I want you personally to know I have hated every day in your course, and if I wasn’t forced to take this, I never would have. Anytime you mention this course to anyone who has ever taken it, they automatically know that you are a horrific teacher, and that they will hate every day in your class. Be a human being show some sympathy everyone hates this class and the material so be realistic and work with people.

∼Excerpt from a student e-mail to a female online professor

Are student evaluations of teachers (SETs) biased against women, and what are the implications of this bias? Although not unanimous in their findings, previous studies found evidence of gender bias in SETs for both face-to-face and online courses. Specifically, evidence suggests that instructors who are women are rated lower than instructors who are men on SETs because of gender. The literature examining gender bias in SETs is vast and growing (Basow and Silberg Reference Basow and Silberg1987; Bray and Howard Reference Bray and Howard1980; Miller and Chamberlin Reference Miller and Chamberlin2000), but only more recently have scholars focused on the potential of gender bias in the SETs of online college courses. The use of online courses to measure gender bias offers a unique opportunity: to hold constant many factors about a student’s experience in a course that would vary in a face-to-face format.

The importance of SETs varies among institutions as well as among positions. Even with this variation, SETs can influence decisions on hiring, tenure, raises, and other employment concerns. Moreover, universities that place great emphasis on the results of SETs may be promoting discriminatory practices without recognizing it.

This article explores sources of gender bias and argues that women are evaluated differently from men in two key ways. First, women are evaluated based on different criteria than men, including personality, appearance, and perceptions of intelligence and competency. To test this, we used a novel method: a content analysis of student comments in official open-ended course evaluations and in online anonymous commentary. The evidence from the content analysis suggests that women are evaluated more on personality and appearance, and they are more likely to be labeled a “teacher” than a “professor.” Second, and perhaps more important, we argue that women are rated more poorly than men even in identical courses and when all personality, appearance, and other factors are held constant. We compared the SETs of two instructors, one man and one woman, in identical online courses using the same assignments and course format. In this analysis, we found strong evidence to suggest gender bias in SETs. The article concludes with comments on future avenues of research and on the future of SETs as a tool for evaluating faculty performance.

GENDER BIAS IN STUDENT EVALUATIONS OF TEACHERS

Measuring the impact of instructor gender on SETs can be a difficult task because of the difficulty in controlling for instructor-specific attributes. For instance, if a woman is evaluated poorly by students and a man is evaluated highly, it could be due to gender bias or instructor-related attributes, such as teaching style or overall teacher quality. To address this problem, MacNell, Driscoll, and Hunt (Reference MacNell, Driscoll and Hunt2015) conducted an experiment in which two assistant instructors (one male and one female) each taught two discussion groups of students within an online course, one group under their own identity and another section under the other instructor’s identity. With the ability to give the exact same course material to students and to control for instructor quality, MacNell, Driscoll, and Hunt (Reference MacNell, Driscoll and Hunt2015) found that students in the experiment gave the man’s identity a higher rating than the instructor with the woman’s identity. In a similar research project, Boring (Reference Boring2017) used courses in which students were assigned randomly to a man or a woman professor and then compared evaluations across sections. Her results found that women receive lower scores than men.

The empirical analysis presented in this article confirms these findings and those of other scholars (Martin Reference Martin2016; Rosen Reference Rosen2017). Specifically, our analysis both confirms the existence of bias in SETs within the discipline of political science and contributes to the growing literature that suggests the problem of gender bias in SETs is persistent throughout academia. If SETs are biased against women, as the mounting evidence suggests, then the use of evaluations in hiring is discriminatory.

We contend that women are evaluated differently in at least two ways: intelligence/competence and personality.

EVALUATION CRITERIA OF FEMALE PROFESSIONALS

Gender bias is not only a question of whether male and female professors are evaluated more or less favorably. We argue that women also are judged on different criteria than their male counterparts. We contend that women are evaluated differently in at least two ways: intelligence/competence and personality.

