Introduction

Over the past few decades, health system transformations have led to the development of new models of health service delivery in many countries (Desmeules et al., Reference Desmeules, Roy, MacDermid, Champagne, Hinse and Woodhouse2012). Historically, health services in Ireland have evolved from a system which has been fragmented, overly hospital-centric, and focussed on delivering episodes of care, rather than an integrated and continuous model of care (Department of Health, 2016). Primary care predominantly entailed GP care, without the support of a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

In the last decade, there has been a significant shift in healthcare provision due to the launch of the Primary Care Strategy that aimed to transfer 90% of health services into the community, via primary care teams (PCTs) which include GPs, practice nurses, community nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, social workers, and home care services who provide a single point of contact into the Irish health system.

Musculoskeletal complaints are one of the most common reasons for seeking primary care and represent a significant economic and social burden to the healthcare system and the general public (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Kadam, Hayward, Porcheret, Young and Croft2010; Bornhoft et al., Reference Bornhoft, Larsson and Thorn2015). Between 20–26% of the general population seek healthcare for musculoskeletal complaints over the course of a year (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Kadam, Hayward, Porcheret, Young and Croft2010; MacKay et al., Reference MacKay, Canizares, Davis and Badley2010) and 14% of all primary care consultations are by patients with musculoskeletal problems (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Kadam, Hayward, Porcheret, Young and Croft2010). The change in mode of health service delivery in Ireland has resulted in the transfer of musculoskeletal physiotherapy services traditionally provided in acute hospital physiotherapy departments into primary care. Physiotherapists now play an active role in the assessment and management of musculoskeletal complaints in primary care (Desmeules et al., Reference Desmeules, Roy, MacDermid, Champagne, Hinse and Woodhouse2012), moving away from the role of the primary care physiotherapist previously in a domiciliary setting managing a varied caseload to being clinic-based managing a high proportion of musculoskeletal conditions. Evidence to date indicates that physiotherapy treatment of musculoskeletal conditions in primary care results in significant health benefits and cost savings (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Foster, Thomas, Peat, Phelan, Yates, Blenkinsopp and Sim2006; Nordeman et al., Reference Nordeman, Nilsson, Moller and Gunnarsson2006; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Whitehurst, Lewis, Bryan, Dunn, Foster, Konstantinou, Main, Mason, Somerville, Sowden, Vohora and Hay2011).

Delivering measurable and sustainable health service delivery improvements is a key metric for healthcare policy makers and clinicians (Roberts, Reference Roberts2013). Evaluation of these care models to date has broadly focussed on quantitative metrics of the process and outcomes of care including waiting times, recovery times and economic evaluations of the service (Desmeules et al., Reference Desmeules, Roy, MacDermid, Champagne, Hinse and Woodhouse2012) but qualitative analysis can provide a deeper understanding from the perspective of key stakeholders. We recently explored physiotherapists’ experiences of providing musculoskeletal physiotherapy in an Irish primary care setting using a qualitative methodology, to gain an insight into the current facilitators and barriers in service delivery and on-going professional development needs (French and Galvin, Reference French and Galvin2017). Four major themes emerged from these focus groups including the value of team working, the evolving role of the physiotherapist in primary care, environmental contexts (including physical infrastructure and interaction with acute sites) and factors associated with engagement in continuous professional development (CPD). Following on from an exploration of clinicians’ perspectives, we aimed to obtain the perspective of physiotherapy managers on the provision of musculoskeletal physiotherapy services in primary care in Ireland. We also aimed to uncover the barriers and facilitators to musculoskeletal service delivery and to gain an insight into professional development needs among physiotherapy staff.

Methods

Study design and participants

We used a phenomenological approach to explore physiotherapy managers’ views of the delivery of musculoskeletal physiotherapy services in an Irish primary care setting. The aim of a phenomenological theoretical approach is to set aside current knowledge and review concepts through the eyes of the individual experiencing them (Husserl, Reference Husserl1970; Lowes and Prowse, Reference Ladyshewsky2001). Using this approach, researchers take the view that there is no correct answer, but that each individual has a range of subjective experiences. The aim is to identify, understand, describe and maintain the subjective experiences of research participants and by doing so to develop new understanding (Husserl, Reference Husserl1970; Lowes and Prowse, Reference Ladyshewsky2001). In this study, the purpose of the interview was to enhance the researchers’ understanding of the lived-in experience of managing musculoskeletal physiotherapy services from the perspective of these stakeholders. We considered each participant as an individual who interpreted the question in their own unique way (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2017). Semi-structured individual interviews allowed exploration of the research themes to unearth new information that was not anticipated prior to the interviews.

