Interest group scholarship increasingly describes legislative committees as crucial to any theoretical explanation of group influence in Congress (Hall 1996; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; Powell Reference Powell2013). Committees are where the majority of bills are written (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2008). The preponderance of bills that become law are written by reporting committee members (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2008). Committee members also have gatekeeping powers that other legislators lack (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009). Adler and Wilkerson’s (Reference Adler and Wilkerson2008) work underscores these assertions. In a study of the power of committees to set agendas, Adler and Wilkerson demonstrate that “a mere 1% of bills circumvent (the committee) process.” Moreover, “members of the committee of referral sponsor about 80% of the bills that their committee reports, and these bills have about an 80% chance of passing the chamber, compared to a 7% chance of passage for bills in general” (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2008, 33, but see also Adler et al. Reference Adler, Feeley and Wilkerson2003). Committees therefore play a strong role in devising much of the final content of bills and they have substantial gatekeeping power over the policy agendas under their jurisdiction.

Recent empirical work has further emphasized the importance of committee level allies to which interests win and which interests lose in the legislative process. In a comprehensive study of nearly every type of resource that could affect policy outcomes Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009) found that groups with more legislative allies on House committees were systematically more likely to win policy outcomes. This was a novel, but puzzling finding in their study. Financial resources did not have a clear relationship with policy outcomes. In contrast, groups with a larger number of allies on legislative committees were more likely to report that they received what they were seeking from lobbying Congress. Given these findings, I decided to seek out a position as a fellow on House committees to observe how committee staff and groups interact with one another at an important stage of the legislative process. As a Natural Resources Committee fellow for the minority party staff in the 115th Congress, I could directly observe whether the empirical work that underlies scholarly explanations about the role groups play in the legislative process lines up with the reality of how staff work with organized interests.

Do prominent empirically backed assertions in the interest group literature align with real world experience? Throughout my time working for the committee I set myself to the tasks of paying attention to any evidence that contrasted with or confirmed academic evidence; learning any details that would enrich what we already know about the role groups play in the legislative process; and noting anything that academic work has yet to discover. The remainder of this essay will discuss salient assertions from the literature on interest groups in greater detail and then give examples that detail when my experiences working for the Natural Resources Committee confirmed findings from interest group scholarship and when they ran against current empirical work.

COMMITTEE STAFF AND ALLIED GROUPS

Organized interests are thought to work through legislators with mutual policy concerns because (1) organized interests have policy expertise and legislators require information to make policy decisions (Austen Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992; Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; and Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1996), (2) it is extraordinarily difficult for interest groups to get attention for most policy issues and interests must work through motivated policy champions to build momentum for their legislative agendas (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Mahoney and Baumgartner Reference Mahoney and Baumgartner2015; DeGregorio Reference DeGregorio1997; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006) and (3) interests can increase advocacy for allied legislators by acting as extended staff or service bureaus (Bauer, Pool, and Dexter Reference Bauer, de Sola Pool and Dexter1965; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006).

Extending upon a number of these explanations, Hall and Deardorff’s (Reference Hall and Deardorff2006) theory of lobbying as a legislative subsidy offered a detailed model that accounts for the tangled complexity of mixed empirical findings in the interest group literature. They argue that groups sometimes attempt to persuade legislators to change their voting behavior through the exchange of contributions or information, but this behavior is relatively rare. Instead, they state that interest groups primarily work through legislators in Congress who are the most likely to advocate for their policy needs. Further, Hall and Deardorff emphasize that the policy agenda in Congress is not limitless. Members of Congress have a finite amount of time and resources to dedicate to a subset of issues. It is therefore exceedingly difficult for any group to get members to pay attention to their policy needs, much less to spend time advocating for their policy positions. A fruitful strategy for most groups, then, is to bolster the advocacy of legislators who have mutual policy goals.

In line with Bauer, Pool, and Dexter’s (Reference Bauer, de Sola Pool and Dexter1965) view that interests act as service bureaus to legislative allies, Hall and Deardorff describe interest group lobbying behavior as an attempt to increase legislative advocacy for their policy agendas by subsidizing the effort of their allies in Congress. Groups can subsidize the effort of their natural allies in Congress by offering policy expertise, writing speeches, amendments, or entire pieces of legislation, and assisting with coalition building, among other actions. Recent work has even argued that “virtually all of the applications of other sorts of resources are made in an effort to increase an organization’s supply of these allies” (Leech et al. Reference Leech, Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki and Kimball2007).

