Environmental features such as the ‘foodscape’, a contraction of food and landscape, defined as the physical, sociocultural and economic space in which people encounter meals and foods, might be associated with dietary intake and health outcomes(Reference Dixon, Ugwoaba and Brockmann1–Reference Vonthron, Perrin and Soulard3). Different approaches to the foodscape have been identified, and this review focuses mainly on the spatial approach of the foodscape, i.e. all the local shops, markets, restaurants and sales outlets that provide food supplies in a given area(Reference Vonthron, Perrin and Soulard3). In interaction with individual characteristics, the foodscape may be conceptualised both as the existence of adequate supply of food outlets regarding people's need (availability) and the relationship between the location of food outlets and the location of individuals, accounting for transportation resources, travel time, distance and cost (spatial accessibility)(Reference Clary, Matthews and Kestens4). After defined the role of foodscape in the food environment and the different approaches used in literature, this review aims to explore the evidence on relationships of urban foodscape with diet and health outcomes and to highlight the limitations in studying these relationships as well as suggestions in choosing the most relevant methodology for future studies.

What role does foodscape play in the food environment?

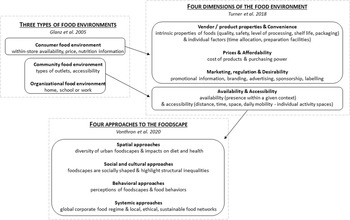

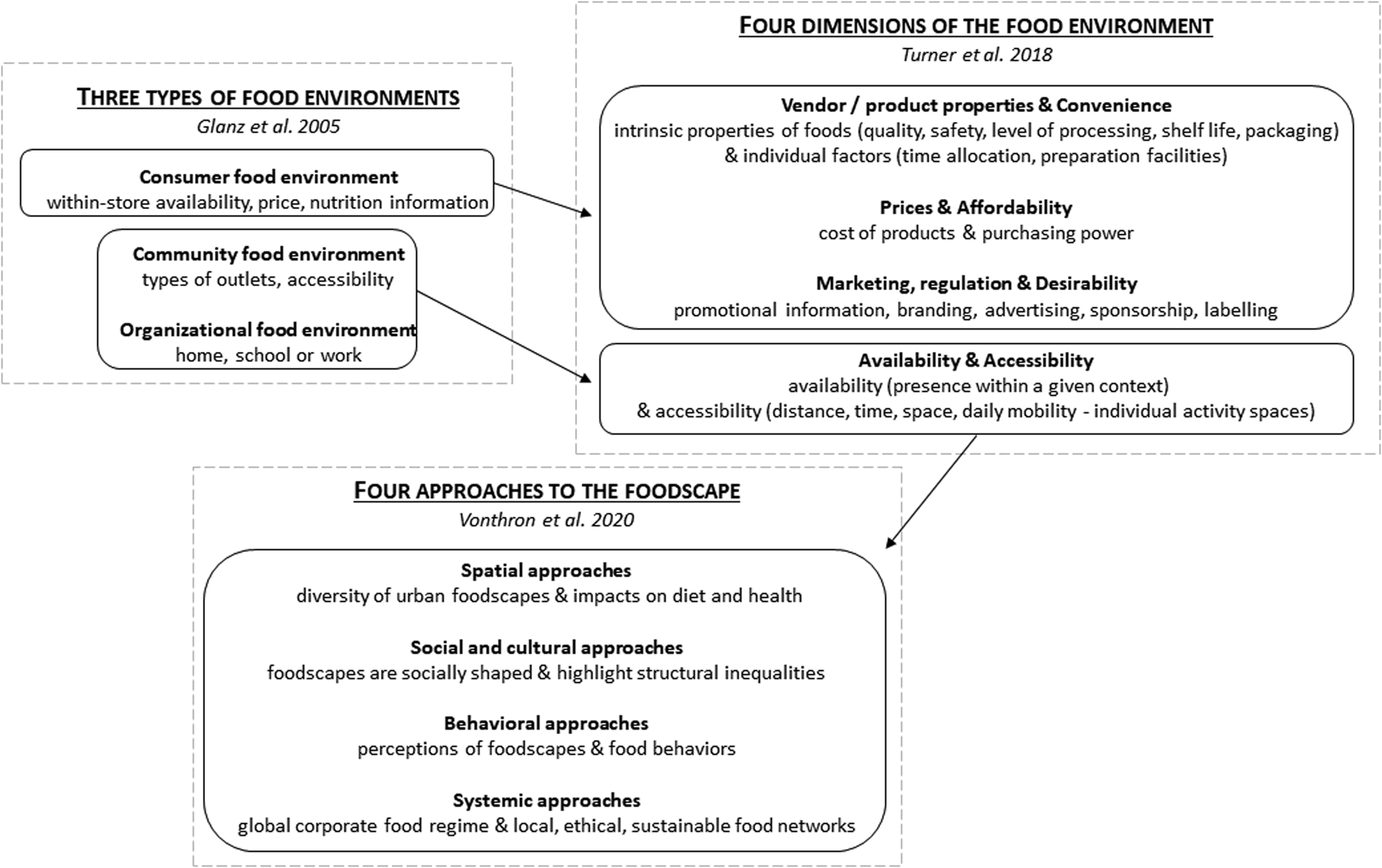

Eating behaviours and dietary intake result from complex interactions between individual and contextual characteristics. In addition to individual factors and socio-cultural and political environment, largely documented, the food environment is a major determinant of diet and eating behaviours. As underlined by Downs et al.(Reference Downs, Ahmed and Fanzo5), the foodscape has a critical role in the food system for implementing interventions to support healthy diets, as it encompasses the full range of options in which consumers make decisions about what foods to buy and eat. Much of the scientific literature defines the food environment by distinguishing the community environment (types of outlets, accessibility), the consumer environment (within-store availability of healthy options, price, nutrition information), and the organisational food environment (home, school or work)(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens6) (Fig. 1). Food environment is characterised by several dimensions in literature. Turner et al.