A list of managers (n=36) was obtained from the Health Service Executive (HSE). Purposive sampling was used to ensure a geographical spread of primary care physiotherapy managers in both rural and urban settings. Potential participants were sent a participant information leaflet and asked to contact the researchers if they were interested in taking part. Written informed consent was obtained prior to conducting the interviews. The interview questions (Online Supplemental Material) were based on previous relevant literature (Minns and Bithell, Reference Minns and Bithell1998; Minns Lowe and Bithell, Reference Minns Lowe and Bithell2000), together with elements that the researchers considered pertinent. One researcher (H.F.) conducted the interviews at a location and time convenient to study participants. The researcher, an academic physiotherapist with a musculoskeletal clinical background, received qualitative research training and has previous qualitative research experience (French and Galvin, Reference French and Galvin2017). Each interview was audio recorded for later transcription. While several methods of determining data saturation are proposed (Fusch and Ness, Reference Fusch and Ness2015), we considered data saturation as achieved when the ability to obtain additional new information was attained (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2005). The Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) standardised reporting guidelines (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007) were adhered to in the conduct and reporting of the study.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed by a professional transcriber. To ensure trustworthiness of the data, member checking was done with participants. Transcripts were examined using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), where transcripts were initially read in their entirety to get a sense of the whole conversation and, using line by line analysis, patterns and themes were identified and documented. Two researchers (R.G. and H.F.) independently coded and analysed the transcripts to identify major and minor themes using an iterative process. The suitability of the coding system was examined during this process and patterns both consistent and inconsistent with the codes were explored. The codes were designed to be understandable definitions, which could be easily interpreted and used by other independent coders. Codes were grouped into minor themes and subsequent major themes following a number of consensus meetings.

Findings

Five one-to-one interviews were held across the Republic of Ireland in two urban and three rural areas. Interviews lasted between 37 and 126 min (mean=74 min, SD=33 min). Data saturation was deemed to have occurred after the fifth interview.

Overview of musculoskeletal service provision in primary care

The participating managers were responsible for between nine and 26 PCTs. A mix of self-referral based on clinical need and referral by medical card entitlement existed. All managers reported that most referrals to physiotherapy were musculoskeletal, with the GP being the primary referral source. Musculoskeletal services were based in various locations, from single rooms in small health centres to purpose-built centres with a combination of cubicles and open gym space. Two managers reported future planned physical infrastructural development. Physiotherapy appointment times varied between 30 and 45 min depending on whether a first assessment or return visit was required. Attempts to reduce treatment times to improve service efficiencies proved challenging due to the chronic and complex physical and mental health needs of many patients. Non-attendance of patients resulted in the development of strict non-attendance policies and opt-in services to optimise service efficiency across the sites. Administrative support was generally ad hoc, limited and unreliable, with physiotherapists commonly absorbing administrative duties. All managers reported that staffing levels had reduced over recent years due to economic restrictions within the HSE, predominantly due to posts being vacated when staff went on maternity leave or resigned from their posts.

