“Populism” is a widely used label for a diverse group of political parties and movements around the world. Researchers apply it equally in political analyses of far-right politics in Western and Eastern Europe, leftist movements in Latin America, and movements such as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street in North America. Commentators use it extensively to describe recent events, from the Brexit referendum to the victories of far-right parties in Poland and Hungary and the popularity of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the recent US election.

Electoral campaigns are fertile grounds for the promotion of populist ideas, and the American election of 2016 is no exception. In this context, Donald Trump has been labeled “the populist par excellence” (Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver, Rahn and Bartels2016). Comparative analyses of announcement speeches during the electoral campaign show that Sanders relied more on a critique of economic elites, whereas Trump used simple rhetoric of anti-elitism, nativism, and economic insecurity to make a strong populist claim to the presidency (Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver, Rahn and Bartels2016). By addressing the economic and cultural concerns of the white working class and their declining societal position, the political rhetoric that Trump used in his campaign speeches contributed to his success (Lamont, Park, and Ayala-Hurtado Reference Lamont, Park and Ayala-Hurtado2017).

Using a content analysis of the campaign speeches of the main presidential candidates, Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser (2018) made important headway in measuring populist rhetoric across the political spectrum in the 2016 campaign. They found that compared to levels of populism in Greece and Venezuela, populism in the US election was moderate, with Sanders and Trump engaging in such discourse with different levels of consistency.

These studies significantly improve our understanding of how political candidates use populist rhetoric in their electoral campaigns. Yet, there is still much to learn about the role that different forms of formal campaign communication played in promoting populist ideas on both sides of the political spectrum in the 2016 American election.

This article makes a twofold contribution to this research agenda. First, it draws on the populism literature as a category of rhetorical claims and proposes a typology of populist claims expected in contemporary American politics. Second, by identifying specific themes that could inform populist rhetoric on both sides of the political spectrum, it tests empirically whether this typology holds in the case of the 2016 election. This article provides fresh evidence from a textual analysis of official campaign communication through Twitter and press releases by the top three presidential candidates: Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Donald Trump.

WHAT IS POPULISM?

Scholars across the social sciences engage in debate regarding the nature of populism and whether it is a form of political mobilization (Jansen Reference Jansen2011; Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011; Weyland Reference Weyland2001), an ideology (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), or a type of discursive frame (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Poblete Reference Poblete2015; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). Despite important differences separating these traditions, scholars agree on many fundamental features of populist movements.

At its core, populism is a type of political rhetoric predicated on the moral vilification of elites, who are perceived as self-serving and undemocratic. Ultimately, populism proclaims the existence of a crisis caused by elites, seeking to challenge the dominant order and giving voice to the collective will (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015; Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver, Rahn and Bartels2016; Pappas Reference Pappas2012; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014). Regardless of their ideological preferences, populists promise to replace the existing corruption with a political order that puts the “people” back at its center and resonates with their longings and aspirations. Populists consider any claims to economic, political, or cultural privilege unfounded and a direct threat to the common wisdom of the people (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Kazin Reference Kazin1995; Lee Reference Lee2006; Panizza Reference Panizza and Panizza2005; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014; Stanley Reference Stanley2008; Taggart Reference Taggart2000). Müller (Reference Müller2016) proposed a set of necessary conditions to ascertain whether populism exists: (1) anti-elitism that reaches beyond simple opposition to incumbent parties; (2) anti-pluralism that provides a credible justification of the “us–them” distinction within a particular society; and (3) an adequate socioeconomic situation with large gaps between groups.

At its core, populism is a type of political rhetoric predicated on the moral vilification of elites, who are perceived as self-serving and undemocratic.

Right-wing populists’ view of the people often is infused with nationalism and nativism. The people are pure and share an identify through belonging to one nation, or “heartland” (Taggart Reference Taggart2000), from which minorities and immigrants often are excluded (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2013). Seen as the silent majority whose interests are overlooked in favor of arrogant economic elites, corrupt politicians, and minorities (Canovan Reference Canovan1999), the people are promised a return to an imagined golden age of racial and ethnic purity, unlimited prosperity, and protection from self-interested politicians.