In academia, instructors who are women often are viewed as not being as qualified compared to instructors who are men and, in many situations, they are perceived as having a lower academic rank than men. One reason why women are stereotyped in this manner is that academia is still primarily a male-dominated profession. For example, women who serve as full-time employees are more likely to be in non-tenure-track positions than men (Curtis Reference Curtis2011).

This qualifications stereotype is most evident in situations in which a female professor is incorrectly given the lower rank of instructor by a student and a male professor is accurately labeled as a professor. Although it was not tested in the SETs context, Miller and Chamberlain (Reference Miller and Chamberlin2000) found evidence to support the argument that women are more likely to be viewed as “teachers” whereas men are more likely to be referred to as “professors.” This indicates that students may view a woman as not having as much experience and education or as being less accomplished than a professor who is a man. If this qualification stereotype exists, it should be detectable in SETs and student commentary. Thus, we hypothesize that men are more likely to be referred to as “professors” in their SETs and women are more likely to be referred to as “teachers.”

In addition to the qualifications stereotype, women are more likely to be evaluated based on their personality. Previous studies on gender in academia have found that women were viewed as having “warmer” personalities (Bennett Reference Bennett1982). Furthermore, Bennett (Reference Bennett1982) found that students require women to offer more interpersonal support than instructors who are men. In addition to being described as “warm,” women have been stereotyped as needing to exhibit nurturing and sensitive attitudes (e.g., kind and sympathetic) to other people (Heilman and Okimoto Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007). Consider the excerpt from a student e-mail to a female online professor presented at the beginning of this article: the student specifically requests sympathy from the female professor.

Findings that women are evaluated based on different criteria than their male counterparts have broad implications for women in all professional fields because these systematic differences may not be exclusive to academia.

GENDER BIAS IN STUDENT COMMENTS AND REVIEWS

To begin the research into gender bias in SETs, we first explored whether it is true that students evaluate women using different criteria than men. Our contribution is unique in its use of content analysis to examine student comments about their instructors from two sources. The first source is the comments that students provided at the conclusion of their semester via official course evaluations. The second source is comments uploaded to the popular site, Rate My Professors (RMP), which is a website where students may anonymously post reviews for other students to use when selecting a course or an instructor. Although RMP is not used for hiring or promotion decisions and, of course, suffers from selection bias, consistently poor evaluations in this and similar public forums can have career implications for academics due to lower enrollments in courses or an unfavorable reputation on campus.

If students consistently use different language to evaluate their professors based on gender, it can set the tone for discussions about the quality of instructors who are women. Allowing students to provide open-ended comments about professors—via official or anonymous website evaluations—may create a platform for students to exhibit sexist tendencies, implying that these sexist comments matter. More important, it shows that even younger generations exhibit gender bias and that sexism is not a relic of an older, “good-old-boys” generation.

Each comment was analyzed for the following themes and topics: personality, appearance, entertainment, intelligence/competency, incompetency, referring to the instructor as “professor,” and referring to the instructor as “teacher.”

Each comment was analyzed for the following themes and topics: personality, appearance, entertainment, intelligence/competency, incompetency, referring to the instructor as “professor,” and referring to the instructor as “teacher.” Each theme, including examples of comments within each theme, is described in the appendix, as well as a more detailed explanation of the coding process.

We hypothesize that regardless of the positive or negative nature of the overall commentary on each instructor, a woman will receive more comments that address her personality and appearance, fewer comments that refer to her as “professor,” and more comments that refer to her as “teacher.” We also hypothesize that a man will receive more comments that discuss his intelligence or competency, fewer comments that refer to him as “teacher,” and more comments that refer to him as “professor.”

H1: For categories Intelligence/Competency, Referred to as “Professor”

ProportionMan > ProportionWoman

H2: For categories Personality, Appearance, Entertainment, Incompetency, Referred to as “Teacher”

ProportionMan < Proportionwoman

The percentages of comments that characterized each theme were compared. Results of the content analysis of official evaluations for face-to-face courses are in table 1 and the Rate My Professors content analysis is in table 2.