Qualitative themes

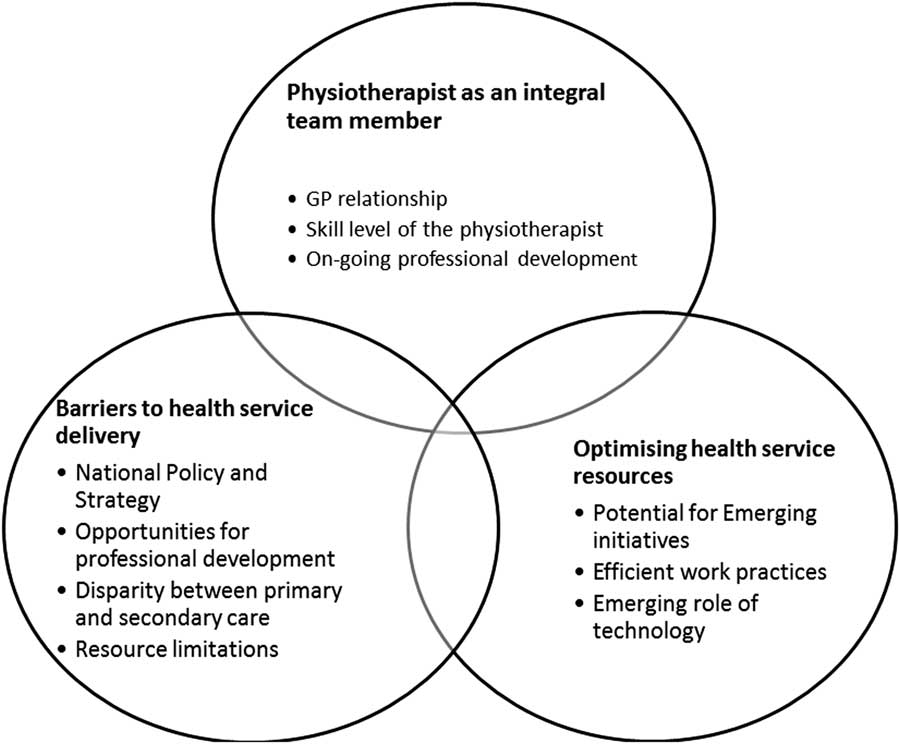

Three major inter-related themes emerged from the interviews: the physiotherapist as an integral team member, optimising health service resources and barriers to health service delivery. Figure 1 displays these themes and associated subthemes.

Figure 1 Overview of major and minor themes

The physiotherapist an integral team member

Within this theme, both positive and negative aspects of working in the MDT in primary care were identified. The managers perceived the physiotherapist as a central member of the PCT, with a very positive relationship with the GP:

‘over about the last three to four years referrals have doubled overall, GP referrals have tripled and I’d say the bulk of that is because they’re aware of primary care teams and because they’ve engaged somewhat with the primary care process and are aware that “oh, there’s a physio for this primary care team, we’ll refer there”’. (M1)

although a full understanding of the role of physiotherapy within the PCT appeared to be a barrier:

‘….the physiotherapist on the primary care team is the gateway to a range of physiotherapy services. Because GPs mightn’t, they didn’t know, they really had no understanding of the range of services that are being provided by acute setting and community’.(M2)

Physical location of the MDT in the same building, accommodation sharing with other MDT members and attendance at team meetings were also considered to enhance MDT working. However, while physiotherapists engaged well within the PCT, there was potential risk of isolation from their professional group.

The experience level of junior grade physiotherapists was also a subtheme. Many had completed musculoskeletal Masters degrees and were longer than three years qualified, which is the lower cut-off for promotion to senior grade in the Irish public sector system. Although this was a positive attribute for service delivery, it was a negative factor for the therapists themselves due to limited career progression:

‘They’re qualified maybe six years, but I suppose that’s a negative as well in that there is no prospect of a senior post coming up and they do say it to me “oh, I’m going to be a staff grade forever”’. (M4)

The challenge of being a generalist physiotherapist in primary care, treating patients across a spectrum of conditions and ages, was acknowledged as conflicting with developments towards professional body specialisation:

‘The employer is looking for generalists and within the profession we’ve been working towards specialism. And in some ways the employer is not interested in any job description that has specialist in it’. (M2)

Engaging in CPD was an important role of the primary care physiotherapist, with many managers identifying work-based CPD activities such as in-service training, journal clubs and practical skills training were important to maintain musculoskeletal competency. Regular professional development planning was used to identify skills gaps and training needs. Releasing staff to attend external CPD events was identified as a challenge for all managers. All reported there was no formal HSE policy on study leave for CPD, unless undertaking Masters level education, which frequently resulted in personal financial investment by the therapists. CPD opportunities funded by the HSE were welcomed but lack of standardised policies from the HSE was frustrating for all.

‘What I find with, with my staff is, that, you know, they, they spend a fortune on going to CPD. They really are, really great’. (M4)

Optimising health service resources

This theme focussed on recent initiatives to improve efficiencies in health service delivery as well as emerging opportunities for service development. Managers highlighted a number of positive elements to the evolving nature of health service delivery. These included an increase in the range of services offered to patients including gym-based exercise programmes, orthotics clinics and self-management programmes.

‘for the general exercise class, we would have all age groups. And we have circuit based interval training and we find that the best way of managing very mixed case loads …. So the aim with these network services and we, is to reduce number of treatments and you know, promote self-management’. (M5)

The increased number of primary care sites was also noted as a positive development which helped to stabilise patient demand. Areas for related service development where current gaps were identified included mental health services, health promotion and women’s health.

‘I’m very sorry that we didn’t have an option on the mental health because actually to me that’s the big miss’. (M2)

Community partnerships and community engagement were highlighted as important elements of service delivery and health promotion in primary care.