Bonikowski and Gidron (Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016) found that in electoral campaigns, candidates who view themselves as political outsiders are more likely to rely on populist claims. They use a distinctive rhetorical style that is emotional, simple, direct, and often indelicate (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi, McDonnell, Albertazzi and McDonnell2008; Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Moffitt and Tormey Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014). Their lack of decorum and predilection toward flaunting the usual rules of authenticity make them appear authentic and different from a “typical politician.” The transgressive political style signals to their supporters a strong commitment to protect the interests of their voters, even if it requires breaking the rules (Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver, Rahn and Bartels2016).

Historically in the United States, populism is a common feature of presidential politics among both Democrats and Republicans; in general, it is a strategic tool of political challengers, particularly those who have legitimate claims to outsider status (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016). Despite discursive similarities across the political spectrum, ideology influences the claims that populist politicians seek to advance. Although recent studies shed light on important dimensions of populism in the 2016 election, we are only beginning to understand the complex circumstances that rendered populist rhetoric appealing to American voters in the most recent election.

Drawing from the relevant literature, table 1 proposes a typology of attitudes that contemporary Democratic and Republican politicians are expected to advance when they make a populist claim to political leadership in the United States. On the left side of the ideological spectrum, populists use language that is hostile to the rich, financial elites, and big corporations (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2011; Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017; Plattner Reference Plattner2010). They advance an agenda inclusionary of Main Street and opposed to Wall Street, with a progressive social-justice agenda (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). In general, populist politicians on the left tend to rely primarily on economic claims, whereas politicians on the right favor nationalist claims (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016).

Table 1 Attributes of Populist Claims Across the Political Spectrum in Contemporary US

Source: Compiled by author, from relevant literature

On the right side of the ideological spectrum, populist discourse is producerist and denounces out-of-control spending by government that would benefit freeloaders (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017; Zernike Reference Zernike2010), such as immigrants and members of minority communities (Michael Reference Michael, Jansen, de la Torre, Arato, Ochoa, Roberts and Arditi2014). Providing a racialized interpretation of the people, right-wing populism is intrinsically exclusionary of cultural, religious, linguistic, and racial minorities (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017; Plattner Reference Plattner2010). Voting preferences in the 2016 election also were tied to its timing, at the end Obama’s presidency. Eight years of an African American president magnified a process of racialization of politics (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler, Vavreck and Bartels2016). By 2016, political polarization had become increasingly correlated with race and racial attitudes, to the extent that the Democratic Party increasingly comprised racially liberal whites and minorities, whereas the Republican Party increasingly comprised people who were unfavorable toward African Americans, immigrants, and Muslims (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler, Vavreck and Bartels2016, 67).

The main threat for the people is the “liberal elites,” which work through higher education—particularly Ivy League universities—to “pervert” bureaucrats, judges, and politicians of the future with “un-American” ideas (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). Consternation about the economy, concomitant with fears of demographic displacement due to widespread immigration—mainly from Latin America—stoked the resurgence of populist attitudes on the far right (see table 1). How does this distribution of rhetorical claims map onto the official communication of the top 2016 presidential hopefuls?

POPULISM IN THE 2016 AMERICAN ELECTION

To address this question, I propose a study of official campaign communication through Twitter and press releases. The analysis focuses on official campaign statements (see www.hillaryclinton.com; www.berniesanders.com; and www.donaldtrump.com) as well as tweets published on the official accounts of the three main candidates: @Hillary Clinton, @BernieSanders, and @realDonaldTrump. For six months (January–June 30, 2016), historical campaign statements and tweet data were collected from the three candidates’ webpages and from www.twitter.com. Official campaign statements were published on campaign websites. Twitter is a social-networking platform that allows users to post microblogs or brief entries (“tweets”) that are no longer than 140 characters and usually contain “…short content such as phrases, quick comments, images, or links to videos” (Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan Reference Stieglitz and Linh2013, 219). Since its launch in 2006, numerous politicians have increasingly used social networking for campaigning purposes (e.g., Obama’s use of Twitter during both of his presidential campaigns). The appendix provides details about the method and the coding process, including information about validity, intercoder reliability, the coding scheme, and the frequency of codes for populist themes for each candidate.

