Article contents

Probabilistic Causality and Multiple Causation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 March 2022

Extract

I shall argue in this paper that although much attention has been paid to causal chains and common causes within the literature on probabilistic causality, a primary virtue of that approach is its ability to deal with cases of multiple causation. In doing so I shall try to indicate some ways in which contemporary sine qua non analyses of causation are too narrow Cand ways in which probabilistic causality is not) and refine an argument by Relchenbach designed to provide a basis for the asymmetry of causation.

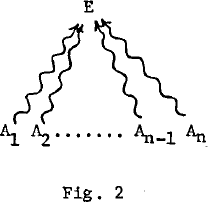

In his contribution to this symposium (Salmon 1981) Professor Salmon has emphasized the central role played by processes and interactions in causality. Whereas his discussion of common causes naturally has a futuristic orientation using causal fans of the type given in Fig. 1.,

I shall be rather more backwards-looking and concentrate on the advantages that probabilistic causation possesses for the analysis of multiple causes of the type in Fig. 2.

- Type

- Part I. Probability and Causality

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1981 by the Philosophy of Science Association

Footnotes

This paper is a revised version of one presented as part of a symposium on probabilistic causality. The other symposiasts were Nancy Cartwright and Wesley Salmon. The original paper was read in my absence by James Fetzer.

References

- 4

- Cited by