Empirical work created since Hall and Deardorff detailed this theory seems to confirm their assertions. Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009) find that one of the few predictors of systematic policy success for organized interests is the number of midlevel allies (e.g. legislators on House Committees, particularly ranking members, committee, and subcommittee chairs) they have. The empirical work therefore offers a substantial amount of evidence in support of the assertion that organized interests predominantly achieve their goals by working through their existing allies in Congress.

How well does this evidence align with what Natural Resources Committee staff do on a daily basis?

To my experience, committee staff make use of allied interest groups wherever groups can help the staff advocate for their view of particular issues more effectively. “The groups” broadly, are a constant part of the discussion of the logistics of particular committee work. Staff do not rely on the work of any one group for assistance, but will work with particular groups repeatedly as the kaleidoscope of issues before the committee is refocused on a group’s area of expertise.

Staff worked overwhelmingly with allied groups and rarely met with representatives of groups that were not directly aligned with committee issue positions. Several examples follow. First, committee staff kept a contact list for groups. While the jurisdiction of the committee spanned issues relevant to a wide variety of business and trade interests, there were no business or trade related groups on the list. Instead it included groups one would expect to be aligned with the ranking member’s party, ideology, and policy positions. Examples included many environmental groups with policy expertise across a host of granular issues under the committee’s jurisdiction. (The committee has jurisdiction and a subcommittee focused on issues of interest to the resource extractive industries.) While the list did not include business interests, it did include labor unions.

Second, the committee maintains checklists detailing the steps staff need to take to successfully implement common committee tasks. Interaction with “friendly” groups is a salient part of the actions senior staff take when they organize hearings, when they prepare for legislative markup sessions, and when they organize action on the House floor. These explicit directions within commonly used roadmaps to committee action provide further evidence that groups acted as extended staff in the manner that Hall and Deardorff describe. They also offer additional insight into precisely when staff will coordinate with groups in ways that subsidize committee work.

The checklists describe what staff ought to do over the timeline of common tasks. Once minority staff receive informal notification of a future hearing, for example, they should contact friendly interest groups and ask them to identify potential witnesses. Two weeks before the hearing, staff should also forward the notice of the hearing to friendly groups. For legislative markup sessions, checklists ask staff to alert friendly groups several days before the date of the markup. Moreover, they instruct staff to contact advocacy groups for suggestions for people with compelling stories about how they might be affected by the bills under consideration. These stories, when appropriate, are included in the remarks made by the ranking member or other members in their comments during the markup session. Furthermore, when legislation under the committee’s jurisdiction is headed to the House floor, staff should also notify relevant groups. Allied groups are therefore an essential extension of the committee staff team. Staff leadership clearly see friendly groups as having an important role in each of these prominent committee activities.

Documents like lists of groups or committee task checklists assist our broader understanding of the role groups play to committee work. In addition to gaining insight into documented processes, I was also able to directly observe several committee staff/group interactions. At the outset of the 115th legislative session committee staff invited allied groups into an all-hands-on-deck meeting to ensure that the committee and allied interest groups were working effectively at advocating for mutual policy concerns. The diversity of the allied groups present and the nature of the meeting made it clear that group/staff interactions were decentralized. Staff could call on groups for assistance as needed, but long-term planning was likely to be more difficult. One reason for this was that the minority staff were not in control of the committee agenda, so they would have little say (and often little notice) about the specifics of future hearings. From the committee’s point of view, groups would continue to bolster the staff wherever group assistance made staff efforts more effective.

Groups also play a central role in the process of finding and, to a lesser extent, preparing witnesses for committee hearings. I observed this through firsthand experience. Staff will identify groups with expertise over the issue(s) relevant to the legislative hearing and then contact the group to get suggestions for hearing witnesses. Once witnesses are selected, the same groups can also assist the committee with witness preparation, such as helping to polish testimony. The committee does not have resources to pay for witnesses to travel to Washington, DC so groups may also fund witness travel if they do not live in the DC area.