Justification for selecting the two means of communication is twofold. First, I am responding to a recent call for more research in the role that media, including social media, play in the process of vote choice (Ernst, Engesser, and Esser Reference Ernst, Engesser, Esser, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and De Vreese2016; Groshek and Koc-Michalska Reference Groshek and Koc-Michalska2017). The comparative perspective across the two media allows us to notice differences and similarities in campaign discourse for mainstream media, targeted by official press statements, and social media, through Twitter. Second, I selected Twitter for the analysis of social media use because the platform is a crucial factor in explaining Trump’s political rise and victory (Galdieri, Lucas, and Sisco Reference Galdieri, Lucas and Sisco2018). I explore further whether Twitter, with press releases, also was a medium to disseminate populist messages during the 2016 electoral race.

BROAD COMPARATIVE PATTERNS

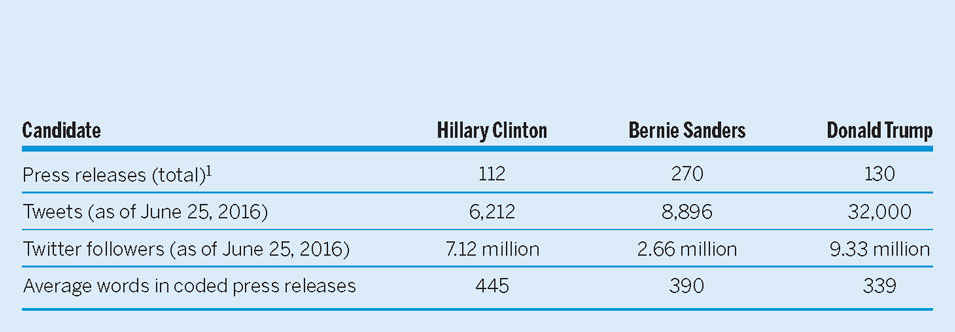

Descriptive statistics of Twitter use and the release of official campaign statements to the press via the campaign websites show clear trends in the prevalence of either medium of communication for the three candidates (table 2).

Table 2 Descriptive User Statistics for Online Campaigns

Hillary Clinton’s campaign used official press releases as a vehicle for presenting different aspects of her policy agenda and positioning it as a continuation of the main policies implemented by the Obama administration and in opposition to the Trump and Sanders future legislative proposals and political direction. The Clinton campaign used Twitter to promote messages that are similar to those promoted in official statements, covering a wide range of topics and taking clear positions on numerous issues (see appendix tables 3 and 4). A better-known political candidate on the national political scene, Clinton chose to make relatively less quantitative use of press releases and tweets. Qualitatively, however, her campaign covered the widest spectrum of topics and issues, representing her as a candidate with extensive political and policy experience.

Trump’s tweets were predominantly critiques—often virulent—of other candidates and much less of a platform to promote policy positions. In other words, the minimal use of press releases allowed Trump to limit the public’s access to clear and elaborate policy positions, as well as strategies to implement them in the event of a successful election result.

The Sanders campaign made significantly more use of official campaign statements to disseminate information about his main policy positions and public campaigning efforts (see appendix tables 3 and 4). The number of Sanders’s statements during the six months covered by this study was more than double and, on average, considerably longer than those issued by the other two candidates. In comparison to the use of lengthier press releases to communicate with the public and the media, his campaign’s use of Twitter was more limited. Arguably, a main goal of the Sanders campaign was to disseminate as much information as possible about a less-well-known presidential candidate; thus, it used press releases as the main medium for written communication (see table 2).

