Implications of migration on the development of nutrition-related non-communicable diseases

The past few decades have seen a surge in the number of African migrant populations living in Europe and other high-income countries (HICs)(Reference Fanzo, Haddad and McLaren1,Reference Connor2) . Since 2010, migrants from Africa are estimated to account for about 80 % of the ten fastest growing populations of international migrants(Reference Connor3). African migrants who move from sub-Saharan Africa to HICs experience higher levels of nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NR-NCDs) including hypertension, obesity and type 2 diabetes than their host populations, with important differences by sex observed(Reference Agyemang, Meeks and Beune4). The risk of NR-NCDs among these populations also differs according to country of origin, country of destination and duration of stay in the host country(Reference Agyemang and van den Born5). For instance, the research on obesity and diabetes among African migrants study(Reference Agyemang, Beune and Meeks6,Reference Agyemang, Beune and Meeks7) found that African migrants residing in England had a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes than those residing in the Netherlands and Germany (Fig. 1). Obesity was also found to be higher among African migrants residing in England compared to those residing in the Netherlands and Germany (Fig. 2). The prevalence of NR-NCDs is not only higher compared to host country populations, but there is also an increased risk among migrants compared to their non-migrant compatriots living in their country of origin(Reference Agyemang, Meeks and Beune4,Reference Boateng, Agyemang and Beune8) .

Fig. 1. Type 2 diabetes among Ghanaian migrants and Ghanaians living in Ghana: age-standardised prevalence of type 2 diabetes by locality in men (a) and women (b). Error bars are 95 % CI(Reference Agyemang, Meeks and Beune4).

Fig. 2. Obesity prevalence among Ghanaian migrants and Ghanaians living in Ghana: age-standardised prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) by locality in men (a) and women (b). Error bars are 95 % CI(Reference Agyemang, Meeks and Beune4).

This surge in NR-NCDs among African migrants has been associated with the nutrition and health transition, changes in the food environments and diets following migration(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Mohindra and Booth10) . The idea that the food environment may be associated with the increasing prevalence of NR-NCDs is not new. For instance, in 2007, the Foresight report(Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman11) was commissioned by the UK government to illustrate the complexity of factors influencing obesogenic dietary (and physical activity) behaviours, including in people's food environments, but this was not developed through the lens of migrant-origin groups. Food environments include physical, economic, policy, and socio-cultural surroundings, opportunities, and conditions that influence people's food consumption patterns and acknowledge them as determinants of health(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Vandevijvere12). Migration to an HIC is also accompanied by changes in the physical environment and the adoption of dietary behaviour of the host country(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell13,Reference Holdsworth, Nicolaou and Langøien14) , which have been associated with the risk of CVDs, obesity and type 2 diabetes(Reference Boateng, Agyemang and Beune8,Reference Osei, van Dijk and Dingerink15) .

As a response to this rising burden of NR-NCDs, the WHO recommends preventive strategies that target underlying modifiable behaviours such as dietary behaviours and social determinants through the creation of healthier food environments(16). However, knowledge of the differential ways in which food environments may influence unhealthy dietary behaviours among migrant-origin groups living in HICs is limited. This difference is important because disparities in dietary behaviours between ethnic groups and/or between migrants and the host population are well documented(Reference Méjean, Traissac and Eymard-Duvernay17,Reference Raza, Nicolaou and Snijder18) . These wide variations in dietary behaviours could be due to variability in the operation of factors in the food environments such as social networks, socio-economic status (SES) and acculturation level among migrant-origin groups(Reference Jonsson, Wallin and Hallberg19,Reference Roberts, Cavill and Hancock20) .