(Reference Turner, Aggarwal and Walls7) propose to conceptualise food environment through four key dimensions that shape food acquisition and consumption (Fig. 1). The first dimension called ‘vendor and product properties and their convenience’ mainly refers to the intrinsic properties of foods such as quality, safety, level of processing, shelf life and packaging and their interactions with individual factors such as time allocation and preparation facilities to determine convenience. The ‘Marketing and regulation’ dimension contains promotional information, branding, advertising, sponsorship, labelling, that influence individual preferences, acceptability, tastes, desires, attitudes, culture, knowledge and skills to shape the desirability of food vendors and products. The third dimension was called ‘prices and affordability’. Prices refer to the cost of food products and interact with individual purchasing power to determine affordability. Prices and affordability vary according to ‘food availability and accessibility’, the fourth dimension. Availability and accessibility are two commonly used dimensions, often conflated within the literature. Availability refers to whether a vendor or product is present or not within a given context and precedes accessibility that is relative to individuals. Accessibility includes distance, time, space and place, daily mobility, and modes of transport that shape individual activity spaces. Foodscape is included in this ‘availability and accessibility’ dimension.

Fig. 1. Definitions of food environment and foodscape.

Spatial approach of the foodscape

The term ‘foodscape’ has been used in various research studies addressing social and spatial disparities in public health and food systems, since the 90's. Vonthron et al.(Reference Vonthron, Perrin and Soulard3) have identified four approaches to the foodscape in literature from analysis of 140 publications (Fig. 1): (1) Spatial approaches characterise the diversity of urban foodscapes and their impacts on diet and health, at city or neighbourhood scales ; (2) Social and cultural approaches at the same scales show that foodscapes are socially shaped and highlight structural inequalities ; (3) Behavioural approaches show how consumer perceptions of foodscapes explain and determine food behaviours and food education; (4) Systemic approaches contest the global corporate food regime and promote local, ethical and sustainable food networks. Spatial analysis is the first and most widely used approach to foodscape. However, socio-cultural, behavioural and systemic approaches are increasingly common. The term ‘foodscape’ is synonymous with ‘food environment’ and particularly ‘community food environment’, in the spatial approach whereas ‘foodscape’ and ‘food environment’ are not synonymous in the other three approaches. Definitions of foodscapes include material issues and also more holistic and socio-cultural issues, but all authors include in the ‘foodscape’ at least the physical spaces and places where food is purchased and consumed.