Table 1 Content Analysis for Official University Course Evaluations

Notes: N = 68; *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Table 2 Content Analysis for Rate My Professors Comments

Notes: N = 54; *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

The official student evaluations of face-to-face courses provided an interesting insight into the words students use to describe male instructors versus female instructors. The results were generally as hypothesized, reflecting that students in official course evaluations apparently use different language in evaluating instructors based on whether they are men or women.

When comments on the RMP website were analyzed, some of the differences between man-versus-woman comments were even more dramatic. Specifically, differences in mentions of appearance were more obvious in an anonymous forum.

Notably, the RMP comments on a woman’s personality tended to be negative (e.g., rude, unapproachable), whereas the official student evaluations tended to be more positive (e.g., nice, funny). In reading the context of each comment, the students mentioning her personality on RMP were almost exclusively taking an online course. Dr. Martin (a man) taught an identical online course during the same period as Dr. Mitchell (a woman). The disparity between comments made by students taking identical online courses led to another line of investigation: an empirical analysis of student ratings of identical online courses with a man versus a woman instructor.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF GENDER BIAS IN STUDENT EVALUATIONS

In spring 2015, both Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Martin acted as instructors-of-record for several online introductory political science courses. The courses and the university are described in detail in the appendix. The only difference in the courses was the identity of the instructor. We compared the ordinal evaluations of a man versus a woman in five sections of the online courses.

VARIANCE ACROSS SECTIONS

We used online courses to compare evaluations because the courses were identical: all lectures, assignments, and content were exactly the same in all sections. The only aspects of the course that varied between Dr. Mitchell’s and Dr. Martin’s sections were the course grader and contact with the instructor.

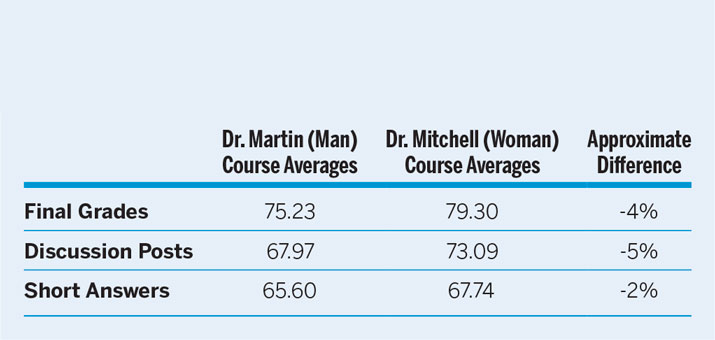

First, each section had a different grader for written work. Although they attended the same training and have the same rubric, some graders had stricter standards than others. Therefore, students may perceive one instructor differently based on the course grader. To determine whether differences in grading may have affected evaluations, we examined grade averages across sections. Table 3 shows grade averages for final grades, discussion posts, and short-answer assignments for both Dr. Martin’s and Dr. Mitchell’s sections.

Table 3 Grading Averages

Although the differences were not dramatic, the data show that grade averages were lower in Dr. Martin’s courses than in Dr. Mitchell’s courses. If students give lower ratings in course evaluations because of lower grades or a perception of stricter grading criteria, then Dr. Martin (a man) should have had lower ratings on his course evaluations than Dr. Mitchell (a woman).

Second, it is possible that one instructor had a more favorable demeanor in dealing with students, either via e-mail or during office hours. Although it is difficult to convey tone in an e-mail, it is possible that Dr. Martin, for example, may have written e-mails differently than Dr. Mitchell. Several examples of e-mails sent by the instructors are provided in the appendix.

EVALUATION DATA

At the conclusion of the semester, students were asked to complete a 23-question evaluation of the course and the instructor as a routine university procedure. Students rated their opinion on each question using a 5-point Likert Scale, with 1 as “Strongly Disagree” and 5 as “Strongly Agree.” Participation in the evaluation process was voluntary.

We first categorized the questions asked in five types. Our contribution is unique in that we separated any question that might have been directly related to instructor characteristics (e.g., sympathy, helpfulness) from those that did not vary across sections. The categories were as follows:

• Instructor: Specific to an individual instructor’s characteristics, such as effectiveness, fairness, and encouragement.

• Instructor/Course: Mentioned the instructor but did not vary across the five sections, such as the instructor’s ability to present information.

