- MDG

millennium development goals

The synergistic relationship between nutrition and the immune system has long been recognized(Reference Scrimshaw, Taylor and Gordon1, Reference Scrimshaw and SanGiovanni2). However, the advent of HIV/AIDS has brought the discussion of nutrition and immune function to prominence in recent times. In the past, the relationship between nutrition and infections has emphasized the vulnerabilities and risks of children, while with HIV/AIDS the discussion permeates all stages of life.

The interaction between nutrition and HIV/AIDS has biological and social consequences; impacts that affect the individual, household, community and nations. While research is still needed to better understand these processes, the evidence available suggests that nutrition, a key component of developmental processes, cannot be ignored in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

The present article provides a synopsis of the interaction between nutrition and HIV/AIDS and its implications for achieving the UN millennium development goals (MDG)(3).

The vicious cycle of HIV/AIDS and malnutrition

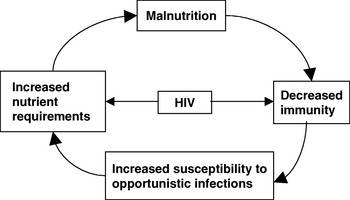

Malnutrition and HIV have similar deleterious effects on the immune system(Reference Jain and Chandra4–Reference Piwoz6). In both malnutrition and HIV there is reduced CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocyte numbers(Reference Chandra7, Reference Suttajit8), delayed cutaneous sensitivity, reduced bacteriocidal properties(Reference Beisel5) and impaired serological response after immunizations(Reference Faulk, Demaeyer and Davis9, Reference Kroon, van Dissel, de Jong and van Furth10). The synergistic effects of malnutrition and HIV on the immune system occur in a vicious cycle (Fig. 1) in which the decreased immunity associated with both conditions leads to increased susceptibility to infections (including HIV infection) that in turn lead to increased nutrient requirements, which if not adequately met lead to more malnutrition(Reference Piwoz and Preble11, Reference Semba and Tang12). Malnutrition, specifically wasting, is an important predictor of HIV progression to AIDS(Reference Malvy, Thiébaut, Marimoutou and Dabis13).

Fig. 1. Vicious cycle of HIV and malnutrition. (From Edwards(Reference Edwards23).)

HIV and malnutrition

The causes of malnutrition in HIV include: inadequate dietary intakes; nutrient loses; metabolic changes; increased requirements(Reference Macallan14, 15).

Inadequate dietary intake

HIV is associated with biological factors such as loss of appetite, gastrointestinal complications and oral and oesophageal sores that affect the individual's desire for food and ability to eat, leading to inadequate dietary intakes(Reference Suttajit8, Reference Piwoz and Preble11). In developing countries these biological effects are exacerbated by the social consequences of the disease, which typically culminate in food insecurity. Households affected by HIV/AIDS confront severe declines in the availability of food (both quantity and quality) because of a decrease or complete loss of the socio-economic contributions of sick household member(s) as well as their caregivers(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16). Lack of social support as a result of stigmatization and discrimination also contributes to reduced food availability and hence inadequate dietary intakes by those affected by HIV(Reference Drimie, Getahun and Frayne17).

Nutrient losses

Such losses are usually a result of malabsorption and/or diarrhoea(Reference Piwoz and Preble11). Malabsorption may be caused by changes in the intestinal lining resulting from the infection(Reference Hsu, Pencharz, Macallan and Tomkins18). It has been reported that poor absorption of carbohydrates and fats can occur at any stage of HIV infection in both adults and children, so that even asypmptomatic individuals can exhibit malabsorption(Reference Piwoz and Preble11), which leads to excess nutrient losses. Poor absorption of fat reduces absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamin A and E(Reference Semba and Tang12). Diarrhoea and vomiting can result from opportunistic infections and are also common side effects of HIV medications(Reference Chen, Misra and Garg19).

Metabolic changes

The immune system's response to HIV infection leads to metabolic changes that promote protein catabolism (associated with muscle wasting) and changes in fatty acid metabolism. During the acute-phase response pro-oxidant cytokines are produced, leading to increased utilization of antioxidant vitamins(Reference Friis20). Minerals such as Fe, Zn, Se and Cu are also sequestered for the production of antioxidant enzymes(Reference Enwonwu21, Reference Bogden and Oleske22). The immune response may also induce loss of appetite coupled with fever(Reference Bogden and Oleske22). The metabolic changes associated with HIV infection lead to increased energy and protein requirements together with inefficient utilization of nutrients(Reference Edwards23).