The growing interest in foodscape follows the historic increase in the obesity prevalence in recent decades. The limited impact of education programs and individual-level interventions has pushed the field of public health to move from a behavioural change to an ecological approach emphasising influences of living environment on health. There were also rising concerns, in recent decades, about social and spatial inequalities in health and food accessibility. In addition, several studies have shown that living in ‘food deserts’, i.e. areas where physical access to food outlets is limited, could be a health issue(Reference Beaulac, Kristjansson and Cummins8). At the same time, the development of technologies in geography such as geographic information systems (GIS) has facilitated the wide-scale production of environmental variables. Finally, in cities of high income countries, food is mostly acquired through market-guided retail systems.(Reference Clary, Matthews and Kestens4). If food choices operate within the limit of what the food system has to offer, associations between the foodscape and dietary behaviours are to be expected.

For the rest of the review, only the spatial approach will be developed because most studies on the effects of the foodscape on diet and health have used the spatial approach. Spatial approaches use statistics and GIS, tools to characterise the diversity of urban foodscapes and their effects on diet and health. In such studies, the term ‘foodscape’ designates a set of places in an area where food may be purchased and consumed (e.g. retail food outlets, markets, restaurants, fast food restaurants, take-away restaurants and also community gardens and food aid structures, etc.). This approach is often used for research in public health, health geography, urban geography and sociology to identify environmental determinants related to diet and health. More specifically, the spatial distribution, i.e. the availability and the accessibility of food outlets, is studied. According to some classifications(Reference Black, Ntani and Inskip9,Reference Ohri-Vachaspati, Martinez and Yedidia10) , food outlets providing a wide range of healthful foods such as fruits and vegetables (FV), like supermarkets, grocery stores and greengrocers have often been considered ‘healthy’ in literature whereas those with limited healthy foods options such as fast-food restaurants are called ‘unhealthy’. A table describing a possible classification of food outlets can be found in Ohri-Vachaspati et al.(Reference Ohri-Vachaspati, Martinez and Yedidia10), where definitions for supermarkets, grocery stores, convenience stores, speciality stores, full-service restaurants, and limited-service restaurants are given. Given the increasing popularity of alternative food supply chains, some food supply sources should be added to this list, namely farmers' markets, organic stores, bulk stores, community-supported agriculture (CSA), as well as delivery services of food baskets with drop of locations, which are rarely considered in recent literature on foodscapes.

Foodscape and its relationships with health outcomes

Much of the research on health and foodscape conducted over the past two decades focused on neighbourhood-level built environment characteristics and their impact on higher obesity prevalence. Most studies were home-centric, i.e. the presence, density or distances to destinations of interest were measured in relation to the individuals' homes. As explained by Drewnowski et al.(Reference Drewnowski, Buszkiewicz and Aggarwal11), who presented the evolution of the measure of foodscape exposure in relation to diet and obesity, early studies combined individual addresses with area-based, sociodemographic data to calculate the presence, number, density, diversity of fast food restaurants or supermarkets per administrative unit. Later studies used specified buffer zones about individuals' home using GIS to assess the distance between the nearest supermarket and individuals' homes. While the proximity, i.e. the distance to the nearest supermarket, can be readily obtained from GIS data, the location of the destination supermarket can only be assessed through a survey.