• Course: The course itself, including the expectations, workload, and experience.

• Technology: The technology in the course, such as making help and information available.

• Administrative: Registration, advising, or accessibility; the instructors had no ability to control or influence these factors.

ANALYSIS

The ordinal ratings of each instructor in each identical online section were averaged and compared. In the Instructor category, even in identical courses, a statistically significant difference would not necessarily indicate the existence of gender bias. Because these questions could have been influenced by personal characteristics, we offer no hypothesis on the relationship between evaluations of the two instructors in this category.

If students exhibited a gender bias in their evaluation of their instructors, then Dr. Martin (a man) would receive statistically significantly higher evaluations than Dr. Mitchell (a woman) in the categories of Instructor/Course, Course, and Technology. These questions relate to characteristics that are specific to the course; although students may perceive that the instructors influenced them, they do not vary across sections of the course. We predicted that Dr. Martin would receive higher evaluations than Dr. Mitchell in these categories due to bias against instructors who are women.

Because questions in the Administrative category address university-level issues that are not specific to an individual course or instructor, we expected to find no statistically significant difference between the evaluations of Dr. Martin and Dr. Mitchell in this category.

H1: For categories Instructor/Course, Course, and Technology

Evaluation AverageMan > Evaluation AverageWoman

H2: For category Administrative

Evaluation AverageMan = Evaluation AverageWoman

The results of the comparison were astounding. In every category except Administrative, Dr. Martin received higher evaluations, including the non-instructor-specific categories of Instructor/Course, Course, and Technology. Results of an unpaired t-test that was used to determine whether these differences were statistically significant are shown in table 4. Comparison results for individual questions are provided in the appendix.

The data are clear: a man received higher evaluations in identical courses, even for questions unrelated to the individual instructor’s ability, demeanor, or attitude.

Table 4 Unpaired T-Test of SET by Category

The data are clear: a man received higher evaluations in identical courses, even for questions unrelated to the individual instructor’s ability, demeanor, or attitude.

However, perhaps it is possible that Dr. Mitchell was so much worse as an instructor that students, in their ire, rated her lower in all categories—even those that were unrelated to her or her course. This would be a valid critique were it not for the final category of questions: Administrative. These questions asked students to evaluate university-level procedures such as registration and advising. If students were simply unilaterally assigning low evaluations to Dr. Mitchell without considering the question, then the questions in the Administrative category also would have statistically lower ratings for Dr. Mitchell.

On the contrary: in the Administrative category, there was virtually no difference in evaluations. Dr. Mitchell received an average rating 0.25% higher than Dr. Martin, which, as expected, was not statistically significant.

Apparently, students were considering the content of each question when responding and, even in identical online courses with almost no opportunity for variation, they evaluated a man more favorably than a woman. To reiterate, of the 23 questions asked, there were none in which a female instructor received a higher rating.

CONCLUSION

Are student evaluations biased against women, and why does it matter? Our analysis of comments in both formal student evaluations and informal online ratings indicates that students do evaluate their professors differently based on whether they are women or men. Students tend to comment on a woman’s appearance and personality far more often than a man’s. Women are referred to as “teacher” more often than men, which indicates that students generally may have less professional respect for their female professors. Based on our empirical evidence of online SETs, bias does not seem to be based solely (or even primarily) on teaching style or even grading patterns. Students appear to evaluate women poorly simply because they are women.

More important is the question of why this matters. Many universities, colleges, and programs use SETs to make decisions on hiring, firing, and tenure. Because SETs are systematically biased against women, using it in personnel decisions is discriminatory. In addition, this could have broader implications for women in all professional fields.

Research on this issue is far from complete. Our findings are a critical contribution, but more research is needed before the long-standing tradition of using SETs in employment decisions can be eliminated. In addition, bias may not be limited to women. Our future research will examine not only gender bias in SETs but also bias in race, ethnicity, and English proficiency. Women have long claimed that their male counterparts are perceived as more competent and qualified. With mounting empirical evidence that this is true, perhaps it is time that universities use a method other than student evaluations to make critical personnel decisions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651800001X