Background

It is estimated that up to 84% of the general population will experience an episode of low back pain (LBP) during their lifetime and recurrence rates are high (Airaksinen et al., Reference Airaksinen, Brox, Cedraschi, Hildebrandt, Klaber-Moffett, Kovacs, Mannion, Reis, Staal, Ursin and Zanoli2006). The prevalence and incidence of LBP increases with age, and adults of working age are the most vulnerable group (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Karppinen and Samartzis2017). Prevalence is higher in high-income countries than in middle- or low-income countries (Hoy et al., Reference Hoy, Bain, Williams, March, Brooks, Blyth, Woolf, Vos and Buchbinder2012) and non-specific LBP is one of the most common reasons for consulting a primary care physician. It is becoming a major global health concern and is responsible for rising costs (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Abajobir, Abate, Abbafati, Abbas, Abd-Allah, Abdulkader, Abdulle, Abebo, Abera and Aboyans2017; Dorner, Reference Dorner2018). Non-specific LBP is defined as axial/non-radiating pain occurring primarily in the back with no signs of a serious underlying condition (such as cancer, infection or cauda equine syndrome), spinal stenosis or radiculopathy or another specific spinal cause (such as vertebral compression fracture or ankylosing spondylitis) (Va/DoD, 2017).

Primary health care professionals are involved in most of the care of patients with non-specific LBP (Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Hayden and Magee2017), but are confronted with organizational, temporal and/or personnel constraints due, for example, to an oversupply of treatment options, time pressure and/or lack of confidence in new approaches to care (Traeger et al., Reference Traeger, Buchbinder, Elshaug, Croft and Maher2019).

In recent years, comprehensive research has sought to evaluate the management of LBP, but recommendations are not often based on high-quality and patient-oriented evidence (Ebell et al., Reference Ebell, Sokol, Lee, Simons and Early2017). The aim of evidence-based clinical pathways is to collect recommendations from international guidelines and to develop a structured plan of care with which to enhance quality and optimize the use of resources (Toy et al., Reference Toy, Drechsler and Waters2018).

The aim of this study was to systematically identify, characterize and analyze recommendations concerning the primary care of people with non-specific LBP from evidence-based international guidelines published in high-income WHO ‘Stratum A’ countries.

Methods

Literature search

To identify current guidelines on non-specific LBP, we initially searched PubMed and the guideline databases of the Guideline International Network (G-I-N), the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, 2017), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), from 2013 to May 2018. In addition, we hand searched the reference lists of included publications and the websites of medical associations that deal with the topic, and contacted experts in the field. In September 2020, an update search was performed in PubMed and the guideline databases, with the exception of NGC, which was closed in July 2018. We used a combination of Medical subject headings (MeSH) and key words associated with back pain as search terms. The search strategies are described in the appendix (electronic supplementary materials).

Selection process

Guidelines had to fulfill all of the following criteria to be included in our systematic overview:

-

A target population of people, any age and sex, with non-specific LBP (LBP not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology (eg, infection, tumor, osteoporosis, fracture, metabolic disease, inflammatory arthritis)

-

The inclusion of recommendations on diagnosis and/or therapy for non-specific LBP

-

Published in an industrial nation, as defined by the WHO Health report 2003 (Stratum A) (WHO, 2003)

-

The guideline development process had to include a systematic search for evidence and information on Level of Evidence (LoE) and/or Grade of Recommendation (GoR)

-

Published in English or German

-

Published in 2013 or later and still valid (documentation of expiry date). The cut off date of 2013 was chosen because there is an international consensus that guidelines should be updated at least every five years. Guidelines published before 2013 were classified as non-valid.