Dietary acculturation

The process of acculturation (Table 1) presents several challenges and life changes that could have potentially positive or negative effects on the health of migrants via changes in lifestyle, including diet. Several studies have explored the association between acculturation and diet(Reference Raza, Nicolaou and Snijder18,Reference Pan, Dixon and Himburg21–Reference Sturkenboom, Dekker and Lamkaddem23) , but the influence of acculturation on dietary behaviours is still not properly understood. Inconsistencies in the association between acculturation and dietary intake are reported in the literature(Reference Sturkenboom, Dekker and Lamkaddem23,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24) , and has been attributed to several issues including methodological considerations, such as variations in the way dietary intake is conceptualised and assessed(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24). The process of change from traditional diets (often characterised by whole grain, fruits and vegetables and associated with multiple health benefits) to new patterns of diet (often associated with an energy-dense westernised diet) is often referred to as dietary acculturation(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9) (Table 1). Evidence from some dietary studies among migrant-origin groups living in the USA(Reference Kim and Chan25) and Canada(Reference Satia, Patterson and Kristal22) have shown that dietary acculturation includes the adoption of a high-fat diet and low intake of fruit and vegetables. These examples are of public health concern because dietary patterns characterised by high-fat and low fruit and vegetables are risk factors for NR-NCDs.

Table 1. Definition of concepts

Models of dietary acculturation

Two main models have been proposed to explain the factors influencing dietary change in migrant populations(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9,Reference Kockturk-Runefors26) . Their scope, strengths and weaknesses are discussed next.

The first dietary acculturation model was proposed by Kockturk-Runefors(Reference Kockturk-Runefors26) and aimed to enhance the understanding of adaptation to new dietary patterns after migration. This model seeks to explain how food habits change depending on taste preferences and cultural identity. In this model, foods are grouped into staple foods, complementary foods and accessory foods. Staple foods are foods that form a dominant portion of the diet for a given population, and staple foods vary among different population groups. They usually are a source of carbohydrates and proteins. For most Africans, living within Africa or in HICs, popular staple foods are made from starchy carbohydrates such as cassava, yam, plantain and rice. Complementary foods are often protein-rich sources such as meat, fish, legumes and milk. Accessory foods are added to enhance the taste and presentation of the meal(Reference Kockturk-Runefors26).

According to the model, staple foods are likely to remain the same for several generations, however accessory foods change most easily on exposure to a new food environment, whereas complementary foods may remain unchanged over a long period. Kockturk-Runefors argues that if staple foods remain the same following migration, changing accessory foods is still perceived by migrant-origin groups to preserve the identity of the meal as the ‘traditional diet’ (Table 1).

Although the model developed by Kockturk-Runefors was based on observations of food habits of Turkish migrants in Sweden, studies in Europe have tested its usefulness(Reference Méjean, Traissac and Eymard-Duvernay17,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24,Reference Nicolaou, Doak and van Dam27) . An example is a study among Moroccans in the Netherlands that showed that Moroccan migrants tend to consume more sweets and snacks following migration(Reference Nicolaou, Doak and van Dam27). Another dietary change study, focusing on Ghanaian migrants, found a shift from a more traditional fish-based diet to a diet higher in dairy, red and processed meat, which can be seen as a more westernised dietary pattern following migration(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24). In contrast to Kockturk-Runefors's model, the Ghanaian study also found a shift from traditional staples (plantain roots and tubers) to bread and cereals following migration, which suggests that staple foods are the last to change following migration. What this may mean is that when people migrate, foods perceived to be close to one's identity are still important in the sense that these foods are still consumed, but their relative importance to the food groups may change or be ‘diluted’ by other foods(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24).

Additionally, Kockturk-Runefors purports that there is a similar differential change in meal patterns, i.e. breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks, where initial changes are seen with snacking or grazing, because snacks are often not considered as real foods by migrant groups(Reference Mellin-Olsen and Wandel28), similar to the perception of accessory foods. This is followed by changes in breakfast, then lunch. The model further indicates that dinner, usually remains unchanged for so long because family members are more likely to come together at the end of the day. Therefore, there is more social, cultural and ethnic significance to eating dinner compared to lunch and breakfast. This could be compared to staple foods remaining unchanged for so long because of its strong ties with ethnicity. For instance, in a study of Ghanaian migrants, breakfast habits had shifted towards those of the majority ‘host’ population, which is consistent with the model, while the evening meal still had cultural importance, and family members were more likely to be around at the end of the day or during the weekends. Other studies have also found a similar process of change among migrants(Reference Mellin-Olsen and Wandel28,Reference Tuomainen29) .

