CVD are the leading cause of mortality globally, accounting for about 31 % of deaths each year( 1 ). In the UK, CVD was the second most common cause of death in 2014, responsible for 27 % of all mortalities( Reference Townsend, Bhatnagar and Wilkins 2 ). There are several recognised risk factors for CVD, including raised serum LDL-cholesterol and TAG, low serum HDL-cholesterol, elevated blood pressure (BP), diabetes and obesity many of which can be modified by lifestyle choices, including diet( Reference Lewington, Whitlock and Clarke 3 ). Epidemiological data from the 1970s indicated that CHD rates were higher in countries with low fruit and vegetable consumption( Reference Ness and Powles 4 ). This has been supported by a number of more recent studies that have shown that dietary patterns rich in fruit and vegetables are associated with reduced rates of CHD, stroke and CVD mortality( Reference Joshipura, Hu and Manson 5 – Reference Joshipura, Ascherio and Manson 10 ). Some researchers have attempted to identify the types of fruit and vegetables responsible for the reduced risk of CVD. Joshipura et al.( Reference Joshipura, Hu and Manson 5 ) showed that people in the highest quintile of fruit and vegetable intake had a 20 % lower relative risk (RR) for CHD compared with those in the lowest quintile of intake. In addition, each one serving per day increase in fruit and vegetable intake was associated with a 4 % lower risk of CHD. They also found that vitamin C-rich fruits (6 % lower RR per one serving per day increase) and particularly green leafy vegetables (23 % lower RR per one serving per day increase) had the largest protective effects( Reference Joshipura, Hu and Manson 5 ).

Fruit and vegetables are a rich source of phytochemicals such as flavonoids and dietary nitrates, which have been shown to independently exert a number of health effects and could be responsible, at least in part, for the apparent protective effects of fruit and vegetable consumption. The aim of this review is to provide a brief overview of evidence related to the effects of flavonoids and dietary nitrates on cardiovascular health with particular reference to vascular and platelet function.

Dietary flavonoids

The main categories of phytochemicals are polyphenols, which include flavonoids, terpenoids, nitrogen-containing alkaloids and sulphur-containing compounds. Flavonoids are produced by plants as secondary metabolites and have biological roles in plant pigmentation, flavour, growth, reproduction, predator and pathogen resistance( Reference Bravo 11 ). They are present in a variety of foods, including vegetables, fruit, nuts, grains, red wine and chocolate, in concentrations that vary due to a number of factors, including environmental stress, such as UV exposure( Reference Ordidge, Garcia-Macias and Battey 12 ). Flavonoids consist of two benzene rings linked by a three-carbon chain (C6–C3–C6) as shown in Fig. 1. The flavonoid classes differ due to the C ring structural differences, number of phenolic hydroxyl groups and their substitutions, and are commonly divided into seven structural subclasses namely: isoflavones, flavanols or catechins, flavanonols, flavonols, flavanones, flavones, anthocyanins and anthocyanidins( Reference Leonarduzzi, Testa and Sottero 13 ) (Fig. 2). The small structural variations between subclasses are related to considerable differences in biological functions.

Fig. 1. Generic structure of a flavonoid consisting of two benzene rings linked by a 3-carbon chain.

Fig. 2. Structure of the seven classes of flavonoids shown as aglycones.

Absorption and metabolism of flavonoids

Flavonoids are commonly found in the diet as conjugated esters, glycosides or polymers, which have limited bioavailability, requiring intestinal enzyme hydrolysis or colonic microbiota fermentation before absorption into the circulation. Aglycones formed in the intestine by cleavage of flavonoid side chains can enter the epithelial cell by passive diffusion( Reference Day, Canada and Diaz 14 ). However, polar glucosides can be actively transported into epithelial cells via the sodium-GLUT1, where they are hydrolysed by intracellular enzymes to the aglycone( Reference Day, Mellon and Barron 15 ). The importance of the latter absorption route is unclear, but glycosylated flavonoids and aglycones have been shown to inhibit the sodium-GLUT1, potentially reducing dietary glucose absorption( Reference Johnston, Clifford and Morgan 16 ). Before transport to the circulation, the aglycones also undergo further metabolism (phase II) and conjugation, including glucuronidation, methylation or sulphation. Efflux of the metabolites back into the intestine also occurs via transporters, including multidrug resistance protein and P-glycoprotein and the GLUT2( Reference Manzano and Williamson 17 ). Further phase II metabolism occurs in the liver via portal vein transportation and further recycling into the intestinal lumen via the enterohepatic recirculation in bile( Reference Donovan, Crespy and Manach 18 ). Some flavonoids, particularly polyphenol sugar conjugates, pass unabsorbed into the colon and are associated with marked modulation of the colonic gut microbiota( Reference Klinder, Shen and Heppel 19 ) and the production of principally small phenolic acid and aromatic catabolites, which are subsequently absorbed into the circulation( Reference Koutsos, Tuohy and Lovegrove 20 ). These metabolites can be subjected to further metabolism in the liver before they are efficiently excreted in the urine in quantities far higher than those that entered the circulation via the intestine( Reference Jaganath, Mullen and Edwards 21 ). Due to the extensive metabolism and rapid excretion, plasma concentrations do not reflect quantitative absorption and total urinary metabolite excretion can be a more valuable biomarker of intake. Evidence for tissue accumulation of polyphenols and their metabolites is very limited and while this cannot be ruled out, it is believed that frequent ingestion of flavonoid-rich foods is required to maintain constant circulating levels (see review( Reference Del Rio, Rodriguez-Mateos and Spencer 22 )). Detailed studies using stable isotopes have allowed the determination of metabolic pathways of certain polyphenol subclasses. Anthocyanins, found in foods such as berries, are reported to have low bioavailability, but recent data have shown they are extensively metabolised to a diverse range of metabolites, which has highlighted a previous underestimation of anthocyanin absorption and metabolism( Reference de Ferrars, Czank and Zhang 23 ).

