Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is a symptomatically defined condition characterised by a minimum of six months severe physical and mental fatigue of new onset which cannot be explained by other medical causes (Fukuda et al., Reference Fukuda, Strauss, Hickie, Sharpe, Dobbins, Komaroff, Schluederberg, Jones, Lloyd, Wessely, Gantz, Holmes, Buchwald, Abbey, Rest, Levy, Jolson, Peterson, Vercoulen, Tirelli, Evengard, Natelson, Steele, Reyes and Reeves1994). Functional impairment is substantial and a number of other physical, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric symptoms may be present (CFS/ME WG, 2002). Prevalence estimates vary but the Joint Working Group’s 2002 report to the UK’s Chief Medical Officer (CFS/ME WG, 2002) suggests a population prevalence of at least 0.2–0.4% in the United Kingdom. The condition is associated with high levels of disability and healthcare use (McCrone et al., Reference McCrone, Darbishire, Ridsdale and Seed2003). The annual economic impact of CFS in the United States is estimated to be $9.1 billion in lost productivity, not including medical costs or disability payments. The average family affected by CFS/ME loses $20 000 a year in wages and earnings (Fukuda et al., Reference Fukuda, Strauss, Hickie, Sharpe, Dobbins, Komaroff, Schluederberg, Jones, Lloyd, Wessely, Gantz, Holmes, Buchwald, Abbey, Rest, Levy, Jolson, Peterson, Vercoulen, Tirelli, Evengard, Natelson, Steele, Reyes and Reeves1994). The prognosis of CFS/ME is variable and it is suggested that only a small minority of patients recover to previous levels of health or functioning (CFS/ME WG, 2002).

A number of different approaches to the management of CFS/ME are used in clinical settings including cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), graded exercise therapy (GET), and counselling (Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Hawton, Simkin, Surawy, Hackmann, Klimes, Peto, Warrell and Seagroatt1996; Whiting et al., Reference Whiting, Bagnall, Sowden, Cornell, Mulrow and Ramirez2001; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Bagnall, Hempel and Forbes2006; Price et al., Reference Price, Mitchell, Tidy and Hunot2008). Guidelines for treatment provided by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom (2007) suggest that CBT and GET, delivered by specialist therapists, show the clearest evidence of benefit from the available published research.

NICE guidelines advocate a prominent role for primary care and suggests that healthcare professionals should aim to establish a supportive and collaborative relationship, working in partnership with the adult or child with CFS/ME, family, and carers to facilitate their effective management. The guidelines emphasise the importance of a definitive diagnosis and suggest that referral to a specialist should be made on the basis of the person’s needs and symptoms: within six months of presentation to those with mild symptoms, within three to four months to those with moderate symptoms, and immediately to those with severe symptoms.

In 2004, following on from the report to the Chief Medical officer (CFS/ME WG, 2002) the UK Department of Health established a number of local clinical network coordinating centres to support and develop the work of specialist services and local multi-disciplinary teams engaged in the treatment and management of CFS/ME across the country. There are now 13 centres, which provide a range of services including, in some centres, CBT and GET, although there are regional variations in the availability of these treatments and referral practices of general practitioners (GPs) to the services (CFS/ME Service Investment Programme Report, 2004–2006).

Previous literature outlines the negative views and scepticism that GPs express towards people with CFS/ME (Åsbring and Närvänen, Reference Åsbring and Närvänen2003; Raine et al., Reference Raine, Carter, Sensky and Black2004). In addition, sufferers have been shown to be dissatisfied with the medical care they receive (Ax et al., Reference Ax, Gregg and Jones1997) and an adversarial nature to medical consultations has been described (Cooper, Reference Cooper1997). Our previous work suggests that GPs find making the diagnosis of CFS/ME difficult (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Dowrick, Wearden, Richardson and Peters2010) and this at least partly relates to uncertainty over the nature of the condition; it seems that GPs may not have a useful explanatory model about CFS/ME and that the model may vary between GPs and may, indeed, shift in the course of a GP’s career (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Cahill, Dowrick, Wearden and Peters2008). If the GP does not have a model he/she feels comfortable with, then discussing the diagnosis of CFS/ME with a patient may become problematic (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Cahill, Dowrick, Wearden and Peters2008). This may result in difficulties in agreeing the nature of the illness with the patient and negotiating appropriate referral for further management (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Dowrick, Wearden, Richardson and Peters2010).