The second model of dietary acculturation, developed by Satia-Abouta and colleagues(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9), illustrates the complex relationship that exists between cultural factors (e.g. religion), socio-economic factors (e.g. employment), demographic factors (e.g. sex) and migration, and how this impacts different patterns of dietary intake. According to this model, change in dietary intake due to migration is not a simple or linear process where migrants make a discrete shift from traditional foods to the host diet or to westernised diets. Instead, change in dietary intake could take different pathways. It can be in the form of completely abandoning traditional diets or maintaining traditional diets, or to combining traditional diets with the host diet due to various reasons.

These different outcomes of dietary acculturation are in line with Berry and Sam's classification of acculturation strategies(Reference Berry, Sam, Berry, Segall and Kagitcibasi30). For instance, maintaining some traditional dietary behaviours and adopting new ones from the host country could be described as a sign of integration. The departure from traditional diets has been reported in some studies in the UK and France, especially among younger generations of migrant-origin groups(Reference Gilbert and Khokhar31). On the contrary, studies among Afro-Caribbeans living in Manchester(Reference Mennen, Jackson and Sharma32) and Ghanaians living in London, Amsterdam and Berlin showed the maintenance of traditional diets, even after several years of living in the UK(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24,Reference Galbete, Nicolaou and Meeks33) . This is supported by another study conducted among Ghanaian migrants living in Greater Manchester who were described as having bi-cultural dietary patterns, indicating that they neither completely changed traditional dietary practices to that of the host country or completely maintained traditional dietary practices(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34). In this study, three typologies were identified similar to the three patterns demonstrated in the model of dietary acculturation(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9), namely the maintenance of traditional eating patterns; the adoption of host country eating patterns and bicultural eating patterns. However, Satia-Abouta's model implies a strict division within the three patterns, whereas this study found evidence of an overlap between dietary typologies and nuances in bicultural dietary practices. This finding is consistent with those from previous studies of Ghanaians in the UK(Reference Tuomainen29) and female migrants from different African and Asian countries living in Norway(Reference Garnweidner, Terragni and Pettersen35).

Most dietary acculturation studies have investigated the process of change from traditional to new patterns of diet (i.e. westernised diet), suggesting a change from healthy to less healthy diets(Reference Gilbert and Khokhar31). However, recent studies among Ghanaian migrants propose that migration may contribute to healthier or unhealthy dietary changes(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34). A study conducted among international students in Belgium also reported increases in the consumption of healthy foods following migration(Reference Perez-Cueto, Verbeke and Lachat36). Exposure to host food culture through the media, friendships and the work environment were hypothesised to result in increased nutrition knowledge, which in turn led some migrants to adopt healthier diets. This contradiction in the influence of migration on dietary practices confirms the idea that dietary acculturation is a complex process that depends on several factors. The operant model of acculturation and ethnic minority health behaviour(Reference Landrine and Klonoff37) may go some way to explaining these seemingly contradictory findings. An implication of the varying perceptions regarding a change in dietary practices resulting in healthy/unhealthy dietary practices is that it is possible that within the Ghanaian population not everyone will require the same kind of intervention(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Boateng and Danquah24).

While Satia-Abouta's model of dietary acculturation discussed earlier is useful for nutritionists to understand dietary acculturation, its limited inclusiveness and lack of accounting for the many other factors that influence dietary practices following migration have been criticised(Reference Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister and Flórez38,Reference Antin and Hunt39) . It is largely based on traditional migration models and considers dietary change from the perspective of relatively disadvantaged communities. Migration is often assumed to be from an underprivileged situation to a more prosperous country, and that the resultant dietary change is therefore from an implied healthy, traditional diet, to a more westernised and less healthy one. This limits its relevance to more recent voluntary migrant groups or migrants from a high SES background before migration(Reference Thomas40), thus it may not be relevant for future migrant generations, i.e. second-, third- or fourth-generation migrants. Once again this emphasises the importance of considering the heterogeneity of migrant populations.