Trump’s use of press releases stands in contrast with Sanders’s; his campaign issued many fewer statements that often contained only one paragraph with an official acknowledgment of support from a public figure. A limited number of official press statements included detailed descriptions of policy proposals. His use of Twitter contrasted both qualitatively and quantitatively with the other two candidates’ communication strategies. Trump made more extensive use of this medium to reach out to voters and also had more than 30% more followers than Clinton and close to 60% more than Sanders. Trump’s tweets were predominantly critiques—often virulent—of other candidates and much less of a platform to promote policy positions. In other words, the minimal use of press releases allowed Trump to limit the public’s access to clear and elaborate policy positions, as well as strategies to implement them in the event of a successful election result. By favoring Twitter use, his campaign limited communication to short and direct statements that favored personal opinions over official policy positions and strategies.

POPULIST RHETORIC IN THE 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNS

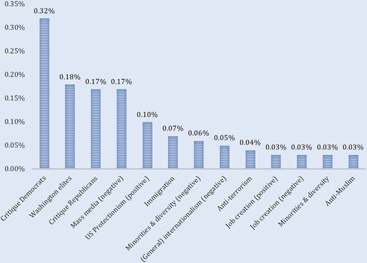

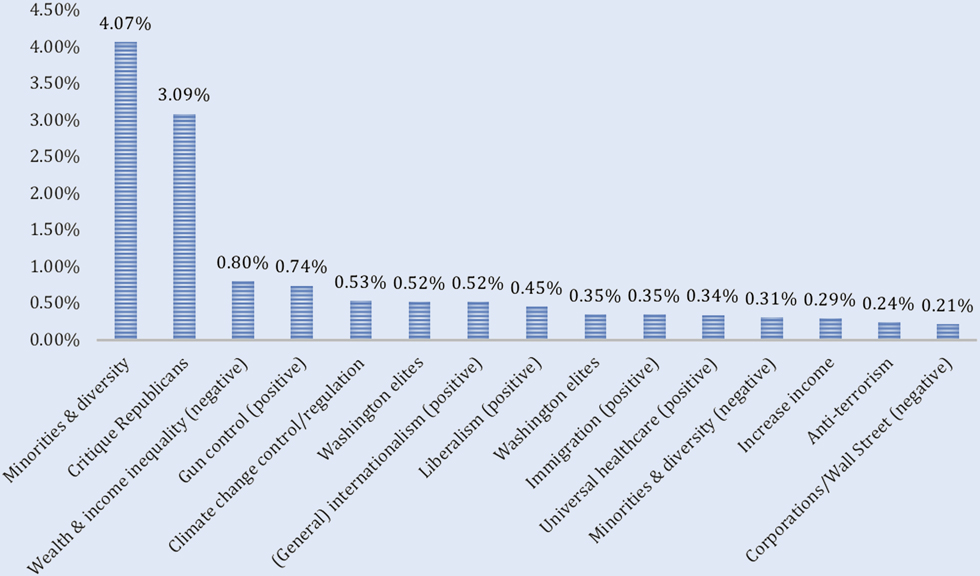

The qualitative-content analysis found that the distribution of themes clustered populist discourse along the left–right axis of ideological position, with Trump’s statements and tweets displaying similarities to the political discourse of the far right. Trump’s discourse in the Twitter-sphere during the electoral campaign showed rhetorical elements of populist right-wing ideology (figure 1). The nativist dimension of Trump’s campaign narrative—perceived as the clear need to strengthen American protectionism in the face of national-security threats such as terrorism, migration, and Islam more broadly—was clear in the most prevalent themes among the codes with the highest frequency. Although not consistently opposed to all types of immigration, Trump made clear his strong opposition to the integration of illegal migration. Stricter controls on migration flows—through legislation, a migration ban, and a wall along the border with Mexico—were essential components of what he considers a sound national security that safeguards against terrorism, job loss, and crime.

Figure 1 Relative Frequency of Most Prevalent Themes: Trump’s Twitter-Sphere (32,000 Total Tweets)

Another element of populism is an anti-elite discourse that builds on the opposition between “the pure people” and the corrupt elites. In often aggressive and disparaging terms, Trump’s discourse was openly critical of political elites in Washington—regardless of their political sympathies. By being different from political elites, he legitimized himself as a better and more reliable presidential candidate.