‘We do the move for health initiative every year and we try, you know either go out to schools or something like that. We’ve done large pieces around the chronic disease of trying to kind of roll it out. We’ve done work with the sports partnership in terms of the link between obesity and chronic disease’. (M2)

Self-referral was also perceived as a positive initiative in one centre as it served to optimise attendance and actively involve patients in self-management of chronic conditions.

Staff availability, engagement and collaboration were described as key factors in optimising service delivery. The role of administrative staff was particularly valued in optimising service efficiency and effectiveness. Due to financial constraints, more efficient work practices were vital to maintain optimal patient care

‘We have adapted over the last three to four years and, as I say, with twice as many referrals and virtually the same number of staff, is the equivalent of our staff being halved’. (M4)

Provision of pre-qualification student physiotherapist practice education placements served to enhance students’ exposure to a continually evolving model of care as well as actively managing waiting lists:

‘The third year students were assisting in group work last year, in this area and it was really positive. So as well as a learning experience, they’re a tremendous resource to us. And in our health stats it showed’. (M5)

Staff rotations between acute and primary care settings served to optimise clinical exposure to different client groups. Junior physiotherapists were also provided with informal mentors at some sites. Invitation of guest speakers to deliver in-services and evening lectures encouraged interprofessional CPD. Joint academic and clinical partnerships served to build research links across the academic and clinical settings.

The emerging role of technology to enhance service delivery was also noted across sites, both for clinical care and as an adjunct to administrative support such as managing appointments and teleconferencing:

‘One of the requests we had at the start of primary care, was to have a shared file for the MDT and it hasn’t happened. And it’s, it really is a very simple, I mean, the nurses now have iPhones for the infant checks on home. So I think it’s starting and I do feel the technology could really assist us’. (M2)

Central appointments services were proposed to streamline services and standardise practices, but currently not in situ. Additionally, standardisation of policies around budgets and equipment procurement and allocation was noted as an area for improvement.

Barriers to health service delivery

A number of factors that impacted on service delivery and development were highlighted. Lack of national strategy around primary care service provision was perceived to result in poor standardisation of services across primary care sites:

‘Well, the barriers are that the primary care teams aren’t being properly managed. And the whole issue between line management, of different disciplines. And setting, you know, a lot of the initiatives in primary care team are individual led, rather than strategy led’. (M5)

Managers also highlighted the need for a national strategy around managing certain health conditions in primary care such as mental health and chronic disease. All noted limited opportunities for CPD planning and promotion within the profession. Issues with staff retention both within physiotherapy and across the MDT were also raised:

‘But I just think it’s atrocious because I have to ask permission from the general manager to approve unpaid leave. So that this individual physiotherapist could spend €12000 or 16000 on the Masters and you know lose a month on unpaid leave’. (M2)

The nature and source of referrals also varied across primary care sites and inappropriate referrals were considered as a barrier to service delivery. Limited resources, including personnel, infrastructure and equipment also impacted negatively on service delivery. Reduced staffing, restricted funding and lack of auxiliary services including administrative and IT support were cited as significant barriers to optimal service delivery:

‘Some primary care teams would have clerical support. I kind of, again it’s at different levels, some there’s kind of gold standard where clerical support acts as a receptionist physically in the building. They make appointments, take cancellations, rearrange appointments, manage the physios’ diary, usually that’s electronically, and maintain a database of referrals and just kind of general sort of clerical support. So that’s the gold standard, that’s not everywhere’. (M4)

‘In the sites, we have proven that we could increase productivity by 20%, if we had dedicated admin’. (M5)

Lack of cohesion both within primary care and across primary and secondary care services also impacted on service provision. Health and safety issues were highlighted as a concern, with a perceived increase in the incidence of aggression towards staff.

‘Violence and aggression is a looming and large problem, employee health and safety has been largely hospital based, it’s now in the last 6 or 8 months just gone out and started to take on seriously the issues in community care’. (M2)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore physiotherapy managers’ views of the delivery of musculoskeletal physiotherapy services in an Irish primary care setting. Three major themes emerged from the interviews including the physiotherapist as an integral team member, optimising health service resources and barriers to health service delivery.