Two reviewers (C.Z., K.J. and T.S.) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all identified publications for eligibility. The full texts of potentially eligible publications were examined by two reviewers (C.Z., K.J. and T.S.) independently. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, or with the help of a third reviewer. We excluded publications with identical citations as duplicates. Different publications on the same guideline from different literature sources were all included and cited, and the most recent recommendations extracted.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of all included guidelines was assessed using the validated guideline appraisal tool of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Collaboration (AGREE II) (AGREE Next Steps Consortium, 2017; Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Kho, Browman, Burgers, Cluzeau, Feder, Fervers, Graham, Grimshaw, Hanna, Littlejohns, Makarski and Zitzelsberger2010). It consists of 23 items grouped into six domains, and an overall guideline quality score. Each item, as well as overall guideline quality, is rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 point (strong disagreement/poor quality) to 7 points (strong agreement/high quality). For each domain, we calculated the scaled domain score by summing up the scores assigned to the respective items by the individual reviewers, and the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for the domain (Hoffmann-Esser et al., Reference Hoffmann-Esser, Siering, Neugebauer, Lampert and Eikermann2018). To distinguish between high- and low-quality guidelines, we rated the guidelines. Overall assessment scores ≥ 6 points were indicating high, scores between 4 points and 5.9 points moderate and scores <4 points low quality. Two reviewers with experience in guideline quality assessment (T.S. and C.K.) appraised each guideline independently. We resolved any disagreements by consensus or by consultation with a third review author (KH, KJ).

Data extraction

Data extraction for each study was performed by two independent reviewers (C.K. and C.Z.), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We used a predesigned data collection form to extract data on title, main topic of the guideline, publishing organization, country of origin, year of publication and the number of included recommendations.

All recommendations concerning individual patient management in primary care were extracted, along with their respective GoRs and/or LoEs. We excluded general recommendations directed at the health care system as a whole, such as public health strategies. Since the guidelines used differing approaches to grade the strength of their recommendations, we developed a standardized grade of recommendation system for this overview (GoR ‘A’ for strong, GoR ‘B’ for moderate, GoR ‘C’ for weak, GoR ‘D’ for very weak recommendations and ‘EC’ for expert consensus).

To provide a systematic overview of the international guidelines, we grouped all included recommendations by topic, and compared them to each other.