Flavonoid intake and CVD risk: epidemiological studies

Epidemiological studies have produced strong evidence for the negative association between high fruit and vegetable consumption and CVD mortality( Reference Dauchet, Amouyel and Dallongeville 24 , Reference Hu and Willett 25 ). However, it is difficult to identify the specific mediator(s) of health due to the numerous potential bioactive compounds present in fruit and vegetables. Observational studies suggest that intakes of flavonoids are associated with a decreased risk of CVD, although the findings are not entirely consistent, because of variation in population studied, dose and specific flavonoid consumed. Data from a large post-menopausal cohort identified a negative association between flavonoid-rich diets and CVD mortality( Reference Mink, Scrafford and Barraj 26 ). Further evidence showed intakes of flavanol- and procyanidin-rich foods were associated with decreased risk of chronic non-communicable diseases particularly CVD( Reference Desch, Kobler and Schmidt 27 , Reference Heiss, Keen and Kelm 28 ). In 2005, Arts and Hollman collated data from fifteen prospective cohort studies; of these thirteen provided evidence for a positive association between dietary flavanols, procyanidins, flavones and flavanones and CVD health, with a reduction of CVD mortality of approximately 65 %( Reference Arts and Hollman 29 ). Systematic reviews( Reference Wang, Nie and Zhou 30 – Reference Hollman, Geelen and Kromhout 32 ) that have focused on flavonol intake have reported inconsistent findings, including an inverse association between high flavonol intake and CHD or stroke mortality( Reference Huxley and Neil 31 , Reference Hollman, Geelen and Kromhout 32 ) compared with no association between flavonol intake and CHD risk( Reference Wang, Nie and Zhou 30 ). However, a more recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of fourteen studies identified that intakes of anthocyanidins, proanthocyanidins, flavones, flavanones and flavan-3-ols were associated with lower CVD; RR of 11, 10, 12, 12 and 13 %, respectively, when comparing the highest and lowest categories of intake; with a 5 % lower RR for CVD for every 10 mg/d increment in flavonol intake( Reference Wang, Ouyang and Liu 33 ).

An inverse association between flavanol intake and CVD mortality was initially identified in the Iowa women health study, which followed 34 489 women, free of CVD at study inclusion( Reference Arts, Jacobs and Harnack 34 ) while, a subsequent follow-up found no association between reduced CVD risk and flavanol intake, instead an association with procyanidin intake( Reference Mink, Scrafford and Barraj 26 ). These seemingly contrasting findings were due to the different ways the data from chocolate and seeded grapes were categorised in the dietary assessment, and emphasise the importance of standardisation of dietary assessment, and the possible benefits of using biomarkers of intake. Evidence from prospective cohort studies generally supports the hypothesis that a greater intake of dietary flavonoids is associated with a lower risk of CVD, although there are inconsistencies in potential benefit. Further supportive evidence from well-performed randomly controlled dietary intervention studies is required to establish a direct relationship between different flavonoid sub-groups and CVD risk.

Chronic and acute effects of flavonoid intake on micro- and macrovascular function

The vascular endothelium plays a key role in the regulation of vascular homeostasis, and alterations in endothelial function contribute to the pathogenesis and clinical expression of CVD( Reference Vita and Keaney 35 ). Many factors impact adversely on the endothelium; these include diabetes mellitus, smoking, physical inactivity, ageing, hypertension, systemic inflammation, dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance, with diet being key in modulating endothelial function( Reference Fung, McCullough and Newby 36 , Reference Meigs, Hu and Rifai 37 ). Prospective cohort studies have supported the association between endothelial function and an increased risk of CVD events and have identified the latter as a valuable holistic surrogate marker of CVD risk( Reference Halcox, Donald and Ellins 38 , Reference Vita 39 ). Endothelial dysfunction has been associated with the development of atherosclerosis and CVD( Reference Drexler and Hornig 40 ) and is most commonly measured in the brachial artery by flow-mediated dilatation (FMD), which uses non-invasive ultrasound before and after increasing shear stress by reactive hyperaemia, with the degree of dilation reflecting arterial nitric oxide (NO) release. Another commonly used technique is laser Doppler imaging with iontophoresis, which measures the endothelial function of the peripheral microcirculation. The degree of endothelial dysfunction occurring in the microcirculation has been shown to be proportional to that occurring in the coronary arteries( Reference Stehouwer 41 ). This technique measures the response of cutaneous blood vessels to transdermal delivery of two contrasting vasoactive agents: acetylcholine (endothelium-dependent vasodilator) and sodium nitroprusside (endothelium-independent vasodilator) by iontophoresis. A reduced local vasodilatory response to acetylcholine is associated with endothelial dysfunction( Reference Ramsay, Ferrell and Greer 42 ).