There is considerable evidence that when people experience a threat to their health such as symptoms or chronic illness, they are motivated to form an understanding or personal model of that threat, to guide their attempts to neutralise the threat, that is to get well (Leventhal et al., Reference Leventhal, Nerenz and Steele1984). In the case of CFS/ME, where there is no medical explanation for fatigue and often no treatment advice forthcoming, patients struggle to make sense of their illness, and may develop models of their illness in which fluctuating symptoms are interpreted as evidence of bodily damage or relapse (Deary et al., Reference Deary, Chalder and Sharpe2007). Cognitive behavioural approaches to CFS/ME may help patients consider whether their personal model of their illness is helpful for them in their attempts to become well.

Pragmatic rehabilitation (PR) is a therapist-facilitated self-management intervention for CFS/ME, which shares features in common with CBT and GET, but which does not require a specialist CBT or physiotherapist to deliver it. PR conceptualises the symptoms experienced by people with CFS/ME as a consequence of physiological dysregulation, including cardiovascular and muscular deconditioning and disruption of sleep–wake cycles. PR differs from conventional CBT in that the treatment starts with an explicit presentation of the PR explanatory model for CFS/ME, supported by a referenced manual. Treatment involves a graded activity schedule carefully monitored to be well within the patient’s abilities, with gradual increments, regularisation of sleep, and the collaborative development of plans working towards rehabilitation (Wearden and Chew-Graham, Reference Wearden and Chew-Graham2006). There is evidence that PR is effective in secondary care (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Bentall, Nye and Edwards2001) and a recent trial (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Riste, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Dunn, Richardson, Lovell and Powell2006) suggests that PR is effective for some patients in primary care, but the effect is not sustained (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Riste, Richardson, Lovell and Dunn2010). Moss-Morris and Hamilton (Reference Moss-Morris and Hamilton2010) suggest that more work is needed to determine for whom PR works best and the factors that make it an acceptable treatment to people with CFS/ME.

This qualitative study aimed to establish the factors which are important for patients to engage in this novel intervention for CFS/ME within a trial (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Riste, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Dunn, Richardson, Lovell and Powell2006; Reference Wearden, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Riste, Richardson, Lovell and Dunn2010) and to extrapolate the findings to make recommendations for the referral process to such a service, were it to be commissioned.

Methods

The sample was drawn from patients participating in a randomised controlled trial of two nurse-led interventions for CFS/ME in primary care: the FINE trial (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Riste, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Dunn, Richardson, Lovell and Powell2006). Patients were recruited from 44 primary care trusts in the North West of England into the trial. Practices were contacted and GPs invited to refer registered patients with CFS/ME to the trial. Patients were considered eligible if they were aged 18 or above, fulfilled the Oxford inclusion criteria for CFS/ME, scored 70% or less on the SF-36 physical functioning scale (Ware and Sherbourne, Reference Ware and Sherbourne1992) and scored four or more on the 11-item Chalder fatigue scale (Chalder et al., Reference Chalder, Berelowitz, Pawlikowska, Watts, Wessely, Wright and Wallace1993). Following consent, eligible patients were randomised to one of the three arms: PR, supportive listening (SL), or treatment as usual. Full details of the interventions and trial recruitment procedures are provided elsewhere (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Riste, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Dunn, Richardson, Lovell and Powell2006).