Information sharing is constant, but groups will often be called upon as policy experts to help prepare staff for hearings. A day or two before an oversight or legislative hearing committee staff will hold a meeting to provide detailed information about the upcoming hearing to legislative staff. Allied groups with granular expertise will often join committee staff at these meetings to make issue relevant presentations to legislative staff. The policy expertise of allied groups is useful to committee staff because even senior committee level staff cannot become an expert on every issue under their purview. Committee staff are highly knowledgeable about the issues under the committee’s jurisdiction, but groups have the luxury of focusing deeply on a narrow set of issues. They can employ researchers and staff who spend nearly all their time working on a small handful of topics. Members of Congress do not have the resources to hire experts on each narrow policy issue area that they may want to act upon. However, organizations often have issue area experts at the ready. These experts are essential references to legislative staff working on tight deadlines to provide this information to the members they serve. Organized interests provide information to staff as needed on an ongoing basis.

Committees also lack resources to pay for detailed public opinion surveys that parse out public support for different policy positions. Some allied groups assisted staff with this highly useful information. At the beginning of the legislative session, Natural Resources Committee minority party staff (as well as staff of democratic legislators who might advocate for natural resources related issues) received a detailed breakdown of recent surveys that described where the public agreed or disagreed with the Democrat’s policy positions. The group also tested multiple messaging approaches and provided evidence that the public would be more supportive when staff used particular phrases. On the committee, staff made use of this targeted evidence-based language to maximize the effectiveness of messaging on their side of various policy debates. The committee received periodic survey data from a handful of groups throughout my time as a fellow.

Do committee staff primarily use allied organized interests as extended staff as Hall and Deardorff and others describe? My experiences as minority party staff fellow wholly support this theory. Of course, legislative and political context may shape this view as I detail in the final section of this essay.

COMMITTEE REPRESENTATION IS LIKELY TO SHAPE WHO WINS AND LOSES

Committee membership may be biased such that the interests of some groups have more allies on the committee while others have fewer allies. With more allies on House committees the policy positions of some groups may receive outsized advocacy from what we might expect were the committee representative of the full House membership. The literature studying the composition of committee membership has largely focused on a set of research questions that examine how and why the committee system was created. Within this academic debate, scholars have found evidence that members of Congress often request committees to serve constituents and through this service they will better position themselves to win future elections (Adler Reference Adler2000, Reference Adler2002; Adler and Lapinski Reference Adler and Lapinski1997; Shepsle Reference Shepsle1978; Shepsle and Weingast Reference Shepsle and Weingast1987). Adler and Lapinski (Reference Adler and Lapinski1997) argue, for example, that members often self-select on to committees that help put them in the best light for future voters. To this end, legislators will request and then gain membership on to committees that allow them to claim credit in their districts for policy advocacy in support of local constituencies (Adler Reference Adler2000, Reference Adler2002; and Adler and Lapinski Reference Adler and Lapinski1997). And this self-selection process causes some committees to be unrepresentative of the full democratically-elected House membership. As such, these authors argue that these committees may skew policy away from the desires of the full House membership and toward the constituency-motivated desires of a subset of legislators. This literature finds pervasive evidence that committees are often composed of “preference outliers,” meaning that committees are disproportionately composed of members with a strong constituency stake in the policies over which the committee has jurisdiction.

My own work extends this proposition to study how particular groups may benefit (or become penalized) by biases in committee representation (Parrott Reference Parrott2016; Parrott and Lee Reference Parrott and Lee2016). I argue that some groups have more legislative allies on congressional committees than others because these groups have constituency ties in more congressional districts than other interests. I find that if we examine constituency representation on congressional committees at the group level it becomes clear that some groups have systematically better representation than others. With more allies on congressional committees I argue that these groups will gain greater leverage than other groups over policy outcomes.

How well does this evidence align with representation on the Natural Resources Committee?

At the beginning of the session, after the committee roster was finalized, I was fortunate to sit in on the formal subcommittee selection process for the minority. The details of that process were as follows. All minority party committee members met in the committee chamber to formally request subcommittee leadership and subcommittee assignments. The selection process moved forward by seniority. More senior members had the first choice over their assignments. The selection process was directed by the ranking member with assistance from committee staff. (The ranking member, Raul Grijalva, was reappointed to the position by House leadership.)