One limitation of Satia-Abouta's model(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9) is the separation of factors into socio-economic, demographic and cultural factors, which tends to present a simplistic view of the process of dietary change that is more complex than the model suggests. Other factors that have been shown to influence dietary practices such as contemporary migration patterns and those of the globalisation of the food system are not included, for example(Reference Fanzo, Haddad and McLaren1,Reference Thomas40) .

How the food environment influences diets among African migrants

A range of models and frameworks(Reference Holdsworth, Nicolaou and Langøien14,Reference Turner, Aggarwal and Walls41–Reference Constantinides, Turner and Frongillo44) have been developed to explain the role of food environments in people's diets, given the influence of food environments on nutritional quality of the diets people consume(Reference Holdsworth and Landais45). However, contextual differences across populations may limit transferability of existing frameworks to African migrants who may purchase, cook and consume different meals as compared to the host population.

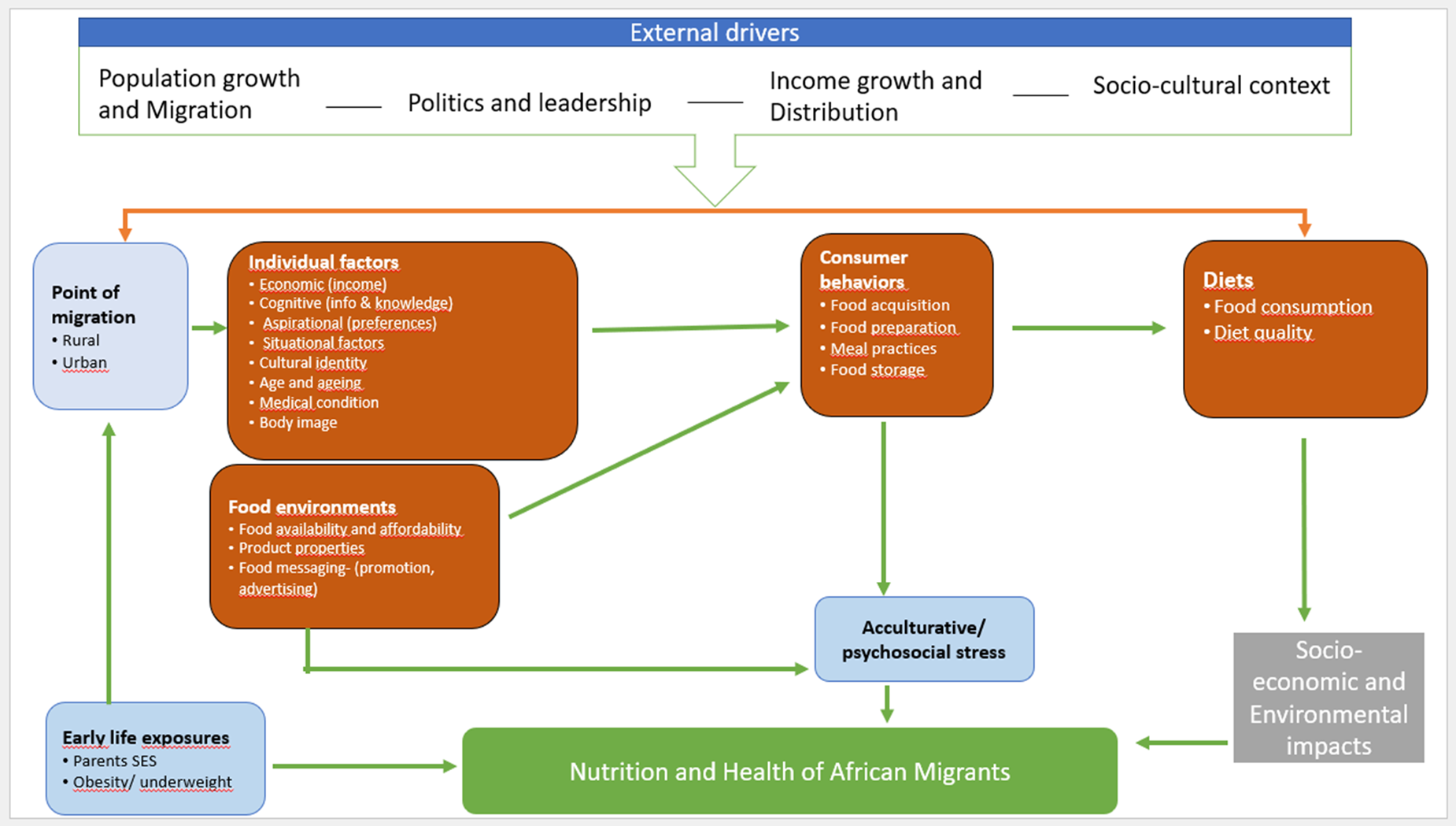

We used a food systems framework(Reference Fanzo, Haddad and McLaren1) to structure the discussion of the food environment and other relevant factors influencing the change in dietary behaviours following migration. In our adapted framework (Fig. 3), the external drivers that influence the diets of African migrants are population growth and migration, politics and leadership, income growth and distribution and the socio-cultural context. These directly influence the African migrant's food environment, consumer behaviours and individual factors, such as economic and situational factors. In this section, the evidence of these immediate drivers that directly shape the health and nutrition and socio-economic outcomes of food systems of African migrants in the UK are examined and discussed.

Fig. 3. Adapted food system framework influencing nutrition and health outcomes of African migrants (adapted from HLPE(87)). SES, socio-economic status.

Food supply chain

As shown in Fig. 3, the food supply chain comprises food production, food storage and distribution, and food marketing. These activities and associated actors are responsible for production, consumption and disposal of its waste(Reference Hawkes and Ruel46). Unlike other food supply chains, that for traditional foods of African migrants is more complicated, given that most of these are imported into Europe. It is well known that the level of food production influences food availability and affordability, which also in turn influences diet quality and diversity(Reference Lartey, Hemrich and Amoroso47–Reference Legg50). The availability of these foods is therefore, not only dependent on the production of African foods but controlled by all the elements of the trade and export arrangements in place by the importing HIC and the country where the food is exported from. Hence, any disruption to the international market affects the availability and prices of these traditional foods.

Food environments (food availability and affordability)