Increased requirements

The consequence of nutrient loses and changes in metabolism in HIV infection is increased requirements for both macro- and micronutrients. Energy requirements are elevated at different stages of the disease. Even during the asymptomatic phase there is a 10% increase in energy requirement above the level of intake recommended for a healthy individual of the same age, gender and physical activity level who is HIV negative; in the symptomatic phase the corresponding increase is 20–30%(15). Deficiencies in some micronutrients are common in individuals infected with HIV(Reference Friis20, Reference Fawzie24, Reference Piwoz and Bentley25). According to the WHO dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels may not be adequate to correct nutritional deficiencies in individuals infected with HIV(15); however, some micronutrient supplements have been shown to produce adverse outcomes in populations infected with HIV.

HIV-related wasting

The most common physical sign of nutrition inadequacy in HIV/AIDS is weight loss. The pattern of weight loss in individuals infected with HIV has been shown to be different from that of a healthy individual suffering from an acute illness(Reference Piwoz and Preble11). When an individual who is not infected with the HIV virus experiences an illness there is a protein-sparing effect in which fat stores are the first to be broken down to meet the elevated energy requirements associated with the illness. In HIV infection the opposite is true; body proteins are more likely to be the first to be broken down, to provide amino acids to fuel energy needs(Reference Hsu, Pencharz, Macallan and Tomkins18). Two patterns of weight loss have been observed in HIV: acute or rapid weight loss from secondary or opportunistic infections; chronic or slow weight loss from anorexia and gastrointestinal disease(Reference Macallan, Noble, Baldwin, Foskett, McManus and Griffin26).

Weight loss is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in populations living with HIV/AIDS. A 5% loss in weight is associated with risk for wasting, mortality and opportunistic infections(Reference Wheeler, Gilbert, Launer, Muurahainen, Elion, Abrams and Bartsch27). A weight loss of ≥10% is used to define wasting syndrome; a condition typically found in adult patients with AIDS in Africa(Reference Piwoz and Preble11, 28). Hospitalization usually occurs when there is a 20% loss in weight in the presence of opportunistic infections(Reference Edwards23).

HIV/AIDS, malnutrition and human development

The effects of malnutrition and HIV are synergistic and so they amplify their individual deleterious effects. Malnutrition exaggerates the effects of HIV on the individual by promoting fatigue and disease progression, resulting in increased morbidity and earlier death(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16). In the social context malnutrition aggravates the negative effects of HIV/AIDS on food and nutrition security(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16). Food security refers to physical and economic access to food in sufficient quality and quantity, while nutrition security is defined as secure access to food coupled with a sanitary environment, adequate health services and adequate care to ensure a healthy life for all household members(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16). The interaction between HIV/AIDS and food and nutrition security has been described as a vicious cycle in which food insecurity increases susceptibility to HIV exposure and infection and HIV/AIDS in turn increases vulnerability to food insecurity(Reference Gunter29). For many developing countries the effects of HIV/AIDS on food and nutrition security as well as other social effects of the disease impede progress to achieving the MDG(Reference Alban and Anderson30). How the interaction between HIV/AIDS and malnutrition encumbers each of the MDG will be briefly discussed.

Millennium development goal 1: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

HIV/AIDS-related morbidity and mortality coupled with malnutrition leads to a decline or loss in the productive capacity of individuals and households, resulting in a decline or complete loss of household income(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16, Reference Alban and Anderson30, Reference Gillespie, Haddad and Jackson31). Concurrently, families affected by HIV experience increased household expenses as a result of increased healthcare costs(Reference Alban and Anderson30, Reference O'Donnell32). Household assets are often sold to offset these effects(Reference Barnett and Rugalema33). The end result is more poverty and more food insecurity, and that moves households, communities and nations away from, rather than towards, achieving MDG1. Children whose parents die of AIDS have few or no assets, and therefore the effects of HIV/AIDS on poverty and hunger extend to future generations(Reference Bell, Devarajan, Gersbach and Haacker34).