Findings

Findings of the literature search

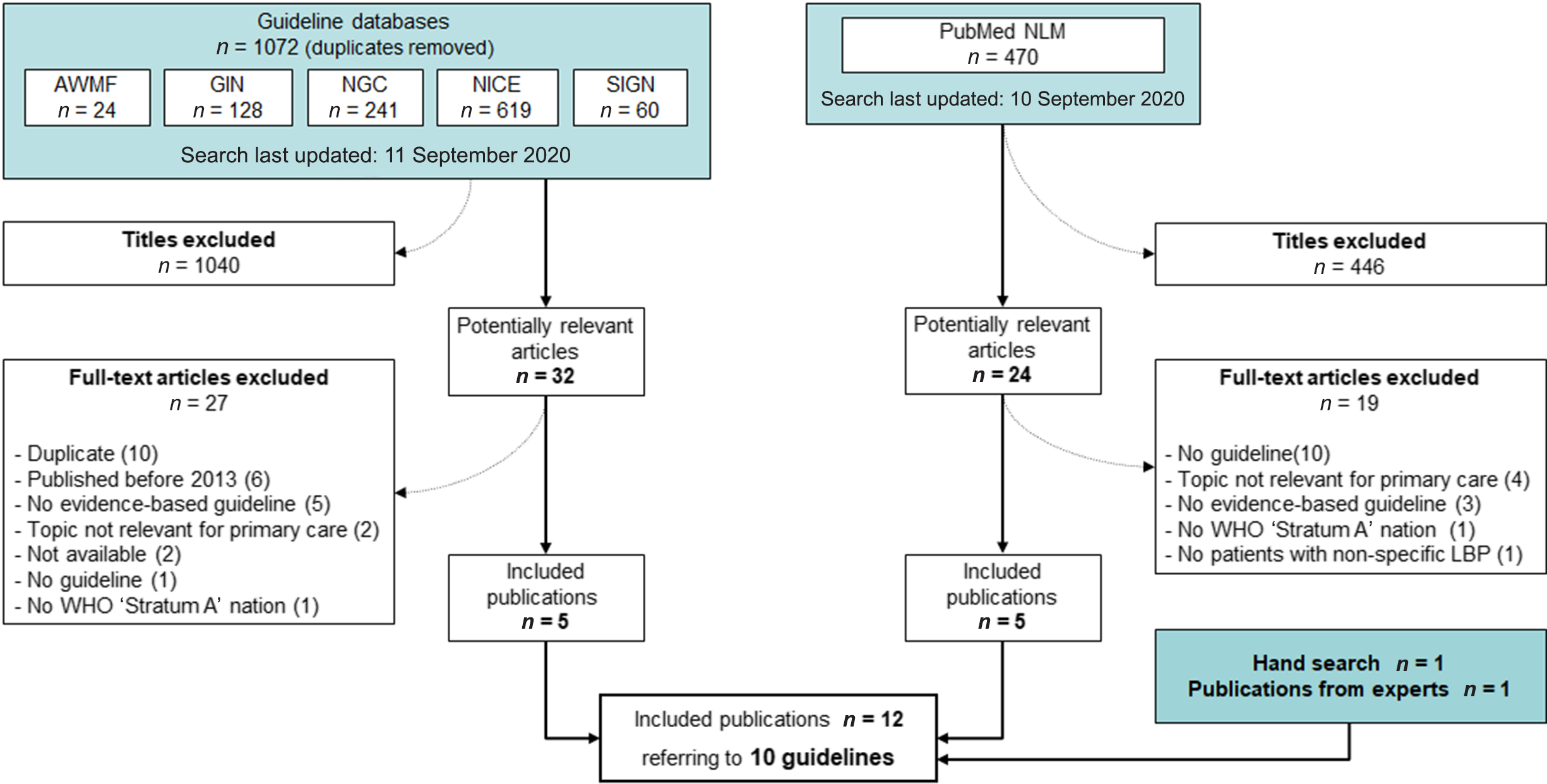

Our search in guideline databases and in PubMed yielded 1542 results (date of last search: 11 September 2020). We excluded 1486 publications by consensus on the basis of their titles and abstracts, leaving 56 publications for further examination. After examining the full text of the selected publications, we included 10 as relevant for our overview. The additional hand search and contacting experts in the field resulted in two further relevant publications. Thus, 12 publications on 10 guidelines (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017; Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Malik, Carville and Ward2017; KCE, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; Wenger and Cifu, Reference Wenger and Cifu2017; BMASK, 2018; CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020) were included in the overview. Details on the literature search and selection process can be found in Figure 1. Details of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are reported in the appendix (electronic supplementary materials).

Figure 1. Flow chart of guideline selection process.

Guideline characteristics

Nine guidelines addressed the overall management (diagnosis and/or treatment) of people with LBP (NICE, 2016; ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017; KCE, 2017; NVL, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020). The remaining guideline dealt with the specific aspect of spinal manipulative therapy (CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018). Five guidelines were issued by professional associations from the US (ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017; VA/DoD, 2017; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020). One guideline each was published in the UK (NICE, 2016), Canada (CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018), Germany (NVL, 2017), Belgium (KCE, 2017) and Austria (BMASK, 2018). Guidelines’ publication dates ranged from 2016 (NICE, 2016) to 2020 (NASS, 2020). For details on the characteristics of the included guidelines, see Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included guidelines

ACOEM = American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; ACP = American College of Physicians; BMASK = Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz; CCGI = Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative; DoD = Department of Defense; ICSI = Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; KCE = Belgian Health Care Knowledge Center; LBP = Low Back Pain; NASS = North American Spine Society; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NVL = Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie; VA = Veterans Affairs.

The number of recommendations extracted from each guideline ranged from 178 from the ACOEM guideline (ACOEM, 2019) to 3 recommendations from the ACP, which gave only very general recommendations (ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017).