Beyond the issues of international trade, the availability and affordability of traditional African foods is largely driven by demand. In areas of super-diversity (refers to the unprecedented collection of different nationalities, faiths, languages, cultures and ethnicities in a society)(Reference Vertovec51), such as in London, Birmingham and Manchester in the UK, traditional African foods are readily available and prices are cheaper compared to areas of less diversity. In these areas of diversity, there are a number of local traditional shops, thus offering competitive prices to attract consumers.

Studies on African migrant origins in Greater Manchester(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell52) and Birmingham(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53) have confirmed that the availability and affordability of traditional foods directly shape eating behaviours of both older and younger African migrants in the UK(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell13,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34,Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53) . In the study conducted in Greater Manchester, participants compared the food environment in the UK with the context before migration, where food was unavailable during certain times of the year and indicated the abundance of foods including traditional foods in the UK(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell52,Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53) . This was attributed not only to the high number of ethnic shops that sold traditional foods in areas of super-diversity, but also because large UK-wide supermarkets such as Tesco, Asda and Sainsburys in super-diverse areas also have aisles stocked with ethnic foods which are described as ‘world foods’ (Table 1). This perception could be because the food environment was compared with that before migration, in which participants reported food scarcity during certain times of the year(Reference Watson and Hiscock54). This could be due to lack of food processing and storage facilities in most farming areas, but also because in many communities food production is dependent on subsistence agriculture and rainfall(Reference Watson and Hiscock54). In a recent scoping review exploring the interactions of factors in the food environment of migrants using the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework, it was found that time constraints, availability of transport services and the opportunity to be sign posted to traditional food markets by close networks were essential overarching themes that influenced the choice of migrants accessing different food options(Reference Berggreen-Clausen, Pha and Alvesson55).

Several studies have also cited how environmental factors change following migration(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9,Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell13,Reference Agyemang, Addo and Bhopal56) . For instance, exposure to a new food supply can result in changes in procuring and preparation of food and the unavailability of traditional foods that can lead to an increased intake of foods found in the host country(Reference Satia-Abouta, Patterson and Neuhouser9).

