poor’ (χ2=100.56, P<0.001).

Violence

According to keyworkers, a higher proportion of assertive outreach users were currently aggressive towards their family and towards other people compared with the CMHT users (see Table 3). They were three times more likely to display aggression towards family members, and more than twice as likely to show aggression towards others.

Table 3. Aggression and self-harm in assertive outreach and CMHT users

| Assertive outreach (%) | CMHT 1 (%) | CMHT 2 (%) | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present behaviour | |||||

| Aggression towards family | 11.5 | 7.6 | 3.2 | 50.29 | <0.001 |

| Aggression towards others | 16.3 | 10.3 | 6.3 | 50.5 | <0.001 |

| Suicide attempts | 6.5 | 7.9 | 3.9 | 11.2 | 0.004 |

| Self-neglect | 10.5 | 7.9 | 3.8 | 35.1 | <0.001 |

| Self-harm | 10.2 | 10.6 | NA | 0.11 | NS |

| Past behaviour | |||||

| Aggression towards family | 51.2 | 17.4 | 17.8 | 289.9 | <0.001 |

| Aggression towards others | 64.6 | 23.1 | 21.1 | 429.3 | <0.001 |

| Suicide attempts | 46.2 | 31.5 | 28.1 | 70.8 | <0.001 |

| Self-neglect | 41.9 | 14.7 | 12.5 | 248.2 | <0.001 |

| Self-harm | 41.4 | 26.0 | NA | 27.11 | <0.001 |

Risk of self-harm or self-neglect

There was a much higher prevalence of past suicide attempts, other forms of self-harm, and self-neglect by assertive outreach users. However, current levels of selfharm did not differ from those of the comparator groups (see Table 3). We re-analysed the data by combining the two CMHT studies into one group and comparing this with the assertive outreach group. Except in one regard, the results were essentially identical. That is, strong differences (P<0.001) between the assertive outreach group and the CMHT group, and no significant difference in rates of present self-harm. The exception is that there was no significant difference in rates of perceived current suicide risk between the two groups, so that the finding in Table 3 is more one of general heterogeneity between the three groups.

Dual diagnosis

Of assertive outreach case-loads, 28% of people had problematic drug use compared with 15% in CMHT 1 and 3% in CMHT 2 samples (χ2=251.4, P<0.001). Of assertive outreach service users, 31% were judged by their keyworkers to have problems with alcohol use compared with 15% of people on the CMHT 1 case-load and 3% on the CMHT 2 case-load (χ2=302.3, P<0.001).

Detention under the Mental Health Act 1983 in past 2 years

Of the individuals in the current sample, 86% had a compulsory admission at some point in their lives compared with 24% in CMHT 1 and 26% in CMHT 2 (χ2=786.78, P<0.001). Among assertive outreach users, 17% had been admitted under Section 3 compared with 4% and 1% (χ2=188.9, P<0.001), and 6% had been admitted under Section 2 compared with 1% and 0.5% of CMHT users (χ2=68.1, P<0.001).

Unstable accommodation or homelessness

As noted in Table 1, 4.1% of the assertive outreach case-load was homeless at the time of the study. Thirty-six per cent had been homeless at some time compared with 8% of CMHT 1 and 8% of CMHT 2 (χ2=277.77, P<0.001). In terms of accommodation problems in general, 17% of assertive outreach clients were judged to have severe difficulties compared with 5% of CMHT 1 and 4% of CMHT 2 case-loads (χ2=119.32, P<0.001).