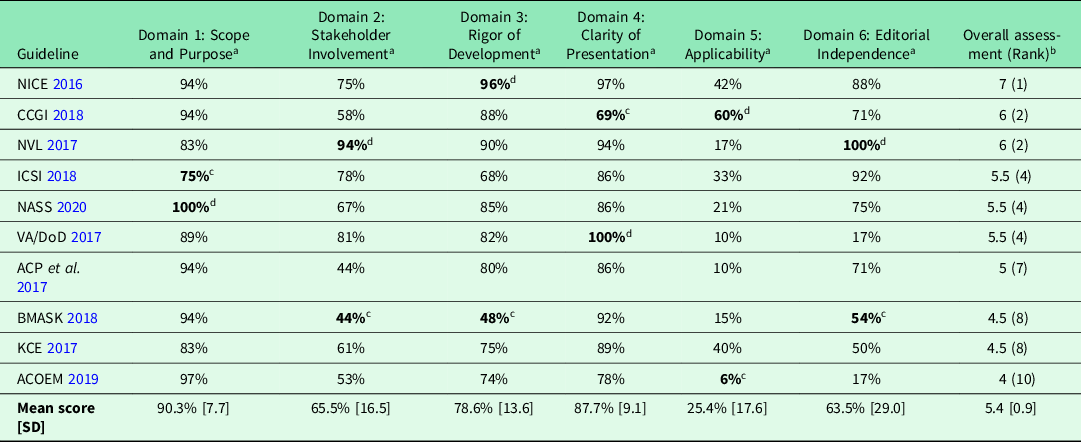

Quality of included guidelines

The mean overall AGREE II score was 5.4 (SD 0.9) out of a maximum of 7 points. Three guidelines were judged to be of high quality (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018) and seven of moderate quality (ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017; ICSI, 2017; KCE, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020). We judged no guideline to be of low quality. The guideline with the highest score was the NICE-guideline ‘LBP and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management’ (NICE, 2016). The guideline rated lowest was ‘Low back disorders’ developed by ACOEM (ACOEM, 2019). An examination of the individual AGREE II domains showed that most of the guidelines achieved high scores in ‘Scope and Purpose’, in which guideline objectives are analyzed, and disease and target populations described, and in ‘Clarity of Presentation’, which evaluates the clarity of recommendations and ease of their identification. The AGREE II domain with the lowest scores in most of the guidelines was ‘Applicability’, which analyzes the description of potential facilitators and barriers to the use of the guideline, potential resource implications and monitoring criteria. Table 2 shows all AGREE II domain scores and the overall quality scores for each guideline.

Table 2. Methodological quality of the included guidelines (AGREE II scores)

a Scaled domain scores: percentage of maximum possible score.

b Overall assessment: 1 point = lowest possible quality, 7 = highest possible quality.

c Lowest score.

d Highest score.

ACOEM = American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; ACP = American College of Physicians; BMASK = Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz; CCGI = Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative; DoD = Department of Defense; ICSI = Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; KCE = Belgian Health Care Knowledge Center; NASS = North American Spine Society; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NVL = Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Overview of guideline recommendations

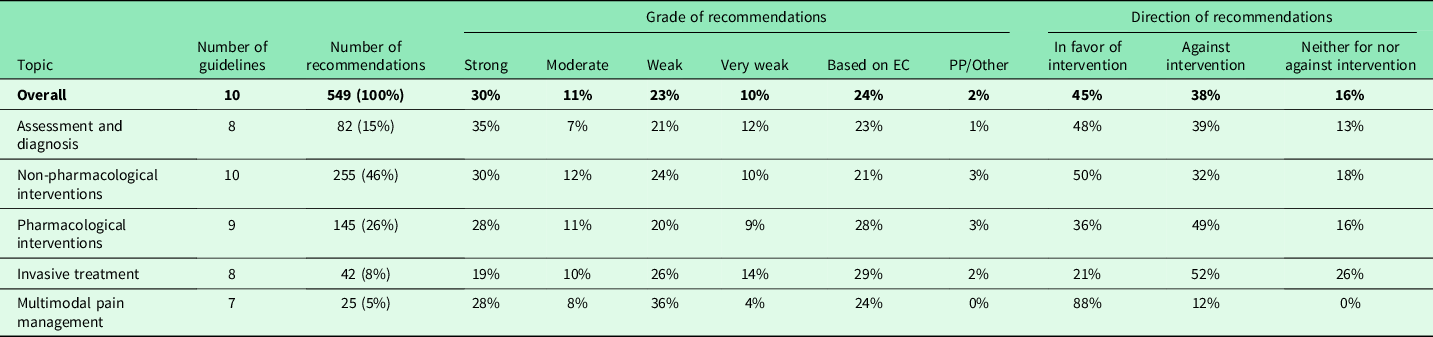

From the 10 included guidelines, we identified 549 recommendations of relevance to diagnosis and management of non-specific LBP in primary care. We assigned all extracted recommendations to one of five topics: assessment and diagnosis, non-pharmacological interventions, pharmacological interventions, invasive treatments and multimodal pain management. The majority of recommendations (46%) coming from all 10 guidelines referred to non-pharmacological interventions, the fewest (5% from 7 guidelines) to multimodal pain management.

