In 2013, more than 33.5 million Americans played fantasy sports. Forbes estimates that it is a $40 billion to $70 billion industry (Goff Reference Goff2013). Resembling many other booming economic ventures, it is expanding globally. For instance, in England, at least 5.5 million people play fantasy sports; in Canada, 3.1 million play. It is integrated—if not enabled—by the Internet and social media. The fastest-growing demographic is youth: 20% of 12- to 17-year-olds play fantasy sports, compared to 13% of adults. College students also are a target demographic as the popularity of fantasy sports drives rapidly increasing participation rates (Seifried et al. Reference Seifried, Farnet, Turner, Brett and Davis2007). Footnote 1 Fantasy sports are a part of contemporary culture; for that reason, they make an innovative teaching tool. In this article, I introduce “Fantasy Presidents,” an original game based on drafting teams composed of US presidents. The game is brief, fun, and educational. Specifically, preparing, writing about, and debriefing a classroom fantasy draft provide useful ways to generate excitement about political science research.

FANTASY SPORTS: A PRIMER

Fantasy sports allow competitors to build a team staffed with actual sports stars. That team then competes with other teams also staffed with actual sports stars. The winner is determined by whichever team’s players produce the best statistical results. For example, a simple fantasy football league could be based solely on touchdowns. Each team in the league might have five players, and whichever team’s five players score the most touchdowns wins. Although football is the most popular fantasy sport, leagues range from soccer to cricket to Formula One racing. In fact, fantasy leagues now transcend sports. For instance, there are “Fantasy Congress” (i.e., judged on legislative success) and “Fantasy Celebrity” (i.e., tabloid appearances). Footnote 2 PS: Political Science and Politics once published an article that suggested a league for “Fantasy Political Scientists” (e.g., based on publications and conference appearances) (Meier and Stewart Reference Meier and Stewart1992).

Of course, selecting one’s team is the most essential part of the fantasy league. As with actual football, each fantasy player can be part of only one team. To determine which fantasy teams own which actual players, most leagues conduct a draft, in which the teams choose players in an orderly fashion. For example, if Team 1 receives the first pick of the draft, then that team’s owner(s) can choose any actual player available. After Team 1 picks, Team 2 may choose any player except the player chosen first overall by Team 1. After each team has drafted a given number of players, they compete against one another using predetermined scoring systems.

“FANTASY PRESIDENTS”

“Fantasy Presidents” deviates from “traditional role-playing” simulations, in which students assume the roles of political negotiators (Bridge and Radford Reference Bridge and Radford2014). Various scholars have advocated for a new breed of games, including “off-the-shelf” board games (Bridge Reference Bridge2014), “board-game-like” games (Goon Reference Goon2011), and those with “explicit rule-based” structures (Asal Reference Asal2005; Bridge Reference Bridge2013; Raymond Reference Raymond2012, 76). This article adds to those efforts by proposing the use of fantasy drafts.

Using a fantasy draft creates motivated research opportunities and, ultimately, helps students to take ownership in their learning. In terms of rules, “Fantasy Presidents” operates on a basis similar to fantasy sports.

The game is designed to get students excited about researching US presidents. Using a fantasy draft creates motivated research opportunities and, ultimately, helps students to take ownership in their learning. In terms of rules, “Fantasy Presidents” operates on a basis similar to fantasy sports. There are four teams, and each team drafts eight presidents (eleven presidents are undrafted). Team 1 chooses first, Team 2 chooses second, and so on. Each team has 1 minute to choose, thereby guaranteeing that the draft does not take too much class time (i.e., about 30 minutes). To ensure a level of fairness, odd-numbered rounds start with Team 1 and even-numbered rounds start with Team 4. This gives those teams choosing at the bottom of the first round a chance to choose at the top of the second round (table 1).