The managers reported that physiotherapists were considered integral team members based on anecdotal feedback. Physiotherapists have been previously identified as playing a pivotal role in PCTs by other team members, particularly in musculoskeletal health and chronic disease management, due to expertise in physical activity counselling and exercise prescription (Dufour et al., Reference Dufour, Lucy and Brown2014). The 2017 HSE National Service Plan has identified the development of integrated care programmes for chronic disease prevention and management as a priority area in primary care (HSE, 2017). However, managers perceived there was a lack of knowledge of what the physiotherapist does which has previously been identified amongst GPs, in part due to the traditional biomedical model of patient care (Paz-Lourido and Kuisma, Reference Paz-Lourido and Kuisma2013). To this end, there is a shift internationally to increase opportunities for interprofessional education (IPE) at undergraduate level which should continue in the workplace setting (Paz-Lourido and Kuisma, Reference Paz-Lourido and Kuisma2013). While uniprofessional education remains the dominant model for delivering education for health and social care professionals, IPE is recognised as important to improve global health service delivery (World Health Organisation, 2010).

Interprofessional team working in the primary care setting is key to understanding each other’s role and this can be achieved through ‘top down’ methods such as organisational issues related to policy, structure, space and time which can foster the ‘bottom up’ strategies such as the informal communication that should not be underestimated as an important method to enhance shared clinical decision making (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Pullon and McKinlay2015).

Lack of clear HSE policy was problematic in trying to balance staff’s training needs, service development requirements and service delivery. High skill levels provide the opportunity for physiotherapists to be gatekeepers in the management of musculoskeletal services in primary care (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Foster and Croft2013). Physiotherapists are specifically trained to manage symptoms and improve function and physical activity which is a key objective in the management of musculoskeletal disorders (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Foster and Croft2013). Previous research has identified that GPs lack confidence in managing such conditions (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Austin, Campion-Smith, Carr and Mann2007) and direct access to physiotherapy can reduce waiting times, GP workload, improve clinical outcomes and increase patient satisfaction (Holdsworth and Webster, Reference Holdsworth and Webster2004; Ludvigsson and Enthoven, Reference Ludvigsson and Enthoven2012; Mallett et al., Reference Mallett, Bakker and Burton2014; Goodwin and Hendrick, Reference Goodwin and Hendrick2016).

Whilst the need for specialisation with physiotherapy is considered an important focus within the profession worldwide, the need for generalist physiotherapists, akin to the GP in medicine is also recognised (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Oldmeadow, Cromie and Grant2003; Bennett and Grant, Reference Bennett and Grant2004). There is a move towards specialisation within primary care with the development of GPs with special interests (GPwSIs) and nurse practitioner roles in primary care. In the United Kingdom, multidisciplinary musculoskeletal clinics at the primary–secondary care interface provide a ‘one-stop shop’ where physiotherapists and GPwSIs triage patients into appropriate management pathways (Sephton et al., Reference Sephton, Hough, Roberts and Oldham2010; Roddy et al., Reference Roddy, Zwierska, Jordan, Dawes, Hider, Packham, Stevenson and Hay2013). Such a model has the potential to improve health service delivery in Ireland with appropriate infrastructure, thereby addressing the second theme of optimising service resources. Initiatives were used to improve service efficiency, such as providing student placements. Previous research has shown that productivity does increase by taking students (Ladyshewsky, Reference Lowes and Prowse1995; Holland, Reference Holland1997). Traditionally, student physiotherapy placements were provided in secondary care in Ireland, supported by dedicated practice tutors. A recent survey has identified support for provision of placements in primary care, although clear planning and collaboration with all relevant stakeholders would be required (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Perrier, Goldman, Freeth and Zwarenstein2013; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Cusack and O’Donoghue2014). Use of information and communication technology may have the potential to increase productivity through the use of mobile phone messaging systems to increase adherence (Car et al., Reference Car, Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek and Atun2012). Technology potentially can allow patients to self-manage their own health and wellness at home (Montague, Reference Montague2014). For example, smartphone apps have been effectively shown to implement behaviour change around physical activity (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, Hayes, Casey, Glynn, Alvarez-Iglesias, Newell, O. Laighin, Heaney, O’Donnell and Murphy2014). Self-referral may provide a feasible, cost-effective pathway comparable with GP referral (Mallett et al., Reference Mallett, Bakker and Burton2014).