Consumption of fruit rich in anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in the form of purple grape juice or grape seed extract (for between 14 and 28 d) significantly increased FMD in volunteers with angiographically documented CHD or above average vascular risk( Reference Chong, Macdonald and Lovegrove 43 ). Furthermore, consumption of pomegranate, containing tannins and anthocyanins, for a period of 90 d to 3 years resulted in improvements in carotid intermedia thickness, a measure of the extent of atherosclerosis in the carotid artery, in those with increased CVD risk( Reference Chong, Macdonald and Lovegrove 43 ). The FLAVURS study investigated the dose-dependent effect (+2, +4 and +6 additional portions/d) of flavonoid-rich and flavonoid-poor fruit and vegetables compared with habitual diet, on microvascular reactivity, determined by laser Doppler imaging with iontophoresis and other CVD risk markers. After two additional portions of flavonoid-rich fruit and vegetables, equivalent to an estimated increase in total dietary flavonoids from 36 (sem 5) to 140 (sem 14) mg/d( Reference Chong, George and Alimbetov 44 ), a significant increase in endothelium-dependent microvascular reactivity was observed in men. In addition, reduced C-reactive protein, E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule and increased plasma NOx was observed with four additional flavonoid-rich portions, compared with the control and low-flavonoid intervention( Reference Macready, George and Chong 45 ). These data support vascular improvements reported in a previous study investigating a similar single dose of flavonoid-rich foods( Reference Dohadwala, Holbrook and Hamburg 46 ). Identification of the specific flavonoid bioactive is not possible in studies that include a variety of foods, yet these data demonstrate that dietary relevant doses of total flavonoids can contribute to vascular health and could be considered as useful strategies for CVD risk factor reduction.

The majority of the population is in a postprandial state for most of the day and it is recognised that acute physiological responses to meals are a major contributor to overall CVD risk. Flavonoid-rich foods have been implicated in modulating postprandial responses. For example, blueberries are a rich source of flavonoids, particularly anthocyanin, flavanol oligomer and chlorogenic acid( Reference Rodriguez-Mateos, Del Pino-Garcia and George 47 ). Acute improvements in vascular function, measured by FMD, were observed in healthy men in a time- and dose-dependent manner (up to a concentration of 766 mg total polyphenols)( Reference Rodriguez-Mateos, Rendeiro and Bergillos-Meca 48 ) with little observed effect of processing( Reference Rodriguez-Mateos, Del Pino-Garcia and George 47 ). These beneficial effects on postprandial vascular reactivity are not confined to blueberries, as a mixed fruit puree containing, 457 mg (-)-epicatechin increased microvascular reactivity and plasma NOx ( Reference George, Waroonphan and Niwat 49 ). Although the fruit puree contained varied flavonoids, the potential vascular benefits of (-)-epicatechin are supported by a meta-analysis of six randomly controlled trials, which found that 70–177 mg (-)-epicatechin, from cocoa or chocolate sources significantly increased postprandial FMD by 3·99 % at 90–149 min post-ingestion( Reference Hooper, Kay and Abdelhamid 50 ). These data indicate that different classes of flavonoids in the form of foods can significantly improve postprandial vascular function and possible CVD risk.

Flavanols, as a subgroup of flavonoids, have been extensively studied and increasing evidence has shown that higher intake of flavanol-rich foods improve arterial function in numerous groups including those at risk for CVD, with established CVD( Reference Heiss, Dejam and Kleinbongard 51 ) and more recently healthy young and ageing individuals( Reference Sansone, Rodriguez-Mateos and Heuel 52 ). The mechanisms of action are not totally understood, but causality between intake and an improvement in arterial function has been demonstrated( Reference Schroeter, Heiss and Balzer 53 ). The important dietary flavonol, (-)-epicatechin, is naturally present is high concentrations in cocoa, apples and tea and a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, including a recent study of forty-two randomised controlled human dietary intervention studies on supplemental and flavan-3-ols-rich chocolate and cocoa, reported significant acute and chronic (up to 18 weeks) dose-dependent cardiovascular benefits, including recovery of endothelial function, lowering of BP and some improvements in insulin sensitivity and serum lipids( Reference Hooper, Kay and Abdelhamid 50 , Reference Ried, Sullivan and Fakler 54 , Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm 55 ). Furthermore green and black tea (rich in (-)-epicatechin) was also reported to reduce BP and LDL-cholesterol in a systematic review and meta-analysis of a small number of studies, but these findings need confirmation in long-term trials, with low risk of bias( Reference Hartley, Flowers and Holmes 56 ). The extensive studies into the vascular effects of (-)-epicatechin and their impact on other CVD risk markers has prompted some to propose specific dietary recommendation for these flanonoids and a broader recommendation on flavanol-rich fruit and vegetables for CVD risk reduction, although further evidence may be required before specific recommendations are considered.( Reference Schroeter, Heiss and Spencer 57 )