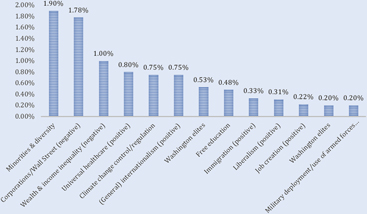

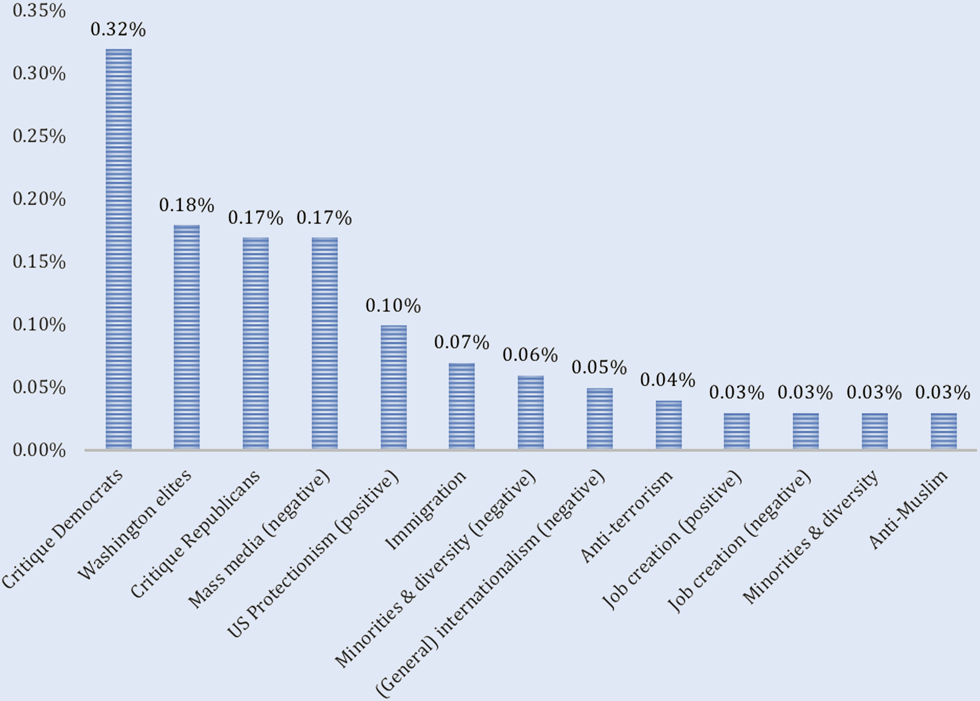

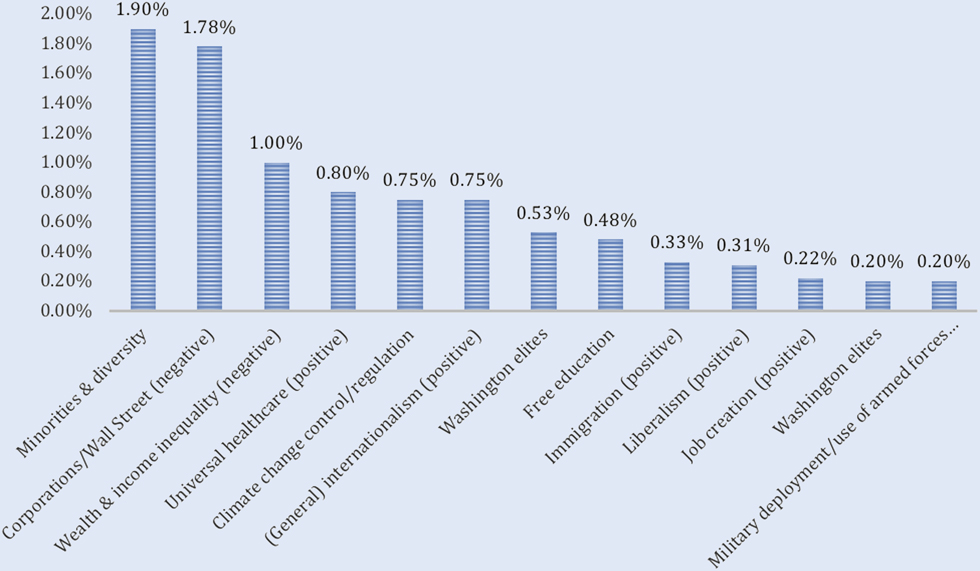

The areas of interest that pervaded Sanders’s official campaign discourse confirmed the expectations set forth by existing scholarship on populism among parties on the left side of the ideological spectrum. Similar to Clinton’s campaign (figure 2) and broadly in line with the Democratic Party’s agenda, gun control, and an open domestic-integration policy toward immigrants were also relevant issues in Sanders’s campaign. In addition to supporting equality and integration of minorities and to promoting openness toward liberal internationalism and diplomatic cooperation, as a left-wing Democratic candidate, Sanders’s discourse was hostile to the rich, the unregulated financial sector, big corporations, and the Washington establishment (figure 3). He explicitly called for a socialist revolution and spoke on behalf of one main excluded social group—namely, “the poor.” According to Sanders, they represent a broad social category whose exclusion is coordinated by Wall Street and corporations, which pursue their financial self-interest and exert significant influence over the political elites in Washington. Moreover, the poor and excluded are victims of unfair income distribution and a system that favors the rich over the poor.

Figure 2 Relative Frequency of Most Prevalent Themes: Clinton’s Twitter-Sphere (6,212 Total Tweets)

Figure 3 Relative Frequency of Most Prevalent Themes: Sanders’s Twitter-Sphere (8,896 Total Tweets)

Whereas Clinton tied income and wealth inequality to differential taxation of the rich and the poor, Sanders proposed a broader narrative of exclusion tied to systemic deficiencies in the contemporary United States. As central themes in Sanders’s campaign, poverty and inequality were best explained by the convergence of several social and economic factors orchestrated by Wall Street, big companies, and Washington elites. Solutions to these problems were also structural and would require profound change in political values, leading to a dramatic social and systemic transformation. Free education and universal health care would allow everyone access to quality education, regardless of income, race, immigration status, or gender. On the international dimension of foreign policy, Sanders’s Twitter discourse proposed the wide use of diplomatic partnership, limiting and aiming to eliminate the use of military power as a response to international conflicts and terrorism (see figure 2).