A new position, the vice-ranking member, was requested, voted upon, and assigned first. Representative Jared Huffman was unopposed and approved to the position via voice vote without objection. Subcommittee ranking member positions were requested, voted upon, and assigned second. Members who held these positions in the previous Congress were first allowed to continue as ranking members in the 115th Congress if they wanted the job. Rep. Huffman was reappointed to lead the Water, Power, and Oceans subcommittee. Rep. Lowenthal was reappointed to lead the Energy and Mineral Resources subcommittee. Reps. Hanabusa, Gallego, and McEachin requested to fill vacant subcommittee leadership positions for the Federal Lands, Indian, Insular and Alaska Native Affairs, and Oversight and Investigations subcommittees respectively. All three were appointed to ranking member positions. And finally, subcommittee placements were requested and assigned in order of seniority.

While I observed that some members clearly wanted to be a part of the committee and others seemed less enthusiastic about their placements, one thing was clear, several members were likely placed on the committee because their constituents would be affected by the issues under the jurisdiction of the committee. Raul Grijalva’s district is home to Native American reservations and a substantial amount of federal lands. Jared Huffman’s district includes a disproportionate amount of environmental organizations and activists compared to other House districts. It is also above the 95th percentile in employment for germane industries like agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting. The same is true for other minority members. Jim Costa’s district is above the 95th percentile compared to employment for the full membership of the House in these industries. Darren Soto represents a district that has a large Puerto Rican population and is above the 80th percentile in these industry categories. Evidence for these kinds of constituency connections are not difficult to find.

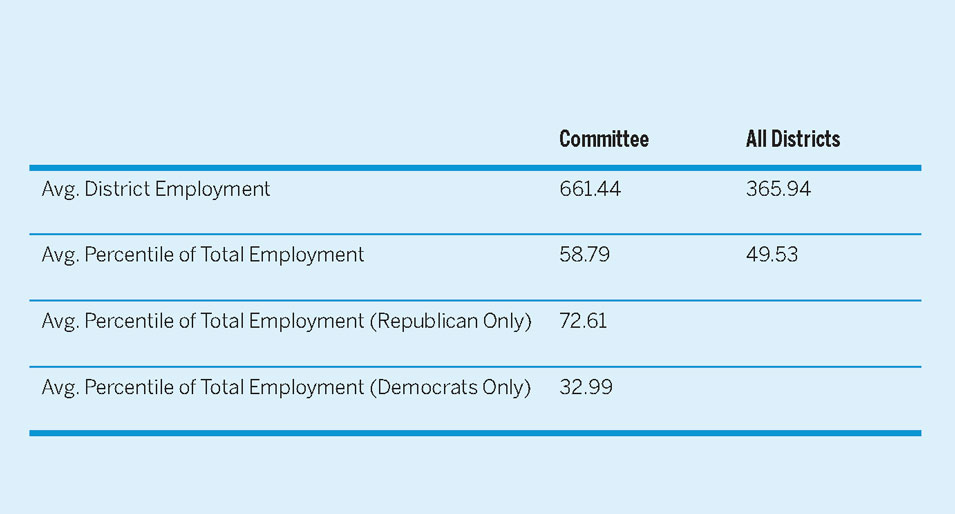

To provide a rough assessment of whether the committee might overrepresent particular interests under its jurisdiction, I tabulate district level employment in agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting for committee member districts versus all House districts in table 1 . This quick tabulation of constituency employment offers some suggestive evidence that the Natural Resources Committee overrepresented particular interests. Committee members had nearly twice the level of employment in these industry categories over and above the average House member. On the Republican side there were 10 members at or above the 90th percentile compared to all House members. And there were 15 members at or above the 80th percentile of employment in these categories. Nearly 70% of majority members were from districts that overrepresented constituencies tied to these industries. In my own work I detail more granular differences in over- and underrepresentation of constituencies tied to particular groups. I found that some groups were likely to have leverage over the policy making process over other groups as a result of these sometimes dramatic differences in committee representation. My direct observational experience working as committee staff only strengthened my belief in this hypothesis.

Table 1 Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting Employment per District

Note: District employment data gathered from Census’s most recent County Business Patterns Survey (2016).