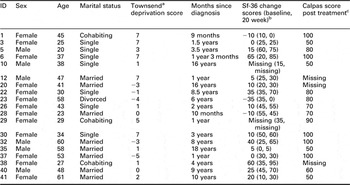

Sampling for this qualitative study was purposive. A total of 42 patients were interviewed following the completion of the 18-week intervention, of which 19 had been in the PR arm of the trial. Table 1 outlines details of the participants in the study reported here. Sampling was purposive to achieve mix of gender, age, postcode, and duration of illness (time since diagnosis), SF36 post-treatment and CALPAS scores. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between November 2005 and March 2008. Respondents were interviewed by members of the research team in their own homes. Interview guides provided a flexible framework for questioning and explored a number of areas including patients’ views on the treatment intervention. The interviewer used a combination of open questions to elicit free responses, and focused questions for probing and prompting. Interviews lasted between about 30 and 90 minutes. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Table 1 Participant details

aTownsend P, Philmore P, Beattie A. Health Deprivation: Inequality and the North. London: Croom Helm; 1988.

bScores range from 0 (lowest functioning) to 100 (highest functioning). Change scores 20 week – baseline.

cScores for response to question ‘does the type of treatment you are receiving match your ideas about what helps people with your illness?’ Scores range from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much).

Analysis proceeded in parallel with the interviews and was inductive. Coding was informed by the accumulating data and continuing thematic analysis (Malterud, Reference Malterud2001). Transcripts were read and discussed by researchers from different professional backgrounds: primary care and psychology (Henwood and Pidgeon, Reference Henwood and Pidgeon1992). Thematic categories were identified in initial interviews which were then tested or explored in subsequent interviews where disconfirmatory evidence was sought (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Interpretation and coding of the data were undertaken by all the authors and the themes were agreed upon through discussion. An overall set of master themes was identified and a comprehensive corpus of extracts supporting each theme produced.

The narrative account reported below focuses on the factors that influence engagement in the PR intervention from the perspective of patients. This analysis aimed to identify the meaning of the experiences being reported, particularly with respect to the experiences within the patient-trial nurse encounter. Data reporting other aspects of this study are reported elsewhere (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Cahill, Dowrick, Wearden and Peters2008; Peters et al., in preparation). In reporting the final analysis, data are presented from transcripts of interviews of participants who had been in the PR arm of the trial, to illustrate the range and commonality of meaning of each category of analysis. Although qualitative analysis of this type is inevitably subjective, extracts allow the reader to make their own assessments of the interpretations made. The wide use of verbatim extracts is intended to attest to the credibility of the final account.

Results

Three factors emerged as key in the analysis: i) feeling accepted and believed by the therapist, ii) own acceptance of the diagnosis, and iii) accepting model of illness presented by the therapist.

Feeling accepted by the therapist

For many patients, their belief that they were fully understood by the nurse therapist both personally and in terms of their illness condition was emphasised. Talking to someone who listened and understood was described by a number of patients as the most positive part of the treatment intervention:

It was just an understanding from her that I didn’t, haven’t had from anybody else.

(P30)

For those patients who described feeling understood by the therapist, this was described as a novel experience and in stark contrast to the disbelief and scepticism encountered elsewhere in their encounters with health professionals. Patients often attributed this to the invisibility of the condition:

somebody sitting there saying to you, I know what you are going through and I have got other people who are going through the same thing, and if you look up this booklet, that’s exactly you know, you can describe yourself in a booklet and before, I had never really been able to pinpoint myself, or box myself, to anywhere particular.

(P28)

Being believed and feeling understood by the therapist emerged as key factors in the formation of a positive relationship. Trial nurses were described in glowing terms both personally and in terms of their professional expertise:

She was a cracker, I couldn’t fault her.

(P32)

Well she was very encouraging all along and I was very impressed with her whole attitude.

(P10)

However, being heard and understood seemed to be of greater value than the professional medical knowledge attributed to the therapist:

At the actual end of it (treatment), I felt like I had lost somebody really … I mean you can talk to some people, can’t you and obviously I could talk to her because she understood. A lot of people don’t understand. She would listen to me and explain things and we were on the correct level.

(P37)

The nurse therapist’s understanding of the patient was evidenced for some by her perceived ability to manage their condition flexibly within the treatment protocol and to bring a fresh outside perspective to problems which had appeared insurmountable before.