In more recent times, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of ethnic food shops started trading online and advertising using social media and other ethnic minority-specific communication channels, such as local UK-based African radio stations. These shops offer access to traditional foods even for those living in areas of less diversity. However, the quality and prices of these foods purchased online can differ from foods purchased from physical shops.

Individual level factors

Individual level factors include a person's SES, situational factors(Reference Fanzo, Arabi and Burlingame57), cultural identity, age and ageing, medical condition and body image.

Socio-economic factors

SES is a known driver of dietary behaviours(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Mohindra and Booth10,Reference Roberts, Cavill and Hancock20,Reference Gilbert and Khokhar31,Reference Méjean, Si Hassen and Gojard58) . Populations living in HICs of lower SES based on educational level and/or income tend to have less healthy eating habits compared with populations of higher SES(Reference Roberts, Cavill and Hancock20,Reference Méjean, Si Hassen and Gojard58) . Lower income is shown to restrict food choices, thus compelling the consumption of poorer quality foods(Reference Gilbert and Khokhar31). SES measured by occupation and level of education did not seem to be important in differentiating the different types of dietary practice typologies identified in a recent qualitative study conducted among Ghanaian migrants(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34). In this study, the relatively higher perceived cost of traditional foods did not influence the continued consumption of traditional foods among the bulk of the participants, perhaps because strategies were devised that included substituting certain ingredients to prepare Ghanaian dishes and to maintain the ‘Ghanaian taste’(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34). Similar strategies to maintain traditional foods were also reported in studies conducted among other migrant groups living in Europe(Reference Garnweidner, Terragni and Pettersen35,Reference Škreblin and Sujoldžić59,Reference Lawton, Ahmad and Hanna60) .

Situational factors

Most migrant-origin groups tend to have higher levels of poverty than the majority population(Reference Platt61) and tend to engage in lower paid jobs(Reference Kassam-Khamis, Judd and Thomas62), despite evidence they are often overqualified for these(Reference Herbert, May and Wills63). This impacts the adoption of a healthy lifestyle(Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman11), as stated earlier. For instance, a survey conducted in London among Ghanaian and Nigerian migrants employed in low-paid sectors reported that most respondents in the study engaged in cleaning jobs while others were employed as care workers. Among the participants 94 % earned less than the UK minimum wage in 2008(Reference Herbert, May and Wills63). Also, when using the UK Index of Multiple Deprivation scale, most African migrants live in areas of very high deprivation and often find the prices of their traditional foods in the big chain supermarkets expensive. For instance, a study of older African migrants in Birmingham, UK, found that most women living in the most deprived neighbourhoods according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation scale, described the prices of traditional foods in local supermarkets as slightly more expensive compared with those sold in the budget market located in the city centre(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53). The rapidly rising food and energy prices that have been observed in the UK and other HICs in 2022 are likely to have a disproportionate impact on poorer migrant populations.

Cultural identity

The majority of African migrants still maintain certain dietary behaviours, that is the preparation and consumption of specific traditional foods, as part of their cultural identity or heritage(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53,Reference Chowbey and Harrop64) . This is often particularly true for older generations as compared to younger generations. In a study of older migrants in Birmingham, it was found that the cultural identity associated with consuming their traditional foods was the primary reason for the choice of certain foods rather than their health benefits(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53). Besides the cultural identity of these foods, this study also observed that these foods provided a sense of comfort and feeling of ‘proximity’ to their home country. The importance of cultural identity in maintaining traditional diets was also echoed by younger generation African migrants in a study conducted in Manchester, although they did not attach the same level of importance as the older generation(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34). For the younger generation, having non-Ghanaian social networks and not having enough time to cook Ghanaian foods that were perceived to be time consuming, increased their likelihood of adopting UK dietary practices(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34).