Drewnowski et al.(Reference Drewnowski, Buszkiewicz and Aggarwal11) in their literature review showed that the evidence on the association between the foodscape and obesity prevalence was inconsistent. They postulated that the inconsistency of the results may be related to the limitations due to the home-centric design of most studies. Firstly, some home-centric studies do not take adequately into account the often confusing effect of the socioeconomic environment in the relationships between spatial characteristics of the foodscape and health outcomes. For example, studies have shown that perceived proximity to fast food restaurants is associated with low residential property value, which is, in turn, associated with higher prevalence of obesity(Reference Drewnowski, Aggarwal and Tang12,Reference Drewnowski, Aggarwal and Rehm13) . Also, there is a lack of clarity in relation to the possible pathways through which foodscape characteristics may influence health. As the interactions of individuals with their foodscape becomes increasingly complex, our conceptual pathways models must also become more complex. Finally, as the investigation of foodscape exposure is often limited to the surrounding residential areas in home-centric studies, such studies hypothesised that proximity to food outlets infer usage and they neglected to consider the influence of other non-residential places that lined to social activities and travel behaviours. The consumer, however, does not necessarily shop at food outlets that are closest to home(Reference Drewnowski, Aggarwal and Hurvitz14–Reference Burgoine and Monsivais17); workplaces, and other frequently visited locations are other potential places to consider(Reference Thornton, Crawford and Lamb16). Environmental influences even go beyond frequently visited places, and need to consider people's mobility, which leads to a shift from place-based measures of exposure, to people-based measures of exposure, which take into account people's daily mobility(Reference Perchoux, Chaix and Cummins18,Reference Kestens, Lebel and Daniel19) . To overcome this limitation, researchers have begun to focus on the activity space, using advanced GPS technologies to assess an individual's mobility in space and time. They determine activity spaces by measuring cumulative mobility over a given time-period, completed by data on travel behaviours (destination, reason for the travel, etc.) to explain the GPS data. The ‘contextual expology’ recently presented as a sub-discipline of built environment research focus on the spatiotemporal configuration of foodscape exposures (spatial and temporal patterns of mobility) for improving measurement of environmental exposures (not the ‘what’ but the ‘where’ and ‘when’ of exposure) and accurate mapping of spatial behaviour(Reference Chaix, Kestens and Perchoux20). It relates to the collection and transformation of locational information to define a spatial ground of measurement and to the extraction and aggregation of environmental information on this basis to derive environmental exposure variables. As underlined by Drewnowski et al.(Reference Drewnowski, Buszkiewicz and Aggarwal11) streamlined, efficient, destination-focused, web-based tools may become the next generation of tools to assess habitual foodscape exposure in long-term studies of weight and diet changes.

For an overview of the literature on the relationships between foodscape and the prevalence of obesity, Lam et al.(Reference Lam, Vaartjes and Grobbee21) have summarised the accumulated evidence by conducting a review of systematic reviews on associations between any aspect of the foodscape, such as presence or density of supermarkets or fast food restaurants and weight status. More research and systematic reviews on characteristics of the foodscape have emerged over the past years, and in their umbrella review, Lam et al.(Reference Lam, Vaartjes and Grobbee21) identified ten reviews that focused, among others, on the foodscape in relation to weight status outcomes but they observed limited evidence on the association between foodscape and weight status of the individual. Only three reviews found that more than 50 % of included studies highlighted findings in the expected direction (such as positive association between density of fast foods and weight status or negative association between supermarkets and weight status, etc.). Wilkins et al.(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris22) conducted the most comprehensive review on foodscape and found 76 % of the associations between foodscape characteristics and adult obesity to be non-significant. The percentage of non-significant associations varied from 74 % when exposure to fast food outlets was studied to 78 % when exposure to convenience stores or supermarkets/grocery stores was considered. Tseng et al.(Reference Tseng, Zhang and Shogbesan23) found no change in BMI in any intervention studies in relation to the foodscape. Interventions targeting both foodscape and physical activity environment also did not result in BMI change(Reference Tseng, Zhang and Shogbesan23).