THEORIES OF LOBBYING AND LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT

Three prominent theories have been put forth to explain how lobbyists achieve policy success. In short, scholars have tested whether (1) lobbyists affect policy outcomes by exchanging campaign contributions for legislative advocacy (see selected studies by Bronars and Lott Reference Bronars and Lott1997; Frendreis and Waterman Reference Frendreis and Waterman1985; Grenzke Reference Grenzke1989; Langbein and Lotwis Reference Langbein and Lotwis1990; Stratmann Reference Stratmann1991; Reference Stratmann1995; and Reference Stratmann1998; Wawro Reference Wawro2001; Wilhite and Thielman Reference Wilhite and Theilmann1987; and Wright Reference Wright1985), (2) they use expert information to persuade legislators who are fence sitters or are opposed to their issue to shift the direction of advocacy (Austen Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992; Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; and Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1996), or (3) (as previously discussed in detail) they primarily work to bolster the advocacy of legislative allies with mutual policy concerns (Hall Reference Hall1998; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; and Hall and Wayman Reference Hall and Wayman1990; and Hojnacki and Kimball Reference Hojnacki and Kimball1998). Which theory parallels firsthand experience of lobbying for minority committee staff?

How well does each theory align with lobbying on the Natural Resources Committee?

As others have pointed out, issue salience and legislative context are key considerations (Hojnacki et al. Reference Hojnacki, Kimball, Baumgartner, Berry and Leech2012). My time on the minority staff for a House committee provides some relevant contrasts to the experience of a previous fellow who worked in a much different legislative context (Drutman Reference Drutman2010). This contrast in experience provides an opportunity to make note of potential differences we may find in empirical studies of lobbying across different legislative contexts. As an APSA fellow, Lee Drutman worked in the Senate on salient legislation for the majority party. He worked in the personal office for Senator Chris Dodd, the coauthor of the Dodd-Frank financial bill and the former chair of the Senate Banking Committee. Drutman was a fellow as Dodd-Frank was being developed and he was a part of a subset of staff with a focus on financial issues. In this role he met with many lobbyists as a representative for the Senator’s office on this salient legislation for a Senator with leverage over the content of the bill.

In this context, he witnessed no support for exchange theory, the idea that campaign contributions affect legislative behavior. No lobbying organizations attempted transactional quid pro quo behavior. During my time on the committee working for the minority staff I also found zero evidence for exchange theory. Drutman did, however, have meetings with many lobbyists who attempted to make their case for their side of issues tied to what would become the final bill. For example, several organizations sought to inform the senator of their side of particular issues even when the senator did not typically advocate on their behalf. Put differently, he saw a lot of evidence for lobbying from groups who were not obvious policy allies for Senator Dodd.

As a fellow for minority committee staff, I saw very few examples of lobbying from interests who were not legislative allies with the ranking member or subcommittee ranking members. Committee staff generally had an open-door policy to all groups, so the opportunity for meetings was available. Moreover, I did meet with a handful of interests that were simply bringing information to the attention of committee staff on particular issues. But these instances were rare with respect to groups that did not share the committee’s policy goals.

To my experience legislative context is therefore likely to matter a great deal to the kind of lobbying activity scholars will see in tabular data. Lobbying through legislative allies will be prominent across most legislative contexts (e.g., whether a member is in the majority or minority; or whether a member is working on a committee or introducing legislation among other roles in the legislative process). However, we should see less evidence of lobbying as persuasion in less salient legislative contexts. When bills are not near passage, when individual members have less power to pass bills, or when bills are likely to have a small impact on few interests in society, we will likely see more allied lobbying and less persuasion lobbying.

PARTICIPATION ON HOUSE COMMITTEES

Committees are comprised of a subset of members who are often unrepresentative of the full democratically-elected membership of the House. Biases in representation likely benefit the policy goals of some interests and undermine the goals of others. A related question in the interest group literature that is central to our understanding about the role of groups in the legislative process is the extent to which legislators participate on committees. Scholars have pointed out repeatedly that members have a limited amount of time to spend on any particular activity such that they must prioritize their legislative participation across a large number of issue areas. A host of empirical work has presented evidence that relatively few committee members do the bulk of the work for any given issue (for extensive review see Hall Reference Hall1998). Richard Hall’s theory of participation in Congress detailed a theory that draws from these findings. He found that while most members show up for formal committee markup sessions, few members make speeches on bills. Even fewer members will offer amendments to a given bill. And fewer still will offer amendments that substantially change a given bill. It follows that bill-shaping behavior at the committee level is largely accomplished by a handful of legislators. Hall’s work draws from surveys of legislative staff, but scholars have also confirmed this theory by surveying interest groups (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009). If few members do the bulk of the legislative work as bills are shaped in congressional committees, then some groups with a few key legislative allies may still be well-positioned to win an outsized influence over policy outcomes.