Age and ageing

The physiological, physical and social changes that result from ageing impact significantly dietary behaviours, nutrient needs, nutritional status and sedentary behaviours of older adults(65). Beyond these, other major factors in African migrant communities such as SES status also mediate the entire ageing process through influencing financial access to a nutritious diet. From a physiological perspective, the ageing process impacts the body in many ways that can impair the body's ability to ingest, digest, absorb, process, distribute and store nutrients over time(Reference Morley66). These changes have the tendency to influence the dietary behaviours and nutritional status of older adults(Reference Morley66). Morley and Silver(Reference Morley and Silver67) describe that these age-related changes that can impair dietary behaviour and nutritional status as ‘the anorexia of ageing’. Similar to other ageing populations, the loss of dentition, sight, hearing and taste with age among African migrants are considered to be important drivers of food intake, impacting nutritional status, the prevalence of other diseases and subsequently the quality of life among older adults(Reference Boyce and Shone68–Reference Petersen and Yamamoto70). For example, the loss of teeth with age affects the amount and quality of food consumed. This usually occurs as mealtimes are less pleasurable, which results in the inability to eat a variety of nutritious meals due to chewing difficulties encountered and loss of taste during mealtimes(Reference N'gom and Woda71,Reference Webster-Gandy, Madden and Holdsworth72) . Despite the limited evidence of the impact of these factors among African migrants in the UK, a few studies have found that loss of taste leads to change in dietary behaviours in migrant groups(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Nicolaou and Powell13,Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53) . For example, a group of older African migrants in the UK explained that they were unable to enjoy their African traditional meals as much, due to the loss of taste over time(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53).

From the effect of physical decline with age, there is a considerable amount of literature that demonstrates that the physical ability of an older adult has a direct impact on their nutritional status. For instance, a longitudinal study involving African migrants found that a decline in physical function over time worsened nutrient intakes and nutritional status of ethnic older minorities(Reference Asamane, Greig and Thompson73). A good explanation for this relationship could be the difficulty in shopping and preparing food, especially traditional meals, due to physical limitations, which could eventually lead to inadequate dietary intake and malnutrition.

Medical condition and body image

In the UK, some African migrants have made substantive changes to their eating behaviours for medical reasons, such as changing diet, altering their eating patterns, reducing portion sizes or cooking methods to manage current health condition. In a qualitative study in Birmingham, the fear of losing independence and other accompanying complications from diabetes and other NR-NCDs emerged as motivating factors for some African migrants to eat healthily and maintain their physical function(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53). However, it is worth stating that African migrants who made changes to their diets also reported attending relevant health education sessions(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53).

Similar to medical conditions, body image perception remains a strong driver of certain meal preferences among African migrants in the UK(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53,Reference Castaneda-Gameros, Redwood and Thompson74) . This is mostly the case with female African migrants as compared to males. In Birmingham, a longitudinal study of ethnic minorities found that more females reported reducing porting sizes or abandoning certain traditional foods to keep a healthy and ‘desirable’ weight to help them maintain good health or manage existing health conditions(Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53).

Consumer behaviours

Consumer behaviours in this context refers to food-related decisions or choices that African migrants make regarding what foods to buy, where to buy, how to prepare and consume food and how to store it. Taste, socio-cultural context, age and medical conditions (as discussed earlier) have been found to strongly influence consumer behaviours of African migrants in the UK(Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou34,Reference Asamane, Greig and Aunger53) .

Policies actions on non-communicable diseases in England and relevance to migrant populations

At a UN general assembly meeting held a decade ago on NCDs, world leaders pledged their full commitment to tackle the NCD burden(Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Alleyne75). Subsequently the World Health Assembly set out global targets, key among these was an action to reduce mortality from four NCDs (CVDs, cancers, type 2 diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases), and halt the rise in diabetes and obesity(Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Horton76). This commitment required that countries develop and implement policy actions and show political will towards their realisation. While many countries now have NCD policies, and some are making significant progress in terms of implementation to tackle the problem, others appear to have made little to no progress in policy development and implementation, especially some low- and middle-income countries(77).