Millennium development goal 2: achieve universal primary education

HIV/AIDS affects both the ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ side of education(Reference Alban and Anderson30). On the supply side, AIDS may cause absenteeism and mortality of teachers and other staff, thus lowering the availability and quality of learning opportunities for children(Reference Grassly, Kamal, Pegguri, Sikazwe, Malambo, Siamatowe and Bundy35). On the demand side, HIV/AIDS-associated poverty limits parents’ ability to pay school fees(Reference Alban and Anderson30). In addition, children may be required to drop out of school to contribute economically to their households or assist in providing care for sick household members. Children orphaned through HIV/AIDS who live with distant relatives or unrelated caregivers have lower school enrolment rates(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16). The capacity of children to learn may also be hindered because children from homes affected by HIV/AIDS may lack adequate nutrition for optimal cognitive development.

Millennium development goal 3: promote gender equality and empower women

The target associated with this goal is to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later than 2015(3). HIV/AIDS presents several challenges that can slow down progress in achieving this goal. In much of the developing world the prevalence of HIV is higher for women than for men, and women are more likely than men to be infected at younger ages(Reference Piwoz and Bentley25, 36). Thus, women are more vulnerable to the negative effects of HIV/AIDS on school enrolment, attendance and completion. HIV/AIDS therefore perpetuates gender inequality and women's powerlessness by limiting women's access to education(Reference Drimie, Getahun and Frayne17, 37).

Millennium development goal 4: reduce child mortality

HIV/AIDS contributes directly and indirectly to child mortality and thus is a major limitation to achieving this goal. Among the children 60% of those who contract HIV during the perinatal period die before the age of 5 years(Reference Alban and Anderson30). It is reported that the mean survival time for children who are HIV positive is 3 years(Reference Newell, Brahmbhatt and Ghys38). Indirectly, HIV contributes to child deaths through maternal HIV status(Reference Alban and Anderson30, Reference Newell, Brahmbhatt and Ghys38). Children born to mothers who are HIV positive are more likely to die than those born to mothers who are HIV negative(Reference Urassa, Boerma, Isingo, Ngalula, Ng'Weshemi, Mwaluko and Zaba39). The effects of HIV/AIDS on achieving MDG4 include issues related to: mother-to-child transmission and child survival(Reference Gillespie and Kadayila16); infant and young child feeding in the face of maternal HIV infection(Reference Piwoz and Bentley25); adult (especially mothers) HIV mortality and child well-being and survival(Reference Urassa, Boerma, Isingo, Ngalula, Ng'Weshemi, Mwaluko and Zaba39, Reference Deininger, Garcia and Subbarao40).

Millennium development goal 5: improve maternal health

An indicator for this goal is maternal mortality ratio. HIV/AIDS presents additional risks to mothers, thus hampering progress towards this goal. HIV infection is associated with higher risks of prenatal and child-birth complications, including miscarriage, anaemia and postpartum haemorrhage, which are important causes of maternal deaths(41). HIV also increases risk of infections such as malaria and pneumonia(Reference Alban and Anderson30).

Millennium development goal 6: combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

Progress in this goal is likely to have an important impact on all the other MDG. The relationship between nutrition and immunity suggests that nutrition interventions are key to making progress in this goal.

Millennium development goals 7 and 8: ensure environmental sustainability and develop global partnership for development

Although these issues are key issues, other pressing issues induced by HIV distract attention from these goals.

Conclusions

The effect of HIV/AIDS on human development is captured in the following quote from the 2005 WHO consultative meeting on Nutrition and HIV/AIDS held in Durban, South Africa: ‘HIV/AIDS is affecting more people in Eastern and Southern Africa than our fragile health systems can treat, demoralizing more children than our educational systems can inspire, creating more orphans that our communities can care for, wasting families, threatening food systems. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is increasingly driven by and contributes factors that also create malnutrition, in particular poverty’(42).

It is apparent that aggressive efforts to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS continue to be needed in much of the developing world, otherwise progress towards all the MDG will be frustrated. However, interventions to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS and to mitigate the social effects of the disease need to take into consideration the interaction between HIV/AIDS and nutrition. At the individual level nutrition therapy and related interventions contribute to the fight against HIV/AIDS by delaying the progression of HIV to AIDS, preventing mother-to-child transmission of the virus, preventing serious infections in individuals who are HIV positive and altering the severity and outcome of infections. Additionally, nutrition interventions can mitigate the social impacts of HIV/AIDS. Thus, the following quote by William Clay of FAO's Food and Nutrition Division may well be justified: ‘Food isn't a magic bullet. It won't stop people from dying of AIDS but it can help them live longer, more comfortable and productive lives’(43).