The proportion of recommendations associated with the highest level of recommendation was 30%. The proportion of recommendations associated with low levels of recommendation or based on expert consensus was 57%. In total, 11% of recommendations were moderately strong.

Of all recommendations, 45% were in favor of the implementation of the respective interventions and 38% were recommendations against an intervention. Recommendations neither for nor against an intervention were given in 16%. Recommendations for non-pharmacological and invasive interventions showed the highest proportion of recommendations against the implementation of the respective intervention with 49% and 52%, respectively. The lowest proportion of recommendations against interventions (12%) was for multimodal pain management.

For a summary and comparison of the strength and direction of all recommendations categorized by topic, see Table 3.

Table 3. Summary and comparison of the strength and direction of all identified recommendations categorized by topic

EC = expert consensus; PP = practice point.

Assessment and diagnosis

Eight of 10 guidelines (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; KCE, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020) presented recommendations relevant to this topic. The recommendations mainly addressed the physical examination and medical history, diagnostic assessment by imaging and the assessment of psychosocial and workplace factors, the latter two mainly concerning the risk of pain chronicity.

While the majority of recommendations agreed, we also found some contradictory recommendations from different guidelines. In individuals with acute LBP without the presence of red flags, six guidelines (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; KCE, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; ICSI, 2018) recommended strongly against any further diagnostic imaging. In contrast, the most recent guideline indicated that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for or against obtaining imaging (NASS, 2020). The authors of this guideline cite an RCT from 2002 as the basis for their recommendation. In contrast, the authors of the NVL, for example, base their recommendation on the results of a systematic review from 2009.

Recommendations concerning specific investigation procedures for diagnosing LBP (X-ray, magnet resonance imaging, computed tomography, myelography, bone scanning, single-photon emission computed tomography, electromyography, ultrasound, fluoroscopy, videofluoroscopy, discography, myeloscopy) were given only in two guidelines published in the US (ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020). For them, we did not identify any discordant recommendations.

Non-pharmacological interventions

All 10 guidelines (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; ACP et al., Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea2017; KCE, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020) included recommendations on non-pharmacological intervention, which account for nearly 50% of all relevant recommendations. The topics of non-pharmacological interventions mainly cover areas such as physical activity, patient education, psychosocial interventions, manual therapies, alternative treatments and medical devices. The latter areas in particular provide recommendations for a variety of specific interventions. For this topic, 30% of recommendations were graded as strong.

In general, non-pharmacological interventions with or without additional pharmacological therapy were consistently recommended in all guidelines as a first-line intervention for non-specific LBP. However, there were some inconsistent recommendations between the guidelines in terms of the specific interventions, especially the use of different medical devices. Three to four guidelines, explicitly recommend against the use of laser therapy (NVL, 2017; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020), therapeutic ultrasound (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; KCE, 2017; NASS, 2020), interferential therapy (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; KCE, 2017) or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; KCE, 2017) for managing chronic LPB. In contrary, according to one European guideline (BMASK, 2018), all these interventions can be used in the course of treatment of chronic LPB. Furthermore, self-applications of cryotherapies are recommended in the US guidelines (ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019), while two European guidelines (NVL, 2017; BMASK, 2018) stated that cold therapy should not be used.

Pharmacological interventions

In total, 26% of all relevant recommendations, from 9 out of 10 guidelines, addressed the topic of pharmacologic treatment of LBP. Interventions for which we found the majority of recommendations included pain medication (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol, opioids and others), muscle relaxants, steroids, antidepressants, antiepileptic medication and others (eg, vitamins and supplements). On one hand, recommendations addressed the topic in a generalized way and on the other hand dealt with specific interventions. Often these were recommendations that advised against an intervention (49%).