Possible mechanisms of flavonoids and vascular effects

Despite the high antioxidant potential of a number of classes of flavonoids, there is limited evidence to support this mechanism of action due to the low plasma concentrations of flavonoids compared with other endogenous or exogenous antioxidants( Reference Hollman, Cassidy and Comte 58 ). Many of the vascular effects of flavonoids have been associated with molecular signalling cascades and related regulation of cellular function. One of the potential mechanisms of action is the association between flavonoid, particularly (-)-epicatechin, and prolonged, augmented NO synthesis, the primary modulator of vascular dilation( Reference Schroeter, Heiss and Balzer 53 ). NO production from L-arginine is regulated by three NO synthase (NOS) enzymes: endothelial NOS (eNOS), neuronal NOS and inducible NOS with lower production and/or availability of NO as the main effect on endothelial dysfunction. Several in vitro and human studies have reported potent vasorelaxant activity of certain flavonoids related to activation of eNOS( Reference Schroeter, Heiss and Balzer 53 , Reference Almeida Rezende, Pereira and Cortes 59 ). A common polymorphism in the eNOS gene is the Glu298Asp SNP that modifies its coding sequence, replacing a glutamate residue at position 298 with an aspartate residue. This polymorphism has been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events putatively through reduced NO production by eNOS( Reference Hingorani, Liang and Fatibene 60 , Reference Tian, Zeng and Wang 61 ). Interestingly, in a small acute randomised control study a significant genotype interaction with endothelium-dependent microvascular dilation was observed after consumption of fruit and vegetable puree containing 456 mg (-)-epicatichin. Wild-type, GG, participants (non-risk group) showed an increased endothelial vasodilation at 180 min compared with control, with no effect in T allele carriers. This supports the importance of (-)-epicatichin in eNOS activation and NO availability, with little vascular effect of (-)-epicatichin in those with impaired eNOS function. This nutrient–gene interaction may explain in part, the large variation in individual vascular responses to flavonoid consumption, but requires further confirmatory studies( Reference George, Waroonphan and Niwat 62 ).

Flavonoids have also been reported to modulate xanthine oxidase activity, resulting in decreased oxidative injury and consequential increased NO( Reference Cos, Ying and Calomme 63 ). The vascular effects induced by phenolics may also be mediated by the inhibition of Ca2+ channels and/or the blockage of the protein kinase C-mediated contractile mechanism, as has been observed for caffeic acid phenyl ester and sodium ferulate, respectively( Reference Chen, Ye and Li 64 ). Furthermore, benefits may be mechanistically linked to the actions of circulating phenolic metabolites on inhibition of neutrophil nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity, which prevents NO degradation and increases its availability( Reference Rodriguez-Mateos, Rendeiro and Bergillos-Meca 48 ). More recently a possible role of flavonoid promotion of endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor in vasodilation, which induces hyperpolarisation, thus leading to dilation of the vascular smooth muscle cell has been identified( Reference Ndiaye, Chataigneau and Chataigneau 65 ). In summary, there are multiple potential mechanisms by which flavonoids and their metabolites can modulate vascular function( Reference Mladenka, Zatloukalova and Filipsky 66 ) and these may act in an additive or synergistic manner. It is evident that dietary relevant doses of flavonoids are associated with vascular benefit with varied proposed modulating mechanisms that require elucidation in further studies.

Flavonoids and platelet aggregation

Platelets are small nucleated cell fragments that are produced by megakaryocytes in the bone marrow( Reference Italiano, Lecine and Shivdasani 67 , Reference Patel, Hartwig and Italiano 68 ) and play a critical role in haemostasis through formation of aggregates over arterial wall injuries( Reference Ruggeri 69 ). When platelet activation becomes impaired, thrombosis can occur, a pathophysiological condition, which can lead to blockage of coronary arteries or impaired blood supply to the brain, leading to events such as myocardial infarction or stroke( Reference Gibbins 70 ). Many studies have previously shown the ability of flavonoids to inhibit platelet function( Reference Guerrero, Lozano and Castillo 71 – Reference Gadi, Bnouham and Aziz 73 ). Quercetin is found in many foods such as apples, onions, tea and wine, and present in significant quantities in many diets( Reference Hertog, Hollman and Katan 74 ). Further understanding of how quercetin modulates platelet function is of relevance to establish a mechanistic link between flavonols and CVD risk.

Hubbard et al.( Reference Hubbard, Wolffram and Lovegrove 75 ) observed a significant inhibition of ex vivo platelet aggregation after ingestion of quercetin-4′-O-β-D-glucoside at a dose of 150 mg and 300 mg, with peak quercetin metabolite concentrations of 4·66 µm and 9·72 µm, respectively. These data were supported by a further small human study, which reported peak plasma quercetin metabolite concentrations of 2·59 µm and significant inhibition of ex vivo collagen-stimulated platelet aggregation 60 and 240 min after consumption of a high-quercetin onion soup rich in quercetin glucosides (68·8 mg total quercetin) compared with a matched low quercetin onion control (4·1 mg total quercetin)( Reference Hubbard, Wolffram and de Vos 76 ). Inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase and phospholipase Cγ2, two key platelet proteins involved with the collagen-stimulated signalling pathway were also observed, and confirms this as one potential mechanism of action. These data are in agreement with previous in vitro studies displaying the ability of quercetin to inhibit collagen, ADP and thrombin-stimulated platelet aggregation, as well as inhibiting collagen-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinases and phosphoinositide 3-kinase phosphorylation( Reference Oh, Endale and Park 77 , Reference Hubbard, Stevens and Cicmil 78 ).