Evidence of complex or multiple needs

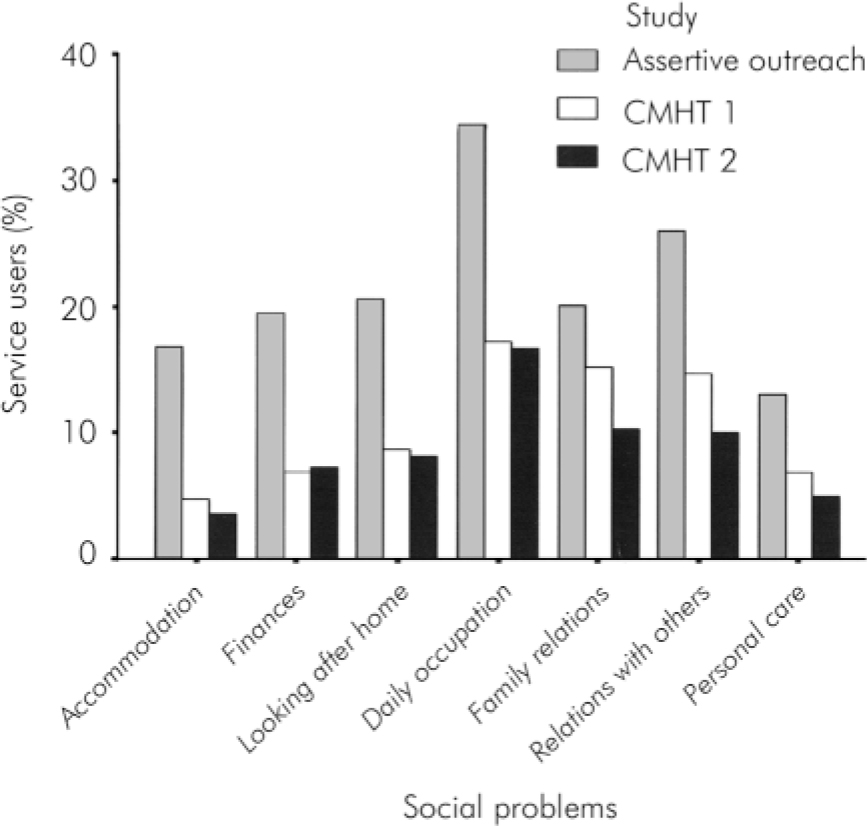

The MARC-2 generates a summary score, called M3, which includes 18 variables. Several of these have already been reported: compulsory admissions, psychosis, cooperation, dual diagnosis, self-harm and aggression. Eight other variables relate to problems people might have in coping with everyday life (personal care, relationships with others, relationships with family, employment, looking after the home, finances, housing and risk of institutionalisation, which includes risk of admission to hospital). Figure 1 compares the percentage of individuals in each study who were deemed by their keyworkers to experience severe problems in each of these domains.

Fig. 1. Severe social problems experienced by service users of assertive outreach and community mental health teams (CMHTs).

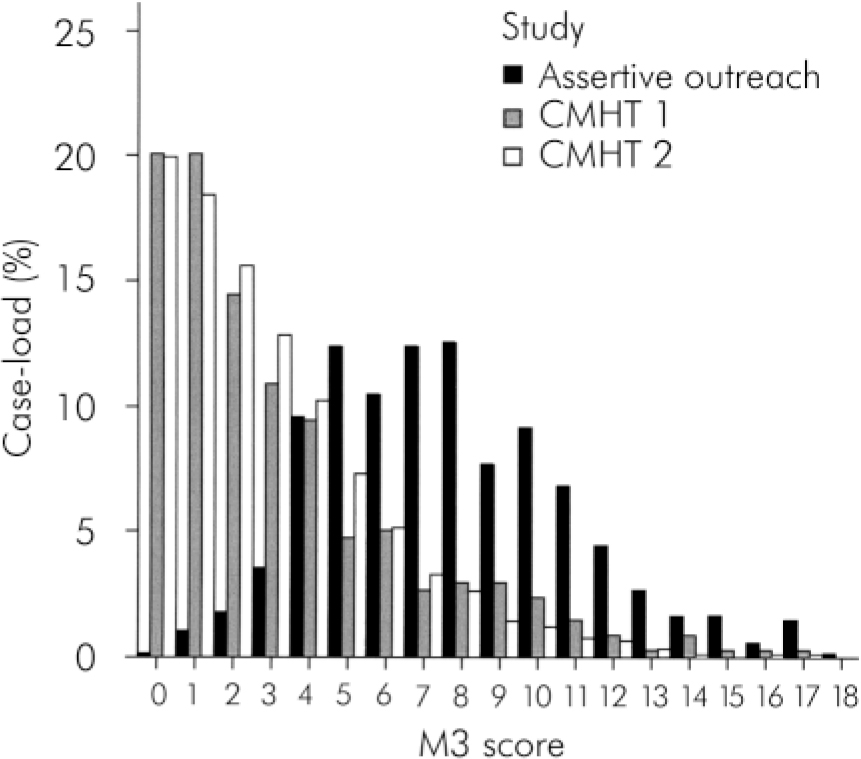

Fig. 2. M3 score distribution for case-loads of all studies.