Most reviews attributed this inconsistency to the great variability of the foodscape characteristics used in these studies, and the components and methods to assess them that make it difficult to make comparisons between studies. Even within the fast food domain, where associations were most consistent, there was much heterogeneity in defining and categorising fast food outlet. Some studies only considered the large fast food chains while other took into account outlets that sell foods high in fat, salt and sugar through fast foods or takeaway outlets. However, when only major franchises are considered, the total number of outlets decreases and therefore false positive or false negative associations may be found(Reference Fleischhacker, Evenson and Rodriguez24). Some authors proposed to define fast food outlets according to the time taken to serve food (e.g. a few minutes), the type of service provided (e.g. counter service only) and the type of foods served (e.g. ready to eat, with limited preparation)(Reference Fraser, Edwards and Cade25). Building consensus on what constitutes fast food outlets could potentially reduce inconsistent findings on fast food. Wilkins et al.(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris22) also concluded in a recent review that a narrower definition of fast food outlets led to more positive associations between presence, density of fast foods or proximity to fast foods and weight status. Conversely, Cobb et al.(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco26) found that composite food outlet measures which combine both healthy and unhealthy food outlets were more consistently associated with weight in adults than measures of single food outlet types. Indices that capture the relative amount of healthy and unhealthy outlets compared to the other outlets (e.g. retail food environment index that computes fast food + convenience food outlets / supermarkets + produce vendors) are the most common composite food outlet indices and they were more likely to be significant and in the expected direction than associations with individual food outlet types. Wilkins et al.(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris22) and Cobb et al.(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco26) also assessed quality of reporting in foodscape studies and concluded that most exposure methodology sections were of low quality. As the dynamic of foodscape in an area is fast, with rapid replacement of outlets by others over the time, the quality of data on foodscape indicators, often based on secondary online and outdated data, for which the lack of reliability was noted by several authors, also explained the inconsistency of results(Reference Gamba, Schuchter and Rutt27). Lastly, although these studies were conducted relatively recently(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris22,Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco26) , it should also be noted that foodscape indicators in an individual's activity space appear to be more predictive of weight status than home-centric-defined characteristics(Reference Drewnowski, Buszkiewicz and Aggarwal11).

Foodscape and its relationships with diet

There is not a direct association between the foodscape and weight status of the individual, rather any association is a distant one. It would be more relevant to focus on the evidence on associations with intermediate, more proximal outcomes, such as dietary behaviours(Reference Drewnowski, Buszkiewicz and Aggarwal11). Any observable relationship between the foodscape and obesity should first, logically, have some observable effect on dietary behaviours. According to Dixon et al.(Reference Dixon, Ugwoaba and Brockmann1) who conducted a scoping review of reviews, fourteen reviews examined the association of the foodscape with a spatial approach, such as presence of food stores and fast-food restaurants, with dietary intake. Fruit and vegetable intake was the most common outcome measure used to assess dietary behaviours in all reviews. A review of qualitative studies highlighted that the lack of accessibility to food outlets due to distance or transportation limitations was key barrier to purchasing and consuming healthy foods whereas results from quantitative studies were mixed(Reference Pitt, Gallegos and Comans28).

Turner et al.(Reference Turner, Green and Alae-Carew29) performed a systematic search of six literature databases for studies assessing availability and access to FV in the retail foodscape and its association with FV intake in adults in high- and middle income countries. The availability was measured by the presence of FV in food stores while the accessibility was assessed by geographical distance between individual's home and food outlets. A positive association of increased availability of FV options in the food outlets was positively associated with FV intake in 9 out of 15 studies. Regarding accessibility, no significant association was found with individual FV intake or household's FV purchase in the large majority of studies whereas positive associations between shorter distance or increased density of food outlets and higher FV intake were found in seven studies when measured using a GIS. Heterogeneity of these results seems to be due to methodological limitations. Differences in the methods used to evaluate accessibility of food outlets that sell FV does not allow direct comparisons and firm conclusions but this review suggests there is a growing body of evidence of a positive association of FV accessibility with FV intake(Reference Turner, Green and Alae-Carew29). In a review of natural experiments, Woodruff et al.(Reference Woodruff, Raskind and Harris30) reported that the opening of a new food retailer such as a supermarket, farmers market or produce stand, tended to produce some short-term increases in FV intake in adults who choose to shop at these stores; however, there was little evidence supporting longer-term effects or broader community impacts on FV intake. In addition, research on fast food restaurants showed that most associations of accessibility of fast food restaurants with FV intake or fast foods intake were NS(Reference Fleischhacker, Evenson and Rodriguez24).