I think the understanding and listening by [Nurse C]. She understood what my problems were, and she listened to them. Told me how to get round the different ones, how to sort of beat the little buggers you know, beat the little nasties, that was ruining my life.

(P32)

The extent to which the patient perceived the nurse therapist, believed in their problems, and understood them in a wider context was an important factor in determining whether the patients continued to engage with the therapy and found the intervention offered acceptable.

Own acceptance of diagnosis

Some patients described the treatment intervention offered as having been especially helpful in terms of their accepting the diagnosis. Having some explanation for and a greater understanding of their symptoms were described as fundamentals in accepting the condition:

I hadn’t really accepted my illness when she first came to visit me.

(P28)

I thought maybe she could give me some information, you know, in order I suppose really for me to actually believe that it was ME. For me myself to believe it was ME, not other people, because remember, I started myself not believing it was ME, because I was as ignorant as other people about it, because I knew nothing you know.

(P6)

Thus, engaging with the therapy was dependent upon the patient accepting what their symptoms represented and the diagnostic that was applied. Some patients described their interactions with the nurse therapist as validating the illness, and the diagnosis, convincing them as to the reality and seriousness of their condition. Patients described how their struggle to find an acceptable and satisfactory model for the symptoms they experienced was frightening. These patients thought that if they could not explain their symptoms to themselves in terms of physiological or physical processes, the symptoms must have a ‘psychological’ origin. Therfore, patients were buying into the physical versus mental illness divide, and not liking the conclusion that they might have a mental problem:

If I had a broken leg they could physically see it, but many with chronic fatigue, there’s nothing really visible.

(P3)

The increased knowledge about their symptoms through the information provided (by the therapist and in the manual) within the intervention was described as reassuring:

At the beginning it was embarrassing, because I didn’t know that was part of the symptoms, I actually thought at one point I was like cracking up.

(P1)

You don’t feel so alone in the fact that you know, that your symptoms are there, and that other people have these symptoms. Like I say what I got off [Nurse A] was because she had met with people and seen people who felt as I did. And when she mentioned things and I thought oh yes, that’s right, and I am, so I am not going round the twist.

(P25)

Accepting their condition and diagnosis was described as being necessary to allow progress with treatment:

It’s the acceptance of what is wrong with me, if you don’t accept it you can’t progress with it.

(P30)

Accepting their diagnosis was also key for some patients in terms of absolving them from guilt they felt about their reduced ability to perform activities and functioned as a means of enabling patients to feel they had permission to do less, leading to better control and management of their symptoms.

I think I sort of denied there was anything wrong with me, so I kept pushing on when I knew that after I had done so much I would crash, and it was seeing Nurse B that gave me an understanding that I have to take a step back and slow down … I have learnt to not punish myself.

(P30)

Thus, acceptance of the label of CFS, either before referral into the trial, or through discussion of the therapy offered (by the nurse therapist and the trial treatment manual), enabled the patient to believe that the intervention might be appropriate for them.

Acceptance of the model

The third factor that emerged as key in engagement in the intervention was acceptance of the model of the condition (CFS/ME) implied by the treatment offered. Whether or not patients perceived the nurse therapist as having a model of the illness, which matched with their own was vitally important. If the model presented either provided no challenge to, or matched, the patient’s existing illness model, then the treatment intervention helped them formulate their existing model in clearer terms:

A lot of this seemed sort of common sense really like not sleeping in the daytime and stuff but I don’t know, having someone discuss it with me did make me more aware of it I think.

(P5)

Other patients described the treatment intervention as providing a model for their condition where there had been none previously. There were frequent descriptions of how the treatment intervention had resulted in patients’ better understanding of the condition.

She explained all about CFS and the physiology of it really, which was the first time really that I understood why my energy was so low, so that made a lot of sense.

(P38)

Where patients adopted the model presented in the intervention, their reasoning for doing so was based on the extent to which the model presented was resonant with their own experience of the illness and the extent to which the patient perceived the model as making sense:

It hit me, because everything that went in there, it was amazing, it was like, This is Your Life … Everything she said, in those paragraphs, [in the patient manual] was regarding my illness.