Flavonoids undergo significant endogenous metabolism and it is important to determine the bioactivity of metabolites as well as the aglycones by understanding structure–activity relationships and how functional groups affect platelet function. Anti-platelet effects of tamarixetin, quercetin-3-sulphate and quercetin-3-glucuronide, as well as the structurally distinct flavonoids apigenin and catechin, quercetin and its plasma metabolites were determined. Quercetin and apigenin significantly inhibited collagen-stimulated platelet aggregation and 5-hydroxytryptamine secretion with similar potency, and logIC50 values for inhibition of aggregation of −5·17 (sem 0·04) and −5·31 (sem 0·04), respectively( Reference Wright, Moraes and Kemp 79 ). Flavones (such as apigenin) are characterised by a non-hydroxylated C-ring, whereas the C-ring of flavonols (e.g. quercetin) contain a C-3 hydroxyl group (Fig. 1). Catechin was less effective, with an inhibitory potency two orders of magnitude lower than quercetin, suggesting that in vivo, metabolites of quercetin and apigenin may be more relevant in the inhibition of platelet function. Flavan-3-ols such as catechin possess a non-planar, C-3 hydroxylated C ring, which is not substituted with a C-4 carbonyl group (as is found in flavonols). Quercetin-3-sulphate and tamarixetin (a methylated quercetin metabolite) were less potent than quercetin, with a reduction from high to moderate potency upon addition of a C-4′ methyl or C-3′-sulphate group, but at concentrations above 20 µm, all achieved substantial inhibition of platelet aggregation and 5-hydroxytryptamine release. Quercetin-3-glucuronide caused much lower levels of inhibition, providing evidence for reduced potency upon glucuronidation of the C ring. Jasuja et al. have shown quercetin-3-glucuronide to potently inhibit protein disulphide isomerase, an oxidoreductase important in thrombus formation( Reference Jasuja, Passam and Kennedy 80 ). X-ray crystallographic analyses of flavonoid-kinase complexes have shown that flavonoid ring systems and the hydroxyl groups are important features for kinase binding( Reference Lu, Chang and Baratte 81 , Reference Wright, Watson and McGuffin 82 ) supporting the evidence for structure-specific effects on platelet function. Taken together, this evidence shows the importance of understanding the structural differences of flavonoids, and how specific functional groups on polyphenols can lead to enhanced or reduced effects in different stages of haemostasis and thrombosis. This evidence may also facilitate the design of small-molecular inhibitors and inform specific dietary advice.

In summary, flavonoids are generally poorly absorbed and substantially metabolised to aid rapid elimination. Many flavonoid subgroups reach the colon in their native state, and are fermented by the microbiota, which produces small phenolic metabolites with potential bioactivity after absorption. CVD risk reduction from high fruit and vegetable intake may be due, in part, to benefits from flavonoid ingestion. In particular, (-)-epicatechin, a key flavanol, has been causally linked with increased arterial endothelial-dependent dilation measured by FMD, with a putative increase in NO bioavailability. Other potential mechanisms of action include modulation of NADPH oxidase activity and reduction of NO degradation. Furthermore, flavonoids, particularly quercetin and its metabolites, reduce in vitro and ex vivo platelet function, possibly via inhibiting phosphorylation in cell signalling cascades. Further research will be required to determine the biological effects of flavonoid subgroups in vivo, and the minimal effective dose of these compounds before it is possible to make any specific dietary recommendations.

Inorganic nitrate and nitrite

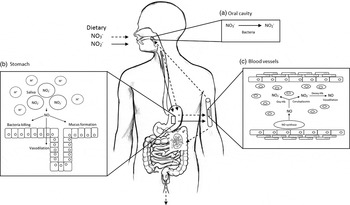

Inorganic nitrate and nitrite were previously considered largely inactive by products of the oxidation of NO endogenously. However, emerging evidence suggest these anions are important storage forms of NO, which can be reduced to bioactive NO under certain conditions. Nitrate is particularly abundant in vegetables such as beetroot and green leafy varieties (spinach, lettuce and rocket) where it is absorbed from the soil and transported to the leaf where it accumulates. Nitrate is important for plant function and is the main growth-limiting factor. In UK diets, estimates from 1997 suggest that the average nitrate intake is approximately 52 mg/d, with vegetables being the main source of nitrate, contributing about 70 % of daily intakes with the remaining nitrate derived from drinking-water( Reference Ysart, Miller and Barrett 83 ) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Diagram of inorganic nitrate metabolism via the nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide (NO) pathway (adapted from Hobbs et al.( Reference Hobbs, George and Lovegrove 115 )). A proportion of ingested nitrate (NO3 −, - - -▸) is converted directly to nitrite (NO2 −, →) by facultative anaerobic bacteria, that reside in plaque and on the dorsum of the tongue, during mastication in the mouth (a); the remainder is swallowed and is rapidly absorbed from the upper gastrointestinal tract. Approximately 25 % is removed from the circulation and concentrated in the salivary glands and re-secreted into the mouth, where it is reduced to nitrite. Some of the salivary nitrite enters the acidic environment of the stomach once swallowed (b), where NO is produced non-enzymically from nitrite after formation of nitrous acid (HNO2) and then NO and other nitrogen oxides. The NO generated kills pathogenic bacteria and stimulates mucosal blood flow and mucus generation. The remaining nitrite is absorbed into the circulation; in blood vessels (c) nitrite forms vasodilatory NO after a reaction with deoxygenated Hb (deoxy-Hb). Approximately 60 % of ingested nitrate is excreted in urine within 48 h. Oxy-Hb, oxygenated Hb.

The consumption of inorganic nitrate either from dietary or supplemental sources have been shown to exert a number of important vascular effects such as BP lowering, protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury, inhibiting platelet aggregation, preserving or improving endothelial dysfunction and enhancing exercise performance( Reference Omar, Webb and Lundberg 84 ).

The nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway

The continuous generation of NO from L-arginine by the enzymatic action of eNOS in the presence of oxygen within endothelial cells is important for maintenance of vascular homeostasis. Indeed reduced production or bioavailability of NO is associated with a number of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders( Reference Cannon 85 ). The nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway is a NOS and oxygen independent pathway for the generation of bioactive NO, and is an important alternative pathway for NO production, particularly during periods of hypoxia( Reference Lundberg, Weitzberg and Cole 86 ). Ingested nitrate, obtained mainly from green leafy vegetables and beetroot, is readily absorbed in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract where it mixes with NO produced from NOS( Reference Wagner, Schultz and Deen 87 ).

Circulating concentrations of ingested nitrate peak after approximately 1 h( Reference Webb, Patel and Loukogeorgakis 88 ) and remains elevated for up to 5–6 h post-ingestion. The majority of ingested nitrate (65–75 %) is excreted in urine with a very small proportion of nitrate (<1 %) reaching the large bowl, which is excreted in the faeces( Reference Bartholomew and Hill 89 ). The remaining nitrate is reabsorbed by the salivary glands and concentrated up to 20-fold, reaching concentrations of 10 mm in the saliva( Reference Lundberg and Govoni 90 ). Salivary nitrate is converted to nitrite via a two-electron reduction, a reaction that mammalian cells are unable to perform, during anaerobic respiration by nitrate reductases produced by facultative and obligate anaerobic commensal oral bacteria( Reference Lundberg, Weitzberg and Cole 86 , Reference Duncan, Dougall and Johnston 91 ). The importance of oral bacteria in the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway has been demonstrated in a number of studies( Reference Webb, Patel and Loukogeorgakis 88 , Reference Petersson, Carlstrom and Schreiber 92 , Reference Kapil, Haydar and Pearl 93 ). When the nitrite rich saliva reaches the acidic environment of the stomach some of it reacts to form nitrous acid, which further decomposes to NO and other reactive nitrogen oxides( Reference Benjamin, O'Driscoll and Dougall 94 ). The remaining nitrite (approximately 95 %) is absorbed into the circulation( Reference Hunault, van Velzen and Sips 95 ) where it forms NO via the action of a number of different nitrite reductases, which have selective activity under oxygen/hypoxic/ischaemic conditions. These include Hb( Reference Cosby, Partovi and Crawford 96 ), myoglobin( Reference Shiva, Huang and Grubina 97 ), cytoglobin and neuroglobin( Reference Petersen, Dewilde and Fago 98 ), xanthine oxidoreductase( Reference Webb, Milsom and Rathod 99 ), aldehyde oxidase( Reference Li, Cui and Kundu 100 ), aldehyde dehydrogenase type 2( Reference Badejo, Hodnette and Dhaliwal 101 ), eNOS( Reference Webb, Milsom and Rathod 99 ), cytochrome P450( Reference Li, Liu and Cui 102 ) and the mitochondrial electron transport chain( Reference Nohl, Staniek and Sobhian 103 ). It is likely that the majority of the cardioprotective effects observed from dietary nitrate consumption are via the conversion of nitrite to NO in blood and tissues.

Vascular effects of dietary nitrate and nitrite

Beneficial effects of nitrate consumption on vascular related function were first identified by Larsen et al.( Reference Larsen, Ekblom and Sahlin 104 ), who showed that supplementation of healthy human subjects for 3 d with sodium nitrate reduced BP. Since then, a number of studies have shown that dietary nitrate-rich vegetable sources such as beetroot juice, spinach, rocket and breads also lower BP and vascular function in healthy subjects( Reference Webb, Patel and Loukogeorgakis 88 , Reference Hobbs, Goulding and Nguyen 105 – Reference Jonvik, Nyakayiru and Pinckaers 107 ).

Endothelial dysfunction

A hallmark of endothelial dysfunction is the reduced bioavailability of NO, either through reduced eNOS activity or expression, or via increased NO consumption by free radicals and reactive oxygen species( Reference Vanhoutte 108 ) as discussed earlier. It has been shown that consumption of 500 ml beetroot juice containing 23 mm nitrate reversed the deleterious effects of a mild ischaemia-reperfusion injury to the forearms of healthy subjects and preserved the FMD response, whereas the response was reduced by 60 % in the control subjects( Reference Webb, Patel and Loukogeorgakis 88 , Reference Kapil, Haydar and Pearl 93 ). Hobbs et al.( Reference Hobbs, Goulding and Nguyen 105 ) found that consumption of bread enriched with beetroot increased endothelium-independent blood flow in healthy subjects measured by laser Doppler imaging with iontophoresis. In healthy overweight and slightly obese subjects consumption of 140 ml beetroot juice (500 mg nitrate) or control alongside a mixed meal (57 g fat) attenuated postprandial impairment of FMD( Reference Joris and Mensink 109 ). More recently, daily consumption of dietary nitrate in the form of beetroot juice over a 6-week period resulted in a 1·1 % increase in the FMD response compared with a 0·3 % worsening in the control group( Reference Velmurugan, Gan and Rathod 110 ). However, not all studies have found a beneficial effect of dietary nitrate on endothelial function, with no effects of 250 ml beetroot juice (7·5 mm nitrate) on FMD response in patients with type 2 diabetes( Reference Gilchrist, Winyard and Aizawa 111 ). Furthermore, supplemental potassium nitrate consumption (8 mm nitrate) did not affect FMD response in healthy subjects, although a significant reduction (0·3 m/s) in pulse wave velocity and systolic BP (4 mmHg) at 3 h compared with the potassium chloride control was reported. This suggests that although inorganic nitrate did not alter endothelial function, it did appear to increase blood flow in combination with reductions in BP.