The vast majority of recommendations were in agreement and only a small number of contradictory recommendations consisted of different guidelines. However, these also concerned the use of antidepressants for the treatment of LBP. While three guidelines (NICE, 2016; NVL, 2017; NASS, 2020) recommended against the use of antidepressants, two guidelines (VA/DoD, 2017; ACOEM, 2019) actually recommended the use of certain antidepressants and two further guidelines stated that the use of antidepressants was possible in certain situations (KCE, 2017; BMASK, 2018). We also found some disagreement between recommendations concerning the use of paracetamol, antiepileptic medications and the intravenous administration of drugs.

Invasive treatments

Recommendations concerning invasive treatments such as surgical procedures, spinal injections, intradiscal steroid injections and sacroiliac or facet joint injections, trigger point injections, radiofrequency denervation and spinal cord stimulation were made in eight guidelines (NICE, 2016; KCE, 2017; NVL, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; ICSI, 2018; ACOEM, 2019; NASS, 2020).

Most guidelines recommended against an invasive therapy option to treat non-specific LBP or made no recommendation for or against the use of an intervention (26%). However, we identified some discrepancies in the recommendations, for example two European guidelines (NICE, 2016; KCE, 2017) recommended the use of radiofrequency denervation for management of chronic LBP, while one US guideline (ACOEM, 2019) recommended against the use and another US guideline (VA/DoD, 2017) stated inconclusive evidence to recommend for or against this intervention. Other minor discrepancies concerned the use of trigger point or facet joint injections and spinal cord stimulation.

Multimodal pain management

Multimodal pain management (including multidisciplinary programs based on a biopsychosocial approach) for the management of chronic LBP was addressed in 7 out of 10 guidelines (NICE, 2016; KCE, 2017; NVL, 2017; VA/DoD, 2017; BMASK, 2018; CCGI, Reference Bussieres, Stewart, Al-Zoubi, Decina, Descarreaux, Haskett, Hincapie, Page, Passmore, Srbely, Stupar, Weisberg and Ornelas2018; ACOEM, 2019).

Recommendations for this topic account to only 5% of all relevant recommendations and are, moreover, mostly general. We did not identify any discordant recommendations. The proportion of recommendations in favor of these intervention (‘DO’) was high (88%), but only few recommendations were graded as strong (28%).

Discussion

Our research resulted in 10 relevant guidelines of sufficient methodological quality. Recommendations from these guidelines addressed largely all topics relevant to the management of LBP in primary care and included the topics assessment and diagnosis, non-pharmacological treatment, pharmacological treatment, invasive treatment and multimodal pain management. While about a third of the recommendations were strong recommendations, about half of the recommendations were associated with only low or very low grades of recommendations. A high proportion of recommendations advised against certain interventions. The recommendations from the different guidelines, in particular, the more general recommendations on diagnosis and therapy strategy, were largely in good agreement. Only a small number of contradictory recommendations consisted of different guidelines. Mostly these recommendations dealt with very specific interventions, for example different medical devices. However, they also concerned important topics like diagnostic imaging for acute back pain or the use of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of LBP.

One possible reason for conflicting recommendations is the different assessment of the underlying evidence. For example, both the ACOEM 2019 and the NICE 2016 guidelines base their respective recommendations for and against the use of duloxetine in the treatment of chronic LBP on the same three RCTs (Skljarevski et al., Reference Skljarevski, Ossanna, Liu-Seifert, Zhang, Chappell, Iyengar, Detke and Backonja2009; Skljarevski et al., Reference Skljarevski, Zhang, Chappell, Walker, Murray and Backonja2010a; Reference Skljarevski, Zhang, Desaiah, Alaka, Palacios, Miazgowski and Patrick2010b). However, NICE judged the risk of bias in these studies to be high. Authors of guidelines can also derive a recommendation against the respective intervention from insufficient evidence or determine that a recommendation for or against the intervention is not possible. Discrepancies in recommendations may also result from different methods of evidence selection and varying interests among guideline development groups, differing health care systems and differences between countries.