(P32)

When patients rejected the rationale for the treatment offered, there were a number of reasons given for this. Some patients held models of the illness before treatment, which were contradictory to that being presented by the nurse therapist and remained unconvinced by the PR model and the rationale for the treatment intervention that it provides.

What I have got is not just a reconditioning problem, I have got something where there is damage and a complete lack of strength actually getting into the muscles and you can’t work with what you haven’t got in terms of energy.

(P10)

I think my main reason is the fundamental theory behind it [the treatment model offered] just disregards it as illness.

(P3)

Some patients regarded the treatment intervention as unsuitable for them because they perceived their condition as being individual and unique and, importantly, not amenable to treatment. These patients described themselves as experts in their own condition, and did not feel that there was anything new they could usefully learn about the condition.

But the other thing that upsets me about that is that when the nurse came round and explained the theory to me, it was sold to me as fact, this is what is happening, there was no element of this is actually quite a contentious issue, I have done some research since and found evidence supporting both camps and there was no part of that session that said there are some people that don’t believe this.

(P3)

Well I am like 17 years on so I have already learnt I have to get on with it and live with it really.

(P20)

Several patients held a model of the illness, which implied that activity was potentially damaging, so patients were fearful of relapse.

Well the sections here [in the manual], I have marked them, like the section here that I didn’t really agree with and I tried to tell her that I didn’t agree, erm, like it says there is no hidden disease, I think there could be something that they haven’t found you know. But activity/exercise cannot harm you, I think it can harm you, if you are not good and you really, really push yourself you can relapse, definitely. And I did try to tell her that, but I think she was, rigid to the book and she thought that was exact, I didn’t.

(P20)

In addition, patients who could not work the management plan into their everyday life felt that it was not a workable model:

Well it sounded logical. But applying it, I think you needed not to have anything else going on in your life, particularly out of the ordinary, to be able to apply it properly and really stick to it.

(P23)

It is unworkable in my opinion. From, I mean I went into this feeling very positive, feeling that I understood the theory, and feeling that it made sense and its something that I wanted to work for me and it was good for me because it made me think right I can take this into my own hands, I can make myself better, but I don’t believe the fundamentals are right and you know, one of the most documented things about this illness is the delayed effect of activity and you know that is quite a basic principle and so is the principle of resting for 10 minutes and then you know you are within your limits and they don’t go together at all.

(P3)

Thus, we suggest that a patient needs to feel that they are believed and understood by the therapist before engaging in the treatment offered. Engagement can help the patient accept their own illness and formulate an adequate explanation for the symptoms experienced. If the patient’s model of illness, either pre-existing or so formulated, is in agreement with that of the therapist, the patient feels further reassured that the therapist has a real and genuine understanding of them and their condition and thus continues to engage in the treatment. Similarly, where models of treatment match, the patient will engage with the intervention. If, however, there is no matching of the patient’s model of the cause of their symptoms of the model of treatment offered, engagement and working with the intervention offered is unlikely.

Discussion

Summary of results

This paper draws together data from interviews with CFS/ME patients following their participation in a primary care trial nurse therapist delivered interventions for CFS/ME and identifies the factors described by the patients as key in influencing their level of engagement with one of these interventions, PR. This intervention was effective in the short-term, but the effect was not sustained (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Riste, Richardson, Lovell and Dunn2010). The factors that seem to be important in engagement with the therapy are ensuring that the patient feels accepted and believed, that the patient accepts the diagnosis, and that the model of treatment offered to the patient matches the model held by the patient. If the patient holds a clearly incompatible model it is unlikely that the patient will engage with, and successfully complete, therapy. A number of respondents rejected the inflexibility of the presentation of the model, and this may be due to the intervention being presented within a randomised controlled trial, and may be less of an issue in development of a service based on this model of intervention, where more flexibility could be offered.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Data are presented from interviews with patients who had received PR, a novel intervention as part of a randomised controlled trial, and thus the views are not necessarily generalisable to all patients with CFS/ME. In addition, all patients interviewed could have been said to have engaged to a certain extent as they had completed the intervention. Patients who had not entered or engaged in the study were not interviewed. Patients were recruited to the trial, however, from primary care across a wide geographical area (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Riste, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Dunn, Richardson, Lovell and Powell2006), and drawn from suburban, rural, and inner city areas (see Table 1). In addition, sampling was purposive to achieve mix of gender, age, postcode, and duration of illness (time since diagnosis), SF36 post-treatment and CALPAS scores. This purposive sampling enabled us to access a range of views, particularly from participants who had not improved (according to SF36) or were less engaged (according to CALPAS). Using authors from different professional and academic backgrounds is a recognised technique for increasing the trustworthiness of the analysis (Henwood and Pidgeon, Reference Henwood and Pidgeon1992).