CONCLUSION

The year 2016 has been called “the year of the populist” and Donald Trump “its apotheosis” (Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver, Rahn and Bartels2016, 190). This study provides new empirical evidence that this is indeed the case. It analyzes official campaign discourse in the official statements and tweets of the top three presidential candidates and shows that a systematic engagement with official campaign press releases and Twitter identified the occurrence of populist discourse in the 2016 US election.

All candidates promoted a populist discourse in their campaign with which they identified in varying degrees during the period included in this study. Trump’s campaign was nativist, producerist, and critical of political liberal elites in Washington. It promoted a racialized view of “the people” and necessarily excluded illegal migrants, Muslims, refugees, and other minorities from his electoral agenda. Sanders’s campaign used populist rhetoric in line with left-wing ideology. He viewed “the people” as poor, largely ignored by Washington political elites, and doomed to a life of inequality by the self-servient economic elite comprising the richest 1% of the population. Inclusive of immigrants as well as other social, cultural, and religious minorities, Sanders advanced a more radical view of a socialist state that offered all citizens free education and health care, eradicating poverty and inequality. Clinton made relatively limited use of populist discourse in her campaign, and the occurrence of populist terms was largely linked to offering responses to the two counter-candidates. Instead, her campaign’s agenda was inclusive of minorities, focused on the middle class, and was liberal in focus, positioning herself as continuing the legacy of the Obama presidency.

This article contributes to existing scholarship on populism as political discourse by exploring the main necessary conditions for populist rhetoric and by testing them on original textual data. Although additional analysis undoubtedly is needed to understand fully the factors that contribute to the public appeal of populist discourse, my data illuminate important patterns about the use of official campaign communication to advance populist claims in the 2016 US presidential campaigns.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651800183X