Barriers to service delivery included limited opportunities for capacity building and promotion both within the profession and across the MDT. While local initiatives were employed to support CPD, the broader requirement for the development of a research culture in primary healthcare has been highlighted in several policy initiatives nationally and internationally (Farmer and Weston, Reference Farmer and Weston2002; Department of Health and Children, 2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Miyazaki, Borkowski, McKinstry, Cotchet and Haines2015), and evidence suggests a lack of success or skill among primary care health professionals in more advanced research activities including study design, data analysis, writing for publication and mentorship of junior colleagues/clinicians in research (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Miyazaki, Borkowski, McKinstry, Cotchet and Haines2015). Reduced staffing, limited funding and lack of auxiliary services were cited as significant barriers to service delivery in the current study, but these also serve as barriers to research capacity building in primary care. In an Irish context, although primary care practitioners appear to recognise the importance of research in primary care, engagement with research is poor across different professional groups. Multiple factors have been identified to explain this including a lack of research culture, absence of a supportive infrastructure including protected time, funding, research skills and supervisory support (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, O’Riordan, MacFarlane, Newell, Iglesias, Whitford, Cantillon and Murphy2009).

At the time of interviewing, lack of national strategy around primary care service provision was perceived to result in a lack of standardisation of services delivery across primary care sites. Recent HSE service plans identify development of integrated clinical care pathways across acute, primary care, community and residential care settings as high priority by working with medical, nursing and therapy leads to develop and improve processes (HSE, 2017). A recent systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of integrated models of healthcare delivered at the primary–secondary interface demonstrated improvements in the management of conditions and service delivery at a modestly increased cost (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Burridge, Zhang, Donald, Scott, Dart and Jackson2015) but research in an Irish context would be required.

In summary, whilst three overarching themes were identified, there is much overlap across the subthemes. Skilled physiotherapists who can potentially improve efficiencies within the primary care system by absorbing musculoskeletal caseloads traditionally taken by GPs require on-going training and professional development, including research training. Development of more streamlined processes and use of technology can also improve work efficiency and effectiveness. Many of these changes need to be developed at national level based on national strategy with appropriate resource allocation.

Implications of this research

Some implications for both practice and research arise from this research. A greater understanding of the role of the physiotherapist within the PCT is required, both from healthcare users and other MDT members. Whilst the role of the physiotherapist as a gatekeeper for musculoskeletal conditions in secondary care is well established, the potential for such a role within primary care warrants further exploration. This could be a potentially cost-effective way of managing waiting lists and freeing up the GP’s time to see patients with more complex medical needs (Ludvigsson and Enthoven, Reference Ludvigsson and Enthoven2012; Goodwin and Hendrick, Reference Goodwin and Hendrick2016). IPE should be an integral part of the healthcare undergraduate programmes and should continue through the healthcare professional’s career to facilitate the development of a ‘collaborative practice-ready’ healthcare system (World Health Organisation, 2010). Greater involvement of physiotherapists in health policy and decision making is critical and representation of physiotherapy within the Department of Health in Ireland is crucial to facilitate strategic planning of services.

Study strengths and limitations

This is the first known study to explore the perspectives of physiotherapy managers regarding musculoskeletal physiotherapy services in primary care in Ireland and complements previous research which explored the views of senior and junior grade therapists (French and Galvin, Reference French and Galvin2017). Methodological rigour was ensured using strategies such as verification of data, participant checking, independent thematic analysis, sampling sufficiency and independent data analysis. However, we acknowledge that additional methods to ensure rigour have also been proposed including the establishment of intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of the codes identified (Miles and Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). The themes were developed only from physiotherapy managers’ opinions. The views of other stakeholders such as GPs, other MDT members, HSE managers and patients should be explored to provide a more thorough understanding of the relevant issues in musculoskeletal physiotherapy in primary care.

In addition, study findings may have been influenced by the authors’ research and clinical experience and should be interpreted within this context. Although a geographical representation was obtained with saturation of data, our sample of five managers could be considered small.

Conclusion

This study identified various complex inter-related factors that impact on musculoskeletal service delivery in primary care from the perspective of physiotherapy managers. These include the physiotherapist as part of the MDT, initiatives to optimise resources and barriers which impede effective service delivery. Future research should explore the views of other stakeholders to provide a more thorough understanding of the relevant issues affecting musculoskeletal service provision. Such findings can be used to inform service delivery and enhance patient care in this setting.

Acknowledgements

Emma Benton, HSE Therapy Professions Advisor who provided information regarding the structure of therapy services in primary care and the Physiotherapy managers who gave their valuable time to take part in this study.

Ethical Standards

The project received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (REC-00751).

Financial Support

This work was supported by an unrestricted bursary awarded from the Irish Society of Chartered Physiotherapists on behalf of O’Driscoll O’Neil insurance.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423617000469