Measuring the overall diet quality using indices such as Healthy Eating Index, Diet Quality Index or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) score, may however be more fitting than intakes of some food groups, since we do not consume separate food groups, but meals with a variety of food groups, where interactions between foods can occur. Conclusions from previous literature reviews on the associations between foodscape and overall diet quality have drawn to mixed results. According to Dixon et al.(Reference Dixon, Ugwoaba and Brockmann1) who included fourteen reviews examining associations between foodscape and dietary intake, five reviews reported associations between greater access to supermarkets and higher diet quality scores while five others reported mainly inconsistent results (including 2 on natural experiments). Also, three reviews reported significant associations between access to fast-food restaurants and lower diet quality, while five others reported mainly inconsistent results. To cite some examples, Bivoltsis et al.(Reference Bivoltsis, Cervigni and Trapp31) in their systematic review highlighted results of a Canadian study where no conclusive association was found between food environment and the Canadian adapted Healthy Eating Index (HEI-C)(Reference Minaker, Raine and Wild32), as well as results from an Irish study where a significant negative association between distance to supermarket and adherence to the DASH was reported(Reference Layte, Harrington and Sexton33). Stevenson et al.(Reference Stevenson, Brazeau and Dasgupta34) focused on studies carried out in Canada, where mostly no association between food environment and diet quality was found. Rahmanian et al.(Reference Rahmanian, Gasevic and Vukmirovich35) reviewed, among others, five studies exploring the relationships between foodscape and diet quality for which only one found no significant association. For instance, two US studies found that greater proximity to supermarkets was associated with better diet quality in pregnant women (DQI-P) (Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Kaufman36) and that participants living in best-ranked food environments were more likely to have a higher Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) score(Reference Moore, Diez Roux and Nettleton37). As explained above for relationships with weight status, most studies are home-centric studies but there is some evidence that indicators of activity spaces are also unrelated to diet quality. Indeed, there is a growing understanding that the foodscape constitutes only a small slice of the larger context of the food environment. The majority of research evaluating relationships between foodscapes and eating behaviours have been conducted in the United States(Reference Dixon, Ugwoaba and Brockmann1). Studies evaluating these relationships in other contexts remain scarce, yet food shopping behaviours are deeply linked with consumers' food culture, making analysis in different geographical settings all the more important(Reference Cairns38,Reference Askegaard and Madsen39) . In France for instance, food shopping is still regularly conducted in a variety of different places, and smaller specialised food stores, such as bakeries, butchers, greengrocers etc. are more abundant in French foodscapes compared to central England's foodscape(Reference Pettinger, Holdsworth and Gerber40).