What was noticeable about all the guidelines was that they contained a large number of recommendations against the implementation of interventions. One reason for this is that unnecessary or even harmful interventions are often used in the treatment of people with LBP (Mafi et al., Reference Mafi, McCarthy, Davis and Landon2013; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Downie, Maher, Moloney, Magnussen and Hancock2018), and the guideline authors want to prevent this (eg, the use of opioids for pain management or imaging tests in the assessment of acute LBP). However, negative recommendations also seem to reflect an insufficient or inconclusive evidence base.

We identified one other current overview on the topic of guideline recommendations for the management of people with LBP (Oliveira et al., Reference Oliveira, Maher, Pinto, Traeger, Lin, Chenot, van Tulder and Koes2018). In contrast to our study, this review also included guidelines from non-WHO ‘Stratum A’ countries (Africa, Brazil, Malaysia, Mexico and the Philippines) but limited the number of guidelines to one per country. While we used a validated tool (AGREE II) to assess the quality of the guidelines included, this was not the case in the review by Oliveira. No analysis of the proportion of recommendations in each level of recommendation category or the proportion of recommendations for or against intervention was carried out. Oliveira et al. found disagreement between recommendations from different guidelines concerning the use of paracetamol, herbal medicine, muscle relaxants, acupuncture and spinal manipulation. No analyses on the proportion of disagreeing recommendations were carried out.

Our overview has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the most current review on the subject with the last search carried out in September 2020. In addition, we only included evidence-based guidelines, thus minimizing the risk of bias. We thoroughly assessed the methodological quality of the included guidelines with the AGREE II instrument. By analyzing the topics on which guidelines give recommendations, the corresponding grades of recommendations and discrepancies, we provide an overview of current guideline recommendations on which a clinical pathway can be based. Our overview also highlights the fact that even with evidence-based guidelines there are still important differences in the overall quality of the guidelines, the consideration of risk of bias in the underlying evidence and therefore in the trustworthiness of the respective recommendations.

Limitations of this study were the exclusion of guidelines that were not published in English or German and the restriction to guidelines from high-income WHO ‘Stratum A’ countries. This approach was chosen because LBP is a particular problem in industrialized countries (Hoy et al., Reference Hoy, Bain, Williams, March, Brooks, Blyth, Woolf, Vos and Buchbinder2012) and we therefore considered guidelines from nations in which back pain plays a relatively minor role within the health care system to be of lesser relevance. Another reason for the restriction to stratum A countries is that it can be assumed that the medical services available are comparable to those in the Austrian health system.

Further research should carry out in-depth analyses of the reasons for discrepancies in recommendations (both in terms of recommendations to the contrary and of varying degrees of recommendation). Why do guidelines, which have all carried out systematic searches as indicated in the methodology, nevertheless use different literature for their evidence base? Why guidelines arrive at different recommendations based on the same evidence? Similar reviews and analyses should also be carried out on guidelines for other diseases. Results can then inform the development of methodologically high-quality guidelines with reliable recommendations and identify research needs in terms of the evidence base for interventions. There is also need for research on the development of structured clinical pathways based on such guidelines.

Conclusion

Current evidence-based guidelines published in stratum A countries provide recommendations for all major aspects of the management of people with LBP in primary care. However about 50% of these recommendations are weak or very weak. The majority of available recommendations addressed non-pharmacological interventions. In total, 38% of recommendations were Do not recommendations, advising against an intervention. Recommendations from different guidelines were largely consistent, but we found some disagreeing recommendations mostly for specific interventions. However, they also concerned important topics like diagnostic imaging for acute back pain or the use of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of LBP.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000626

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Phillip Elliott for editing the manuscript.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions (http://www.hauptverband.at). This manuscript is based on the report “Behandlungspfad: Nicht-spezifischer Rückenschmerz auf Primärversorgungsebene”.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Author’s Contribution

C.Z., K.J. and T.S. searched the literature. C.K. and T.S. assessed the quality of the guidelines. C.K. and C.Z. extracted and synthesized the data. Synthesis of the data was amended by K.H. and T.S. The manuscript was drafted by C.K. and T.S. All authors revised drafts of the manuscripts and approved the final version.