Table 1 Order of Rounds One and Two, with Examples

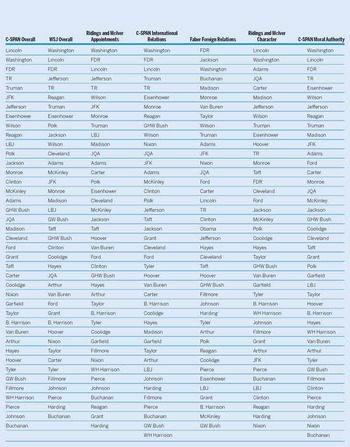

The main difference between fantasy sports and “Fantasy Presidents” is the scoring system. Whereas fantasy sports use objective measures (e.g., touchdowns), “Fantasy Presidents” uses a subjective “rotisserie” method, Footnote 3 in which teams are ranked along a given number of dimensions and then receive points for their respective rankings. After the draft, the instructor can use one of two methods to determine a winner. First, the many polls of scholarly or journalistic rankings of presidents can be referenced to create an average score for each team on any number of dimensions. Footnote 4 For instance, a simple league could judge only the Overall and Foreign Policy categories and then use the Wall Street Journal Overall and C-SPAN International Relations polls to score those categories (table 2). Second, the rosters can be submitted to outside experts, preferably those scholars whose work is related to the presidency. Footnote 5 In this method, one expert would rank the rosters based on Overall composition and another expert would rank them on Foreign Policy records. In both judging methods, first place receives 5 points, second place receives 3 points, third place receives 1 point, and fourth place receives 0 points. Thus, the highest possible score in this example is 10 points (i.e., 5 points for Overall and 5 points for Foreign Policy). The team with the highest combined score wins.

Table 2 Examples of Polls

In running the game a number of times, I experimented with many different dimensions, including Overall, Foreign Policy, Domestic Policy, Bottom Four Picks, Party Managers, Team Chemistry, Liberal, Conservative, Margin of Electoral College Victory, Executive Appointments, and Scandal. I found that the game was the most fun and educational using the following rules.

Four teams each draft eight presidents. Those teams are ranked along six dimensions: Overall, Bottom Four Picks, Foreign Policy, Party Managers, Executive Appointments, and Scandal. Footnote 6 I then use a combination of polls and expert methods for judging. With the Overall category, teams submit their entire rosters for judging; with the Bottom Four Picks category, they submit only their last four choices. Footnote 7 For the other four categories, students select four presidents from their roster to compete on those dimensions—with the provision that each president must be used on two dimensions.

Table 3 displays the winning team from the most recent iteration. Their Overall category ranked second. The team’s four presidents chosen last were Grant, JQA, Harding, and Garfield. With a relatively poor quartet, the team finished last in this category. In the other four dimensions, it assigned each president to two categories. The team focused on winning the Foreign Policy and Scandal categories, which led to solid rosters on those dimensions. Indeed, as it had set out to do, the team won those categories. However, because it had used FDR in Foreign Policy, it could place him only in Executive Appointments or Party Manager. Because FDR was relatively strong on both dimensions, it required a difficult choice: (1) place him in Executive Appointments and sacrifice Party Manager points; or (2) place him in Party Manager and sacrifice Executive Appointments points. The students chose the first option because they felt the rest of their team could fill out the Executive Appointments category better than the Party Manager category. Thus, they concentrated whatever placements they had left in Executive Appointments—which gained them a second-place ranking (i.e., 3 points) on this dimension. Their four Party Manager selections, then, were not based on those presidents’ party-management skills. Indeed, Wilson and Harding were relatively poor party managers. Rather, they happened to be the four presidents not yet been assigned to two categories. Ultimately, this strategy paid off for the team.

Table 3 Example of a Winning Team

BENEFITS AND POSSIBLE ASSIGNMENTS

The most important pedagogical aspect of the game is the research required before the draft. To prepare for the draft, students must conduct background research on presidents in American history. There is no formal assignment leading up to the draft; however, I suggest Milkis and Nelson’s The American Presidency: Origins and Development (Reference Milkis and Nelson2011) as a useful starting point and it is available as an optional text in the campus bookstore. Generally, though, students are neither assigned a reading nor tested on various presidents. Instead, the competitive nature of the fantasy draft sparks their interest in dutifully researching the presidents. In fact, those on the same team often divide the work, with each student delving into a particular era (e.g., the early republic) or a set number of administrations. The main advantage in this is that the game incentivizes students to take ownership in their own learning. Of course, traditional research papers can accomplish the same goal. However, I have found that a fantasy draft encourages students not only to do the work but also to be excited about doing it.