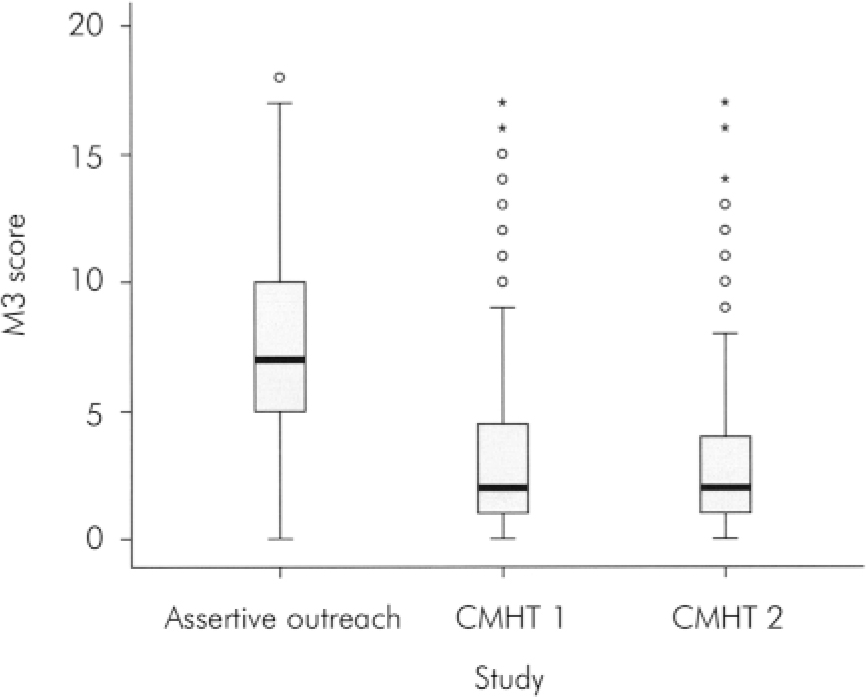

Fig. 3. Overall MARC-2 summary scores (M3) for all studies. Summary plot based on the median, quartiles and extreme values. The box represents the interquartile range which contains the 50% of values. The whiskers are lines that extend from the box to the highest and lowest values, excluding outliers. A line across the box indicates the median (SPSS Help Topics).

Figure 2 shows the respective distributions of the M3 summary score for CMHT and assertive outreach case-loads. This confirms the inference from the evidence presented here that there is a clear difference in case-load profile, with assertive outreach teams serving more severely impaired people.

The box plot (Fig. 3) is a summary of our findings: some M3 severity scores that would be outliers for CMHTs (shown as circles) are within the interquartile range for assertive outreach teams, whereas scores that would be extremes for CMHTs (shown as stars) are mostly still within the 95% range of assertive outreach scores. The range of scores for assertive outreach clients also includes lower scores.

Discussion

These findings indicate that, in general, assertive outreach is successfully targeting people who fit the criteria set out in the Policy Implementation Guide. With respect to every criterion of severity set out in the guidance, the case-loads of assertive outreach teams had significantly higher scores than the average for community mental health teams before the study. It should be noted that care coordinators in assertive outreach teams rated most of the scales, and this might introduce bias in favour of greater severity, given the purpose of these teams. However, measures that are less subject to rater bias, including homelessness and detention in hospital, also support the inference of greater severity in the assertive outreach case-load.

There is a threshold at about 5 on the M3 scale at which the proportion of assertive outreach clients begins to exceed the proportion of CMHT clients (Fig. 2). This might indicate that this score could be used to inform the auditing of outreach case-loads, to ensure that these do not retain users who could be supported by CMHTs. The aim of discriminating between users above and below this threshold might be to maximise the efficiency of mental health services, since the low case-load requirement of assertive outreach teams clearly makes their unit costs higher, and this resource is deemed more appropriate for users with more complex problems. Equal weighting is given to all 18 items on the M3 relating to mental disorder, risk, adherence to help offered and social needs. However, a score of 5 on the M3 might typically indicate that, in addition to having a severe mental health problem, a person has moderate-to-severe problems in several areas of daily living, poses a risk of violence or self-harm or has problems with drugs or alcohol.

The evidence presented here is drawn from geographically overlapping CMHT and assertive outreach case-loads. Bearing in mind that the areas covered by the CMHT surveys are only part of that covered by the outreach survey, and that the data were collected earlier for the CMHT surveys, the contrast between the CMHT case-loads and the outreach case-loads in the region is striking. If contemporary data had been collected from neighbouring CMHTs for all the assertive outreach teams, we would expect to see even greater differences in case-load severity, given the mission of these teams to deal with more intractable service users, leaving generally cooperative clients on the case-loads of CMHTs. This ‘division of labour’ was not in operation at the time of the CMHT case-load surveys; at that time the hard-to-reach service users were either on the CMHT case-load or not engaged at all.

The sample survey of 24 London assertive outreach teams’ case-loads (Reference Priebe, Fakhoury and WattsPriebe et al, 2003) examined case notes over an interval of 9 months, comparing 391 ‘ established’ with 189 ‘new’ service users in receipt of outreach in 2001. If we compare the total London sample at baseline with our own assertive outreach population survey, there are a number of similarities. Both had similar proportions of male clients (64.5% in London, 65% in the North East), of a similar age (37 and 38 years), of whom the majority were single (72% and 70%). However, the London sample was weighted towards people from minority ethnic groups, so the proportion of White clients was small (45% compared with 90% in the North East). Different rating scales were used for alcohol and drug misuse or dependency, making comparison difficult.

Of course, cross-sectional descriptions of assertive outreach case-loads tell us nothing about the effectiveness of the teams, which have been brought in to prevent service users from ‘falling though the net’ of community care. Harrison & Traill (Reference Harrison and Traill2004) found that consultant psychiatrists were most concerned about service developments taking place at the expense of existing teams. Although the North East survey confirms the effectiveness of the assertive outreach approach in recruiting the most severely impaired users of mental health services, it also raises a number of questions. How has change in case mix impacted on CMHTs? How have the new teams affected, not just the kinds of clients cared for by CMHTs, but also the kinds of work they undertake? What impact has there been on recruitment and retention of staff in existing services? As the new mental health services have developed, have they taken staff from pre-existing teams? These questions also apply to early intervention and crisis resolution or home treatment teams. Further research on service change should therefore use similar methods and approaches to those described here, applying them to the whole system within local mental health and social care communities.

Declaration of interest

This research was commissioned by the North East Assertive Outreach R&D Consortium.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.