Organic and inorganic nitrate/nitrites are both effective in vascular health, yet it has been proposed that inorganic dietary nitrate may be a more appropriate choice for vascular modulation than organic nitrate supplements( Reference Omar, Artime and Webb 112 ). The enterosalivary circulation is key for the effects of inorganic nitrate and prevents a sudden effect, or toxic circulating concentrations of nitrite, in addition to prolonging the vascular effects. In contrast, supplemental organic nitrate, which does not require the enterosalivary circulation for absorption, has rapid pharmacodynamic responses, causing potent acute effects, immediate vasodilation and in chronic use considerably limited by the development of tolerance and endothelial dysfunction. The more subtle and controlled effects of inorganic nitrate may compensate for diminished endothelial function, and also has no reported tolerance. Therefore, with the increasing recognition of the limitations of organic nitrate supplementation, and continuing discovery of beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite, dietary inorganic forms may prove to be the optimum strategy for vascular health( Reference Omar, Artime and Webb 112 ).

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase Glu298Asp polymorphism and nitrate interactions

Variation in response to nitrates could be due to genetic polymorphisms. Healthy men retrospectively genotyped for the Glu298Asp polymorphism (7 GG and 7 T carriers), showed a differential postprandial BP response after consumption of beetroot-enriched bread compared with the control bread. A significantly lower diastolic BP in the T carriers was observed with a concomitant tendency for higher plasma NOx concentration. Despite the small study size these data suggests that carriers of the T allele, which limits endogenous NO production from endothelial eNOS( Reference Liu, Wang and Liu 113 ), were more responsive to dietary nitrate. Crosstalk between NOS-dependent pathway and the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway in control of vascular NO homeostasis could be a possible explanation for these observations( Reference Carlstrom, Liu and Yang 114 ), although future suitably powered studies are needed to confirm these findings. This nutrient–gene interaction is in contrast to that demonstrated for the same eNOS polymorphism and dietary flavonoids (described earlier), and confirms the differential proposed mechanisms by which flavonoids and nitrates impact on NO availability and vascular function.

Blood pressure

Dietary nitrate has been shown to reduced systolic BP and/or diastolic BP, and increase circulating nitrate/nitrite (see review( Reference Hobbs, George and Lovegrove 115 )). These findings are supported by more recent acute and chronic studies conducted in healthy younger populations (Table 1). A recent meta-analysis of four randomised clinical trials in older adults (55–76 years) revealed that consumption of beetroot juice did not have a significant effect on BP. However, consumption of beetroot juice containing 9·6 mm/d for 3 d( Reference Kelly, Fulford and Vanhatalo 116 ), or 4·8–6·4 mm nitrate/l for 3 weeks( Reference Jajja, Sutyarjoko and Lara 117 ) by older adults (60–70 years) significantly lowered resting systolic BP by 5 and 7·3 mmHg respectively, compared with the control. These inconsistent findings highlight the need for further studies to determine effects in older population groups.

Table 1. The acute and chronic effects of dietary or inorganic nitrate on blood pressure in healthy subjects since 2014

M, male; F, female; y, years; n/a, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

* Refers to differences from baseline.

It was concluded from data collated from eight studies conducted in patient groups that dietary nitrate may help to reduce BP in hypertensive subjects, but not in patients with type 2 diabetes, although only one study could be found in the latter population group( Reference Gee and Ahluwalia 118 ). Furthermore, minimal effects were reported in obese insulin resistant individuals( Reference Fuchs, Nyakayiru and Draijer 119 ), and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease despite relatively high doses of dietary nitrate (13·5 and 9·6 mm/d, respectively), although the intervention period was limited (2–3 d)( Reference Shepherd, Wilkerson and Dobson 120 , Reference Leong, Basham and Yong 121 ). In contrast consumption of beetroot juice (7·6 mm/d) by fifteen individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease significantly lowered diastolic BP by 8·2 mmHg (P = 0·019)( Reference Berry, Justus and Hauser 122 ). Additional studies are required to confirm these findings.

Platelet aggregation

Dietary and supplemental nitrate have been reported to significantly reduce platelet aggregation in healthy individuals( Reference Webb, Patel and Loukogeorgakis 88 , Reference Velmurugan, Gan and Rathod 110 , Reference Velmurugan, Kapil and Ghosh 123 ). However, a lack of effect was observed in women from one study. A proposed explanation for this sex difference was reduced soluble guanylyl cyclase activity( Reference Velmurugan, Kapil and Ghosh 123 ), a hypothesis supported by studies in mice( Reference Buys, Sips and Vermeersch 124 , Reference Chan, Bubb and Noyce 125 ), although further conformational studies are required.