Comparison with previous literature

Our findings suggest that for treatment interventions to be successful in engaging people with CFS/ME, a number of points must be addressed. It is vital that the patient is believed. A recent systematic review of the expressed needs of people with CFS/ME suggests that patients need to first make sense of their symptoms and gain a diagnosis, and desire recognition of their needs, and respect and empathy from their service providers (Drachler et al., Reference Drachler, Leite, Hooper, Hong, Pheby, Nacul, Lacerda, Campion, Killet, McArthur and Poland2009). Our study confirms this. The scepticism displayed by some GPs about CFS/ME (Åsbring and Närvänen, Reference Åsbring and Närvänen2003; Raine et al., Reference Raine, Carter, Sensky and Black2004) may be because they do not have a satisfactory model of the condition which convinces them of its reality as an illness and provides a potential rationale for management. Patients may be aware of the controversial nature of CFS/ME, and therefore particularly sensitive to being disbelieved, so may put their energies into convincing their doctors that their symptoms are real (Horton-Salway, Reference Horton-Salway2001). If patients feel that their doctors do not really believe that they are ill, especially in the context of past lack of medical support or understanding, the patient–doctor relationship is likely to be undermined, and the patient may be left with a feeling of having nowhere to go (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Cahill, Dowrick, Wearden and Peters2008).

An important aspect of the process of engaging patients and forming a therapeutic alliance with them is the development of an agreed model of the patients’ problems, which provides the rationale for shared, collaborative goals for treatment. We know from other conditions that when patients and their doctors share an explanatory model, patients are more satisfied with their treatment (Callan and Littlewood, Reference Callan and Littlewood1998). Furthermore, there is some evidence that when treatment is in accordance with patients beliefs about depression, they are more likely to engage in it (Elkin et al., Reference Elkin, Yamaguchi, Arnkoff, Glass, Sotsky and Krupnick1999). Previous work with the pragmatic rehabilition model has shown that it can be very effective in helping patients to get better (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Bentall, Nye and Edwards2001), but this study suggests that if the model is not believed by patients, it is less effective (Wearden et al., Reference Wearden, Dowrick, Chew-Graham, Bentall, Morriss, Peters, Riste, Richardson, Lovell and Dunn2010). Our data suggest that for those patients who were struggling to develop a coherent model of their own, or who had a personal model which was unacceptable or unsatisfactory to them, the simple provision of the PR model could be immensely helpful. But for those patients who had a firmly held pre-existing model of CFS/ME, the mere exposure to an alternative formulation was unlikely to result in the acceptance of the new model in the absence of therapeutic work to convince them of its utility or ‘socialise’ them to that model (Roos and Wearden, Reference Roos and Wearden2009). In accordance with Leventhal’s model (Leventhal et al., Reference Leventhal, Nerenz and Steele1984), one factor that is likely to influence the acceptability of an externally provided model is the extent to which it resonates with patients’ own personal symptom experiences.