How well does this theory align with participation on the Natural Resources Committee?

Variation in legislative participation was one of the easiest hypotheses to validate as a fellow. Corralling members to do committee work was a weekly part of the job for committee staff. The machinery of the legislative process requires certain things to happen. For legislation to move forward, committee staff need members to speak on the House floor, to formally introduce bills, attend hearings, make speeches, and pose questions to witnesses. Organizing committee hearings and getting members to attend them is therefore an important part of the job. Committee staff will spend a large amount of time organizing both legislative and oversight hearings. Yet on any given issue, it is common for no more than two or three members in addition to the ranking member to show up and take a strong stance during a committee hearing.

The workhorses for the committee were the chairman and ranking member, the vice-ranking member, and the subcommittee chairs and ranking members. As minority staff, my observations were largely focused toward ranking and minority members. The ranking member attended all investigative and legislative hearings for the full committee. He made opening statements and officiated the hearing along with the committee chair. It was also not uncommon for the ranking member to attend subcommittee hearings. In a similar fashion, subcommittee ranking members officiated over subcommittee hearings along with subcommittee chairs. Like the ranking member for the committee they also made opening remarks. These members also were more likely to pose amendments to bills than rank and file committee members.

Participation of rank and file members, however, varied widely. For full committee markup sessions, members were required to show up for all votes and could not vote by proxy. Members received vote suggestions from the committee staff and by and large members voted along party lines. Occasionally members took contrary positions, most often due to constituency concerns. For subcommittee hearings that did not require attendance I do not recall a single hearing where every rank and file member showed up. Typically, the subcommittee ranking member would make opening statements, then two to four members would have a set amount of time to pose questions to witnesses. This lack of attendance was not trivial. The minority received time to question witnesses in approximate proportion to the number of members who attended each hearing. Fewer members meant less time making the case for or against some issue before the American people (or the press who cover these issues).

Some issues saw more attendance than others. For example, when the majority scheduled hearings with the goal of arguing against the Endangered Species Act, the minority membership tended to have many members at the table. For a subset of issues, we would see more members show up and several members would advocate strongly against the majority stance on the issue. On the whole, my personal experience therefore strongly supports the academic assertion that legislative participation will vary widely among committee members.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Despite much academic effort, untangling the role that groups play in affecting the policy making process has proven no easy task. The study of interest groups has transitioned from being central to our understanding of American politics to becoming a relatively small subfield (Baumgartner and Leech Reference Baumgartner and Leech1998). Even so, a number of scholars have pressed on through the complicated bramble of potential null findings to uncover several lines of consistent evidence that, bit by bit, may lead us to a new empirically-driven explanation of the role that groups play in influencing policy outcomes.

It is a rare opportunity to be able to become fully embedded in the world that you usually study through the distant lens of tabular data. As an APSA congressional fellow I was able to observe the day-to-day interactions among interest groups and committee staff. For several months in the winter, spring, and summer of 2017 I worked alongside the minority staff of the Natural Resources Committee. Throughout a rich daily experience, I took in as much information about the role of interest groups from the perspective of committee staff as I could. In this article I have discussed the ways in which this real-world experience supports, adds to, or goes against the prominent evidence-based work from congressional scholars with interests in the role that groups play in affecting policy outcomes at a crucial stage in the legislative process.

During my time as a fellow I was able to confirm several prominent academic assertions through direct observation. First, committee level legislative advocacy, rather than roll call voting behavior, is crucial to our understanding of the role that groups play in the legislative process (Adler and Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2008). Second, groups predominantly work with allied members who have the same policy goals rather than using their resources to affect the advocacy of uninterested members, fence sitters, or opponents (Bauer, Pool, and Dexter Reference Bauer, de Sola Pool and Dexter1967; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). Moreover, the number of legislative allies that an organized interest has in Congress is among the most important resources for groups seeking to influence the legislative process (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009). And the number of allies that groups have on committees is likely to be particularly important to policy success. Third, committee representation will benefit some groups over and above others (Parrott Reference Parrott2016; Parrott and Lee Reference Parrott and Lee2016). And fourth, studying legislative participation (i.e., whether members show up, speak, vote, or offer amendments) rather than voting behavior alone will continue to reveal further insights into the effect that groups have in the legislative process (Hall 1996).