Limitations in studying relationships between foodscapes and health and diet

There are many publications that assess the associations between foodscape and diet or obesity. A large number of systematic reviews, e.g.(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris22,Reference Fleischhacker, Evenson and Rodriguez24,Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco26,Reference Turner, Green and Alae-Carew29,Reference Bivoltsis, Cervigni and Trapp31,Reference Rahmanian, Gasevic and Vukmirovich35) have sought to examine the research and seek consensus on the topic, but the overall conclusion of these reviews is that the results of studies combining foodscape and diet and health outcomes are very heterogeneous. The publication of Sacks et al.(Reference Sacks, Robinson and Cameron41) studies the methods and results of fourteen systematic reviews on this topic. A number of limitations in the research to date may partly explain the heterogeneity of these results. Firstly, the methodological limits are highlighted: the majority of studies are cross-sectional studies, often concerning the urban foodscape and mainly conducted in the US. Often these studies take into account only one aspect of foodscape, this does not allow to compare study results with each other. Sacks et al.(Reference Sacks, Robinson and Cameron41) also underlined the difficulty of defining exposure measures. Indeed, the foodscape is often only considered about the place of residence of the participants, omitting the effect that foodscape can have about the workplace and other places of activity. Finally, the inconsistent and heterogeneous use of methods, for classification of types of food outlets or defined geographical area to measure proximity or density of food outlets for instance, makes it difficult to interpret findings and evaluate commonalities across studies. There is a large number of different measurement tools, the reliability and validity of which varies and there is a lack of gold standard methods. Following these limitations, Sacks et al.(Reference Sacks, Robinson and Cameron41) made recommendations in order to overcome them. They proposed (i) diversified contexts taking to account local specificities and diversified study designs such as longitudinal studies and natural experiments that take advantage of the circumstances in which relevant changes occur in a given area and population, e.g. an urban transformation project, and then try to plausibly attribute changes in outcomes of interest to the intervention(Reference Leatherdale42); (ii) a foodscape estimated by several composite indicators; (iii) a more complete assessment of foodscape exposure, including workplaces and trips; (iv) the use of standardised methods, tools and analyses.

Future studies to assess how the foodscape influences both, but separately at-home, as well as away-from-home food consumption are warranted and are of interest in this space. Results might vary according to consumption place, which could be an important aspect to take into account. Also, the influence of types of food outlets that provide a more sustainable food supply, such as markets, organic stores and short supply chains remains unexplored, despite the increasing use of these outlets by consumers. Future studies which seek to explore the sustainability aspects of foodscapes, taking into account for instance alternative food supply chains to the industrial food system (supermarkets) with an increasing popularity, such as bulk stores, CSA, delivery of FV baskets and the recent expansion of local farmer's markets, mainly related to the organic movement(Reference Figueroa-Rodríguez, del Álvarez-Ávila and Hernández Castillo43), are needed. In this respect, online food shopping practices should be given special attention to, especially given the food supply concerns that along with the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

Overall, the evidence for associations between foodscape characteristics and diet and health outcomes are mixed. Large heterogeneity and inconsistency in defining the foodscapes and methodologies to measure them explain the inconsistent results. Aspects in the conceptual pathways models, methods, measures, analyses and reporting must be improved to increase our understanding of the relationships of foodscape with weight status and diet in future studies(Reference Sacks, Robinson and Cameron41). In particular, the assessment of the foodscape must expand beyond individual's home foodscape to include other places of activity and travels between places. Studies assessing the relationships of the foodscape with weight status need to take into account mediating effects of dietary behaviours, socioeconomic status and individual factors such as perceived foodscape in these pathways. More natural experiment studies, as a real-world approach(Reference Leatherdale42), designed to explore causality should be conducted in order to test the suggested effects of observational studies. Such research informs about how people engage with their foodscape and may consecutively help in the decision-making process concerning public health actions designed to improve the foodscape, including actions that might contribute to decreased social inequalities with regard to diet. Foodscapes provide very interesting opportunities to shape consumer behaviour, since they are at the centre of consumers' decision making concerning foods to purchase and to eat. Based on research results, politics may better understand and improve the impacts of their commercial urban planning strategies (e.g. market and shop installations) on the diets of the people living in their area, by regulating the occupancy of public spaces, while also retaining ownership of certain commercial premises in a bid to preserve food shops and also by developing transport policies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Nutrition Society and the French Nutrition Society (SFN) for their invitation to the plenary lecture in the 3rd International symposium on nutrition: Urban food policies for sustainable nutrition and health.

Financial Support

This work was carried out as part of Daisy Recchia's Ph.D. funded by Région Occitanie and Institut National de Recherche pour l'Agriculture, l'Alimentation et l'Environnement (INRAE). The funders had no role in the decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

Caroline Méjean and Daisy Recchia reviewed the studies for the plenary lecture and wrote the paper.