In our analysis, we distinguished between the themes of ‘feeling believed’ and ‘accepting the diagnostic label’. ‘Feeling believed’ refers to the patient’s sense of being really understood and accepted by the therapist, not just in terms of the symptoms experience but also in more general terms. The invisibility of the condition allied with its chronicity may mean that patients have, before treatment, encountered scepticism from outsiders, with even the concern of those initially sympathetic wearing thin over time. ‘Feeling believed’ refers to the patient’s sense that, through the establishment of a warm and empathetic therapeutic alliance, the therapist really understands them as an individual with their particular symptoms and life circumstances. Our analysis would suggest that it is only at the point at which this is achieved that the patient can begin to examine their own symptoms and condition with a view to ‘accepting the diagnosis’. Although ‘feeling believed’ is likely to involve the patient presenting their story to the therapist and necessitate an appropriate empathetic response from the therapist, accepting the diagnostic label involves a more collaborative approach between the therapist and patient, with the patient accepting the symptoms they are experiencing as real, valid, and a result of having CFS/ME. Faced with ongoing disbelief as to the reality of their illness condition, CFS/ME patients may themselves begin to question the authenticity of their condition, with implications for patients’ self-identity (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Knussen and Flowers2007). Patients who engaged with the intervention described here commented on the novel experience of being fully understood as a very positive and important element of their experience of treatment and highlighted the importance of accepting the condition before progress in treatment was possible. A vital role for the GP is to negotiate and prepare a patient for referral, thus with CFS/ME the GP must believe that the diagnostic label is helpful and that any referral for treatment is potentially valuable. Our previous work (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Cahill, Dowrick, Wearden and Peters2008) suggests that this is not the case.

A further factor influencing the extent to which interventions are perceived as acceptable by patients is the degree to which the models of the illness held by patient and clinician match. The association between beliefs about illness and illness outcomes is well established (Hagger and Orbell, Reference Hagger and Orbell2003) and interventions need to take into account existing beliefs, patient’s past experience and prior ways of managing illness. If the GP does not have a model of illness for CFS/ME, has difficulty or reluctance in making the diagnosis of CFS/ME (Chew-Graham et al., Reference Chew-Graham, Dowrick, Wearden, Richardson and Peters2010) then successful initial management in primary care and appropriate referral will be unlikely.

Clinical implications

This study has important implications, not just for the management of people with CFS/ME, but also for the patients with other medically unexplained symptoms (MUS), or psychological symptoms that are not easily categorised by current diagnostic systems. Given that the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative (Department of Health, 2008) is being proposed as a model for dealing with patients with MUS, these findings are relevant to the referral pathways and treatment models offered.

GPs need to be able to communicate convincingly to patients that their experience is believed and to work with patients to come to an agreed diagnosis before referral is initiated. In addition, GPs need the skills to explore the patient’s illness cognitions to ensure they align with the therapy, otherwise any referral is unlikely to be helpful. For services, the implication is that before any therapy offered, it is important to first elicit a patient’s perceptions and understand the model they hold of their illness.

Acknowledgements

This paper is written by the authors on behalf of the FINE Trial Group: FINE Trial Group consists of: Colette Bennett, Richard Bentall, Laura Booth, Joanna Brooks, Greg Cahill, Anna Chapman, Carolyn Chew-Graham, Susan Connell, Christopher Dowrick, Graham Dunn, Deborah Fleetwood, Laura Ibbotson, Diana Jerman, Karina Lovell, Jane Mann, Richard Morriss, Sarah Peters, Pauline Powell, David Quarmby, Gerry Richardson, Lisa Riste, Alison Wearden, and Jennifer Williams. We are indebted to all the patients who took part in the study and to Greg Cahill who undertook some of the data collection.

Funding

Funding body: Medical Research Council G200212 [ISRCTN 74156610]. *FINE trial: fatigue intervention nurse evaluation – a multi-centred Medical Research Council (MRC) funded randomised control trial. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Competing interests:

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study had been reviewed and approved by the Eastern MREC (reference 03/5/62) and had PCT R&D approval.

Author’s contributions

CCG designed and managed this qualitative study. She contributed to the data collection and analysis and drafted the paper. She is guarantor for the study and paper. JB contributed to recruitment of patients, data collection, and analysis and writing the paper. AW and CD contributed to data analysis and writing the paper. SP designed and managed this qualitative study and contributed to the data collection and analysis and writing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.