Metabolic function

The consumption of sodium nitrate by eNOS deficient mice reversed features of the metabolic syndrome including improvements in BP, bodyweight, abdominal fat accumulation, circulating TAG levels and glucose homeostasis( Reference Carlstrom, Larsen and Nystrom 126 ). The improvements in glucose homeostasis by inorganic nitrate have been shown in a number of other mouse studies( Reference Nystrom, Ortsater and Huang 127 – Reference Khalifi, Rahimipour and Jeddi 130 ). For example, Khalifi et al.( Reference Khalifi, Rahimipour and Jeddi 130 ) examined the effects of dietary nitrate in glucose tolerance and lipid profile in type 2 diabetic rats, and found that supplementation of drinking-water with 100 mg/l sodium nitrate prevented an increase in systolic BP and serum glucose, improved glucose tolerance and restored dyslipidaemia in an animal model of hyperglycaemia. A possible mechanism for the beneficial effects of nitrate on glucose homeostasis may be the nitrite-mediated induction of GLUT4 translocation( Reference Jiang, Torregrossa and Potts 131 ), which enhances cellular uptake of glucose. More recent data have also shown that dietary nitrate may increase browning of white adipose tissue, which may have antiobesity and antidiabetic effects( Reference Roberts, Ashmore and Kotwica 132 ). However, there are few studies that have investigated the effects of dietary nitrate on glucose homeostasis in human subjects. Gilchrist et al.( Reference Gilchrist, Winyard and Aizawa 111 ) found that consumption of 250 ml beetroot juice (7·5 mm nitrate) for 2 weeks by individuals with type 2 diabetes increased plasma nitrate and nitrite concentrations, but did not improve insulin sensitivity measured by the hyperinsulinaemic isoglycaemic clamp. In support of this Cermak et al.( Reference Cermak, Hansen and Kouw 133 ) found that acute ingestion of sodium nitrate (0·15 mm nitrate/kg bodyweight) did not attenuate the postprandial rise in plasma glucose or insulin following an oral glucose tolerance test in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

In summary, organic nitrate is now considered to have important benefits on vascular health. While these benefits include the lowering of postprandial and longer-term BP in healthy groups, limited data in patient groups prevent the wider translation of these findings. Nitrate-rich foods have some reported benefits on measures of vascular function, with mechanistic links to increasing endothelial-independent NO availability through the reduction of nitrate to nitrite, and NO. The importance of the entero-salivary circulation and reduction of nitrate to nitrite by oral microbiota is essential for the functional effects of dietary nitrate. Evidence for the more controlled and sustained physiological effects of dietary nitrates on vascular health has prompted consideration of their potential advantage over the rapid effects of nitrate supplements. Further research is required to determine the lowest effective dose and specific mechanisms of action, particularly in patients with hypertension and cardiometabolic disease.

Interactions of nitrate–nitrite with flavonoids

Dietary flavonoids and nitrate affect vascular health by different mechanisms. Flavonoids are proposed to modulate endothelial-dependent NO release, and nitrates impact on NO production from nitrite intermediates and it is possible that their combined consumption may result in additive or synergistic vascular responses. Furthermore formation of NO and other reactive nitrogen species in the stomach is enhanced by increasing nitrite concentrations, lower stomach pH and the presence of vitamin C or polyphenols( Reference Carlsson, Wiklund and Engstrand 134 – Reference Peri, Pietraforte and Scorza 136 ). Bondonno et al.( Reference Bondonno, Yang and Croft 106 ) investigated the independent and additive effects of consumption of flavonoid-rich apples and nitrate-rich spinach. They found that the combination of nitrate and flavonoids did not result in additive effects on NO status, endothelial function or BP, although independent effects of flavonoid-rich apples and nitrate-rich spinach on these outcomes were reported. More recently, Rodriguez-Mateos et al.( Reference Rodriguez-Mateos, Hezel and Aydin 137 ) investigated interactions between cocoa flavanols and nitrate, and demonstrated additive effects on FMD response when cocoa flavanols and nitrate were consumed at low doses in combination. In addition, cocoa flavonoids enhanced nitrate-related gastric NO formation, supporting previous studies and suggests nutrient–nutrient interactions may modulate vascular function. Thus there is some evidence to suggest that nitrates and flavonoids, when consumed in combination, may exert additive effects on cardiovascular health, but due to the extremely limited data, confirmatory studies are required.

Conclusions

There is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that dietary flavonoids, particularly flavonols and anthocyanidins, improve vascular function and lower BP at doses achievable in diets that are high in foods such as fruit, vegetables, cocoa and teas. The potential mechanisms of actions are not fully understood, although increased NO availability via endothelial-dependent mechanisms have been proposed as a key modulator. Cell-signalling-mediated mechanisms are also important in both platelet and vascular function. Dietary inorganic nitrates are also dietary modulators of vascular health, primarily through the formation of NO via the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway. Promising effects of inorganic nitrate consumption on BP in healthy, hypertensive and other patient groups have been identified, although many of the current studies are limited in power and design, particularly those in specific patient groups. It is recognised that greater potential benefit may be gained from dietary nitrates compared with organic supplements, with the latter causing an immediate and severe reduction in BP and endothelial dysfunction. Research is required to determine whether dietary nitrates can be used in combination with hypotensive therapy, which may reduce or eliminate the requirement for medication and the associated side-effects. Consumption of diets rich in flavonoids and nitrates may be important in reducing CVD risk and promoting vascular benefit, although results have been inconsistent and more long-term studies are required to determine dose-dependent effects and the specific mechanisms of action.

Financial Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

J. A. L., A. S. and D. A. H. are joint authors of this manuscript.