In England, the government has taken important policy actions, in line with its commitment, to tackle the obesity crisis. Key policy initiatives include the sugar reduction policy(78) to tackle childhood obesity, which aims to promote healthy eating and physical activity in primary schools(79), and more recently the launch of the policy to tackle obesity more generally, which includes a campaign for ‘better health’(80) (Table 2). Although these policies are expected to contribute to tackling the obesity crisis (as a risk factor of many of the NCDS), a recent review(Reference Theis and White81) examining the nature and strategic adequacy of these policies, concluded that obesity policies in England have largely been proposed in a way that does not facilitate implementation, document impact or learn from policy failures, and that the government has often tended to adopt less interventionist policy approaches, i.e. policy interventions that allow individuals to take control and make behaviour changes to reduce NCDs, rather than address the external environment factors that contributes to it, hence making them less effective. Table 2 presents a summary of the current government policies/initiatives to address obesity in England and identifies how no or superficial attention has been given to migrant population groups in these.

Table 2. List of the current government strategies (2016–2022) in England(Reference Raleigh and Holmes82)

Although the UK government recognises the need to address health inequalities in England, and some of the obesity strategies in Table 2 have specifically mentioned this with key targets aiming to reduce inequalities in NCDs in the population. However, there is great concern that these policies are not inclusive or do not explicitly consider the health needs of migrant or ethnic minority groups in general, which then cast doubt on the potential impact of the policies to achieve impact. Only the recently introduced policy (the tackling obesity: government strategy, 2020) superficially highlighted the need to tackle the health disparities between ethnic minority groups and the majority white population, but no specific actions are outlined in the policy to prioritise this group. The lack of emphasis on migrant health contributes to explaining why health inequality gaps in England continue to widen evidence in health and disease patterns that continue to differ significantly between ethnic minority and migrant groups compared with the majority white population, and between the different ethnic minority and migrant groups(Reference Raleigh and Holmes82). Migrants living in England suffer the most from different NCDs, and this is reflected in the COVID-19 mortality data too, which shows that ethnic minority groups were disproportionately affected(83). For the government policies and interventions to achieve any impact in addressing health inequalities or tackle NCDs they need to be inclusive, both during their development and implementation, and take into consideration the diversity of migrant groups living in England, in terms of their culture, demographic, socio-economic backgrounds, as well as the beliefs they hold, as these impact significantly on health seeking behaviours and practices.

Implications for policy and research

Interventions that focus primarily on individual level drivers of dietary behaviours have limited success when they do not consider the wider food environment and factors in the food system. The present paper supports the need for deep structure sensitivity in interventions, which means understanding the cultural, social, environmental, psychological and historical forces that influence dietary practices within migrant populations, before designing interventions(Reference Hawkes and Ruel46). This is particularly important, given that migrant studies often define ethnicity in broad categories and assume homogeneity in the characteristics of large ethnic minority groups(Reference Lartey, Hemrich and Amoroso47). Dietary practices of African migrants are not homogenous and there is the need to recognise this, while considering the other wider range of factors influencing diet.

Current routine data collected in most European countries do not provide insight into dietary practices of migrant groups. Such data, if available can inform policies for nutrition interventions applicable or specific to migrant groups. Considerable variations in dietary behaviours across and within different ethnic groups(Reference Hawkes and Ruel48) limit the extent to which research tools that are used in HICs can be used, as these are usually developed for the host population and may not be suitable for migrant groups(Reference Grace49). However, including routine data from migrant groups can result in the addition of new foods to update food consumption assessment tools (such as food frequency questionnaires) and food composition data in order to capture all available foods in Europe, thus bridging this gap in knowledge related to the dietary behaviours of migrant groups(Reference Legg50). An opportunity for research is to explore the relative importance of various factors identified and their associations with dietary behaviours and the subsequent impact on NR-NCDs.

The present paper addresses some of the gaps in knowledge regarding dietary change and the food environment and the socio-economic context following migration. It also summarises the evidence, which shows that dietary change among people of African migrants living in Europe is a complex nonlinear process, dependent on several interrelated factors in food environments both before and after migration, which is often mediated by SES.

Financial Support

H. O.-K. was an AXA postgraduate researcher at the University of Sheffield, Department of Geography. She was supported by AXA research fund.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

H. O.-K., D. B. and M. H. conceptualised the paper. All authors had joint responsibility for all aspects of preparation of this paper.