After the draft, a writing assignment helps to debrief and reinforce the students’ research. Although I have used a number of writing prompts, I find two specific assignments to be the most beneficial. In the first, students explain why they assigned each president to their respective two categories. For instance, in the previous example, one student wrote about the FDR dilemma. The essay described how FDR was deemed very good along three dimensions: Foreign Policy, Executive Appointments, and Party Manager. It continued by explaining how winning the draft affected FDR’s omission from the Party Manager category. This type of essay requires students to examine their team’s presidents along all of the dimensions and to identify the combination that best positions them to win.

The most important pedagogical aspect of the game is the research required before the draft. To prepare for the draft, students must conduct background research on presidents in American history.

The second option is for the instructor to select a single pick for each team and then ask that team to justify that pick in light of other available options. In a recent example, one team had to justify their drafting of Bill Clinton when Andrew Jackson was still available. The students wrote that they needed to have a “Scandal superstar,” someone who could headline that dimension. They admitted to being tempted by Jackson, who was a “Party Manager superstar”; that is, they discussed how Jackson brought together a new political party and kept its northern and southern wings in line. However, they believed that “Scandal superstars” were a rarer breed—especially with Richard Nixon already chosen by another team. Moreover, they figured that they could still find good Party Managers later in the draft. In fact, when they drafted Clinton, they reasoned that he could be considered a good Party Manager himself. The essay argued that although Clinton’s first two years were difficult, he reached across the aisle to pass major bipartisan legislation, including welfare reform and the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Both essay assignments require students to research the historical presidency. Again, a standard term paper can accomplish the same task; however, I have found that “Fantasy Presidents” generates more enthusiasm for doing the research. In addition, the papers are easier to grade. For example, instructors can allow a team to submit a single paper rather than an individual paper from each team member. “Free-riding” may be an issue; however, the excitement created by the draft often generates a more equal distribution of work than other group projects. Moreover, grading is more interesting because the papers are quite different from one another. Because each team’s roster contains different presidents, the essays present novel arguments. Furthermore, post-game feedback surveys reveal that students appreciate that the prompts are tailor-made to their own team. In the Clinton/Jackson example, they believed that the instructor designed an essay assignment especially for them.

CONCLUSION

“Fantasy Presidents” is a fun and effective way to teach and learn about American political development. Requiring less than 30 minutes of class time, it fosters friendly competition, encourages and stimulates independent research, and serves as a useful platform for insightful writing assignments. In post-game feedback surveys, the most common criticism is that students believed their team should have been chosen as the best (regardless of whether the poll or expert method was used). Even these complaints, however, lead to productive classroom discussions about the merits of one team versus another. The game is especially useful in teaching students about the historically lower-ranked presidents. Most students are sufficiently knowledgeable about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, but categories including Bottom Four Picks and Scandal encourage them to research presidents such as Zachary Taylor and Warren Harding (see footnotes 6 and 7).

Although the main purpose of this article is to introduce a new game about US presidents, it also contributes a new type of activity to the simulation literature. Fantasy drafts not only heed calls for “explicit rule-based” games (Raymond Reference Raymond2012, 76), they also offer an entirely new line of activities. Indeed, all subfields could adapt some form of fantasy drafts: for example, international-relations instructors could field a global-alliances fantasy draft and “Fantasy Political Theorists” could be judged on levels of democratic inclusion, security, and/or social mobility. If fantasy leagues are already a part of the culture of college students, then using them in the political science classroom can be a valuable teaching tool. Equally important, a fantasy league can excite students to take more ownership in their own education.